The Brief Life and Watery Death of a ’70s Libertarian Micronation

A wealthy American wanted to build an island republic. The king of Tonga had other ideas.

BY RAYMOND CRAIB

A wealthy American wanted to build an island republic. The king of Tonga had other ideas.

BY RAYMOND CRAIB

MAY 21, 2022

SLATE

SLATE

LONG READ

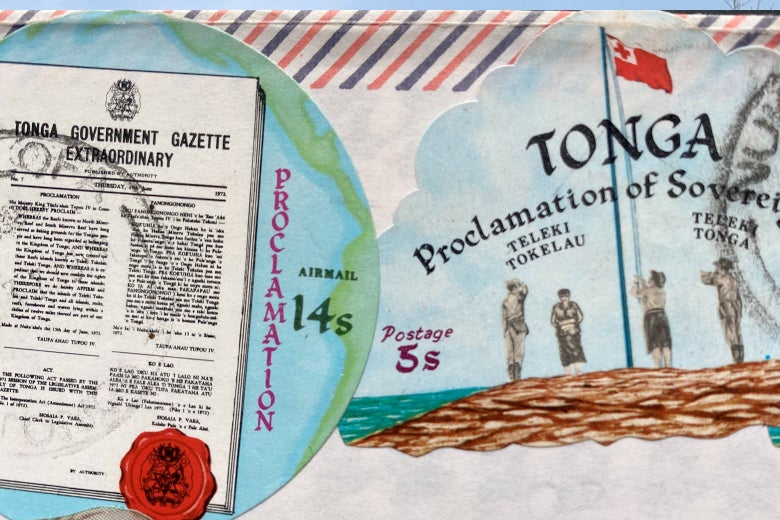

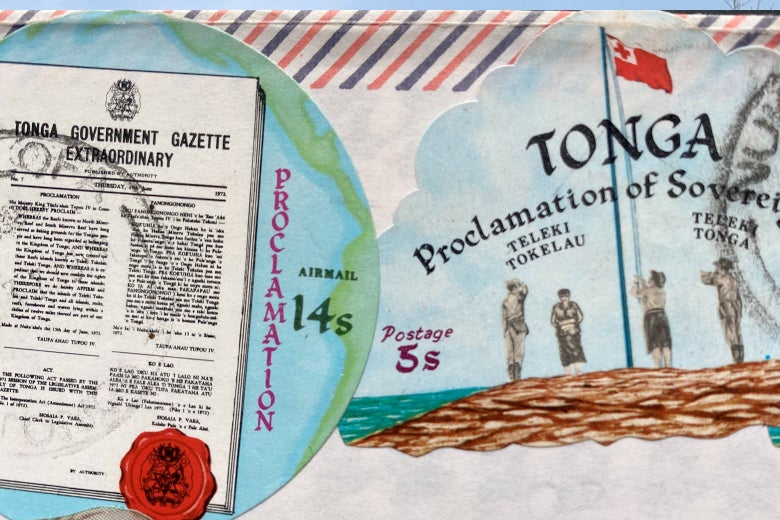

Stamps issued by the kingdom of Tonga commemorating taking possession of the Minerva Reefs. Photo illustration courtesy PM Press. Stamps from the collection of Raymond Craib.

Once upon a time, a wealthy man set out to establish his own country. He found a shallow reef over which the waters of a vast ocean had lapped since time immemorial. He hired a company to dredge the ocean floor and deposit the sand on the reef. An island would be born, upon which the man had a concrete platform built, a flag planted, and the birth of the Republic of Minerva declared. The monarch of a nearby island kingdom was not impressed. He opened the doors of his kingdom’s one jail and assembled a small army of prisoners. The monarch, his convicts, and a four-piece brass band boarded the royal yacht and descended upon the reef, where they promptly removed the flag, destroyed the platform, and deposed, in absentia, the man who would be king. And Minerva returned to the ocean

The story of Michael Oliver, his short-lived 1972 Republic of Minerva, and the response of the king of Tonga is not the stuff of fairy tales. Nor is it an uncommon story, an isolated event ripe for consumption as a chronicle of crazy rich Caucasians. In the U.S. after World War II, with the dramatic geopolitical changes wrought by decolonization and the Cold War, battles were waged over the meaning of ideals such as democracy and freedom, often pitting those who believed individual liberty to be more important than social equality against those who prioritized the latter over the former. In the midst of such struggles, individuals concerned with protecting their wealth, their safety, and their freedom from what they perceived to be an overbearing government and a threatening rabble sought to exit the U.S. and to establish their own independent, sovereign, and private countries on the ocean and in island spaces. It usually did not end well.

