Timothy S Rich, Ian Milden and Annie Whaley

Aug 7 2022 •

Vladimirkarp/Shutterstock

Download PDF

In wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, a number states and trading blocs within the international system have placed sanctions on Russia. These sanctions have affected Russia’s ability to interact with the international financial system, forcing Russia to default on its debt for the first time since 1998. Several countries have also banned Russian exports, including oil and gas. Here, we ask to what extent the American public supports sanctions, especially if it may economically affect themselves, and what polling data tells us about this.

In general, sanctions rarely are effective unless they are well coordinated with broad global support. For example, sanctions on Russian gas have not been effective in reducing demand in many developing countries, who rely on Russian gas supply networks for their energy infrastructure. Sanctions have also harmed U.S. business interests in Russia by blocking payments from Russian banks and forcing businesses to sell assets in Russia at unfavorable prices.

Surveys in the initial months after the Russian invasion show that Americans are supportive of sanctions, but, significantly, does support decline if sanctions lead to reflexive economic costs? A PBS, NPR, and Marist College poll from March 2022 found that 83% of Americans supported economic sanctions on Russia, with 69% willing to accept higher energy prices as a result. Likewise, in the same month a CBS News poll found 63% supported sanctions, even if gas prices increased, alongside a Washington Post and ABC News poll in April which found respondents both supportive of stronger economic sanctions (67%) and concerned about sanctions contributing to rising food and energy prices (66%). A Monmouth University poll in May found that not only did 77% of Americans support sanctions, but 78% supported import bans on Russian oil.

However, on the other hand, most surveys only ask about potential costs after evaluating general support for sanctions, which may artificially inflate cost tolerance. Nor is it clear how important responding to Russia is to the public. A Gallup poll from February 2022 found that most Americans did not place the Russo-Ukrainian conflict at the top of their list of the most important issues. Even post-invasion, sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be viewed as more important than domestic factors, such as inflation or gasoline prices, that would have a more direct impact on their lives.

To address support for sanctions, we conducted an original national web survey in the US from June 29th to July 11th 2022, via Qualtrics, with quota sampling for age, gender, and geographic region. We randomly assigned 1,728 Americans to receive one of three statements to evaluate on a five-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and then explored this in relation to support for the two major US parties (Republicans and Democrats).

The statements were:

In wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, a number states and trading blocs within the international system have placed sanctions on Russia. These sanctions have affected Russia’s ability to interact with the international financial system, forcing Russia to default on its debt for the first time since 1998. Several countries have also banned Russian exports, including oil and gas. Here, we ask to what extent the American public supports sanctions, especially if it may economically affect themselves, and what polling data tells us about this.

In general, sanctions rarely are effective unless they are well coordinated with broad global support. For example, sanctions on Russian gas have not been effective in reducing demand in many developing countries, who rely on Russian gas supply networks for their energy infrastructure. Sanctions have also harmed U.S. business interests in Russia by blocking payments from Russian banks and forcing businesses to sell assets in Russia at unfavorable prices.

Surveys in the initial months after the Russian invasion show that Americans are supportive of sanctions, but, significantly, does support decline if sanctions lead to reflexive economic costs? A PBS, NPR, and Marist College poll from March 2022 found that 83% of Americans supported economic sanctions on Russia, with 69% willing to accept higher energy prices as a result. Likewise, in the same month a CBS News poll found 63% supported sanctions, even if gas prices increased, alongside a Washington Post and ABC News poll in April which found respondents both supportive of stronger economic sanctions (67%) and concerned about sanctions contributing to rising food and energy prices (66%). A Monmouth University poll in May found that not only did 77% of Americans support sanctions, but 78% supported import bans on Russian oil.

However, on the other hand, most surveys only ask about potential costs after evaluating general support for sanctions, which may artificially inflate cost tolerance. Nor is it clear how important responding to Russia is to the public. A Gallup poll from February 2022 found that most Americans did not place the Russo-Ukrainian conflict at the top of their list of the most important issues. Even post-invasion, sanctions on Russia are unlikely to be viewed as more important than domestic factors, such as inflation or gasoline prices, that would have a more direct impact on their lives.

To address support for sanctions, we conducted an original national web survey in the US from June 29th to July 11th 2022, via Qualtrics, with quota sampling for age, gender, and geographic region. We randomly assigned 1,728 Americans to receive one of three statements to evaluate on a five-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and then explored this in relation to support for the two major US parties (Republicans and Democrats).

