CRT AND PRAXIS

The Ivy League’s Reckoning With Slavery Is Long OverdueHarvard comes clean, but it and others still put self-interest over fairness.

MICHAEL MECHANIC

Senior Editor|

Mother Jones

Mother Jones

APRIL 28, 2022

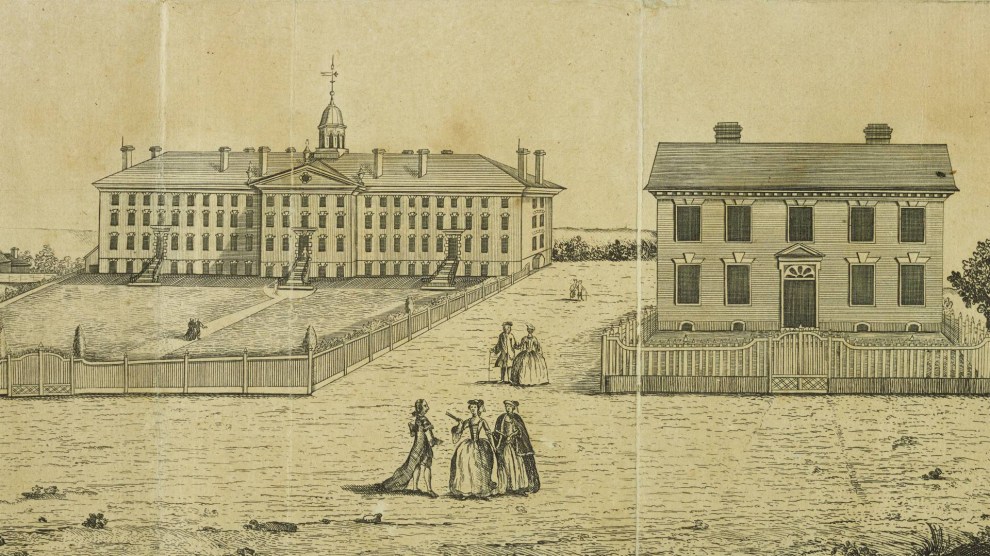

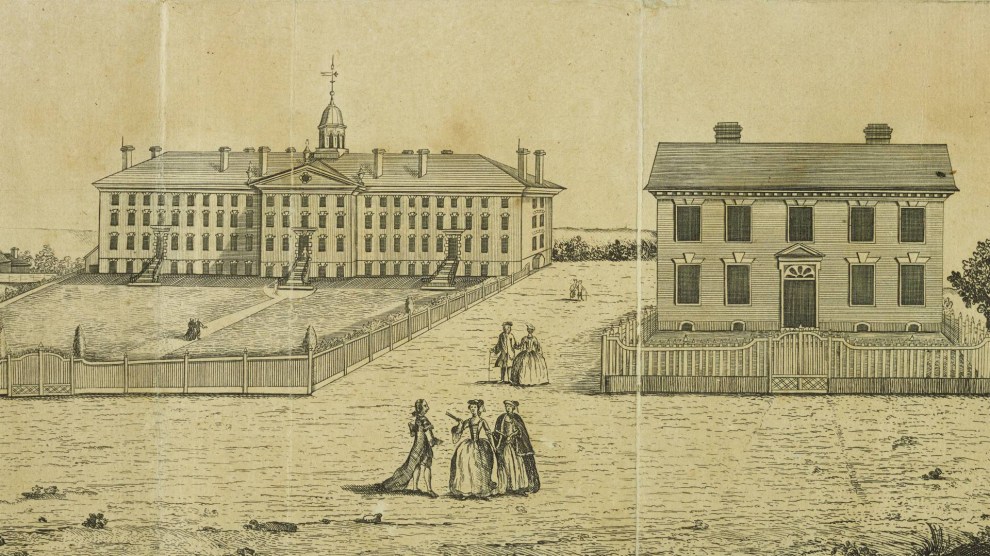

A 1764 engraving of Princeton's Nassau Hall (left) and President’s House, where the enslaved servants of a deceased campus president were to be auctioned off in 1766.

A 1764 engraving of Princeton's Nassau Hall (left) and President’s House, where the enslaved servants of a deceased campus president were to be auctioned off in 1766.

Henry Dawkins/Princeton University Archives

In a report released on Tuesday, Harvard began the process of grappling with its connections to the “peculiar institution” of slavery: “We now officially and publicly—and with a steadfast commitment to truth, and to repair—add Harvard University to the long and growing list of American institutions of higher education, located in both the North and in the South, that are entangled with the history of slavery and its legacies,” the introduction proclaims.