Once upon a time, a wealthy man set out to establish his own country. He found a shallow reef over which the waters of a vast ocean had lapped since time immemorial. He hired a company to dredge the ocean floor and deposit the sand on the reef. An island would be born, upon which the man had a concrete platform built, a flag planted, and the birth of the Republic of Minerva declared. The monarch of a nearby island kingdom was not impressed. He opened the doors of his kingdom’s one jail and assembled a small army of prisoners. The monarch, his convicts, and a four-piece brass band boarded the royal yacht and descended upon the reef, where they promptly removed the flag, destroyed the platform, and deposed, in absentia, the man who would be king. And Minerva returned to the ocean

The story of Michael Oliver, his short-lived 1972 Republic of Minerva, and the response of the king of Tonga is not the stuff of fairy tales. Nor is it an uncommon story, an isolated event ripe for consumption as a chronicle of crazy rich Caucasians. In the U.S. after World War II, with the dramatic geopolitical changes wrought by decolonization and the Cold War, battles were waged over the meaning of ideals such as democracy and freedom, often pitting those who believed individual liberty to be more important than social equality against those who prioritized the latter over the former. In the midst of such struggles, individuals concerned with protecting their wealth, their safety, and their freedom from what they perceived to be an overbearing government and a threatening rabble sought to exit the U.S. and to establish their own independent, sovereign, and private countries on the ocean and in island spaces. It usually did not end well.

