Macro portraits reveal the glamor and peril of endangered insects

Photographer Levon Biss captures the exquisite majesty of bugs—and the pressures that threaten them.

BY LAUREN J. YOUNG | PUBLISHED JUN 28, 2022

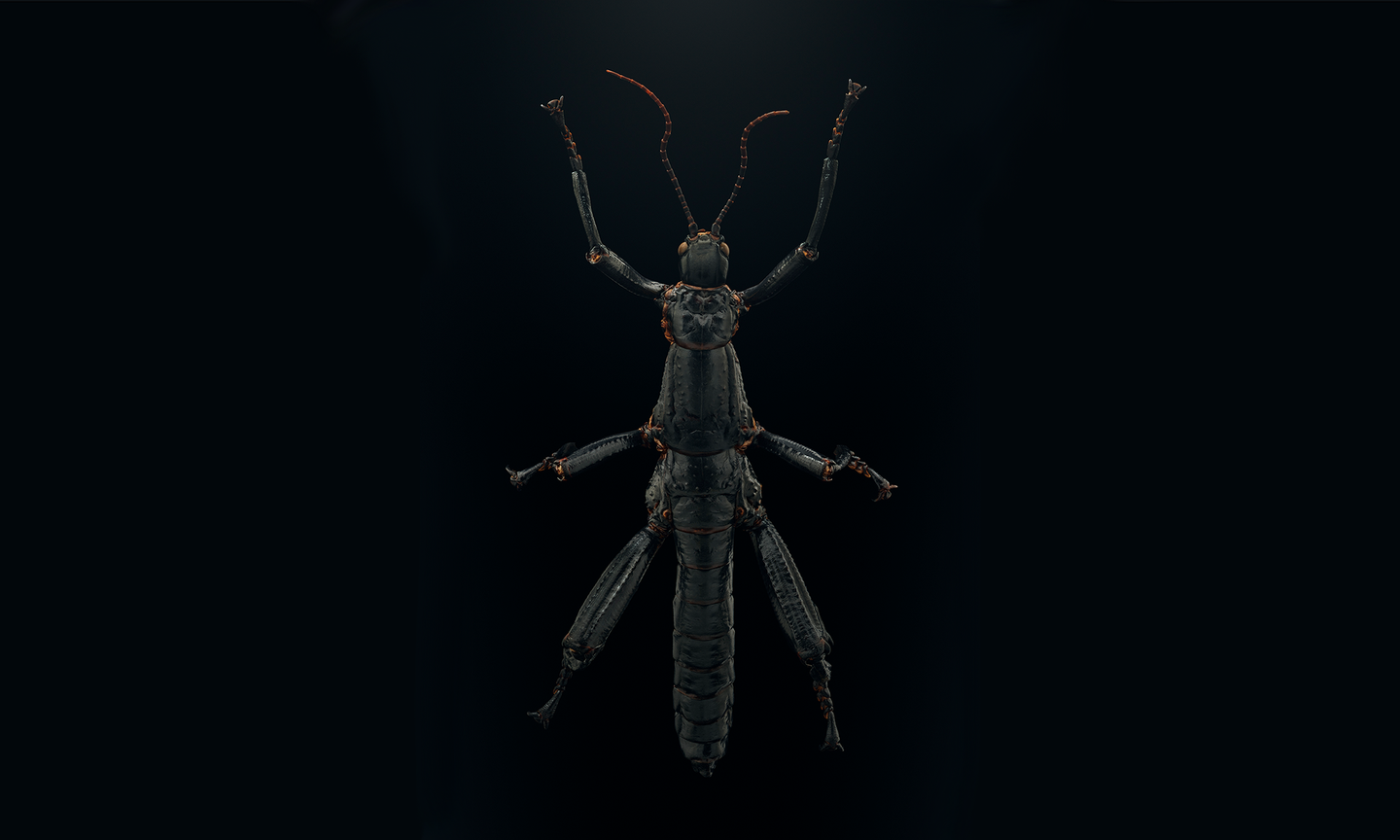

This large stick bug, up to seven inches long, might seem hard to miss in the wild, but the insect slips under the radar, resembling lichens and leaves. Levon Biss

The Lord Howe Island stick insect might look more lobster than bug. Nicknamed the “land lobster,” this critter can grow up to seven inches long and gleams like polished obsidian among tree trunks and twigs, blending into the forest environment. For decades, Lord Howe Island, a small volcanic isle just northeast of Sydney, Australia, was the only known home of the species, Dryococelus australis. But in 1918, a shipwreck introduced predatory black rats that decimated the stick bug and many other native animals. Locals and biologists thought the insect was extinct until 2001, when a tiny population was discovered on a small nearby spired island, Ball’s Pyramid. Zoo and museum scientists are breeding the insects to restore this once-lost species and soon return it back to the wild—their original home on Lord Howe Island.

The Lord Howe Island stick insect represents one of 40 species brought to life in a new macrophotography exhibit, Extinct and Endangered: Insects in Peril, by photographer Levon Biss at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The large format photos not only reveal the insects’ diverse textures and minute hairs in vivid detail—they also shed light on these often overlooked creatures whose existence is threatened by human-induced climate change and other ongoing pressures.

“Right now, we’re just in the process of trying to quantify how much insects are in trouble,” says David Grimaldi, the museum’s invertebrate zoologist who curated the exhibit, in a video. “We have to rely on entomologists and other biologists to go out into the field and monitor insects, but we shouldn’t wait for the counts. We should start protecting natural areas.”

[Related: Do we still need to save the bees?]

Insects make up 80 percent of animal life on Earth, shaping a significant slice of our ecosystem from pollinating crops to decomposing waste. In 2017, a study in PLOS One revealed that more than 75 percent of the total biomass of flying insects in protected nature reserves in Germany had been lost over 27 years—scratching just the surface of an alarming trend of species diversity loss and insect population decline.

“Without hyperbole we’re in a very serious conundrum,” says Jessica Ware, entomologist and associate curator in invertebrate zoology at the museum, in AMNH’s press video. “Insects have undergone mass extinctions in the past, but right now the mass extinction that we’re seeing, that we’re witnessing, seems to be the largest that’s ever been recorded.”

With the power of macrophotography, Biss hopes that the insect portraits of Extinct and Endangered: Insects in Peril will be an eye-opening look at insects that showcases both their beauty and their value. These tiny creatures, Biss says in the video, go underappreciated despite being so important to humans and the planet.

“We need to understand that they’re important and we can’t just ignore them because they’re hard to see,” Biss says. “Hopefully people will walk away with an appreciation of them and they’ll marvel in them, and realize that they’re too beautiful to be lost, they’re too important to be lost.”

Images and specimen captions from Endangered: Insects in Peril are provided by AMNH.

Sabertooth longhorn beetle. Levon Biss

The sabertooth longhorn beetle, Macrodontia cervicornis, lives in the Amazon River basin and is among the longest beetles in the world. Habitat loss has contributed to its vulnerable status. The practice of collecting and selling these beetles—a single specimen can go for thousands of dollars—is another cause of their decline.

The sabertooth longhorn beetle, Macrodontia cervicornis, lives in the Amazon River basin and is among the longest beetles in the world. Habitat loss has contributed to its vulnerable status. The practice of collecting and selling these beetles—a single specimen can go for thousands of dollars—is another cause of their decline.

Stygian shadowdragon. Levon Biss

Dragonflies may be the most acrobatic fliers in the insect world, and stygian shadowdragons are no exception. Late in the twilight, they soar high above dark waters, swooping down to capture mosquitoes and other insect prey. Living near lakes and rivers in the eastern US and Canada, stygian shadowdragons, Neurocordulia yamaskanensis, start out life in the water. Females lay their eggs and larvae develop there, breathing through internal gills.

[Related: Inflatable tentacles and silk hats: See how caterpillars trick predators to survive]

For now, their numbers appear stable in some parts of their range, but in other areas they have completely disappeared. In coming years, climate change could have many detrimental effects on remaining populations. Much remains to be learned about how dragonfly larvae manage in northeastern rivers and lakes, and if those waters warm dramatically, the larvae may not be able to survive. Depending on how the waters are affected by heat, drought and other factors such as water pollution, researchers have estimated that more than 50 percent of this dragonfly species’ preferred river habitat could be lost as the climate shifts.

Dragonflies may be the most acrobatic fliers in the insect world, and stygian shadowdragons are no exception. Late in the twilight, they soar high above dark waters, swooping down to capture mosquitoes and other insect prey. Living near lakes and rivers in the eastern US and Canada, stygian shadowdragons, Neurocordulia yamaskanensis, start out life in the water. Females lay their eggs and larvae develop there, breathing through internal gills.

[Related: Inflatable tentacles and silk hats: See how caterpillars trick predators to survive]

For now, their numbers appear stable in some parts of their range, but in other areas they have completely disappeared. In coming years, climate change could have many detrimental effects on remaining populations. Much remains to be learned about how dragonfly larvae manage in northeastern rivers and lakes, and if those waters warm dramatically, the larvae may not be able to survive. Depending on how the waters are affected by heat, drought and other factors such as water pollution, researchers have estimated that more than 50 percent of this dragonfly species’ preferred river habitat could be lost as the climate shifts.

Raspa silkmoth. Levon Biss

The raspa silkmoth, Sphingicampa raspa, lives in hot, arid areas of Arizona, West Texas, and in Mexico, and depends on the “monsoon” season as part of its life cycle. If these reliable yearly rainstorms are affected by climate change, it could imperil these and other southwestern moths and butterflies.

The raspa silkmoth, Sphingicampa raspa, lives in hot, arid areas of Arizona, West Texas, and in Mexico, and depends on the “monsoon” season as part of its life cycle. If these reliable yearly rainstorms are affected by climate change, it could imperil these and other southwestern moths and butterflies.

Coral pink sand dunes tiger beetle, Cicindela albissima.

Levon Biss

This colorful tiger beetle may look flashy, but in the pink sand dunes of its Utah habitat, its cream and green hues actually help the animal blend in. The cream forewings also help these beetles handle desert heat, by reflecting rather than absorbing sunlight. In the dunes, these tiger beetles are predators—note the insect’s curving mandibles, used to capture ants, flies, and other small prey.

The beetles’ tiny range lies on public lands, and researchers and wildlife officials there have closely monitored them for years. In low-rainfall years they have found the beetle population falls—a decline that may only become steeper with climate change. A different type of risk comes from people driving off-road vehicles over the dunes. To prevent the larvae in their burrows from being crushed, officials have set aside some conservation areas where the vehicles are now prohibited.

This colorful tiger beetle may look flashy, but in the pink sand dunes of its Utah habitat, its cream and green hues actually help the animal blend in. The cream forewings also help these beetles handle desert heat, by reflecting rather than absorbing sunlight. In the dunes, these tiger beetles are predators—note the insect’s curving mandibles, used to capture ants, flies, and other small prey.

The beetles’ tiny range lies on public lands, and researchers and wildlife officials there have closely monitored them for years. In low-rainfall years they have found the beetle population falls—a decline that may only become steeper with climate change. A different type of risk comes from people driving off-road vehicles over the dunes. To prevent the larvae in their burrows from being crushed, officials have set aside some conservation areas where the vehicles are now prohibited.

17-year cicada. Levon Biss

Every 17 years when the weather warms, millions of periodical cicadas (Magicicada septendecim) have a mass emergence, digging themselves out of the soil where they’ve been growing, climbing up trees, and splitting out of their skins into winged adults. But land clearing and development may destroy the underground nymphs before they can emerge and reproduce. And pesticides applied to lawns, golf courses, and parks seep into the ground where the nymphs feed.

Every 17 years when the weather warms, millions of periodical cicadas (Magicicada septendecim) have a mass emergence, digging themselves out of the soil where they’ve been growing, climbing up trees, and splitting out of their skins into winged adults. But land clearing and development may destroy the underground nymphs before they can emerge and reproduce. And pesticides applied to lawns, golf courses, and parks seep into the ground where the nymphs feed.

Lauren J. Young is an Associate Editor at Popular Science where she covers health inequities, environmental justice, biodiversity, space exploration, history, and culture. Before joining PopSci in 2021, she was a digital producer and reporter at public radio’s Science Friday. Contact the author here.

No comments:

Post a Comment