‘I’m not a shaman – I just want to help people’: shoe designer Patrick Cox on his psychedelic toad awakening

Patrick Cox with his dog Titus at his home in Ibiza. T-shirt, from the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. Photograph: Karl Grant/The Guardian

The celebrity shoemaker was a fixture of the 90s London scene, then after the collapse of his business – and his mental health – he found salvation from a very unlikely source ...

HadleyFreeman

The celebrity shoemaker was a fixture of the 90s London scene, then after the collapse of his business – and his mental health – he found salvation from a very unlikely source ...

HadleyFreeman

The Guardian

Sat 10 Sep 2022

Sat 10 Sep 2022

LONG READ

‘This morning in my garden I picked literally kilos of tomatoes. What am I supposed to do with kilos of tomatoes?!” asks Patrick Cox, once one of the most famous shoemakers in the world, as he drives me to his home in Ibiza, which he shares with his beloved pit bull, Titus. “It’s got solar panels and a well. So I’m pretty much completely off grid, which is the dream.”

Once, this would have been Cox’s nightmare. “Getting up at 5am to do the gardening? When I was 30, I’d have been like: ‘What the fuck is wrong with you?!’” he says, and makes one of his bend-forward-at-the-belly big laughs. Back in the 90s and early 2000s, Cox, now 59, was shoemaker to the moneyed – through his high-end Patrick Cox line – and the masses, with his cheaper, mega-selling brand Wannabe, whose chunky loafers became the defining footwear of the era. Spindly stilettos by Manolo Blahnik might have made more appearances on Sex and the City, but at their peak Wannabe loafers sold 1m pairs a year. Cox’s handsome, impish face was frequently photographed at all the A-list parties. He was Elizabeth Hurley’s plus-one on the red carpet, best friends with Elton John and David Furnish. “I was the last one every night to hang up my disco shoes,” he says. He wasn’t nicknamed Party Pat by Janet Jackson for nothing.

‘This morning in my garden I picked literally kilos of tomatoes. What am I supposed to do with kilos of tomatoes?!” asks Patrick Cox, once one of the most famous shoemakers in the world, as he drives me to his home in Ibiza, which he shares with his beloved pit bull, Titus. “It’s got solar panels and a well. So I’m pretty much completely off grid, which is the dream.”

Once, this would have been Cox’s nightmare. “Getting up at 5am to do the gardening? When I was 30, I’d have been like: ‘What the fuck is wrong with you?!’” he says, and makes one of his bend-forward-at-the-belly big laughs. Back in the 90s and early 2000s, Cox, now 59, was shoemaker to the moneyed – through his high-end Patrick Cox line – and the masses, with his cheaper, mega-selling brand Wannabe, whose chunky loafers became the defining footwear of the era. Spindly stilettos by Manolo Blahnik might have made more appearances on Sex and the City, but at their peak Wannabe loafers sold 1m pairs a year. Cox’s handsome, impish face was frequently photographed at all the A-list parties. He was Elizabeth Hurley’s plus-one on the red carpet, best friends with Elton John and David Furnish. “I was the last one every night to hang up my disco shoes,” he says. He wasn’t nicknamed Party Pat by Janet Jackson for nothing.

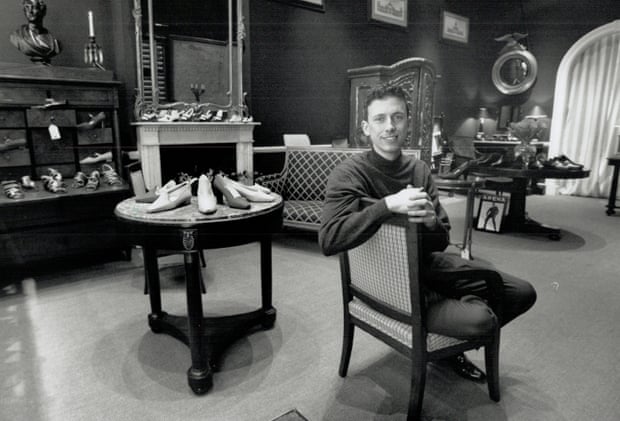

Patrick Cox in his Toronto store in 1992.

At their peak, his Wannabe loafers sold 1m pairs a year.

Photograph: Getty Images

Then suddenly, he seemed to disappear. Out of the blue, he emailed me this summer and wrote that he’s working on a documentary about his new life as a toad facilitator. “A toad what?!” Cox himself would have once replied. A toad facilitator is someone who helps people while they smoke toad poison, also known as 5-MeO‑DMT, the strongest hallucinogen known to man.

“I know, it’s such a cliche: ‘Patrick moves to Ibiza and becomes a shaman.’ But I am not a shaman and never will be. I just want to be part of something that is helping people,” he says.

Helping them to smoke toad poison?

“I am aware of how ridiculous it can seem, but I don’t care.”