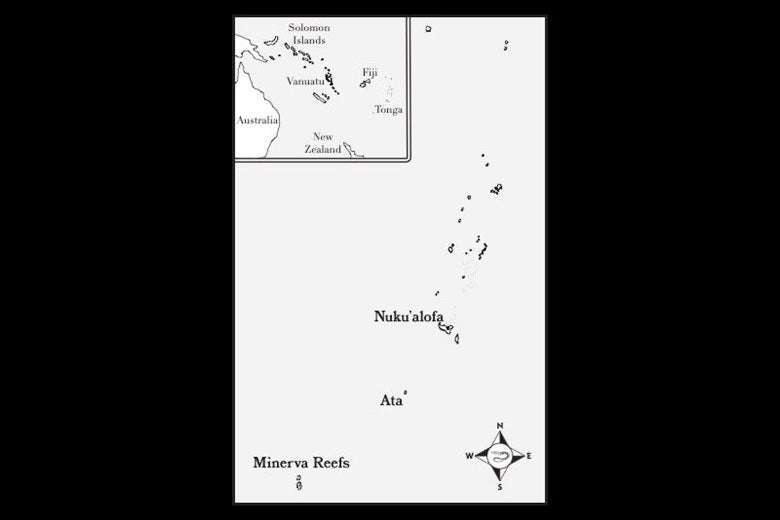

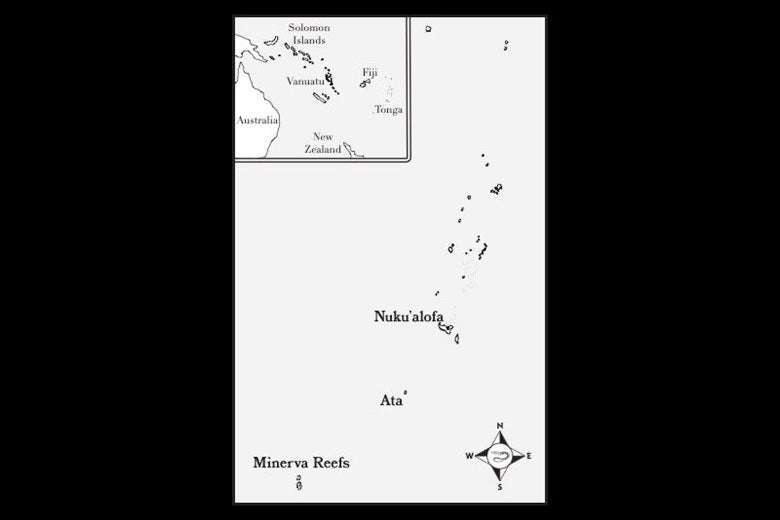

The location of the Minerva Reefs. John Wyatt Greenlee, copyright 2022

Experiments in libertarian exit—abandoning one’s country of residence for a private territory where social relationships are structured largely through contract and exchange—like the one Michael Oliver undertook were not unusual in the America of the 1960s and 1970s. They proved common enough that writers for the Los Angeles–based libertarian Innovator Magazine priced out the costs of various forms of exit, from “clandestine urban” and “underground shelter” to “sea-mobile nomad.” It was only a small step to imagine a commune on the high seas rather than in Northern California, or a private island in the Caribbean rather than a gated community in Orange County. Libertarian-inspired exit projects proliferated to the degree that one might recast the 1960s not as the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, but as the Age of Atlantis, the favored island reference point for libertarians.

The name itself was ubiquitous. The “Republic of New Atlantis” arose, albeit briefly, in 1964 when Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother Leicester parked an 8-by-30-foot bamboo raft, anchored to an old Ford engine block buried in the sand, 8 miles off the coast of Bluefields, Jamaica. He declared the birth of his new republic with a bottle of Seagram’s 7 in hand. Having encouraged birds to defecate on one end of the raft, he ceded that portion of it to the U.S. under the criteria established in the 1856 Guano Islands Act, which allowed citizens to claim possession of unoccupied islands, rocks, or keys that contained guano on behalf of the U.S. The raft’s other half became his own private country, albeit only briefly; a hurricane soon sank the vessel. Pharmaceutical engineer Werner Stiefel, whose family had fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, founded “Operation Atlantis” in 1968 in a motel next to I-87 in upstate New York. He recruited libertarian “immigrants” to collectively build a vessel that they would sail down the Hudson River to the Caribbean where they would establish a libertarian micronation. Like its namesake, it met a watery fate. Upon launch on the Hudson, the vessel capsized and caught fire. The Atlanteans, undeterred, repaired the ship and sailed it to the Bahamas, where it promptly sank during heavy weather.

A kind of iconoclastic curiosity could underpin some of these schemes, but it was more frequently unease and fear that drove exit projects. Apocalyptic scenarios of demographic, ecological, and monetary collapse proliferated in the 1960s, along with fears of nuclear annihilation. Works such as Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” were only the most prominent of a corpus of works that warned of an approaching disaster due to unchecked population growth and ostensibly unmanaged resources. Harry Harrison’s novel Make Room! Make Room! was reworked into the 1973 film Soylent Green, starring Charlton Heston as New York City detective Robert Thorn who, in the year 2022, discovers that the Soylent Corporation’s protein pills, allegedly created from ocean plankton, are made of human corpses. Ayn Rand and libertarian fellow travelers forecast monetary collapse due to government meddling, and encouraged listeners to instead invest in gold, a libertarian prediction and prescription that is now so often reused as to seem like parody. But just as prominent in the minds of exiters such as Michael Oliver as these apocalyptic concerns was a fear of social unrest and totalitarianism.

