IT'S PLANTING TIME

Grow tomatoes, not carrots and other tips for keeping lead out of your garden produce

Chicago soil can contain high levels of lead and other heavy metals.

Check out this guide to making gardening safer.

Kat Powers has grown herbs, tomatoes and native plants in her garden in Andersonville.

“I’ve been lucky enough to have dug up two backyards,” she said. She’s about to start planting a

new summer garden in Lincoln Square. This time the project is more “ambitious,” as she plans to grow tomatoes, eggplant, squash, peppers and maybe even some peas.

While Kat enjoys gardening and considers it a healing practice, she’s always wondered whether any of the pollutants in the soil, things like lead and other heavy metals, actually seep into the stuff she’s growing. And if they do, she wonders whether there are things she can do to try to minimize any health risks. So she wrote into Curious City to find out.

These are good questions because decades of industrial pollution from heavy industry, the use of lead paint on older homes (federal restrictions were not imposed until the late 1970s), gasoline exhaust and old plumbing infrastructure made with lead can all contaminate the soil. Once accumulated in the soil, heavy metals like lead lurk indefinitely and if ingested, can pose health risks including developmental issues in children and heart problems in adults.

Since lead occurs naturally in soil, we’ve all been exposed to a little lead. But “the dose matters,” said Gabriel Filippelli, a professor of earth sciences and director of the Center for Urban Health at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis. In urban settings Filippelli says it’s possible to find as much as 100 times the natural levels of lead due to contamination. Plus, where there is lead, you usually find other heavy metal contaminants like mercury and arsenic.

In a recent study, Andrew Margenot, a University of Illinois crop sciences researcher took 2,000 soil samples from across Chicago backyards and parkways and found the city’s median soil lead level is 220 parts per million (ppm) — that’s ten times higher than the 20 ppm natural level. Margenot also found that 20 percent of the city exceeds the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency’s safe limit of 400 ppm for growing crops, and all of the city is well above the California EPA state limit of 80 ppm. Some areas on the South and West Sides exceed 1,000 ppm.

So what does that mean for gardeners like Kat and the city’s nearly 900 community gardens growing produce in that soil? Here’s what you need to know about how likely it is your produce might be contaminated with lead, how to get your soil tested and what you can do to minimize the risks of growing contaminated produce.

How does lead get into your produce in the first place?

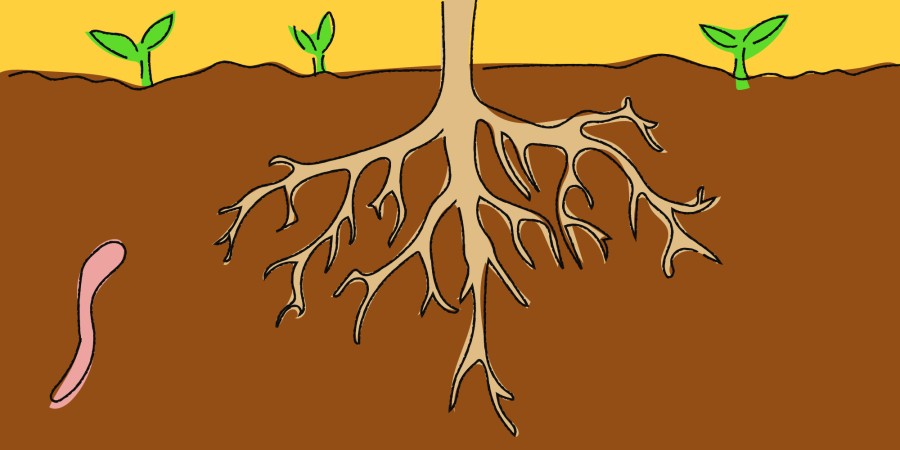

Lead finds its way into plants in two main ways. The first is through adhesion — that’s when dust from the soil containing lead sticks to the surface of plants like tomatoes or kale and can get into your body if you don’t thoroughly wash it. That’s a problem for some leaf and root vegetables that are difficult to wash thoroughly.

The second way lead can enter produce is by uptake. That’s when lead in the soil gets sucked up into a plant’s vascular system through its roots. That can happen in two ways, U of I’s Margenot said. First, harmful heavy metals closely mimic the shape and size of nutrients the plant wants — for example, to a plant, lead looks a lot like calcium and arsenic looks a lot like phosphorus. That allows them to enter roots undetected through ion transport channels designed to let in nutrients.

“These ion transport channels in the roots, they’re like tiny doors … like a puzzle piece, if the metal is the right size and fit, it’ll sneak in,” Margenot said.

Heavy metals can also bypass those ion transport channels completely and break in by building up on top of a root’s protective film barrier layer, which then breaks like a dam under the pressure.

Once inside the plant’s vascular system, heavy metals move around and accumulate in edible tissue, like leaves and fruit.

Avoid the roots and shoots, go for the fruits

That old gardener’s adage turns out to be pretty good advice, Margenot said. The idea is that the most lead accumulates in a plant’s roots, with less in the leaves and even less in the fruits.

