Supreme Court rules against Arizona inmates in right-to-counsel case

The ruling will make it harder for certain inmates who believe their lawyers failed to give them proper representation.

May 24, 2022

WASHINGTON (AP) — U.S. The Supreme Court ruled along ideological lines on Monday against two Arizona death row inmates who had argued that their lawyers did a poor job representing them in state court. The ruling will make it harder for certain inmates sentenced to death or long prison terms who believe their lawyers failed to bring challenges on those grounds.

The ruling involves cases brought to federal court after state court review. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the court’s six-justice conservative majority that the proper role for federal courts in these cases is a limited one and that federal courts are generally barred from taking in new evidence of ineffective assistance of counsel that could help prisoners. He wrote that “federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality” of state criminal trials.

In a dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor called her colleagues’ decision “perverse” and “illogical.” She said it “hamstrings the federal courts’ authority to safeguard” a defendant’s right to an effective lawyer, a right guaranteed by the Constitution’s Sixth Amendment. Sotomayor said the decision will “will leave many people who were convicted in violation of the Sixth Amendment to face incarceration or even execution without any meaningful chance to vindicate their right to counsel.”

The ruling will make it harder for certain inmates who believe their lawyers failed to give them proper representation.

May 24, 2022

WASHINGTON (AP) — U.S. The Supreme Court ruled along ideological lines on Monday against two Arizona death row inmates who had argued that their lawyers did a poor job representing them in state court. The ruling will make it harder for certain inmates sentenced to death or long prison terms who believe their lawyers failed to bring challenges on those grounds.

The ruling involves cases brought to federal court after state court review. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the court’s six-justice conservative majority that the proper role for federal courts in these cases is a limited one and that federal courts are generally barred from taking in new evidence of ineffective assistance of counsel that could help prisoners. He wrote that “federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality” of state criminal trials.

In a dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor called her colleagues’ decision “perverse” and “illogical.” She said it “hamstrings the federal courts’ authority to safeguard” a defendant’s right to an effective lawyer, a right guaranteed by the Constitution’s Sixth Amendment. Sotomayor said the decision will “will leave many people who were convicted in violation of the Sixth Amendment to face incarceration or even execution without any meaningful chance to vindicate their right to counsel.”

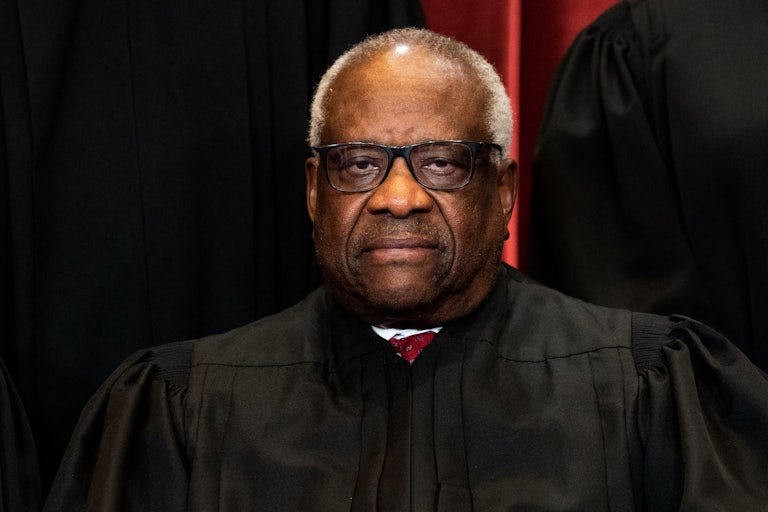

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the 6-3 majority opinion in the ruling against two Arizona death row inmates who claimed that they received inadequate counsel in their trials. (AP Photo/John Amis, File)

Sotomayor was joined by fellow liberals Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer, who is retiring this summer.

The case before the court involved Barry Lee Jones, who was convicted in the death of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, who died after a beating ruptured her small intestine. It also involved David Martinez Ramirez, who was convicted of using scissors to fatally stab his girlfriend in the neck and fatally stabbing her 15-year-old daughter with a box cutter.

In both cases the men argued they were failed by lawyers who handled their initial state court trials and then by lawyers, called post-conviction counsel, that handled a state review of their cases after appeals failed. The post-conviction lawyers allegedly erred by not arguing that the trial counsel was ineffective. The men then took their cases to federal court.

