There is no court legitimacy without public trust in the court.

SLATE

JUNE 24, 2022

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Brad Weaver/Unsplash and 101cats/Getty Images Plus.

A few short weeks ago, speaking at a Federalist Society event, Justice Clarence Thomas warned ominously that “you cannot have a free society” without stable institutions. He contended that “we should be careful destroying our institutions because they don’t give us what we want when we want.” In hindsight his prediction that public regard for institutions—his worry that he didn’t know how much longer we would have and keep those institutions—reads more like a ransom note than a lament.

What Thomas was telling us was that institutional respect is owed, blindly and without conditions. It chimed in the same key as then–Attorney General Bill Barr’s promise that unless Americans stopped disrespecting the police, the police might stop showing up to protect them. That isn’t how respect, or public trust, works. Those things are earned, over time. They can also be squandered, we are now learning, in the span of a few careless months.

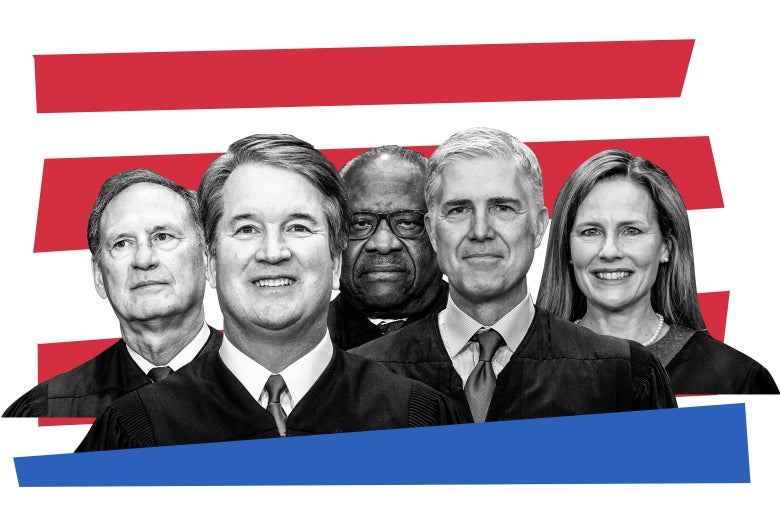

Today, for the first time in constitutional history, the United States Supreme Court, by a 6–3 margin, took a fundamental constitutionally protected right away from half the population, a right around which generations of women and families have ordered their lives. Make no mistake, the same court that just 24 hours earlier had determined that the decision to carry a gun on the streets is such an essential aspect of personal liberty that states may not be permitted to regulate it has now declared that decisions about abortion, miscarriage, contraception, economic survival, child-rearing, and intimate family matters are worthy of zero solicitude. None. In their view of liberty, women were worthy of zero solicitude at the founding, and remain unworthy of it today. As Mark Joseph Stern notes, women will suffer. Some will be refused treatment for miscarriages, and some will be turned away from emergency rooms. Some will be hunted down, spied on, and prosecuted for seeking health care, medication, and autonomy. The majority glibly tells us that because the harms to these people are unknowable, they are not urgent—or at the very least, less urgent than the harms faced by people who would like to see more guns in public spaces.

But ordinary Americans do not think these harms are trivial. On Thursday, Gallup polling showed public approval for the Supreme Court to be at a historic low—25 percent. It’s a precipitous drop from the prior historic low the court received in September, which sat at about 38 percent. The six justices in the majority of Dobbs will comfort themselves that this doesn’t matter. They will tell themselves that they corrected a historical injustice and that they saved unborn babies. They will say that they have lifetime tenure in order to protect against the whims of the majorities. They will blame protesters and they will continue to blame the press. Even the much-vaunted centrism and pragmatism of Chief Justice John Roberts seems to have left the building. Notwithstanding the fact of his seemingly moderate concurrence—in joining with a majority that could not wait to do in three years what they could do in one—it is clear that he has lost his court, and that he is surely less worried about the public regard for the institution than we had believed.