The statements were:

Version 1: I support sanctions against Russia.

Version 2: I support sanctions against Russia, even if it means US consumers pay more for goods.

Version 3: I support sanctions against Russia, even if it means US consumers pay more for gas.

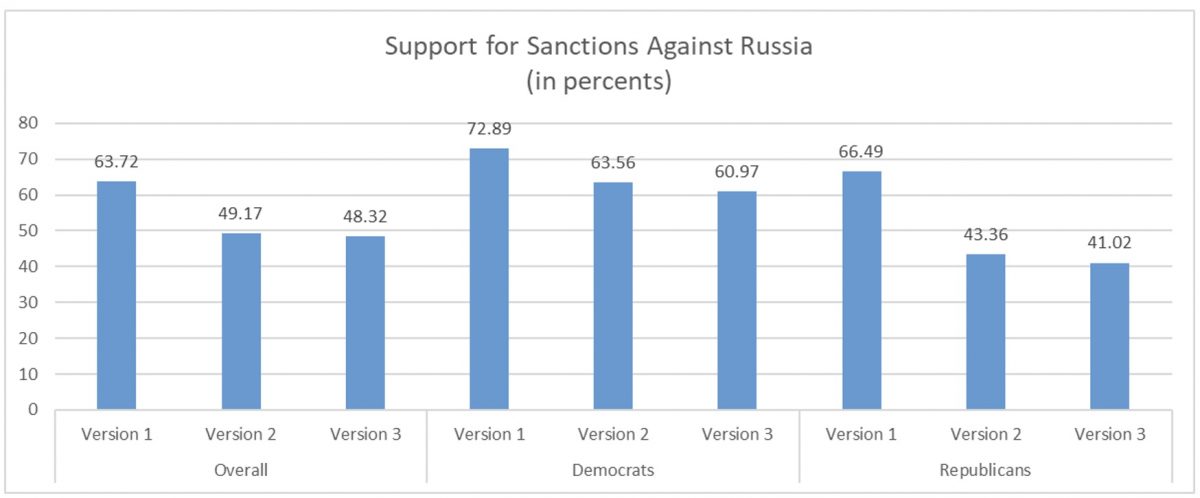

If the public increasingly is risk averse, then costly sanctions, especially ones that would impact already higher prices, would presumably erode sanction support. The figure below shows the percentage of respondents that either agreed or strongly agreed with each statement, broken down by partisan support. Overall, 63.72% of respondents supported sanctions under Version 1, with higher rates among Democrats (72.89%) and Republicans (66.49%). However, when primed to think about potential costs, support declines. Notably, only among Democrats did support remain over 50% in Versions 2 and 3. The results also show limited differences between Versions 2 and 3, suggesting that just the mention of increased costs of any kind depresses support for sanctions.

Additional statistical analysis finds that the only demographic variables corresponding with greater support for sanctions were age and education. That older respondents were more supportive of sanctions may be a function of memories of Cold War hostilities, while education may be picking up greater awareness of Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

When combined with previous survey data on sanctions, our data also suggests that Americans are less willing to tolerate policies targeting foreign actors that increase their cost of living over a sustained period. Americans in the early days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine may not have realized how long the invasion might last for, or even how much prices for goods, such as gasoline, would increase. Nor did previous surveys specify a timeframe for the sanctions or a specific increase in the cost of goods. The data suggests that proponents of sanctions need to either: (a) downplay potential economic and political costs to their constituents, or (b) make a clearer case as to why these are acceptable costs as part of a foreign policy objective to punish Russia, a direction made more difficult as Americans show less interest in engagement in foreign affairs overall.

The public’s diminishing support for economic sanctions against an overseas aggressor perhaps is a sign of a general growing apathy towards American engagement abroad in favor of “America First” isolationist sentiments. A history of economic and military interventions, highlighted by decades-long wars in the Middle East, at the same time as domestic challenges increase, may have forged a public more sensitive to the costs of international engagement. Whether the public would re-engage based on the perceived proximity of the threats is less clear, but a U.S. that pulls back on long-established interventionist policies would have a tangible change in the lives of those overseas and reframe the role of U.S. as a geopolitical power.

This survey work was funded by generous support by the Mahurin Honors College at Western Kentucky University.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

No comments:

Post a Comment