Then suddenly, he seemed to disappear. Out of the blue, he emailed me this summer and wrote that he’s working on a documentary about his new life as a toad facilitator. “A toad what?!” Cox himself would have once replied. A toad facilitator is someone who helps people while they smoke toad poison, also known as 5-MeO‑DMT, the strongest hallucinogen known to man.

“I know, it’s such a cliche: ‘Patrick moves to Ibiza and becomes a shaman.’ But I am not a shaman and never will be. I just want to be part of something that is helping people,” he says.

Helping them to smoke toad poison?

“I am aware of how ridiculous it can seem, but I don’t care.”

I always had this voice in my head that I wasn’t good enough. But this isn’t some sob story. I had an amazing time. Until it stopped

It’s my first day in Ibiza and Cox has kindly picked me up from the airport to spare me the taxi queue. When I last saw him, 15 years ago, he was wearing a smart suit. Despite being Canadian, Cox always dressed like the nattiest of Englishmen. Today, he’s wearing a button-down shirt with a magic mushroom print and loose, tie-dyed trousers. “Welcome to the Toad-mobile!” he says as we climb into his bright green Jeep. Instead of his once-signature brogues, he is wearing a pair of multicoloured slip-ons made out of, he says, “old carpets”. Did he change his wardrobe when he changed his career? “Ha! My friends ask that, but I’ve had a lot of these clothes for 20 years. I’m just putting them together in a different way now,” he says with the cackle that punctuates most of his sentences.

Cox lost his eponymous shoe line in 2007 due to various business shenanigans. “We went into kind of, like, this bankruptcy state. It gets very technical,” he explains. Suffice to say, there was overexpansion, a new CEO and an investor who ended up taking over the company. “Then I got hit by a car and spent six weeks in hospital. It was bad, bad, bad,” he says. He’d already lost Wannabe a few years earlier when the Italian factory where the shoes were made “ended up being taken over by the mafia. I didn’t go back to that part of Italy for a few years, let’s just say, ha ha ha!” In his small but very pretty home in Ibiza, there are occasional mementoes from the glory days: photos of old friends such as Kylie Minogue and Natalie Imbruglia; pictures in the bathroom of him with Elton John, Elizabeth Hurley and … the Queen. “That was from some event called something like Canadians of Note, when Canadians who had made a contribution to the country were invited to the Palace. David Furnish and I were like: ‘Who besides us will be there?!’” he says. (A lot of Canadians who work in the foreign service turned out to be the answer.)

Cox at home in Ibiza, where he moved in 2017.

Photograph: Karl Grant/The Guardian

But in the main, his home feels blissfully far from the frenetic London world he once lived in and loved. Cox moved to Ibiza in 2017, and he has resisted the usual decor cliches of the island: instead of wind chimes, he has 18th-century plaster casts of ancient Greek friezes on the walls. “I bought them in the south of France with Elton,” he says. “For the first time, I managed to get something before Elton got them, because shopping with him is insane. You see something you like and he’s already bought six of them.”

Outside, Titus sleeps in the sun. Despite Cox’s previous aversion to gardening, he has a garden that verges on Eden-like behind his house, with orange and lemon trees, and rows of artichokes, courgettes, onions, carrots. It looks like absolute paradise, I tell him. “Well, if you’d come in 2018 you’d have found me lying on the floor where you’re standing now. I was crying, beyond depressed, I couldn’t even stand up. I was completely desperate,” he says, then takes a pause. “Let’s sit down, because this will take a while.” And for the next several days, we sit on his terrace and we talk.

Cox was born in Edmonton, Alberta, and his childhood was complicated. His father worked as a teacher overseas, and by the time Cox was eight he had lived in Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon, with moves back to Canada in between each posting. In 1971, Cox’s mother left his father, and when she landed back in Alberta with her two young sons, she discovered her husband had cut off all their financial support. Cox went from living in relative luxury in the southern hemisphere to being a latchkey kid in a two-room basement in western Canada, and he wouldn’t see his father for another decade. His mother struggled to cope. (He is now on good terms with her and has made efforts to re‑establish a relationship with his father.) He left home as soon as he could at 17 – a gay, disco-loving, fashion-obsessed teenager already looking for the party. He moved to Toronto, and from there to London to study shoe design in 1983.

But in the main, his home feels blissfully far from the frenetic London world he once lived in and loved. Cox moved to Ibiza in 2017, and he has resisted the usual decor cliches of the island: instead of wind chimes, he has 18th-century plaster casts of ancient Greek friezes on the walls. “I bought them in the south of France with Elton,” he says. “For the first time, I managed to get something before Elton got them, because shopping with him is insane. You see something you like and he’s already bought six of them.”

Outside, Titus sleeps in the sun. Despite Cox’s previous aversion to gardening, he has a garden that verges on Eden-like behind his house, with orange and lemon trees, and rows of artichokes, courgettes, onions, carrots. It looks like absolute paradise, I tell him. “Well, if you’d come in 2018 you’d have found me lying on the floor where you’re standing now. I was crying, beyond depressed, I couldn’t even stand up. I was completely desperate,” he says, then takes a pause. “Let’s sit down, because this will take a while.” And for the next several days, we sit on his terrace and we talk.