A Supreme Court ruling from 2012 opened an avenue for prisoners to make ineffective assistance of counsel claims in federal court. But on Monday the court said the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act bars federal courts from developing new evidence related to the ineffectiveness of the post-conviction lawyers. Sotomayor and an attorney for Jones and Lee said the decision takes out the “guts” of the earlier ruling.

In Jones’ case a federal court judge ordered him released or retried after finding lawyers failed first by not presenting evidence he was innocent and then, after his appeals failed, neglecting to argue his lawyer was ineffective. The Supreme Court’s decision reinstates his conviction, his lawyers said.

Ramirez, for his part, argued his trial lawyer failed to investigate or present evidence he has an intellectual disability and experienced severe physical abuse and neglect. A lawyer he was assigned after appeals failed didn’t raise an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. Ramirez argued presenting that evidence should have ruled out the death penalty. The high court’s decision means he won’t get that chance, his lawyers said.

In a statement, Arizona Attorney General Brnovich praised the ruling.

“I applaud the Supreme Court’s decision because it will help refocus society on achieving justice for victims, instead of on endless delays that allow convicted killers to dodge accountability for their heinous crimes,” he said.

Also Read:

EXPLAINER: How South Carolina execution firing squad works

But Robert Loeb, who argued Jones and Ramirez’ case at the high court, called it a “sad day.” The ruling “leaves the fundamental constitutional right to trial counsel with no effective mechanism for enforcement in these circumstances,” Loeb said in a statement.

Nearly 20 states, led by Texas, urged the justices to side with Arizona. The case is Shinn v. Ramirez, 20-1009.

Sotomayor was joined by fellow liberals Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer, who is retiring this summer.

The case before the court involved Barry Lee Jones, who was convicted in the death of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, who died after a beating ruptured her small intestine. It also involved David Martinez Ramirez, who was convicted of using scissors to fatally stab his girlfriend in the neck and fatally stabbing her 15-year-old daughter with a box cutter.

In both cases the men argued they were failed by lawyers who handled their initial state court trials and then by lawyers, called post-conviction counsel, that handled a state review of their cases after appeals failed. The post-conviction lawyers allegedly erred by not arguing that the trial counsel was ineffective. The men then took their cases to federal court.

A Supreme Court ruling from 2012 opened an avenue for prisoners to make ineffective assistance of counsel claims in federal court. But on Monday the court said the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act bars federal courts from developing new evidence related to the ineffectiveness of the post-conviction lawyers. Sotomayor and an attorney for Jones and Lee said the decision takes out the “guts” of the earlier ruling.

In Jones’ case a federal court judge ordered him released or retried after finding lawyers failed first by not presenting evidence he was innocent and then, after his appeals failed, neglecting to argue his lawyer was ineffective. The Supreme Court’s decision reinstates his conviction, his lawyers said.

Ramirez, for his part, argued his trial lawyer failed to investigate or present evidence he has an intellectual disability and experienced severe physical abuse and neglect. A lawyer he was assigned after appeals failed didn’t raise an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. Ramirez argued presenting that evidence should have ruled out the death penalty. The high court’s decision means he won’t get that chance, his lawyers said.

In a statement, Arizona Attorney General Brnovich praised the ruling.

“I applaud the Supreme Court’s decision because it will help refocus society on achieving justice for victims, instead of on endless delays that allow convicted killers to dodge accountability for their heinous crimes,” he said.

Also Read:

EXPLAINER: How South Carolina execution firing squad works

But Robert Loeb, who argued Jones and Ramirez’ case at the high court, called it a “sad day.” The ruling “leaves the fundamental constitutional right to trial counsel with no effective mechanism for enforcement in these circumstances,” Loeb said in a statement.

Nearly 20 states, led by Texas, urged the justices to side with Arizona. The case is Shinn v. Ramirez, 20-1009.

This SCOTUS Decision Makes Plain the Entire Sweep of the Conservative Majority

The court has a sweet tooth for vengeful law enforcement against certain groups of citizens.

Writing for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas—who has a lot on his mind these days—explained the Court’s decision thusly:

In our dual-sovereign system, federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality “of the trial of a criminal case in state court.” Wainwright, 433 U. S., at 90. That is the moment at which “[s]ociety’s resources havebeen concentrated . . . in order to decide, within the limits of human fallibility, the question of guilt or innocence of one of its citizens.” Ibid.; see also Herrera v. Collins, 506 U. S. 390, 416 (1993); Davila, 582 U. S., at (slip op., at 8). Such intervention is also an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them. Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case.