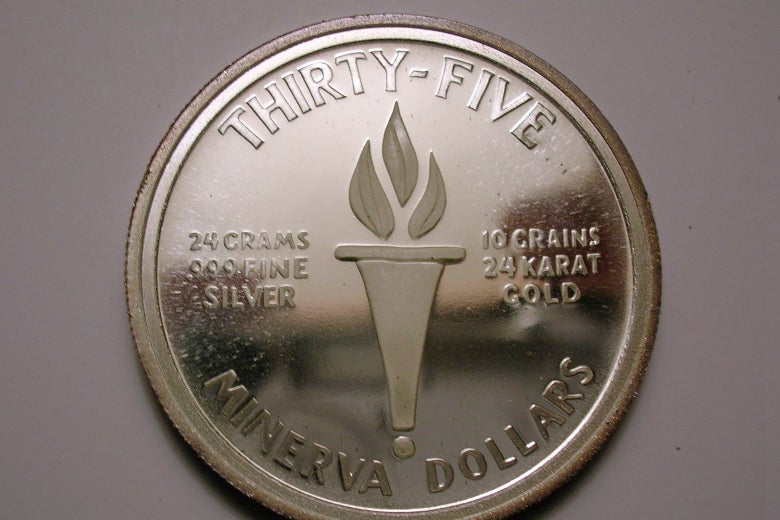

Born Moses Olitzky in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1928, Oliver had survived German massacres of Jews in his hometown, and then the Stutthof and Lager 10 concentration camps. Rescued by U.S. troops in 1945 while on a forced march from Dachau, he spent two years in a displaced persons camp before emigrating to the United States in 1947. His parents and four siblings all had been murdered. Once in the U.S., Olitzky changed his name to Michael Oliver and set roots down in Carson City, Nevada. He owned and operated a land development company as well as the Nevada Coin Exchange, specializing in the sale of gold and silver coins, which he advertised as security investments in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, and Innovator.

Over the course of the 1960s, Oliver became quite wealthy and began to translate that wealth into a hedge against a perceived rise of totalitarianism in the U.S., which he discerned in riots and protests around the country. Although he railed against “social meddlers” who opposed the free enterprise system and criticized how the government robbed society’s producers by creating welfare programs or pursuing inflationary policies and deficit spending, it was the masses and their supposed susceptibility to demagoguery that most concerned him. While he could have identified the populist, often apocalyptic and violent, politics of the right—the John Birchers and the Minutemen, the Ku Klux Klan and the Christian anti-Communist crusaders—as the existential threat, it was populations acting in the name of “liberalism” and “freedom now” whom he accused of employing “Storm Trooper tactics.” His libertarianism dovetailed with the socially conservative property-rights movement that took shape around Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential candidacy, and has grown ever more potent in recent decades.

Experiments in libertarian exit—abandoning one’s country of residence for a private territory where social relationships are structured largely through contract and exchange—like the one Michael Oliver undertook were not unusual in the America of the 1960s and 1970s. They proved common enough that writers for the Los Angeles–based libertarian Innovator Magazine priced out the costs of various forms of exit, from “clandestine urban” and “underground shelter” to “sea-mobile nomad.” It was only a small step to imagine a commune on the high seas rather than in Northern California, or a private island in the Caribbean rather than a gated community in Orange County. Libertarian-inspired exit projects proliferated to the degree that one might recast the 1960s not as the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, but as the Age of Atlantis, the favored island reference point for libertarians.

The name itself was ubiquitous. The “Republic of New Atlantis” arose, albeit briefly, in 1964 when Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother Leicester parked an 8-by-30-foot bamboo raft, anchored to an old Ford engine block buried in the sand, 8 miles off the coast of Bluefields, Jamaica. He declared the birth of his new republic with a bottle of Seagram’s 7 in hand. Having encouraged birds to defecate on one end of the raft, he ceded that portion of it to the U.S. under the criteria established in the 1856 Guano Islands Act, which allowed citizens to claim possession of unoccupied islands, rocks, or keys that contained guano on behalf of the U.S. The raft’s other half became his own private country, albeit only briefly; a hurricane soon sank the vessel. Pharmaceutical engineer Werner Stiefel, whose family had fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, founded “Operation Atlantis” in 1968 in a motel next to I-87 in upstate New York. He recruited libertarian “immigrants” to collectively build a vessel that they would sail down the Hudson River to the Caribbean where they would establish a libertarian micronation. Like its namesake, it met a watery fate. Upon launch on the Hudson, the vessel capsized and caught fire. The Atlanteans, undeterred, repaired the ship and sailed it to the Bahamas, where it promptly sank during heavy weather.