Cox was born in Edmonton, Alberta, and his childhood was complicated. His father worked as a teacher overseas, and by the time Cox was eight he had lived in Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon, with moves back to Canada in between each posting. In 1971, Cox’s mother left his father, and when she landed back in Alberta with her two young sons, she discovered her husband had cut off all their financial support. Cox went from living in relative luxury in the southern hemisphere to being a latchkey kid in a two-room basement in western Canada, and he wouldn’t see his father for another decade. His mother struggled to cope. (He is now on good terms with her and has made efforts to re‑establish a relationship with his father.) He left home as soon as he could at 17 – a gay, disco-loving, fashion-obsessed teenager already looking for the party. He moved to Toronto, and from there to London to study shoe design in 1983.

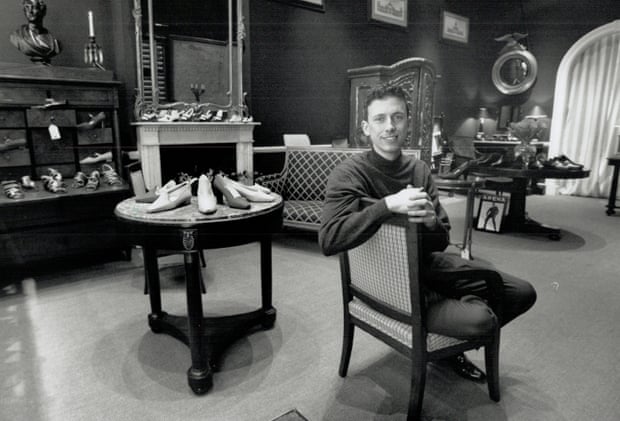

With Boy George in 1987. Photograph: Getty Images

His progress through the British fashion world is like a snapshot of the 1980s London style scene in all its ramshackle glory. He first worked for Vivienne Westwood, after meeting some of her employees in the bathroom of a club. He made moccasins by hand for the influential label BodyMap, and then worked for John Galliano after they bonded at the now-legendary 80s nightclub Taboo over a shared love of Madonna. (“We did the whole Like a Virgin routine, and John was always Madonna and I was always one of the backing boys.”) He launched his own label when he was in his mid-20s, and it did pretty well, selling around 3,000 pairs a season. But when he started Wannabe in the mid-90s, he went stratospheric. Before he had to work in his own stores to keep them going, but now he had to hire doormen to keep the crowds at bay. “I knew Elton because he came to my store and bought more shoes than anyone I’ve ever met in my life. Elizabeth came to my store. And these people are still my best, best friends,” he says.

His progress through the British fashion world is like a snapshot of the 1980s London style scene in all its ramshackle glory. He first worked for Vivienne Westwood, after meeting some of her employees in the bathroom of a club. He made moccasins by hand for the influential label BodyMap, and then worked for John Galliano after they bonded at the now-legendary 80s nightclub Taboo over a shared love of Madonna. (“We did the whole Like a Virgin routine, and John was always Madonna and I was always one of the backing boys.”) He launched his own label when he was in his mid-20s, and it did pretty well, selling around 3,000 pairs a season. But when he started Wannabe in the mid-90s, he went stratospheric. Before he had to work in his own stores to keep them going, but now he had to hire doormen to keep the crowds at bay. “I knew Elton because he came to my store and bought more shoes than anyone I’ve ever met in my life. Elizabeth came to my store. And these people are still my best, best friends,” he says.

If you were even vaguely interested in style in the late 90s and early 00s, Cox seemed ubiquitous: he helped to fund the magazine Wallpaper*, which was created by his then boyfriend Tyler Brûlé; he had stores around the world, adverts in every magazine. He was friends with everyone because he was fun to be around, and he still is: in all our time together, we drink nothing stronger than water, but he never runs out of energy, always full of “OK, now this is really off the record” anecdotes. I can’t even imagine what he was like when he was still, as he puts it, “partying”.

Does he mean “partying” in the euphemistic sense?

“Yeah, yeah, cocaine, drinking – let’s blow that euphemism apart,” he says. But despite his success he was riddled with self-doubt: “I always had this voice in my head that I wasn’t good enough, that I didn’t know what I was doing. Even when I won accessories designer of the year twice [at the British Fashion Awards], I thought: ‘Well, they made a mistake.’”

Did that voice come from his parents?

“Yeah. Telling me that I wasn’t good enough. But look, this isn’t some sob story. I had an amazing time. Until it stopped.”

I felt I had to please everyone, to prove I wasn’t as worthless as I knew I was. Then it all collapsed. Who even was I now?