Man, this is some bloodless shit right here. We must maintain what appears to be an unjust death sentence lest people begin to question how our state courts parcel out unjust death sentences. You don’t have to be completely familiar with all aspects of our two-tiered justice system to realize that Thomas’ opinion is another demonstration that the carefully engineered conservative majority on the Supreme Court is deliberately obtuse about the world in which the rest of us live. Justice Sonia Sotomayor certainly can see a church by daylight in this regard, as she demonstrates in her flamethrower of a dissent.

This decision is perverse. It is illogical: It makes no sense to excuse a habeas petitioner’s counsel’s failure to raise a claim altogether because of ineffective assistance in post- conviction proceedings, as Martinez and Trevino did, but to fault the same petitioner for that postconviction counsel’s failure to develop in support of the trial-ineffectiveness claim. In so doing, the Court guts Martinez’s and Trevino’s core reasoning. The Court also arrogates power from Congress: The Court’s analysis improperly reconfigures the balance Congress struck in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) between state interests and individual constitutional rights.

Ah, the old AEDPA, a gift to the American judiciary from the triangulations of the Clinton White House. Passed in April of 1996, the law was a key piece of President Clinton’s re-election pitch, and it was one of the biggest whacks taken out of habeas corpus since the Founders wrote the Great Writ into the Constitution. Sotomayor points out that, on Monday, the Court diluted even the habeas guarantees that the AEDPA left in place, as well as de facto reversing a precedent that would have allowed the two prisoners to press their claims.

In this godawful decision, the entire sweep of the carefully engineered conservative majority is made plain — disrespect for precedent, disrespect for the plain language of inconvenient parts of the law, untoward respect for what this Court believes to be the prerogatives of state governments, and a sweet tooth for vengeful law enforcement against certain specific groups of citizens. These two men are not the only things under sentence of death these days.

The court has a sweet tooth for vengeful law enforcement against certain groups of citizens.

ESQUIRE

May 24, 2022

THE WASHINGTON POSTGETTY IMAGES

It was a Monday in spring and so it was time once again for the Supreme Court to explain why some poor sods of whom you’ve never heard are screwed eight ways from Sunday. Monday’s lucky winners were David Ramirez and Barry Lee Jones, temporarily housed on Death Row in Arizona. These two argued that their lawyers in their state trials were sufficiently incompetent as to violate their Sixth Amendment guarantees. Ramirez said his trial counsel failed to investigate his intellectual disability and Jones said his lawyer blew off evidence that Jones may not have committed his crime at all.

In 2017, a federal judge overturned Jones’ conviction and offered he prosecution the choice of retrying Jones or releasing him. The state of Arizona found a third option. It appealed that judge’s ruling and, on Monday, through its carefully engineered 6-3 conservative majority, agreed with the state. Barry Lee Jones will stay on Death Row.

THE WASHINGTON POSTGETTY IMAGES

It was a Monday in spring and so it was time once again for the Supreme Court to explain why some poor sods of whom you’ve never heard are screwed eight ways from Sunday. Monday’s lucky winners were David Ramirez and Barry Lee Jones, temporarily housed on Death Row in Arizona. These two argued that their lawyers in their state trials were sufficiently incompetent as to violate their Sixth Amendment guarantees. Ramirez said his trial counsel failed to investigate his intellectual disability and Jones said his lawyer blew off evidence that Jones may not have committed his crime at all.

In 2017, a federal judge overturned Jones’ conviction and offered he prosecution the choice of retrying Jones or releasing him. The state of Arizona found a third option. It appealed that judge’s ruling and, on Monday, through its carefully engineered 6-3 conservative majority, agreed with the state. Barry Lee Jones will stay on Death Row.

Writing for the majority, Justice Clarence Thomas—who has a lot on his mind these days—explained the Court’s decision thusly:

In our dual-sovereign system, federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality “of the trial of a criminal case in state court.” Wainwright, 433 U. S., at 90. That is the moment at which “[s]ociety’s resources havebeen concentrated . . . in order to decide, within the limits of human fallibility, the question of guilt or innocence of one of its citizens.” Ibid.; see also Herrera v. Collins, 506 U. S. 390, 416 (1993); Davila, 582 U. S., at (slip op., at 8). Such intervention is also an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them. Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case.