The joint dissent, authored together by Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor, is elegiac in tone. It includes a shoutout to the three Republican appointees who crossed the partisan line to preserve Roe in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey—not because they liked abortion but because, as they write, they chose to privilege the legitimacy of the institution over their personal wants. Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor wrote of the triumvirate that came before them, and of their unwillingness to harm the standing of the institution they loved:

“[T]he Court,” Casey explained, “could not pretend” that overruling Roe had any “justification beyond a present doctrinal disposition to come out differently from the Court of 1973…. To reverse prior law “upon a ground no firmer than a change in [the Court’s] membership”— would invite the view that “this institution is little different from the two political branches of the Government.” No view, Casey thought, could do “more lasting injury to this Court and to the system of law which it is our abiding mission to serve. For overruling Roe, Casey concluded, the Court would pay a “terrible price.”

The dissent laments the loss of Souter, O’Connor, and Kennedy as “judges of wisdom.” The three write, “They knew that ‘the legitimacy of the Court [is] earned over time.’ ” They also would have recognized that it can be destroyed much more quickly. Quoting Breyer’s recent lament that “it is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much,” the three dissenters conclude: “For all of us, in our time on this Court, that has never been more true than today.”

Compare this to Justice Samuel Alito’s flippant dismissal of the pain soon to be heaped upon the court, the country, women, their children, and families, pain that is laid out in one meticulous amicus brief after the next:

We do not pretend to know how our political system or society will respond to today’s decision overruling Roe and Casey. And even if we could foresee what will happen, we would have no authority to let that knowledge influence our decision. We can only do our job, which is to interpret the law, apply longstanding principles of stare decisis, and decide this case accordingly.

It is one thing to take away autonomy and dignity. It’s something else entirely to say that the hardship and jolt to the nation cannot be determined, and shouldn’t even matter.

The three dissenters take no joy in decrying the self-administered body blow the court has brought upon itself this term. There is no pleasure in seeing new fencing around the building, nor is there any delight in the protesters blocking D.C. streets or staking out justices’ residences. There is no mention of the fact that one of their colleagues is married to a partisan political operator who worked to support those who would have set aside the presidential election. There is simply the acceptance of that colleague’s abject refusal to take responsibility for it. This may well be one of the last published opinions of Stephen Breyer’s storied legal career, and it reads like a rebuke to his own aspirational hopes, including in a book published only this fall, for an institution he tried to protect until the end. Breyer always understood that public acceptance and regard aren’t demanded, and that for the court he is departing, it may not come back.

The dissenters understand where to place the blame for this loss of legitimacy. Even in the notoriously collegial Supreme Court, they place it squarely, and fairly, on a majority that has spent a year proving itself unwilling to moderate tone, language, conduct, and pace in exchange for the appearance of sobriety. The “stench,” as Sotomayor once warned, will not dissipate just because the majority can’t smell it.

The Supreme Court’s Conservatives Are Absolute Weasels

My Boyfriend Recently Introduced Me to His Family. Turns Out I Already, Uh, “Knew” His Brother.

One Story That Shows Amy Coney Barrett’s “Plan” for Abortion Isn’t One at All

There will not be a glorious peace that settles over the land now that this issue has been sent back to the states, no matter how much Justice Brett Kavanaugh wants you to believe it. There will be infighting among states, and vicious criminal prosecutions, and joyous theological efforts to secure future harms for gay partners and families struggling with IVF and women seeking contraception. The people who suffer the most will be the poorest, the youngest, the sickest—the people whose interests don’t even warrant acknowledgment by the majority opinion.

The dissenters sign off in “sorrow.” It is a sentiment that is surely directed at millions of women who will suffer appallingly as a result of this ruling. But it is also sorrow for an institution that was always rooted in an idea that there had to be a relationship between the public trust and judicial power. Justices are not kings. They can demand silent reverence, but it is not assured them. There have been plenty of us warning that this relationship was in jeopardy for many years, and the warnings were dismissed as efforts to undermine the court. Today’s decision confirms that, if and when the public is finally ready to give up on the court, there will be nobody to blame but the six justices who gave them nothing to believe in.