A kind of iconoclastic curiosity could underpin some of these schemes, but it was more frequently unease and fear that drove exit projects. Apocalyptic scenarios of demographic, ecological, and monetary collapse proliferated in the 1960s, along with fears of nuclear annihilation. Works such as Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” were only the most prominent of a corpus of works that warned of an approaching disaster due to unchecked population growth and ostensibly unmanaged resources. Harry Harrison’s novel Make Room! Make Room! was reworked into the 1973 film Soylent Green, starring Charlton Heston as New York City detective Robert Thorn who, in the year 2022, discovers that the Soylent Corporation’s protein pills, allegedly created from ocean plankton, are made of human corpses. Ayn Rand and libertarian fellow travelers forecast monetary collapse due to government meddling, and encouraged listeners to instead invest in gold, a libertarian prediction and prescription that is now so often reused as to seem like parody. But just as prominent in the minds of exiters such as Michael Oliver as these apocalyptic concerns was a fear of social unrest and totalitarianism.

Born Moses Olitzky in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1928, Oliver had survived German massacres of Jews in his hometown, and then the Stutthof and Lager 10 concentration camps. Rescued by U.S. troops in 1945 while on a forced march from Dachau, he spent two years in a displaced persons camp before emigrating to the United States in 1947. His parents and four siblings all had been murdered. Once in the U.S., Olitzky changed his name to Michael Oliver and set roots down in Carson City, Nevada. He owned and operated a land development company as well as the Nevada Coin Exchange, specializing in the sale of gold and silver coins, which he advertised as security investments in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, and Innovator.

Over the course of the 1960s, Oliver became quite wealthy and began to translate that wealth into a hedge against a perceived rise of totalitarianism in the U.S., which he discerned in riots and protests around the country. Although he railed against “social meddlers” who opposed the free enterprise system and criticized how the government robbed society’s producers by creating welfare programs or pursuing inflationary policies and deficit spending, it was the masses and their supposed susceptibility to demagoguery that most concerned him. While he could have identified the populist, often apocalyptic and violent, politics of the right—the John Birchers and the Minutemen, the Ku Klux Klan and the Christian anti-Communist crusaders—as the existential threat, it was populations acting in the name of “liberalism” and “freedom now” whom he accused of employing “Storm Trooper tactics.” His libertarianism dovetailed with the socially conservative property-rights movement that took shape around Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential candidacy, and has grown ever more potent in recent decades.

Roger Griffith/Wikimedia Commons

Roger Griffith/Wikimedia Commons

Oliver ignored calls to stay put and fight for liberty at home. Instead, he sought to escape what he saw as the approaching storm of social unrest and revolution by creating a new country. Its structure he outlined in a self-published 1968 book, A New Constitution for a New Country. Oliver crafted his constitution for an imagined libertarian territory freed from bureaucratic constraints and the regulatory apparatus of the welfare state. The book contained a declaration of purpose, a plan of action, and a constitution with 11 articles. Oliver designed the constitution as an improved version of the United States Constitution—improved in that it would “spell out the details whereby government can, at the same time, properly protect persons from force and fraud and also be prevented from exceeding this only legitimate function.” The argument that the sole function of government is to protect individuals from force and fraud echoed mainstream libertarian thinking of the time, found in the work of novelist Ayn Rand, economists Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises, and philosopher Robert Nozick. Although its proponents describe the ideal government as a “nightwatchman” or “ultra-minimalist” state, it would be a mistake to understand this as a call for a smaller state. Its minimalism had little to do with the size of its apparatus or budget, but rather with the limitations placed on the range of its functions: national defense, policing, and a legal infrastructure dedicated to the protection of property rights and enforcement of contract.

Published in February of 1968, Oliver’s book sold out quickly, and a second edition appeared in May of that same year. Admiring readers found the book via word of mouth and advertisements in libertarian magazines and soon convinced others of Oliver’s vision. Among these acolytes were Wichita wheat magnate and World Homes chief executive Willard Garvey, millionaire horologist Seth Atwood, famed banker and fund manager John Templeton, and former placekicker for the undefeated 1954 Ohio State football team (and inventor of the eponymous WEED tennis racquet) Tad Weed. They helped bankroll efforts to put Oliver’s new country idea into action through his Ocean Life Research Foundation.