When Cox lost his labels, he had a breakdown. He became so agoraphobic he couldn’t leave his house in west London, and when his PA eventually dragged him to therapy, he clung desperately to the lamp-post in the road. “Ever since I was four, I felt like I had to please everyone, trying to prove to myself that I wasn’t as worthless as I knew I was. And then it all collapsed. Who even was I now?” he says. He had been single since breaking up with Brûlé in 1997, “because how can you love someone when you can’t love yourself?” He went through the Hoffman Process, an intensive seven days of therapy that participants are not allowed to discuss afterwards, but Cox sums it up as “you prosecute your parents”. They patched him up enough that afterwards he was able to dabble in some ventures: he opened a saucy bakery in London called Cox, Cookies & Cake (“As in cock, balls and fanny,” he explains helpfully), and designed shoes occasionally for other brands. But he had made enough money in fashion to not have to work very much at all, and in 2017 decided he needed another change, so he and his two bulldogs, Brutus and Caesar, moved to Ibiza – where he later got Titus. “It was great at first. But then this cunt called Patrick Cox followed me out here,” he says.

In 2019 with Elizabeth Hurley, who staged an intervention with Elton John and David Furnish when Cox hit his lowest point.

Photograph: Getty Images

He went into a severe depression, triggered when Brutus suddenly died in Ibiza while Cox was back in London for Kylie Minogue’s 50th birthday. “So I had that extra self-flagellation of feeling like: so not only has my dog died, but it happened while I was in London at a pop star’s birthday, doing things I didn’t want to be doing any more. I mean, Kylie is a friend, not just some pop star, but yeah. I completely flipped out,” he says. He talked to friends about wanting to kill himself. “Elizabeth is so no-nonsense, so she was like: ‘Well, you are NOT doing that.’ Then unbeknownst to me, she called David and Elton and said: ‘I think we need to do an intervention.’”

By now, Elton John has a long record of swooping in and packing substance-addicted celebrities off to rehab, sometimes successfully (Eminem, Rufus Wainwright, Donatella Versace), sometimes less so (George Michael replied to Elton’s offer of assistance in an open letter: “Elton John needs to shut up and get on with his life”). Cox didn’t think drugs were his problem, but he was grateful for any help, so Elton sent in the cavalry, which in this case meant his private plane. “He knew I wouldn’t leave Ibiza without Caesar, especially after what had happened to Brutus, so he very kindly sent the plane for us,” he says, and he shows me photos on his phone of a nonplussed bulldog sitting in a private plane. When they landed in England, Elton’s bodyguard drove off with Caesar in a Bentley to stay with the pop star and his family, and Cox was packed off to rehab.

He pauses at this point and walks me around the side of his house. There, under a tree, is Caesar’s gravestone, the bulldog who went on more private planes than I ever will. Next to that is the one for Brutus. Cox is still single, and while he may struggle with accepting love from a partner, he has no such difficulties when it comes to his dogs, and he becomes a little tearful when talking about the ones that are gone. It is possibly no coincidence that it was when Caesar’s health started to fail in the summer of 2019 that Cox discovered what he always calls “toad”.

Rehab stopped Cox from killing himself, but he was too much of a cynic to buy into the 12-step programme. “I kept saying: ‘What is this, a Moonie cult? I understand you’ve saved millions of people’s lives, but you do have a huge failure rate. There must be something more,’” he says.

In the past decade, there has been an enormous amount of research into whether psychedelics can alleviate mental health conditions, especially depression, anxiety and PTSD. Of course for every medical study proving the psychological benefits of LSD, you can find an anecdote about someone losing their mind after a bad acid trip. But the theory that psychedelics can be beneficial has definitely gone mainstream. Cox had always been sceptical about the grand claims people make for psychedelics: “I thought it was people just wanting to be high,” he says. But he tried microdosing LSD and was amazed at the instant impact on his mental state. But, he complained to a friend, it aggravated his stomach. “Maybe you should try some toad,” his friend replied.

Toad – or 5-MeO-DMT – is found in the poison of Bufo alvarius, a toad native to the Sonoran desert in Mexico. To extract it, the toads are “milked”, and the poison is then dried, and when it is smoked in a pipe the heat burns off the poison (so don’t go around licking toads, unless you want to be poisoned). The milking doesn’t hurt the toads, although it does potentially leave them defenceless against predators. But 5-MeO-DMT can also be made synthetically, and while some toad purists balk at that, Cox says the synthetic version is just as good as the natural version, but much stronger. Like all psychedelics, it is non-addictive, but it still comes with massive risks: a handful of people are known to have died from smoking toad, and anyone with heart or kidney conditions, or a predisposition to psychosis or schizophrenia, should stay well away. It is extremely fast acting and very strong – up to six times stronger than the better-known and similarly named hallucinogen DMT, which is why it has become known as the “Mount Everest of psychedelics”, as one bestselling book about psychedelics put it. Fans of toad insist that, despite its reputation, it’s a lot easier to handle than other hallucinogens. Unlike mushrooms and LSD, its effects only last for about 15 minutes, and unlike ayahuasca, there is no vomiting and purging. They claim there is no hangover or comedown afterwards, but rather they feel clear-headed and calm. I heard about one 5-MeO-DMT fan who smokes it an hour before doing the afternoon school run, as if she were grabbing an extra latte.

