The idea sounds so far-fetched it could be the plotline of a doomsday movie or computer game – to blast a tiny craft on an 11-month voyage through space with the aim of crashing it headlong into a big rock seven million miles away, knocking it off its original direction of travel.

By Ilona Amos

An artist's impression of Nasa's Dart ( double asteroid redirection test) craft. Picture: Nasa

But that’s exactly what has just been successfully achieved in a historic ‘planetary defence’ mission led by US space agency Nasa.

Science fiction has become science fact.

Science fiction has become science fact.

The Dart (double asteroid redirection test) project has been years in the planning, conceived to discover whether humans could change the path of a celestial body that was heading on a collision course towards earth.

The 535ft-wide asteroid Dimorphos – a small moon of the larger, 2,560ft-wide asteroid Didymos – was not a danger to the earth.

It was chosen as a target because its short orbit time would allow experts to quickly assess whether a direct hit by the craft had altered its course.

Live footage was broadcast from Dart, a craft the size of a vending machine, showing its final approach towards the asteroid and the moment of impact – in the early hours of 27 September UK time.

Travelling at 14,000mph, the unmanned spacecraft was destroyed when it slammed into the surface of Dimorphos.

The 535ft-wide asteroid Dimorphos – a small moon of the larger, 2,560ft-wide asteroid Didymos – was not a danger to the earth.

It was chosen as a target because its short orbit time would allow experts to quickly assess whether a direct hit by the craft had altered its course.

Live footage was broadcast from Dart, a craft the size of a vending machine, showing its final approach towards the asteroid and the moment of impact – in the early hours of 27 September UK time.

Travelling at 14,000mph, the unmanned spacecraft was destroyed when it slammed into the surface of Dimorphos.

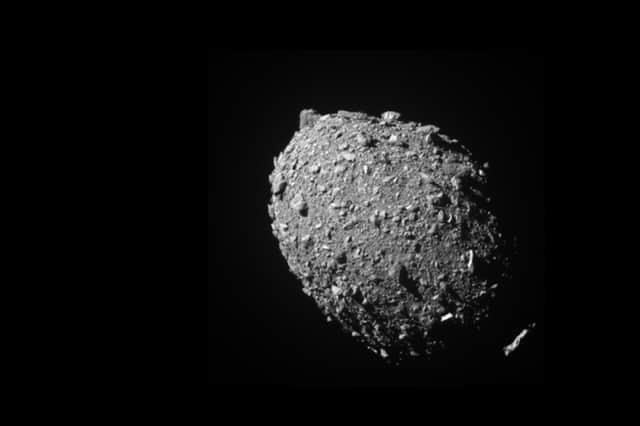

The moonlet Dimorphos, as seen by the Dart spacecraft 11 seconds before impact. While this asteroid posed no threat to Earth, the aim of the mission was to demonstrate that dangerous incoming rocks can be deflected by deliberately smashing into them. Picture: Nasa/Johns Hopkins APL

This week Nasa announced the experiment had been a success, confirming that the hit had altered Dimorphos’s orbit around Didymos by 32 minutes, shortening it from 11 hours and 55 minutes to 11 hours and 23 minutes.

At a briefing at the organisation’s Washington headquarters, Nasa administrator Bill Nelson described it as “a watershed moment for planetary defence and all of humanity”.

He said: “All of us have a responsibility to protect our home planet. After all, it’s the only one we have.

“This mission shows that Nasa is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us.”

This week Nasa announced the experiment had been a success, confirming that the hit had altered Dimorphos’s orbit around Didymos by 32 minutes, shortening it from 11 hours and 55 minutes to 11 hours and 23 minutes.

At a briefing at the organisation’s Washington headquarters, Nasa administrator Bill Nelson described it as “a watershed moment for planetary defence and all of humanity”.

He said: “All of us have a responsibility to protect our home planet. After all, it’s the only one we have.

“This mission shows that Nasa is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us.”

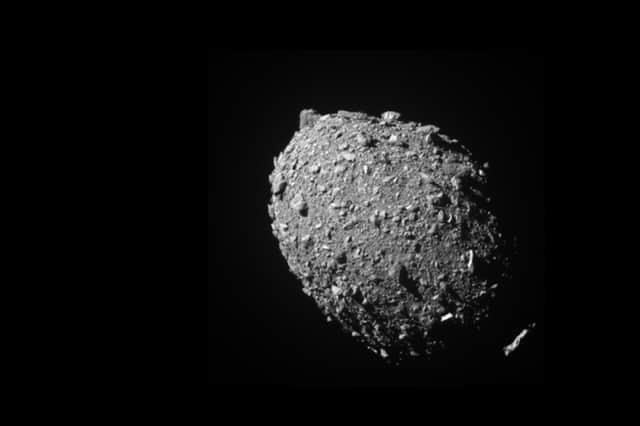

The last complete image of asteroid Dimorphos, taken from seven miles off the surface -- two seconds before the Dart spacecraft crashed into the moonlet. Picture: Nasa/Johns Hopkins APL

Lori Glaze, director of the agency’s Planetary Science Division, added: “This result is one important step toward understanding the full effect of Dart’s impact with its target asteroid.