The foundation’s name is revealing. In order to build a self-governing, private territory in which the very promises of libertarian theory could be fulfilled, Oliver required a locale not already under the sovereign control of another state, or that a state would be willing to sell for such purposes. In the high era of decolonization—between 1945 and 1960 alone, the number of nation-states represented in the United Nations doubled, and over the course of the 1960s grew further due to decolonization in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific—Oliver seemed assured that he could find a government with which to negotiate. “A surprising number of nearly uninhabited, yet quite suitable places for establishing a new country still exist,” he informed readers of his Capitalist Country Newsletter in 1968. “Many such places are scarcely developed colonies whose governmental or other activities are of little or no concern at all to their ‘mother’ countries. There will be little problem in purchasing the land, or in having the opportunity to conduct affairs on a free enterprise basis from the very beginning.”

This was an optimistic evaluation, as Oliver would repeatedly learn in the coming decade. Between 1968 and 1971 alone, he or his associates made exploratory visits to the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Curaçao, Suriname, New Caledonia, French Guiana, Honduras, and New Hebrides to gather information on climate, taxation, and land quality and to explore the possibilities of building a libertarian country. Such visits revealed the difficulties confronting any would-be world builder looking to land on distant shores. Purchasing land was no problem. But purchasing sovereignty was. And so his first real effort unfolded on a space long seen as open: the ocean.

Oliver ignored calls to stay put and fight for liberty at home. Instead, he sought to escape what he saw as the approaching storm of social unrest and revolution by creating a new country. Its structure he outlined in a self-published 1968 book, A New Constitution for a New Country. Oliver crafted his constitution for an imagined libertarian territory freed from bureaucratic constraints and the regulatory apparatus of the welfare state. The book contained a declaration of purpose, a plan of action, and a constitution with 11 articles. Oliver designed the constitution as an improved version of the United States Constitution—improved in that it would “spell out the details whereby government can, at the same time, properly protect persons from force and fraud and also be prevented from exceeding this only legitimate function.” The argument that the sole function of government is to protect individuals from force and fraud echoed mainstream libertarian thinking of the time, found in the work of novelist Ayn Rand, economists Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises, and philosopher Robert Nozick. Although its proponents describe the ideal government as a “nightwatchman” or “ultra-minimalist” state, it would be a mistake to understand this as a call for a smaller state. Its minimalism had little to do with the size of its apparatus or budget, but rather with the limitations placed on the range of its functions: national defense, policing, and a legal infrastructure dedicated to the protection of property rights and enforcement of contract.

Published in February of 1968, Oliver’s book sold out quickly, and a second edition appeared in May of that same year. Admiring readers found the book via word of mouth and advertisements in libertarian magazines and soon convinced others of Oliver’s vision. Among these acolytes were Wichita wheat magnate and World Homes chief executive Willard Garvey, millionaire horologist Seth Atwood, famed banker and fund manager John Templeton, and former placekicker for the undefeated 1954 Ohio State football team (and inventor of the eponymous WEED tennis racquet) Tad Weed. They helped bankroll efforts to put Oliver’s new country idea into action through his Ocean Life Research Foundation.

The foundation’s name is revealing. In order to build a self-governing, private territory in which the very promises of libertarian theory could be fulfilled, Oliver required a locale not already under the sovereign control of another state, or that a state would be willing to sell for such purposes. In the high era of decolonization—between 1945 and 1960 alone, the number of nation-states represented in the United Nations doubled, and over the course of the 1960s grew further due to decolonization in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific—Oliver seemed assured that he could find a government with which to negotiate. “A surprising number of nearly uninhabited, yet quite suitable places for establishing a new country still exist,” he informed readers of his Capitalist Country Newsletter in 1968. “Many such places are scarcely developed colonies whose governmental or other activities are of little or no concern at all to their ‘mother’ countries. There will be little problem in purchasing the land, or in having the opportunity to conduct affairs on a free enterprise basis from the very beginning.”

This was an optimistic evaluation, as Oliver would repeatedly learn in the coming decade. Between 1968 and 1971 alone, he or his associates made exploratory visits to the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Curaçao, Suriname, New Caledonia, French Guiana, Honduras, and New Hebrides to gather information on climate, taxation, and land quality and to explore the possibilities of building a libertarian country. Such visits revealed the difficulties confronting any would-be world builder looking to land on distant shores. Purchasing land was no problem. But purchasing sovereignty was. And so his first real effort unfolded on a space long seen as open: the ocean.