He went into a severe depression, triggered when Brutus suddenly died in Ibiza while Cox was back in London for Kylie Minogue’s 50th birthday. “So I had that extra self-flagellation of feeling like: so not only has my dog died, but it happened while I was in London at a pop star’s birthday, doing things I didn’t want to be doing any more. I mean, Kylie is a friend, not just some pop star, but yeah. I completely flipped out,” he says. He talked to friends about wanting to kill himself. “Elizabeth is so no-nonsense, so she was like: ‘Well, you are NOT doing that.’ Then unbeknownst to me, she called David and Elton and said: ‘I think we need to do an intervention.’”

By now, Elton John has a long record of swooping in and packing substance-addicted celebrities off to rehab, sometimes successfully (Eminem, Rufus Wainwright, Donatella Versace), sometimes less so (George Michael replied to Elton’s offer of assistance in an open letter: “Elton John needs to shut up and get on with his life”). Cox didn’t think drugs were his problem, but he was grateful for any help, so Elton sent in the cavalry, which in this case meant his private plane. “He knew I wouldn’t leave Ibiza without Caesar, especially after what had happened to Brutus, so he very kindly sent the plane for us,” he says, and he shows me photos on his phone of a nonplussed bulldog sitting in a private plane. When they landed in England, Elton’s bodyguard drove off with Caesar in a Bentley to stay with the pop star and his family, and Cox was packed off to rehab.

He pauses at this point and walks me around the side of his house. There, under a tree, is Caesar’s gravestone, the bulldog who went on more private planes than I ever will. Next to that is the one for Brutus. Cox is still single, and while he may struggle with accepting love from a partner, he has no such difficulties when it comes to his dogs, and he becomes a little tearful when talking about the ones that are gone. It is possibly no coincidence that it was when Caesar’s health started to fail in the summer of 2019 that Cox discovered what he always calls “toad”.

Rehab stopped Cox from killing himself, but he was too much of a cynic to buy into the 12-step programme. “I kept saying: ‘What is this, a Moonie cult? I understand you’ve saved millions of people’s lives, but you do have a huge failure rate. There must be something more,’” he says.

In the past decade, there has been an enormous amount of research into whether psychedelics can alleviate mental health conditions, especially depression, anxiety and PTSD. Of course for every medical study proving the psychological benefits of LSD, you can find an anecdote about someone losing their mind after a bad acid trip. But the theory that psychedelics can be beneficial has definitely gone mainstream. Cox had always been sceptical about the grand claims people make for psychedelics: “I thought it was people just wanting to be high,” he says. But he tried microdosing LSD and was amazed at the instant impact on his mental state. But, he complained to a friend, it aggravated his stomach. “Maybe you should try some toad,” his friend replied.

Toad – or 5-MeO-DMT – is found in the poison of Bufo alvarius, a toad native to the Sonoran desert in Mexico. To extract it, the toads are “milked”, and the poison is then dried, and when it is smoked in a pipe the heat burns off the poison (so don’t go around licking toads, unless you want to be poisoned). The milking doesn’t hurt the toads, although it does potentially leave them defenceless against predators. But 5-MeO-DMT can also be made synthetically, and while some toad purists balk at that, Cox says the synthetic version is just as good as the natural version, but much stronger. Like all psychedelics, it is non-addictive, but it still comes with massive risks: a handful of people are known to have died from smoking toad, and anyone with heart or kidney conditions, or a predisposition to psychosis or schizophrenia, should stay well away. It is extremely fast acting and very strong – up to six times stronger than the better-known and similarly named hallucinogen DMT, which is why it has become known as the “Mount Everest of psychedelics”, as one bestselling book about psychedelics put it. Fans of toad insist that, despite its reputation, it’s a lot easier to handle than other hallucinogens. Unlike mushrooms and LSD, its effects only last for about 15 minutes, and unlike ayahuasca, there is no vomiting and purging. They claim there is no hangover or comedown afterwards, but rather they feel clear-headed and calm. I heard about one 5-MeO-DMT fan who smokes it an hour before doing the afternoon school run, as if she were grabbing an extra latte.

Some of his friends are sceptical: ‘They’re like: You call it doing the work and holding space, Patrick. But it’s called taking drugs’

There is no evidence that smoking toad poison was part of any ancient indigenous tradition. Instead, it is a late 20th-century discovery, and one that is now rocketing in popularity: Mike Tyson, of all people, said smoking toad has helped him to be “more creative”. It is illegal to possess and distribute 5-MeO‑DMT in the US and UK, and it is illegal to supply it in Spain, and in recent years several people have been arrested there for hosting toad ceremonies; in 2020, several people, including the porn actor Nacho Vidal, were arrested after a photographer died at a toad ceremony in Valencia. Vidal was later charged for reckless homicide – he maintains his innocence. But there are a growing number of “toad retreats”, on which the wealthy pay thousands of pounds to go to Central or South America – where toad is legal – to smoke it. It is likely that toad will go the same way ayahuasca has over the past decade – not mainstream exactly, but commodified and something a certain type of person likes to tick off their bucket list, along with bungee jumping in Australia and off-piste skiing in Japan. It is, allegedly, already popular among Silicon Valley titans.

In his 2018 book How To Change Your Mind: the New Science of Psychedelics, the award-winning writer Michael Pollan says his experience of smoking toad was “just horrible”, but it also gave him “a sense of relief so vast and deep as to be cosmic”. Unlike with DMT, acid and mushrooms, you don’t have visions. “It’s an experiential drug. You don’t see things when you take it. You experience them,” says Cox. And he experienced them so deeply that when he came round after taking it he found that, for the first time in his life, “I didn’t hate myself any more. There was nothing wrong with me. I’d never known that before. And now I did.” Studies have shown that 5-MeO-DMT has a psychotherapeutic effect, with some people feeling “greater life satisfaction” after trying it.

There is no evidence that smoking toad poison was part of any ancient indigenous tradition. Instead, it is a late 20th-century discovery, and one that is now rocketing in popularity: Mike Tyson, of all people, said smoking toad has helped him to be “more creative”. It is illegal to possess and distribute 5-MeO‑DMT in the US and UK, and it is illegal to supply it in Spain, and in recent years several people have been arrested there for hosting toad ceremonies; in 2020, several people, including the porn actor Nacho Vidal, were arrested after a photographer died at a toad ceremony in Valencia. Vidal was later charged for reckless homicide – he maintains his innocence. But there are a growing number of “toad retreats”, on which the wealthy pay thousands of pounds to go to Central or South America – where toad is legal – to smoke it. It is likely that toad will go the same way ayahuasca has over the past decade – not mainstream exactly, but commodified and something a certain type of person likes to tick off their bucket list, along with bungee jumping in Australia and off-piste skiing in Japan. It is, allegedly, already popular among Silicon Valley titans.

In his 2018 book How To Change Your Mind: the New Science of Psychedelics, the award-winning writer Michael Pollan says his experience of smoking toad was “just horrible”, but it also gave him “a sense of relief so vast and deep as to be cosmic”. Unlike with DMT, acid and mushrooms, you don’t have visions. “It’s an experiential drug. You don’t see things when you take it. You experience them,” says Cox. And he experienced them so deeply that when he came round after taking it he found that, for the first time in his life, “I didn’t hate myself any more. There was nothing wrong with me. I’d never known that before. And now I did.” Studies have shown that 5-MeO-DMT has a psychotherapeutic effect, with some people feeling “greater life satisfaction” after trying it.

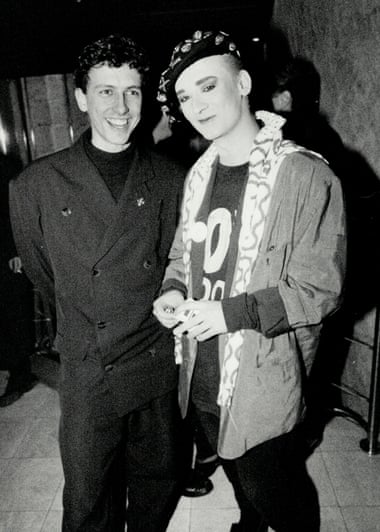

Cox with his friends Elton John and David Furnish in 2015.

Photograph: Getty Images

Advertisement

Cox smokes toad on average once a month “the way some people might go to church or mosque or synagogue”, he says. Because toad is not about getting high, but healing and “doing the work” – exploring what toad shows him. I assumed that being a “toad facilitator” was someone who sells toad poison – a drug dealer, in other words – but it turns out to be more like a drug doula: he “holds the space”for people who smoke it, a psychedelic term for sitting with someone who is smoking and making sure they feel safe. “Watching someone go through these huge transformations – there’s nothing better than that,” says Cox with feeling. He himself has gone through a huge transformation. His devotion to toad was so quick and full-hearted that he was chosen by Cesar Reyes, a very experienced toad facilitator, to be his apprentice (Reyes, 49, died last December from cancer; memories of him spark even more tears from Cox than references to Brutus and Caesar). He no longer drinks alcohol or does any drugs (other than toad) because, he says, they sever the feeling of connection he gets from toad. When he visited Elton John and Furnish in 2019, they told him they hadn’t seen him so happy in years, and he told them he had started smoking toad.

Advertisement

Cox smokes toad on average once a month “the way some people might go to church or mosque or synagogue”, he says. Because toad is not about getting high, but healing and “doing the work” – exploring what toad shows him. I assumed that being a “toad facilitator” was someone who sells toad poison – a drug dealer, in other words – but it turns out to be more like a drug doula: he “holds the space”for people who smoke it, a psychedelic term for sitting with someone who is smoking and making sure they feel safe. “Watching someone go through these huge transformations – there’s nothing better than that,” says Cox with feeling. He himself has gone through a huge transformation. His devotion to toad was so quick and full-hearted that he was chosen by Cesar Reyes, a very experienced toad facilitator, to be his apprentice (Reyes, 49, died last December from cancer; memories of him spark even more tears from Cox than references to Brutus and Caesar). He no longer drinks alcohol or does any drugs (other than toad) because, he says, they sever the feeling of connection he gets from toad. When he visited Elton John and Furnish in 2019, they told him they hadn’t seen him so happy in years, and he told them he had started smoking toad.

