Liam Reynolds, Jung Hyun Choi, Vanessa G. Perry

URBAN.ORG

April 22, 2022

(halbergman/Getty Images)

Rapid home price appreciation has built considerable wealth for homeowners, but it has made homeownership less attainable for first-time homebuyers. This concern is especially acute for Black households because the Black-white homeownership gap is as large today as it was before the passage of the Fair Housing Act.

To narrow this gap, fair housing advocates are increasingly calling for the use of special purpose credit programs (SPCPs), which allow lenders to offer credit on favorable terms to borrowers of a protected class who have suffered economic disadvantages. SPCPs reach these borrowers by offering special purpose credit either directly to them (people based) or in places where many of them live (place based).

Because of the continued prevalence of neighborhood racial segregation in many US cities, place-based SPCPscould reduce the racial homeownership gap. But there’s a challenge to this solution: no place is homogenous, so place-based programs that seek to increase Black homeownership will inevitably benefit some borrowers who are not Black and leave out some Black borrowers who are struggling to become homeowners.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) provides useful context. Born out of the civil rights movement, the CRA aims to redress the effects of redlining by encouraging banks to lend in low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods. Despite these goals, Black borrowers in LMI neighborhoods receive a disproportionately small share of home loans.

Similarly, several proposed programs would direct assistance toward historically redlined neighborhoods. But Black people are only the third-largest racial group—behind white and Latinx people—in redlined areas, and those Black residents make up only 8 percent of the total Black population in the US.

Because of considerable variation in these neighborhoods’ demographics, some formerly redlined areas with mostly Black residents may be strong candidates for place-based SPCPs. But nationwide data suggest that targeting allpreviously redlined neighborhoods may not have the disproportionate impact on Black homeownership that proponents hope, especially in cities where Black households are geographically diffuse.

People-based SPCPs may be a more effective way to close the Black-white homeownership gap because they enable lenders to direct a program exclusively toward Black borrowers.

Race-based lending barriers show the value of people-based SPCPs

Despite the structural barriers that make it harder for Black applicants to access mortgage credit than white applicants, many homeownership programs (e.g., Fannie Mae’s HomeReady and Freddie Mac’s Home Possible) are based on income rather than race.