“There will be little problem in purchasing the land, or in having the opportunity to conduct affairs on a free enterprise basis from the very beginning.”— Michael Oliver, founder of the Republic of Minerva

That oceans and islands have figured prominently in exit efforts should come as no surprise. Both have long constituted spaces upon which to situate arguments and plot fantasies about the market, exchange, politics, and society. It was under the ocean (not upon it) that Captain Nemo, antihero of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, sought to escape the tyranny of nation-states. On the ocean proved as appealing as under it. In one of his less well-known works, The Self-Propelled Island, Verne described the geography of the island Pacific by using as his primary narrative device a large, artificial floating island inhabited solely by bickering billionaires—a prescient vision of 21st century seasteading. The high seas were and are still frequently invoked, even if mistakenly, as spaces of nonsovereignty and lawlessness, the last great frontier for those seeking freedom from the state, whether it be to profit through illegal fishing and exploitation of labor or to experiment with new forms of political and social life.

Similarly, “remote” and small islands have provided a place for imaginative experiments in political, legal, and social engineering, from Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis and Thomas More’s Utopia to H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. As clearly defined, circumscribed territorial entities, small islands can seem like natural laboratories in which political and social experiments can unfold without the noise of contingency, the burden of history, or the taint of politics. Given that one of classical liberalism’s founding myths, Robinson Crusoe, grew out of the fertile soil of a distant archipelago, it is not surprising how much islands figure in libertarian exit fantasies. Alexander Selkirk’s four-and-a-half-year struggle as a castaway isolated on the Juan Fernández Islands off the coast of Chile served as the historical basis for Daniel Defoe’s novel, a story that made remote islands an ideal libertarian political ecology: an overdetermined geographic form upon which the drama of individualism, of man alone, could be staged.

Islands and ocean spaces have been attractive not only because they are conceived of as laboratory spaces but also because they are very often sites that seem ripe for speculation and planning for new countries. In the post–World War II world, many island territories were the last to decolonize. Much of the Pacific remained under colonial control into the 1970s, and a significant portion still exists somewhere between dependence and independence. Such political opacity and geopolitical vulnerability made them attractive locations for those looking to get some territorial purchase on their libertarian dreams.

By 1971, Garvey, Atwood, Oliver, and their associates had set their sights on the Minerva Reefs. They did so after having rejected the option of another southwest Pacific atoll, the Conway Reef, when they learned that an Australian consortium intended to develop it for the construction of a casino. The Minerva Reefs were more attractive. They seemed to sit within neither the territorial waters of Aotearoa New Zealand to the south, nor Fiji or Tonga to the north. In August 1971, the Ocean Life Research Foundation arrived at the Minerva Reefs and began the arduous process of building an island in the southwest Pacific. A dredging vessel piled sand on the reef, while a small crew erected two mounds made from coral wrapped in chicken wire and encased in concrete, upon which they then constructed 26-foot vertical markers topped by a flag representing the Republic of Minerva.

These steps laid the groundwork for the new country, which would operate as an offshore financial center and house 30,000 settlers. Funds for the country came from settlers who would pay a base rate for a 3-acre plot of land, and from investors who, rather than settle in Minerva, would back the project and share in the profits. A corporation and board of directors would steer the process and review every settler application. “Capability of self-support,” Oliver wrote, “or sufficient assets shall be one of the requirements for acceptance.” Other conditions also applied: “collectivists […] criminals, nihilists, or anarchists” would not be welcome, regardless of their purchasing power.

Anarchists and nihilists turned out to be the least of their worries.

By early 1972, the king of Tonga, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV, had caught wind of the project, and began to voice concerns. The Minerva Reefs may have sat at a substantial distance from the core of the Tongan archipelago and beyond its territorial waters, but that hardly meant they were not a part of Tonga’s political and cultural horizon. The reefs had long served as seasonal lobstering and fishing grounds for Tongans and Fijians. Historical and human connections to the reefs ran deep.

Anarchists and nihilists turned out to be the least of their worries.