“As new data come in each day, astronomers will be able to better assess whether, and how, a mission like Dart could be used in the future to help protect earth from a collision with an asteroid if we ever discover one headed our way.”

The investigation team is still gathering information from observatories and other facilities around the globe and updating results to improve precision.

Professor Colin Snodgrass, an astronomer and planetary scientist at the University of Edinburgh’s school of Physics and Astronomy, is part of the international team working on the world-first project and helping to gather information.

The goal of the Dart mission, which launched in November 2021, was to hit an asteroid with a spacecraft to slightly alter its trajectory. Picture: Jim Warson/AFP via Getty Images

He heads up a squad of scientists who have been manning telescopes in strategic locations, watching the mission unfold and documenting the aftermath.

He was back in Scotland on “impact night” but in constant contact with colleagues on the ground in Chile and Kenya and watching Nasa’s live feed.

But despite being alone in his home office in Edinburgh, he found it an unforgettable experience.

“It was all very exciting,” he said.

“It was great.”

The observers in Kenya could see the actual moment of impact through the telescope.

“They could see it was getting brighter in front of their eyes.

“It got bright pretty much instantly, which was a bit of a surprise.

“Most of us expected it would maybe take longer.

“We thought we would see some difference, some brightness change, but we wouldn’t see the sudden cloud of dust coming off the thing.

“They could see the cloud of dust forming live as they were watching – this initial cloud, which is the high-speed ejecta which had been thrown off in the impact.

“Then after that, they have been watching as the long tail of larger particles – the slower ejecta, formed over days and weeks – has been growing.

“At the moment of impact you see this sudden puff as it throws off high-speed stuff and you then get the longer process of growing this tail, which is now thousands of miles long and we can still see with the telescopes.”

Professor Snodgrass stressed the significance of the experiment.

“It’s a test of the technology,” he said.

He heads up a squad of scientists who have been manning telescopes in strategic locations, watching the mission unfold and documenting the aftermath.

He was back in Scotland on “impact night” but in constant contact with colleagues on the ground in Chile and Kenya and watching Nasa’s live feed.

But despite being alone in his home office in Edinburgh, he found it an unforgettable experience.

“It was all very exciting,” he said.

“It was great.”

The observers in Kenya could see the actual moment of impact through the telescope.

“They could see it was getting brighter in front of their eyes.

“It got bright pretty much instantly, which was a bit of a surprise.

“Most of us expected it would maybe take longer.

“We thought we would see some difference, some brightness change, but we wouldn’t see the sudden cloud of dust coming off the thing.

“They could see the cloud of dust forming live as they were watching – this initial cloud, which is the high-speed ejecta which had been thrown off in the impact.

“Then after that, they have been watching as the long tail of larger particles – the slower ejecta, formed over days and weeks – has been growing.

“At the moment of impact you see this sudden puff as it throws off high-speed stuff and you then get the longer process of growing this tail, which is now thousands of miles long and we can still see with the telescopes.”

Professor Snodgrass stressed the significance of the experiment.

“It’s a test of the technology,” he said.

“If we saw one of these things coming towards us, could we nudge it out of the way?

“And the test shows us, yes, we can, we can change its orbit if we need to.”

He was also quick to offer reassurance that the planet was not at imminent risk of being hit by a giant asteroid that could wipe out all life.

“All the really big asteroids, the mass extinction ones, we know where all of those are,” he said.

“Those are all big enough that we’ve been able to see them with telescopes for years.”

But he did admit there is “slight concern” over much smaller asteroids, because a strike could do a lot of damage – and scientists haven’t found them all yet.

“They’re the ones we think a bit more about,” Prof Snodgrass said.

“Didymos, this is the sort of scale where you wouldn’t want it falling on your city.

“It would have the equivalent energy of a nuclear bomb, so it would cause local, regional devastation.

“It’s not the sort of size that would cause mass extinction, kill off all the dinosaurs sort of thing – that one was a few miles across.