Man, this is some bloodless shit right here. We must maintain what appears to be an unjust death sentence lest people begin to question how our state courts parcel out unjust death sentences. You don’t have to be completely familiar with all aspects of our two-tiered justice system to realize that Thomas’ opinion is another demonstration that the carefully engineered conservative majority on the Supreme Court is deliberately obtuse about the world in which the rest of us live. Justice Sonia Sotomayor certainly can see a church by daylight in this regard, as she demonstrates in her flamethrower of a dissent.

This decision is perverse. It is illogical: It makes no sense to excuse a habeas petitioner’s counsel’s failure to raise a claim altogether because of ineffective assistance in post- conviction proceedings, as Martinez and Trevino did, but to fault the same petitioner for that postconviction counsel’s failure to develop in support of the trial-ineffectiveness claim. In so doing, the Court guts Martinez’s and Trevino’s core reasoning. The Court also arrogates power from Congress: The Court’s analysis improperly reconfigures the balance Congress struck in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) between state interests and individual constitutional rights.

Ah, the old AEDPA, a gift to the American judiciary from the triangulations of the Clinton White House. Passed in April of 1996, the law was a key piece of President Clinton’s re-election pitch, and it was one of the biggest whacks taken out of habeas corpus since the Founders wrote the Great Writ into the Constitution. Sotomayor points out that, on Monday, the Court diluted even the habeas guarantees that the AEDPA left in place, as well as de facto reversing a precedent that would have allowed the two prisoners to press their claims.

In this godawful decision, the entire sweep of the carefully engineered conservative majority is made plain — disrespect for precedent, disrespect for the plain language of inconvenient parts of the law, untoward respect for what this Court believes to be the prerogatives of state governments, and a sweet tooth for vengeful law enforcement against certain specific groups of citizens. These two men are not the only things under sentence of death these days.

The Supreme Court Decides Death Row Prisoners Don’t Deserve Competent Lawyers

The court’s conservatives have pared back the Sixth Amendment’s protections so that it won’t impede the state’s ability to erroneously execute the innocent.

ERIN SCHAFF/GETTY IMAGES

The majority opinion authored by Justice Clarence Thomas in Shinn v. Ramirez will severely restrict many Americans from using their Sixth Amendment protections.

If you’re charged with a serious crime and you can’t afford a lawyer, the government has to provide you with one. (That is, for now.) There are about 1.5 million lawyers in the United States. Many of them are good at their jobs. But some of them aren’t, for various reasons. Maybe they’re overworked and juggling too many cases. Maybe they don’t have the resources they need to vigorously advocate for their clients. Maybe they’re out of their depth on a particular case. Maybe they just aren’t cut out for their current line of work.

David Martinez Ramirez and Barry Lee Jones, two Arizona death-row prisoners, think that their respective lawyers did a bad job of defending them. (Their cases are unrelated, except for this particular legal issue.) The two men told the Supreme Court last year that they were harmed by “ineffective assistance of counsel,” as the courts call it, at two separate stages: first, by their trial lawyers not representing them well in front of a jury and then, again, by their state appellate lawyers not properly challenging their convictions because of their trial lawyers’ allegedly shoddy work. They wanted a new trial to fix the problem.

When you think your constitutional rights were violated by a state court, you can theoretically challenge your conviction in the federal courts. The Sixth Amendment protects the right to legal counsel, and the courts have logically interpreted this as the right to effective legal counsel because otherwise, the right to an attorney wouldn’t be worth the parchment on which it was printed. Ramirez and Jones now have federal appellate lawyers—and effective ones, to boot—who asked a federal district court to overturn their clients’ respective convictions because their previous lawyers weren’t good enough at their jobs. Since the two men are on death row, the stakes are as high as they get.

Introductory offer: 50% off fearless reporting.1 year for $10.Subscribe

On Monday, the Supreme Court said no. The court, in a 6–3 decision that fell along the usual ideological lines, ruled that the two men couldn’t introduce new evidence that their previous lawyers were ineffective when asking the federal courts to intervene. The decision is a chilling reminder that the court’s conservative majority need not overturn a constitutional right, as it will in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, to destroy it—the justices can simply pare it back into oblivion.

“This decision is perverse,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. “It is illogical: It makes no sense to excuse a habeas petitioner’s counsel’s failure to raise a claim altogether because of ineffective assistance in post-conviction proceedings … but to fault the same petitioner for that post-conviction counsel’s failure to develop evidence in support of the trial-ineffectiveness claim.”