One incident in particular tied Tonga and the reefs together. In 1962, the Tuaikaepau, a 50-foot, 20-ton cutter bound for Aotearoa New Zealand from Tonga, struck the northwestern edge of South Minerva Reef. Capt. Tevita Fifita, the crew, and the passengers—all Tongan and all of whom survived the initial impact and a night struggling with the thunderous high tide—knew they were in serious trouble. Far from shipping lanes and subject to the cold winds that blew north from Antarctica across the Tasman Sea, the Minerva Reefs saw visitors infrequently. For three months the group struggled, holed up in the shell of a rusting Japanese fishing vessel that had foundered on the reefs two years earlier. They survived on fish, crayfish, and the small amounts of water they could either produce with a homemade still or catch from infrequent rains. Most of them suffered from various ailments, and in early October, in the span of only two days, three men died. The men buried the body of the first person to die in the reef. They wrapped his body in layers of canvas to protect it from crabs and fish. They marked the grave with a cross. Soon after, Fifita made the decision to build an outrigger canoe from the remains of available wreckage, and, along with his son and the ship’s carpenter, they paddled to Kadavu, Fiji, where their vessel capsized while attempting to navigate the reefs. Fifita’s son drowned. The remainder of the rescue party succeeded in reaching help.

Tongans mourned the tragedy and celebrated the rescue. Queen Sālote declared a national holiday and wrote a poem in the crew’s honor. The Minerva Reefs became indelibly attached to the memory of Tuaikaepau and the history of its crew and passengers. In 1966, Fifita returned to the reefs and attached a Tongan flag to a buoy there, an act that took on the important appearance of a ceremony of annexation. Then, in 1972, conflict with the Ocean Life Research Foundation erupted. As word of the exiters’ activities spread, King Tupou began investigating. In February 1972, he sent a fact-finding mission to the reefs. The participants established a refuge station on the South Minerva Reef, but the king’s government made no immediate claim of possession or sovereignty. In May, he himself sailed to the reefs with the brass band and freed convicts accompanying him. He ordered the building of a structure on each reef that would remain permanently above the high-water mark. The king then used these built structures as the basis for a claim of possession on June 15, 1972.

The king’s assertion of sovereignty had the potential to stoke conflicts, particularly with neighboring Fiji, but at the intergovernmental 1972 South Pacific Forum meeting, convened for Southwest Pacific trade discussions and cooperation, heads of state from Fiji, Nauru, Western Samoa, and the Cook Islands agreed that Tonga had a long-standing historical association with the reefs, and that any other claim to sovereignty, and in particular “that of the Ocean Life Research Foundation,” was unacceptable. The king could count on regional support from other heads of state because they, too, feared that any successful libertarian colonization would open up dozens of Southwestern Pacific seamounts and atolls to claims of ownership. The question reached well beyond the bounds of one nation. As Oceanian decolonization proceeded, questions of archipelagic territorial rights to the ocean—never adequately addressed in early U.N. conferences on the sea—arose and led to the writing over the course of the 1970s of a series of Archipelagic Provisions that would be adopted at the 1982 Conference on the Law of the Sea. Such provisions accentuated what islanders themselves had long understood: that the ocean was a human space.

Oliver and his backers withdrew. For the founders of the Republic of Minerva, the reefs were a space of legal liminality, one of the few areas where establishing a new country seemed possible. With terra firma firmly divided among nation-states, the oceans seemed to be the only empty spaces left. Yet, as has so often been the case, spaces perceived by distant colonizers as open for the taking are in fact places that sit within the social and cultural horizon of nearby peoples. For Tongans, the reefs were part of a history of navigation and settlement, of rescue and loss, of meaning and mourning, and part of a geography of identity and livelihood where sea and land entwined. Rather than distant atolls, they were places of provision and poetry and history. No doubt one day, maybe a thousand years hence, a natural island will come to be in Minerva, a result of processes of the kind that had built up the reefs themselves. But not until then. The only invisible hand at work among the atolls and seamounts of the Native Pacific will be that of the ocean.

Adventure Capitalism: A History of Libertarian Exit, From the Era of Decolonization to the Digital Age

By Raymond B. Craib. PM Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment