Delving into the archives of British archaeologist Howard Carter, who led the mission down to the pharaoh’s burial chamber, the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries shines a spotlight on the immense contribution of the locals — a role largely overlooked by history.

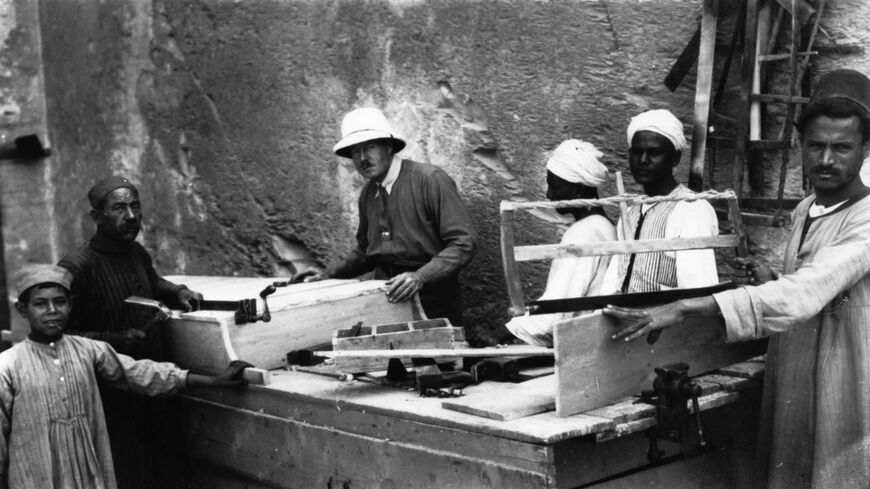

English Egyptologist Howard Carter (1874-1939) supervises carpenters preparing to reseal Tutankhamen's tomb, circa 1923. - Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Marc Espanol

AL-MONITOR

May 23, 2022

At the end of 1922, a few months after Egypt formally declared its independence, the field of archaeology reached a historic milestone with the discovery of the largely intact tomb of Tutankhamun. The discovery of the royal burial chamber, still considered one of the most culturally significant in history, gave way to eight years of excavation, clearance and documentation down to the last object in the tomb. A process that propelled the leader of the mission, the famous British archaeologist Howard Carter, to international fame.

Yet a century after the discovery, Egypt’s contribution to Carter’s archaeological mission and the process of unearthing, cleaning and preserving the collection that lay in the tomb of Ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaoh remains a largely neglected chapter of the feat. In the collective imagination, fame and recognition went almost exclusively to Carter.

This narrative, however, could not be further from the truth, and the discovery was never the work of a solitary British archaeologist. In an effort to see beyond this popular colonialist stereotype that still surrounds the discovery of the tomb, and to mark the centenary of the momentous event, the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries launched an exhibition April 13 that puts the spotlight on the often-overlooked Egyptians who were also involved in the mission and the crucial role they played. The project includes photographs, letters, plans, drawings and diaries from Carter’s archive.

“Archaeology is not Indiana Jones [but] a very meticulous process that takes a lot of time, and you need a lot of expertise and knowledge,” said Daniela Rosenow, Egyptologist at the University of Oxford and co-curator of the exhibition "Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive." She told Al-Monitor. “[We hope] that people understand that this was a 10-year process, and that that involved a team. It was not the story of one heroic man.”

Among the Egyptians who contributed to the mission in the tomb of Tutankhamun, the ones we have the least information about are the laborers who worked at the site. Most of these foremen and laborers came from villages around al-Qurna, a group of small villages near where the pharaoh’s tomb was discovered, according to a recent study by Hend Mohamed AbdelRahman, professor of Egypt’s Modern and Contemporary History at Minia University. In total, she estimates that between 75 and 175 laborers from this area participated in the excavation and clearance of the tomb.

But since Carter, unlike other archaeologists of the time, barely acknowledged these laborers in writing, very little is known about their histories. In fact, only four Egyptian foremen were repeatedly named, and thanked, by the British archaeologist. “Last of all come my Egyptian staff and the Reises who have served me throughout the heat and burden of many long days, whose loyal services will always be remembered by me with respect and gratitude and whose names are herewith recorded: Ahmed Gerigar, Hussein Ahmed Saide, Gad Hassan and Hussein Abou Owad,” wrote Carter in his second volume, in which he recounts the discovery of the pharaoh’s burial chamber.

AbdelRahman has been able to track down Hussein Ahmed Saide, about whom the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram came to write, as well as Gad Hassan, an antiquity’s trader from the village of al-Tarif employed by Carter. Yet the researcher notes that the most famous of the four was probably Ahmed Gerigar, a skilled foreman very close to Carter. It is believed that Gerigar, driven by his good knowledge of the site and refined intuition, encouraged and convinced Carter to keep excavating at the point where they later found the tomb of Tutankhamun when the British archaeologist had already begun to lose hope.

“These four are very famous because every month [Carter] is talking about whether they got their salaries or not,” AbdelRahman told Al-Monitor. “In my opinion, he didn’t want to lose them, or to give them a chance to work with others. He wanted them to continue because he believed in them,” she added.

Other names who participated in the mission that have been recorded include Boutros Tadros, who began working for Carter when he was just a boy and was later promoted to be in charge of scheduling the workforce’s shifts. Also, Abdel Maaboud Abdalla, the ex-chief guardian of the Theban Necropolis and a sub-photographer for Carter, and Tewfik Boulos, who worked as Carter’s secretary from 1902 to 1905 according to AbdelRahman.

The importance of the Egyptian workers in the mission was such that many of them even claimed that, in fact, Carter was not even present the day Tutankhamun’s tomb was found, something that the British archaeologist always denied. “Carter filed a case in court against someone who [mentioned] that he wasn’t present in the moment the tomb was excavated. This point will remain forever as a point of dispute,” AbdelRahman explained.

In addition to the workers at the site, Egyptian inspectors from the Antiquities Service also became very involved during the work of clearing the burial chamber, serving as a liaison between Carter’s team and the Egyptian authorities, AbdelRahman recounts. Among these were Abadir Effendi Michrqui Abadir, who supervised the excavation of the tomb; Ibrahim Mohamed Habib, a highly qualified inspector of the Antiquities Service in Luxor; and Saleh Hamdi, present during the process of examining the king’s mummy.

Another way in which the Egyptians contributed to the mission, AbdelRahman notes, is by assuming part of the financing of the project, which was key to ensuring the completion of the whole process and appears in the annual expenditure of the state budget.

Beyond their overall contribution to the discovery of the iconic tomb, AbdelRahman said that the feat was also key in spurring Cairo’s interest in investing in archaeology and taking a greater role in the preservation of its own archaeological treasures. Rosenow noted that the discovery was followed with great interest in Egypt as well, and that the figure of the pharaoh became a symbol of its recently declared independence.

“It helped to develop Egyptology and education as soon as possible, to allow Egyptians to take the place from foreigners and be responsible for the administration of antiquities,” AbdelRahman concluded.

“The Egyptian reaction to the discovery is an important aspect to touch upon. Because Egypt had become independent a few months earlier, and the discovery was an amazing thing. He became kind of the icon of the new independence and pride,” Rosenow noted.

May 23, 2022

At the end of 1922, a few months after Egypt formally declared its independence, the field of archaeology reached a historic milestone with the discovery of the largely intact tomb of Tutankhamun. The discovery of the royal burial chamber, still considered one of the most culturally significant in history, gave way to eight years of excavation, clearance and documentation down to the last object in the tomb. A process that propelled the leader of the mission, the famous British archaeologist Howard Carter, to international fame.

Yet a century after the discovery, Egypt’s contribution to Carter’s archaeological mission and the process of unearthing, cleaning and preserving the collection that lay in the tomb of Ancient Egypt’s most famous pharaoh remains a largely neglected chapter of the feat. In the collective imagination, fame and recognition went almost exclusively to Carter.

This narrative, however, could not be further from the truth, and the discovery was never the work of a solitary British archaeologist. In an effort to see beyond this popular colonialist stereotype that still surrounds the discovery of the tomb, and to mark the centenary of the momentous event, the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries launched an exhibition April 13 that puts the spotlight on the often-overlooked Egyptians who were also involved in the mission and the crucial role they played. The project includes photographs, letters, plans, drawings and diaries from Carter’s archive.