Read more of Slate’s coverage on abortion rights here.

A few short weeks ago, speaking at a Federalist Society event, Justice Clarence Thomas warned ominously that “you cannot have a free society” without stable institutions. He contended that “we should be careful destroying our institutions because they don’t give us what we want when we want.” In hindsight his prediction that public regard for institutions—his worry that he didn’t know how much longer we would have and keep those institutions—reads more like a ransom note than a lament.

What Thomas was telling us was that institutional respect is owed, blindly and without conditions. It chimed in the same key as then–Attorney General Bill Barr’s promise that unless Americans stopped disrespecting the police, the police might stop showing up to protect them. That isn’t how respect, or public trust, works. Those things are earned, over time. They can also be squandered, we are now learning, in the span of a few careless months.

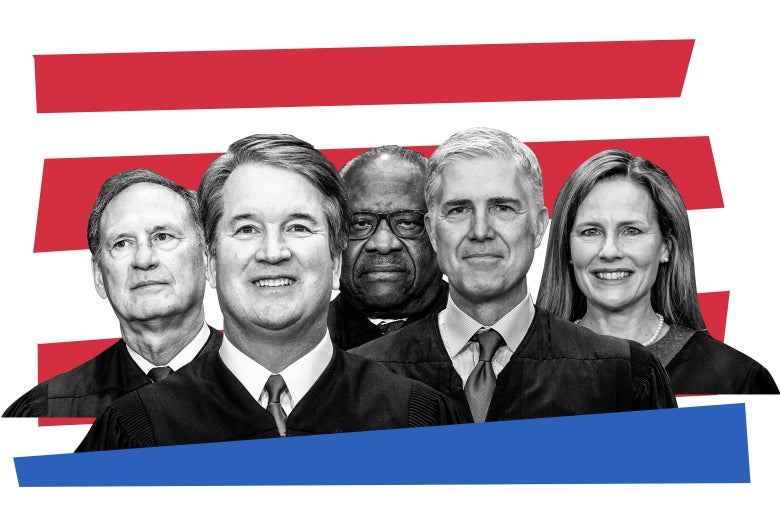

Today, for the first time in constitutional history, the United States Supreme Court, by a 6–3 margin, took a fundamental constitutionally protected right away from half the population, a right around which generations of women and families have ordered their lives. Make no mistake, the same court that just 24 hours earlier had determined that the decision to carry a gun on the streets is such an essential aspect of personal liberty that states may not be permitted to regulate it has now declared that decisions about abortion, miscarriage, contraception, economic survival, child-rearing, and intimate family matters are worthy of zero solicitude. None. In their view of liberty, women were worthy of zero solicitude at the founding, and remain unworthy of it today. As Mark Joseph Stern notes, women will suffer. Some will be refused treatment for miscarriages, and some will be turned away from emergency rooms. Some will be hunted down, spied on, and prosecuted for seeking health care, medication, and autonomy. The majority glibly tells us that because the harms to these people are unknowable, they are not urgent—or at the very least, less urgent than the harms faced by people who would like to see more guns in public spaces.

But ordinary Americans do not think these harms are trivial. On Thursday, Gallup polling showed public approval for the Supreme Court to be at a historic low—25 percent. It’s a precipitous drop from the prior historic low the court received in September, which sat at about 38 percent. The six justices in the majority of Dobbs will comfort themselves that this doesn’t matter. They will tell themselves that they corrected a historical injustice and that they saved unborn babies. They will say that they have lifetime tenure in order to protect against the whims of the majorities. They will blame protesters and they will continue to blame the press. Even the much-vaunted centrism and pragmatism of Chief Justice John Roberts seems to have left the building. Notwithstanding the fact of his seemingly moderate concurrence—in joining with a majority that could not wait to do in three years what they could do in one—it is clear that he has lost his court, and that he is surely less worried about the public regard for the institution than we had believed.

The joint dissent, authored together by Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor, is elegiac in tone. It includes a shoutout to the three Republican appointees who crossed the partisan line to preserve Roe in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey—not because they liked abortion but because, as they write, they chose to privilege the legitimacy of the institution over their personal wants. Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor wrote of the triumvirate that came before them, and of their unwillingness to harm the standing of the institution they loved:

“[T]he Court,” Casey explained, “could not pretend” that overruling Roe had any “justification beyond a present doctrinal disposition to come out differently from the Court of 1973…. To reverse prior law “upon a ground no firmer than a change in [the Court’s] membership”— would invite the view that “this institution is little different from the two political branches of the Government.” No view, Casey thought, could do “more lasting injury to this Court and to the system of law which it is our abiding mission to serve. For overruling Roe, Casey concluded, the Court would pay a “terrible price.”

The dissent laments the loss of Souter, O’Connor, and Kennedy as “judges of wisdom.” The three write, “They knew that ‘the legitimacy of the Court [is] earned over time.’ ” They also would have recognized that it can be destroyed much more quickly. Quoting Breyer’s recent lament that “it is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much,” the three dissenters conclude: “For all of us, in our time on this Court, that has never been more true than today.”

Compare this to Justice Samuel Alito’s flippant dismissal of the pain soon to be heaped upon the court, the country, women, their children, and families, pain that is laid out in one meticulous amicus brief after the next:

We do not pretend to know how our political system or society will respond to today’s decision overruling Roe and Casey. And even if we could foresee what will happen, we would have no authority to let that knowledge influence our decision. We can only do our job, which is to interpret the law, apply longstanding principles of stare decisis, and decide this case accordingly.

It is one thing to take away autonomy and dignity. It’s something else entirely to say that the hardship and jolt to the nation cannot be determined, and shouldn’t even matter.

The three dissenters take no joy in decrying the self-administered body blow the court has brought upon itself this term. There is no pleasure in seeing new fencing around the building, nor is there any delight in the protesters blocking D.C. streets or staking out justices’ residences. There is no mention of the fact that one of their colleagues is married to a partisan political operator who worked to support those who would have set aside the presidential election. There is simply the acceptance of that colleague’s abject refusal to take responsibility for it. This may well be one of the last published opinions of Stephen Breyer’s storied legal career, and it reads like a rebuke to his own aspirational hopes, including in a book published only this fall, for an institution he tried to protect until the end. Breyer always understood that public acceptance and regard aren’t demanded, and that for the court he is departing, it may not come back.

The dissenters understand where to place the blame for this loss of legitimacy. Even in the notoriously collegial Supreme Court, they place it squarely, and fairly, on a majority that has spent a year proving itself unwilling to moderate tone, language, conduct, and pace in exchange for the appearance of sobriety. The “stench,” as Sotomayor once warned, will not dissipate just because the majority can’t smell it.

The Supreme Court’s Conservatives Are Absolute Weasels

My Boyfriend Recently Introduced Me to His Family. Turns Out I Already, Uh, “Knew” His Brother.

One Story That Shows Amy Coney Barrett’s “Plan” for Abortion Isn’t One at All

There will not be a glorious peace that settles over the land now that this issue has been sent back to the states, no matter how much Justice Brett Kavanaugh wants you to believe it. There will be infighting among states, and vicious criminal prosecutions, and joyous theological efforts to secure future harms for gay partners and families struggling with IVF and women seeking contraception. The people who suffer the most will be the poorest, the youngest, the sickest—the people whose interests don’t even warrant acknowledgment by the majority opinion.

The dissenters sign off in “sorrow.” It is a sentiment that is surely directed at millions of women who will suffer appallingly as a result of this ruling. But it is also sorrow for an institution that was always rooted in an idea that there had to be a relationship between the public trust and judicial power. Justices are not kings. They can demand silent reverence, but it is not assured them. There have been plenty of us warning that this relationship was in jeopardy for many years, and the warnings were dismissed as efforts to undermine the court. Today’s decision confirms that, if and when the public is finally ready to give up on the court, there will be nobody to blame but the six justices who gave them nothing to believe in.

Read more of Slate’s coverage on abortion rights here.

No comments:

Post a Comment