No one was a bigger cynic than me about psychedelics. Sometimes I hear what comes out of my mouth now and I’m like: Oh my God, shut up!

“Well, I’m really glad we paid for you to go to rehab, Patrick, because it sounds like you’re doing a shitload of drugs,” the singer said drily.

“But then he said: ‘If you’re happy, who am I to judge’, which I thought was just beautiful,” Cox says.

Some of his other friends are a little more sceptical: “They’re like: ‘You call it “doing the work” and “holding space”, Patrick. But it’s called taking drugs,’” he laughs, conceding the point a little.

Before I flew to Ibiza, my editor expressly warned me not to go gonzo and smoke 5-MeO-DMT. But, I tell Cox, even after hours of talking to him, I still have so many questions about toad. Like, doesn’t he think he’s simply substituted a more powerful drug for less satisfying ones? When he says that the world would be better off if everyone smoked toad, is it possible that he has given himself brain damage from all these psychedelics? Cox is spending this autumn filming his documentary, even going to Mexico to see the toads. His commitment to spreading the word is impressive, but is he ready to give up his reputation as a talented shoe designer to be known as the crazy toad guy? “No one was a bigger cynic than me about psychedelics, and sometimes I hear the stuff that comes out of my mouth now and I’m like: ‘Oh my God, shut up!’ But trying to explain toad to someone who has never taken it is like trying to explain sex to someone who has only ever watched it,” he says. Pretty convenient fob-off, the sceptical side of my brain says. The curious part says: “Well, let’s smoke some toad, then.”

Wearing his toad T-shirt with Titus.

Photograph: Karl Grant/The Guardian

Firmly ignoring my editor’s instruction, I find someone, who I’ll call C, who has toad, and I ask Cox to come with me to see him and keep me safe – to hold the space. He replies firmly that I’ll first have to answer some questions. After ascertaining whether I have any history of cardiac problems, depression or psychosis (none all round), he asks if I’ve had any alcohol or narcotics in the past three days, whether I’m on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, a common kind of antidepressant, which combined with toad can lead to the potentially fatal serotonin syndrome), and if I’m just doing this to get high. I answer in the negative to all, so he agrees. I hand over €200 of my own money to C and he tells me to sit on a mat on the ground and to breathe through my mouth. He weighs a small amount of toad poison on a scale and puts it in the bulb of a glass pipe. Cox sits beside me and murmurs a blessing, touching each of my shoulders and my back, while C heats the bulb. As the poison smokes in the bulb, C tells me to take a deep inhale on the glass pipe. I think: “Am I really putting my life and my mind in the hands of Patrick Cox?” And then I don’t think anything at all.

I expected to see fractals, wavy lines, kaleidoscopic colours – the things you might see on an LSD or mushroom trip. Instead, I fall into a darkness that goes beyond blackness, and my mind dissolves. This is what toad fans describe as “ego death”. Somewhere, a bell rings, and I fall deeper and fly higher, and then I experience something that I – normally hyper verbal to a fault – cannot describe.

After an unknowable amount of time (14 minutes, it turns out) the blue sky appears in the darkness, fragment by fragment. Cox is holding my hand, telling me that I am safe. I feel terrified and ecstatic. I look at Cox, and as tears stream down my face, I hear myself say to him, in a voice that doesn’t sound like mine: “Now I understand.”

It’s my last day with Cox and we are back on his terrace. He’s as chipper as ever and I feel, well, great: clear-headed, calm and full of energy. Is this the toad or just the effect of a trip to Ibiza? Cox says all psychedelic experiences are affected by “the set and the setting”, ie your mindset and where you’re doing it. Certainly something has had a strong impact on me, because it no longer seems entirely ridiculous that I smoked toad poison with the man who used to make my loafers.

Cox knows he has the zeal of a convert, and he tries to dial it down a little. When he first got into toad, he grew his hair long, diving into the psychedelic look. Then a friend stood him in front of a mirror and said: “Would you fuck you?” “Point taken!” he hoots at the memory. (Whatever toad has done to him, it has not – thankfully – taken away his sense of humour.) His focus now is to teach people how to do toad safely, and to try to keep it accessible to anyone who wants it, not just the 1% crowd. I ask if he’ll ever go back to fashion and he recoils; instead, he’s thinking of opening an animal sanctuary. A part of him would like to be part of “the psychedelic community”, he says, but the same cynical mindset that resisted rehab pulls him away from joining this group, too: “There’s a lot in that world that I don’t agree with. I’m not a new ageist and I’m not a conspiracy theorist,” he says. Easier just to explore things on his own without putting a label on it, he says.