An Arizona jury convicted Jones of the murder of his girlfriend’s four-year-old daughter. Prosecutors argued that her fatal injuries occurred while she was in Jones’s custody; Jones’s lawyer failed to introduce “readily available medical evidence that could have shown that Rachel sustained her injuries when she was not in Jones’ care,” Sotomayor noted in her dissent. The Intercept’s Liliana Segura has also reported on serious flaws in the prosecution’s case—and, just as troublingly, glaring oversights by Jones’s defense during his trial that could have affected his conviction.

Ramirez was convicted of murdering his girlfriend and daughter and received a death sentence. During the sentencing phase in capital trials, lawyers from both sides present mitigating and aggravating evidence for the jury to consider when passing its sentence. Ramirez said that his trial lawyers failed to build evidence about his intellectual disabilities, including his mother’s history of drinking when pregnant with him, evidence of her abuse toward him as a young child, and his signs of developmental delays. On appeal, Ramirez’s lawyer admitted in an affidavit that she was not prepared enough to handle “the representation of someone as mentally disturbed” as him.

In theory, these ineffective-assistance claims could be resolved on appeal by better lawyers. But indigent defendants are all too often represented by ineffective lawyers during their state appeals, as well, compounding the constitutional problems. These shortcomings are clear enough that the Supreme Court sided with defendants on the issue in the 2012 decision Martinez v. Ryan and then in the 2013 decision Trevino v. Thaler. In those decisions, the justices allowed federal courts to hear ineffective-counsel claims from the trial phase even if the defendant’s state appeals lawyer (also ineffectively) failed to preserve that claim on appeal. One bad turn, in other words, did not deserve another.

Monday’s ruling clawed back those protections without overturning them. One problem with having an ineffective lawyer during state appeals is that they might not develop evidence of ineffective assistance by their trial court predecessor. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, ruling in both Jones’s case and Ramirez’s case, held that federal courts could hold evidentiary hearings so that the two men could prove their cases. In his majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas said that these hearings weren’t allowed.

“In our dual-sovereign system, federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality of the trial of a criminal case in state court,” he claimed, paraphrasing from past Supreme Court decisions. It is there, Thomas argued, that evidence should be presented, even if the defendant is assigned an incompetent lawyer. “Such intervention is also an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them,” he went on to add. “Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case.”

Thomas even complained that the federal court had held a seven-day hearing in Jones’s case where it heard from 10 witnesses, all of whom cast serious doubt on the validity of Jones’s conviction. “Of these witnesses, only one of the forensic pathologists and the lead detective testified at the original trial,” Thomas noted. “The remainder testified on virtually every disputed issue in the case, including the timing of Rachel Gray’s injuries and her cause of death. This wholesale relitigation of Jones’ guilt is plainly not what Martinez envisioned.” A layperson who hears of this might reasonably think that the problem here isn’t really with the evidentiary hearing itself.

This is a perennial theme in death-row cases before these justices, where abstract interests like the finality of state convictions, the economy of judicial resources, and respect for state-federal relations are prioritized over the real substance of a defendant’s constitutional rights. Typically, in our system it is the people who have rights, while the government has only powers that are bound by them. But in the Roberts court’s imagination, the states have the right to execute death-row prisoners, and all these pesky attempts by death-penalty abolitionists and capital defense lawyers to stop them from carrying out executions are just an infringement of that right.

Sotomayor argued that, as a consequence of Monday’s ruling, indigent defendants in these circumstances in states like Arizona won’t be able to develop the factual record necessary to seek Sixth Amendment relief. “For the subset of these petitioners who receive ineffective assistance both at trial and in state post-conviction proceedings, the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee is now an empty one,” she wrote. “Many, if not most, individuals in this position will have no recourse and no opportunity for relief. The responsibility for this devastating outcome lies not with Congress, but with this Court.”

As I’ve noted before, this roster of Supreme Court justices appears committed to letting executions go forward in almost every circumstance imaginable. Principles that are cherished in other contexts, most notably religious freedom, are set aside so that states can administer lethal injections to their citizens. The justices’ enmity toward death-row prisoners and their lawyers is a breeding ground for constitutional violations—and if Monday’s ruling for Jones in particular is any indication, the possibility that they will sanction the execution of someone who might be actually innocent of their crimes.

No comments:

Post a Comment