“Archaeology is not Indiana Jones [but] a very meticulous process that takes a lot of time, and you need a lot of expertise and knowledge,” said Daniela Rosenow, Egyptologist at the University of Oxford and co-curator of the exhibition "Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive." She told Al-Monitor. “[We hope] that people understand that this was a 10-year process, and that that involved a team. It was not the story of one heroic man.”

Among the Egyptians who contributed to the mission in the tomb of Tutankhamun, the ones we have the least information about are the laborers who worked at the site. Most of these foremen and laborers came from villages around al-Qurna, a group of small villages near where the pharaoh’s tomb was discovered, according to a recent study by Hend Mohamed AbdelRahman, professor of Egypt’s Modern and Contemporary History at Minia University. In total, she estimates that between 75 and 175 laborers from this area participated in the excavation and clearance of the tomb.

But since Carter, unlike other archaeologists of the time, barely acknowledged these laborers in writing, very little is known about their histories. In fact, only four Egyptian foremen were repeatedly named, and thanked, by the British archaeologist. “Last of all come my Egyptian staff and the Reises who have served me throughout the heat and burden of many long days, whose loyal services will always be remembered by me with respect and gratitude and whose names are herewith recorded: Ahmed Gerigar, Hussein Ahmed Saide, Gad Hassan and Hussein Abou Owad,” wrote Carter in his second volume, in which he recounts the discovery of the pharaoh’s burial chamber.

AbdelRahman has been able to track down Hussein Ahmed Saide, about whom the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram came to write, as well as Gad Hassan, an antiquity’s trader from the village of al-Tarif employed by Carter. Yet the researcher notes that the most famous of the four was probably Ahmed Gerigar, a skilled foreman very close to Carter. It is believed that Gerigar, driven by his good knowledge of the site and refined intuition, encouraged and convinced Carter to keep excavating at the point where they later found the tomb of Tutankhamun when the British archaeologist had already begun to lose hope.

“These four are very famous because every month [Carter] is talking about whether they got their salaries or not,” AbdelRahman told Al-Monitor. “In my opinion, he didn’t want to lose them, or to give them a chance to work with others. He wanted them to continue because he believed in them,” she added.

Other names who participated in the mission that have been recorded include Boutros Tadros, who began working for Carter when he was just a boy and was later promoted to be in charge of scheduling the workforce’s shifts. Also, Abdel Maaboud Abdalla, the ex-chief guardian of the Theban Necropolis and a sub-photographer for Carter, and Tewfik Boulos, who worked as Carter’s secretary from 1902 to 1905 according to AbdelRahman.

The importance of the Egyptian workers in the mission was such that many of them even claimed that, in fact, Carter was not even present the day Tutankhamun’s tomb was found, something that the British archaeologist always denied. “Carter filed a case in court against someone who [mentioned] that he wasn’t present in the moment the tomb was excavated. This point will remain forever as a point of dispute,” AbdelRahman explained.

In addition to the workers at the site, Egyptian inspectors from the Antiquities Service also became very involved during the work of clearing the burial chamber, serving as a liaison between Carter’s team and the Egyptian authorities, AbdelRahman recounts. Among these were Abadir Effendi Michrqui Abadir, who supervised the excavation of the tomb; Ibrahim Mohamed Habib, a highly qualified inspector of the Antiquities Service in Luxor; and Saleh Hamdi, present during the process of examining the king’s mummy.

Another way in which the Egyptians contributed to the mission, AbdelRahman notes, is by assuming part of the financing of the project, which was key to ensuring the completion of the whole process and appears in the annual expenditure of the state budget.

Beyond their overall contribution to the discovery of the iconic tomb, AbdelRahman said that the feat was also key in spurring Cairo’s interest in investing in archaeology and taking a greater role in the preservation of its own archaeological treasures. Rosenow noted that the discovery was followed with great interest in Egypt as well, and that the figure of the pharaoh became a symbol of its recently declared independence.

“It helped to develop Egyptology and education as soon as possible, to allow Egyptians to take the place from foreigners and be responsible for the administration of antiquities,” AbdelRahman concluded.

“The Egyptian reaction to the discovery is an important aspect to touch upon. Because Egypt had become independent a few months earlier, and the discovery was an amazing thing. He became kind of the icon of the new independence and pride,” Rosenow noted.

No comments:

Post a Comment