Firmly ignoring my editor’s instruction, I find someone, who I’ll call C, who has toad, and I ask Cox to come with me to see him and keep me safe – to hold the space. He replies firmly that I’ll first have to answer some questions. After ascertaining whether I have any history of cardiac problems, depression or psychosis (none all round), he asks if I’ve had any alcohol or narcotics in the past three days, whether I’m on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, a common kind of antidepressant, which combined with toad can lead to the potentially fatal serotonin syndrome), and if I’m just doing this to get high. I answer in the negative to all, so he agrees. I hand over €200 of my own money to C and he tells me to sit on a mat on the ground and to breathe through my mouth. He weighs a small amount of toad poison on a scale and puts it in the bulb of a glass pipe. Cox sits beside me and murmurs a blessing, touching each of my shoulders and my back, while C heats the bulb. As the poison smokes in the bulb, C tells me to take a deep inhale on the glass pipe. I think: “Am I really putting my life and my mind in the hands of Patrick Cox?” And then I don’t think anything at all.

I expected to see fractals, wavy lines, kaleidoscopic colours – the things you might see on an LSD or mushroom trip. Instead, I fall into a darkness that goes beyond blackness, and my mind dissolves. This is what toad fans describe as “ego death”. Somewhere, a bell rings, and I fall deeper and fly higher, and then I experience something that I – normally hyper verbal to a fault – cannot describe.

After an unknowable amount of time (14 minutes, it turns out) the blue sky appears in the darkness, fragment by fragment. Cox is holding my hand, telling me that I am safe. I feel terrified and ecstatic. I look at Cox, and as tears stream down my face, I hear myself say to him, in a voice that doesn’t sound like mine: “Now I understand.”

It’s my last day with Cox and we are back on his terrace. He’s as chipper as ever and I feel, well, great: clear-headed, calm and full of energy. Is this the toad or just the effect of a trip to Ibiza? Cox says all psychedelic experiences are affected by “the set and the setting”, ie your mindset and where you’re doing it. Certainly something has had a strong impact on me, because it no longer seems entirely ridiculous that I smoked toad poison with the man who used to make my loafers.

Cox knows he has the zeal of a convert, and he tries to dial it down a little. When he first got into toad, he grew his hair long, diving into the psychedelic look. Then a friend stood him in front of a mirror and said: “Would you fuck you?” “Point taken!” he hoots at the memory. (Whatever toad has done to him, it has not – thankfully – taken away his sense of humour.) His focus now is to teach people how to do toad safely, and to try to keep it accessible to anyone who wants it, not just the 1% crowd. I ask if he’ll ever go back to fashion and he recoils; instead, he’s thinking of opening an animal sanctuary. A part of him would like to be part of “the psychedelic community”, he says, but the same cynical mindset that resisted rehab pulls him away from joining this group, too: “There’s a lot in that world that I don’t agree with. I’m not a new ageist and I’m not a conspiracy theorist,” he says. Easier just to explore things on his own without putting a label on it, he says.

People think change is only possible when you’re younger, and who you are when you’re 30 is who you are for ever, which is crazy

When I told a friend in the fashion world about my interview with Cox, they asked if I thought he had lost his mind. I don’t. I think he’s happy to have found a purpose – to feel needed – after being adrift for so long, and I think he’s relieved to feel as if there’s something greater out there when he’d grown so jaded with the little world he knew. I also think there is something beyond explanation about toad. For the week after I smoked it, I felt calmer and slept better than I had in years. The thought of smoking it every month, as Cox does, blows my mind almost as much as the toad did. But doing it once a year, a kind of psychedelic MOT? That doesn’t sound totally crazy to me any more. It’s entirely possible that Cox is at the forefront of a new understanding of psychology and neurology. It’s also possible that he’s another guy who went to Ibiza and dropped out, and those two things aren’t mutually exclusive.

Cox doesn’t plan to smoke toad for ever, because the goal is to be able to access the feelings without the drug. “People think change is only possible when you’re younger, and who you are when you’re 30, that’s who you are for ever, which is crazy,” he says. When he was 30, he was a famous shoe designer. Now he’s almost 60 and he’s a toad facilitator. I don’t know if we would all benefit from smoking toad poison, as he says, but I do think people would be happier if they had the freedom – and the courage – to keep evolving, as he has done. To not cling on to one identity, but to keep exploring, and to not care if we look, maybe, a bit ridiculous.

It’s my last day and Cox is wearing trousers with an image of Jesus on them and a T-shirt with a giant picture of a toad on it. It matches the charm on his necklace. I hug him goodbye and ask one last question: doesn’t he worry, just a little, about losing his mind on toad?

“Of course not, because I’ll be happy,” he grins, and the golden toad around his neck glints in the sun.

Patrick Cox’s documentary, The Road to Toad, is due to be released in spring 2023.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

No comments:

Post a Comment