Contrary to the simplistic narratives many American schoolkids are fed, slavery was much more than the foundation of the South’s agrarian economy and the font of its white wealth. Slavery thrived in the North, too, and even when those colonies began to outlaw it, they continued to profit from and fuel demand for the cotton, sugar, and other products that relied on forced human labor. (Clint Smith includes an eye-opening chapter about slavery in New York in his acclaimed recent book, How the Word Is Passed.)

Slavery was integral to Harvard, according to the report. From its 1636 founding until 1783, when Massachusetts deemed slavery unlawful, the college’s leaders, faculty, and staff “enslaved more than 70 individuals,” the report notes. “Enslaved men and women served Harvard presidents and professors and fed and cared for Harvard students.”

Harvard also profited via, “most notably, the beneficence of donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading.”

The university, which is now creating a $100 million restitution fund, also profited indirectly from, “most notably, the beneficence of donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading.”

The report brought to mind a 2017 article about slavery at Princeton University that I came across while researching my own book about the advantages bestowed upon America’s elite. The town of Princeton, where I attended high school in the early ’80s, had a substantial Black population despite its relative affluence and preppie vibe. There was a rumor then, which persists, that Princeton students from slave states used to arrive on campus with their enslaved servants in tow, and then free them upon graduation—hence the thriving local Black community. That rumor is false, as it turns out.

Princeton historians Craig B. Hollander and Martha A. Sandweiss wrote, in the above-mentioned article, that the college formally forbade students from bringing enslaved servants to campus in 1794, yet “we found absolutely no evidence” that they had ever done so, Sandweiss told me in an email. “Closest we found is the well documented story of James Madison, whose enslaved servant basically accompanied him to campus, dropped him off, and headed back home to Virginia.”

The same was not true of the leadership. Hollander and Sandweiss reported that the first nine presidents of the College of New Jersey, as Princeton was then known, were slave owners, or had been at some point. When Princeton’s fifth president, Samuel Finley, died in July 1766, they wrote, his possessions were put up for sale: These included “two Negro women, a Negro man, and three Negro children.” The woman, according to Finley’s executors, “understands all kinds of house work, and the Negro man is well fitted for the business of farming in all its branches.” If they remained unsold, they were to be auctioned off at the president’s campus residence on August 19 of that year.

(Like most universities with direct ties to slavery, Princeton hasn’t set aside money for restitution or reparations, although it and other schools have launched major research projects—Sandweiss directs Princeton’s—to document those connections. The Princeton Theological Seminary, a separate local institution, created a roughly $28 million reparations fund in 2019.)

On campus and off, Hollander and Sandweiss reported, Princeton students encountered enslaved Black people who delivered wood to their rooms, tended nearby fields, or worked in town. John Witherspoon, the college’s sixth president and namesake of one of Princeton’s main streets downtown, was also a slave owner, despite espousing a philosophy that, according to Alabama historian Margaret Abruzzo, emphasized “human benevolence and sympathy as the foundations of all morality.” Still, Abruzzo wrote that Witherspoon’s teachings “gave a generation of students a language for challenging slavery.”

Princeton’s relationship with slavery was a complicated one. It considered itself, more than most schools at the time, a national university, where students from the North and South might exist in harmony. A substantial portion of the student body—almost two-thirds of the class of 1851, per Hollander and Sandweiss—hailed from slavery states. Princeton was relatively conservative, yet views on campus tended against slavery. Princeton was “ground zero” for the colonization movement, which advocated sending freed Black people to Africa or giving them segregated land.

There was some abolitionist sentiment on the fringe, but more notably, the college became “ground zero” for the colonization movement, which advocated sending freed Black people to Africa or providing them with land elsewhere so they might live apart from whites. (A group with ties to the college helped acquire the land that would become Liberia.)

Samuel Stanhope Smith, who succeeded Witherspoon as president of the college, had also kept enslaved people, yet “taught his students that slavery posed a particularly dire threat to the nation’s spiritual, moral, and political well-being,” Hollander and Sandweiss wrote. Yet Smith was no abolitionist. “No event,” he exclaimed, “can be more dangerous to a community than the sudden introduction into it of vast multitudes of persons, free in their condition, but without property, and possessing only habits and vices of slavery.”

Smith also wrote that “neither justice nor humanity requires that [a] master, who has become the innocent possessor of that property, should impoverish himself for the benefit of the slave.”