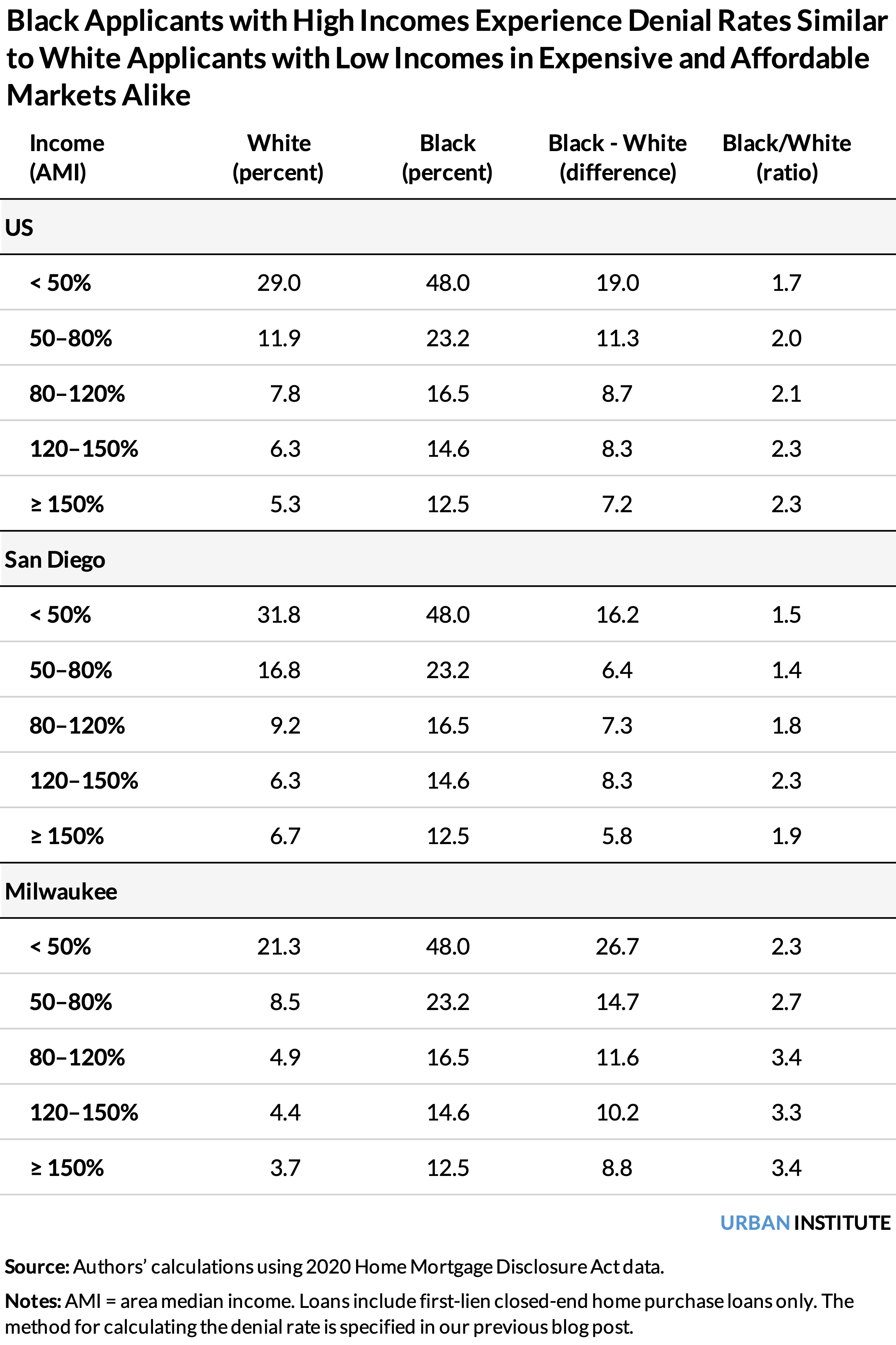

Our analysis of 2020 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data shows Black applicants are more likely to be denied than white applicants at all income levels nationwide. Even Black applicants with incomes above 150 percent of the area median income (AMI) have a higher denial rate than white applicants with incomes between 50 and 80 percent of the AMI. These patterns hold across high- and low-cost markets, though the racial gap is generally smaller in expensive cities—likely because prices are so high that even white households with high incomes have difficulty purchasing homes.

For example, in San Diego, California—one of the most expensive metropolitan areas in the country—Black applicants experienced mortgage loan application denials 1.5 to 2.3 times as often as white applicants, depending on income. Among those with the highest incomes, Black applicants were almost twice as likely as white applicants to be denied.

In Milwaukee, a relatively affordable housing market, the differences are even more stark. Black applicants were between 2.3 and 3.4 times more likely than white applicants to have their applications denied, and the biggest difference is in the highest income group.

These differences in denial rates, even after controlling for income, reflect generations of exploitative practices that have had a lasting impact on wealth and creditworthiness, which justifies race-conscious people-based SPCPs.

How can lenders design people-based SPCPs to narrow the Black-white homeownership gap, and what resources do they need?

- Analyze the denial reasons of their target populations to determine what kind of assistance would most effectively increase access to homeownership.

Because homeownership barriers vary considerably across race and geography, understanding the barriers facing the target population is essential to presenting solutions. Credit history was the most frequently listed denial reason among Black applicants nationally. But in San Diego and Milwaukee, credit history–related denials were only half as common, while debt-to-income ratio and collateral, respectively, were most prevalent.

Understanding these patterns enables lenders to tailor SPCPs to the distinct challenges of the communities they serve. Places that have denial reason profiles like what we observe nationally may benefit most from flexible credit underwriting standards; in communities like San Diego and Milwaukee, down payment assistance could have a larger impact. - Fill data gaps.

Before launching an SPCP, for-profit lenders must show that the borrowers they intend to serve are unlikely to receive credit—or would have to pay more for it—under traditional standards. HMDA data are currently the best publicly available data that lenders can use, as they include information on borrowers, loans, and property characteristics for most mortgage applications annually. But these data have limits.

Some potential buyers aren’t reflected in the data because they may be discouraged from applying for a mortgage in the first place, a trend exacerbated by low supply, increased competition from investors, tight underwriting standards, and pandemic-related financial setbacks. Without information on these potential homebuyers, it is difficult for lenders to know how to address their specific challenges.

Additionally, although credit history is the most common reason for mortgage denial nationally, publicly available HMDA data do not include loan-level credit score data because of privacy concerns. These data are essential in constructing SPCPs to serve consumers who were denied because of their credit score, as near-prime applicants who are almost qualified for a loan will have different needs than subprime applicants who require more assistance.

As such, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau could provide this information at least for small-scale geographies (e.g., census tracts), if not at the loan level. - Increase lenders’ awareness and provide guidance and support.

Many lenders are still unaware of SPCPs. Along with increasing lenders’ awareness, three advances could further facilitate them to initiate SPCPs: (1) a repository of well-documented evidence to support and inform lenders designing SPCPs; (2) greater sharing of examples and best practices, along with clearer guidance from federal regulators; and (3) established securitization pathways via the secondary mortgage market (e.g., the Federal Housing Administration, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac).

The recent interagency statement assures lenders that SPCPs are permissible under the Fair Housing Act. As more lenders initiate SPCPs, we hope to gather more evidence on how these programs can effectively reduce the racial homeownership gap.

The Urban Institute has the evidence to show what it will take to create a society where everyone has a fair shot at achieving their vision of success.

No comments:

Post a Comment