Tomatoes are a good example. In the first study of lead uptake in Chicago garden plants, Margenot found that even when the soil they were grown in had 1200 ppm of lead (the EPA says not to grow produce in soil with more than 400 ppm), lead levels were high in the plants leaves but low in the tomatoes.

Besides tomatoes, Margenot recommends growing fruiting vegetables, things like zucchini and cucumbers.

Peppers, melons and strawberries are also good options, Filipelli added.

Though his study didn’t address root vegetables, Margenot said he would avoid growing them altogether in Chicago soil.

“For root crops like carrots, or onions, or potatoes, even if you peel them, you still may have this higher lead in the tissue,” Margenot said. “So I think it’s fair to say that if you’ve got a high amount of lead in your soil, you just don’t want to put in root vegetables.”

How do you know if you should be concerned about the level of lead in your soil?

You can find your neighborhood on the soil lead level map Margenot created. If you’re in a hotspot, above about 200 ppm, you should definitely get your soil tested before planting crops, he said.

Gardener Amy Olson, who runs communications for the 1,800-member Chicago Community Gardeners Association, tests the soil in her Humboldt Park community garden every few years. She says their lead levels have remained below 100 ppm but it’s important to continue testing, especially when construction happens nearby.

“Lead contamination is kind of a given in Chicago,” she said. “Anytime someone starts a new community garden, getting a soil test with a heavy metal screen is an absolute necessity.”

If you’re gardening near an old home, a street or an old industrial site, it’s fairly likely your soil is contaminated, Margenot said. So it’s helpful to know the history of your yard — were there sheds or other structures in the past that have since been removed? When in doubt, Margenot said, avoid growing crops within 10 feet of streets and structures.

“Typically, most people’s backyards in Chicago have issues from paint chips that are falling off from old houses. So putting a garden bed right next to your house, if that house has paint from before 1980, that’s not a good idea,” he added.

How can you test your soil?

The University of Illinois Extension maintains a list of commercial labs that test soil samples using a heavy metals panel that looks for lead, cadmium, arsenic, mercury, zinc and cobalt. Depending on the lab, tests can cost between $30-100 per sample.

Indiana University also offers free soil test kits and free soil testing.

If you want to test your soil, there are a few important things to keep in mind. First, you should take your sample from the first couple of inches of soil, where lead concentrations tend to be highest. Make sure your sample is dry when you send it in. And don’t mix samples from different locations together. It’s a good idea to take distinct samples from areas of your yard you manage differently and to keep them separate when you send them to the lab. You can also send in samples from certain distances away from structures to see where the contamination drops off.

Soil tests can also tell you about your garden’s fertility — the essential nutrients that are present and your soil’s pH.

There are some ways to reduce contamination and exposure

If you choose to plant directly in contaminated soil, you can minimize adhesion (that’s contaminated soil dust that sticks to the edible parts of plants) by “mulching the heck out of it” with straw or woodchips to prevent soil from being kicked up onto fruits or leaves when it rains, Margenot said.

But it’s much safer to avoid planting directly in heavily contaminated soil by building raised beds, filling them with fresh soil or compost, and using landscaping fabric to separate the bed from the ground.

It’s not a given that the soil you buy is safe to use either. You should test the soil you use to fill your raised beds yourself, or insist the company you’re buying from does a test, Margenot said. If you’re buying yard waste-based compost, it could contain high lead levels from the leaf tissue of decomposed grass clippings. A safer bet for clean soil is the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, Margenot said.

“MWRD will give you biosolids, or composted human feces, which I know sounds wicked gross, but they’re always tested for lead and they’re actually very, very safe to use,” Margenot said. “I use them in my own garden and they’re a great compost.”

And it’s not just fruits and vegetables you have to worry about. Dust from lead-contaminated gardens can also be directly harmful to your health.

“You inhale that dust when you’re working the soil, and that goes right into your body,” Margenot said. “The fruit might be lead free, but the soil still presents a risk. I wouldn’t be comfortable working soil with a hoe above 400 ppm because of that dust.”

To stay safe, the University of Illinois Extension recommends always wearing gloves when gardening, wearing a mask to avoid soil inhalation, leaving shoes outdoors and carefully washing hands after gardening. Children should not be allowed to play in contaminated soil, as they are at higher risk of lead poisoning.

More about our question-asker

Chicago native Kat Powers has always been an avid gardener. She attributes her love of gardening to her mother, who grew drought-resistant plants in California in the mid-1980s and ’90s.

Kat said she’s often wondered about the ability of toxins to get into fruit and plant leaves since she started growing produce a decade ago at her previous home in Andersonville.

This summer, she’ll be planting an extensive garden with tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, squash, onions, lettuce and even a pergola of native grapes as part of a work exchange for a woman in Lincoln Square.

Regarding her question, Kat said, “I’m delighted to have it addressed because I’ve talked to a lot of people about it and everyone was like, ‘I had no idea that this was an issue.’ I’m definitely going to have to start testing the soil.”

When she’s not gardening, Kat works as a potter at Lillstreet Art Center and at Bistro Campagne in Lincoln Square.

No comments:

Post a Comment