Upon moving to Princeton in 1813, according to Hollander and Sandweiss, the college’s eighth president, Ashbel Green, “purchased a 12-year-old named John and an 18-year-old named Phoebe to work as servants in the house. Green wrote in his diary that he would free them each at the age of 25, or 24 ‘if they served me to my entire satisfaction.’”

As a kid, I’d always imagined abolitionists as a righteous and heroic lot. Indeed, they faced fierce and sometimes violent backlash from pro-slavery forces. (Hollander and Sandweiss recall an incident in 1835 wherein a group of Princeton students set out to lynch a white abolitionist; they ended up running him out of town.)

Only later did I learn that very few abolitionists supported equal rights for Black people. There was widespread fear, as Smith expressed, that freeing the slaves and giving them rights posed a threat to the republic, one even greater than the national dispute over slavery. Slave owners, meanwhile, were terrified of retribution and fiercely protective of their “property.”

So while white abolitionists loathed the institution, as Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. points out in his book Stony the Road, most remained white supremacists. Even Abraham Lincoln, who sometimes used the n-word, proclaimed, during a Senate campaign debate with his incumbent rival, Sen. Stephen Douglas, “I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races.”

“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races,” Abraham Lincoln proclaimed during one debate.

“I agree with Judge Douglas that [the Black man] is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment,” Lincoln said. “But in the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is…the equal of every living man.”

Gates notes that when the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass attended northern anti-slavery rallies, he “suffered a considerable amount of jeering, harassment, and even physical abuse.” As Douglass wrote in his own newspaper, The North Star: “The feeling (or whatever it is) which we call prejudice, is no less than a murderous, hell-born hatred of every virtue which may ever adorn the character of a Black man.”

Getting back to higher education, which was (and remains) the most effective path to upward mobility, restitution seems in order from many an academic institution—Dartmouth is another example—not just for their direct role in slavery, but for how long it took them to start offering Black people an education.

Princeton’s first Black students weren’t admitted until 1945, part of a Navy-sponsored program, and women weren’t allowed in until 1969. (“If Princeton goes coeducational…PRINCETON IS DEAD,” protested one alum.) Harvard proved more progressive, graduating its first Black man in 1870 and opening its doors to women, via sister college Radcliffe, in 1920.

But even today most of these universities hang onto the nepotistic practice of legacy admissions, which runs counter to any notion of fairness and restitution. A 2018 survey of admissions directors by Inside Higher Ed found that 42 percent of private colleges and 6 percent of public ones gave an admissions boost to the children of alumni, and sometimes to the grandchildren and siblings of alumni.

In a survey by the school paper, 43 percent of Harvard’s legacy students said their parents made at least $500,000 a year.

Freshman classes at legacy schools are typically 10 percent to 20 percent descendants of alumni—which rivals and sometimes exceeds the enrollment of underrepresented racial groups. A survey of Harvard’s class of 2019 by the campus paper, the Crimson, found that 28 percent of incoming freshman had one or more alumni relatives, and nearly 17 percent had at least one alumni parent. Of the direct legacies in the survey, 43 percent said that their parents earned at least $500,000 a year.

For the classes of 2000 through 2019, Harvard’s average legacy acceptance rate was about 34 percent, compared with 6 percent for non-legacies, according to an analysis commissioned by an (ironically) anti-affirmative action group that is challenging Harvard’s admissions policies in court. At Stanford, the legacy admissions rate is about three times the non-legacy rate. At Dartmouth, which also has legacy admissions, 15 percent of the class of 2025 are children of alumni.

The Daily Princetonian, Princeton’s campus paper, reported that just 2 percent of the 35,370 students applying for the class of 2022 were legacies, but nearly one-third of them were accepted. That’s compared with an overall admissions rate of 5.5 percent, 6.2 percent for students of color. The resulting class was more than 14 percent legacy students. In his 2016 book The Price of Admission, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Daniel Golden wrote that elite private colleges, as a condition of their tax-exempt status, are prohibited from engaging in racial discrimination, yet the legacies who suck up slots at the expense of other qualified students are overwhelmingly wealthy and white.

Alumni will make up lots of rationales for the legacy system, but the reality is that it has nothing to do with merit and everything to do with the fact that legacies and their families are viewed by colleges as likely donors. So despite efforts by some to make amends for their actions in the past, most Ivy League schools, and others, continue to put financial self-interest above all that’s right and fair.

No comments:

Post a Comment