“We’re constantly searching, scanning the skies, and we’re finding more of these small ones all the time.

“But we’ve not yet found one that’s coming anywhere near us.

“Eventually, though, we will find one that’s heading in our direction and it’s likely to be of this kind of size, which is why this experiment is useful – it’s testing out the technology to move an asteroid of the sort of size that is realistically likely to arrive at some point.”

Experts expect we would have a bit of advance warning ahead of any potential strike, possibly decades, allowing time to take defensive action.

“It’s not likely that you spot one and go, right, it's coming next week,” he said.

“But if we do spot one that will be here next week, there’s probably not so much we can do about it.

“You would just have to move everybody out of that place and hope there was nothing there that you wanted to keep.”

As part of the Dart mission, the Edinburgh team took over all four telescopes at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, based in the Atacama desert of northern Chile.

They also set up a new observatory in Kenya, which will have a lasting legacy in the country.

The Scottish academics have been helping train a new generation of planetary scientists there and handed over the keys to the new observatory when they departed this week.

Prof Snodgrass said the Dart project has other benefits alongside protecting the earth.

“There’s a huge amount of science that comes out of it,” he said.

“The reason we are working on this and trying to study asteroids and comets is because we’re interested in them scientifically.

“The history of the solar system, how the planets formed, all that kind of thing – you get a lot of clues to that kind of stuff by studying asteroids, these little leftover bits from when the planets were made.

“And this experiment has told us an awful lot about the sort of physical properties of the asteroid, the internal structure, all these things you couldn’t do without this big experiment of blasting a hole in the side.

“So it’s scientifically very valuable as well as having the ‘planetary defence just in case we ever need it’ approach.

“The project has dual uses.

“And all this cool stuff about having a telescope in Kenya also has a dual use.

“The telescope is staying out there and we’re doing all this work with the local university, we’re training up astronomers in the country, which didn’t have many astronomers.

“Some Kenyan students are still out there now, operating the telescope after the Edinburgh team comes home.

“We’ve taught them how to use it, we’ve left them the keys and off they go.

“They’re really great, an enthusiastic bunch. It’s really nice to see that.

“It has been a nice positive extra coming out of the Dart project.”

The professor also admits he’s a secret fan of sci-fi movies such as Armageddon and Deep Impact, which both have plots echoing the dart mission’s objective.

“I love them, particularly the really terrible ones,” he said.

“You just have to disconnect your brain a little bit.

“You know it’s all nonsense but it’s good fun – it’s entertaining nonsense.”

“It’s not likely that you spot one and go, right, it's coming next week,” he said.

“But if we do spot one that will be here next week, there’s probably not so much we can do about it.

“You would just have to move everybody out of that place and hope there was nothing there that you wanted to keep.”

As part of the Dart mission, the Edinburgh team took over all four telescopes at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, based in the Atacama desert of northern Chile.

They also set up a new observatory in Kenya, which will have a lasting legacy in the country.

The Scottish academics have been helping train a new generation of planetary scientists there and handed over the keys to the new observatory when they departed this week.

Prof Snodgrass said the Dart project has other benefits alongside protecting the earth.

“There’s a huge amount of science that comes out of it,” he said.

“The reason we are working on this and trying to study asteroids and comets is because we’re interested in them scientifically.

“The history of the solar system, how the planets formed, all that kind of thing – you get a lot of clues to that kind of stuff by studying asteroids, these little leftover bits from when the planets were made.

“And this experiment has told us an awful lot about the sort of physical properties of the asteroid, the internal structure, all these things you couldn’t do without this big experiment of blasting a hole in the side.

“So it’s scientifically very valuable as well as having the ‘planetary defence just in case we ever need it’ approach.

“The project has dual uses.

“And all this cool stuff about having a telescope in Kenya also has a dual use.

“The telescope is staying out there and we’re doing all this work with the local university, we’re training up astronomers in the country, which didn’t have many astronomers.

“Some Kenyan students are still out there now, operating the telescope after the Edinburgh team comes home.

“We’ve taught them how to use it, we’ve left them the keys and off they go.

“They’re really great, an enthusiastic bunch. It’s really nice to see that.

“It has been a nice positive extra coming out of the Dart project.”

The professor also admits he’s a secret fan of sci-fi movies such as Armageddon and Deep Impact, which both have plots echoing the dart mission’s objective.

“I love them, particularly the really terrible ones,” he said.

“You just have to disconnect your brain a little bit.

“You know it’s all nonsense but it’s good fun – it’s entertaining nonsense.”

No comments:

Post a Comment