By DEE-ANN DURBIN

1 of 20

A customer looks at refrigerated items at a Grocery Outlet store in Pleasanton, Calif.,. on Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022. "Best before” labels are coming under scrutiny as concerns about food waste grow around the world. Manufacturers have used the labels for decades to estimate peak freshness. But “best before” labels have nothing to do with safety, and some worry they encourage consumers to throw away food that’s perfectly fine to eat. (AP Photo/Terry Chea)

As awareness grows around the world about the problem of food waste, one culprit in particular is drawing scrutiny: “best before” labels.

Manufacturers have used the labels for decades to estimate peak freshness. Unlike “use by” labels, which are found on perishable foods like meat and dairy, “best before” labels have nothing to do with safety and may encourage consumers to throw away food that’s perfectly fine to eat.

“They read these dates and then they assume that it’s bad, they can’t eat it and they toss it, when these dates don’t actually mean that they’re not edible or they’re not still nutritious or tasty,” said Patty Apple, a manager at Food Shift, an Alameda, California, nonprofit that collects and uses expired or imperfect foods.

To tackle the problem, major U.K. chains like Waitrose, Sainsbury’s and Marks & Spencer recently removed “best before” labels from prepackaged fruit and vegetables. The European Union is expected to announce a revamp to its labeling laws by the end of this year; it’s considering abolishing “best before” labels altogether.

In the U.S., there’s no similar push to scrap “best before” labels. But there is growing momentum to standardize the language on date labels to help educate buyers about food waste, including a push from big grocers and food companies and bipartisan legislation in Congress.

“I do think that the level of support for this has grown tremendously,” said Dana Gunders, executive director of ReFED, a New York-based nonprofit that studies food waste.

The United Nations estimates that 17% of global food production is wasted each year; most of that comes from households. In the U.S., as much as 35% of food available goes uneaten, ReFED says. That adds up to a lot of wasted energy — including the water, land and labor that goes into the food production — and higher greenhouse gas emissions when unwanted food goes into landfills.

There are many reasons food gets wasted, from large portion sizes to customers’ rejection of imperfect produce. But ReFED estimates that 7% of U.S. food waste — or 4 million tons annually — is due to consumer confusion over “best before” labels.

Date labels were widely adopted by manufacturers in the 1970s to answer consumers’ concerns about product freshness. There are no federal rules governing them, and manufacturers are allowed to determine when they believe their products will taste best. Only infant formula is required to have a “use by” date in the U.S.

Since 2019, the Food and Drug Administration — which regulates around 80% of U.S. food — has recommended that manufacturers use the labels “best if used by” for freshness and “use by” for perishable goods, based on surveys showing that consumers understand those phrases.

But the effort is voluntary, and the language on labels continues to vary widely, from “sell by” to “enjoy by” to “freshest before.” A survey released in June by researchers at the University of Maryland found at least 50 different date labels used on U.S. grocery shelves and widespread confusion among customers.

“Most people believe that if it says ‘sell by,’ ‘best by’ or ‘expiration,’ you can’t eat any of them. That’s not actually accurate,” said Richard Lipsit, who owns a Grocery Outlet store in Pleasanton, California, that specializes in discounted food.

Lipsit said milk can be safely consumed up to a week after its “use by” date. Gunders said canned goods and many other packaged foods can be safely eaten for years after their “best before” date. The FDA suggests consumers look for changes in color, consistency or texture to determine if foods are all right to eat.

“Our bodies are very well equipped to recognize the signs of decay, when food is past its edible point,” Gunders said. “We’ve lost trust in those senses and we’ve replaced it with trust in these dates.”

Some U.K. grocery chains are actively encouraging customers to use their senses. Morrisons removed “use by” dates from most store-brand milk in January and replaced them with a “best before” label. Co-op, another grocery chain, did the same to its store-brand yogurts.

It’s a change some shoppers support. Ellie Spanswick, a social media marketer in Falmouth, England, buys produce, eggs and other groceries at farm stands and local shops when she can. The food has no labels, she said, but it’s easy to see that it’s fresh.

“The last thing we need to be doing is wasting more food and money because it has a label on it telling us it’s past being good for eating,” Spanswick said.

But not everyone agrees. Ana Wetrov of London, who runs a home renovation business with her husband, worries that without labels, staff might not know which items should be removed from shelves. She recently bought a pineapple and only realized after she cut into it that it was rotting in the middle.

“We have had dates on those packages for the last 20 years or so. Why fix it when it’s not broken?” Wetrov said.

Some U.S. chains — including Walmart — have shifted their store brands to standardized “best if used by” and “use by” labels. The Consumer Brands Association — which represents big food companies like General Mills and Dole — also encourages members to use those labels.

“Uniformity makes it much more simple for our companies to manufacture products and keep the prices lower,” said Katie Denis, the association’s vice president of communications.

In the absence of federal policy, states have stepped in with their own laws, frustrating food companies and grocers. Florida and Nevada, for example, require “sell by” dates on shellfish and dairy, and Arizona requires “best by” or “use by” dates on eggs, according to Emily Broad Lieb, director of the Food Law and Policy Clinic at Harvard Law School.

The confusion has led some companies, like Unilever, to support legislation currently in Congress that would standardize U.S. date labels and ensure that food could be donated to rescue organizations even after its quality date. At least 20 states currently prohibit the sale or donation of food after the date listed on the label because of liability fears, Lieb said.

Clearer labeling and donation rules could help nonprofits like Food Shift, which trains chefs using rescued food. It even makes dog treats from overripe bananas, recovered chicken fat and spent grain from a brewer, Apple said.

“We definitely need to be focusing more on doing these small actions like addressing expiration date labels, because even though it’s such a tiny part of this whole food waste issue, it can be very impactful,” Apple said.

__

Associated Press writers Kelvin Chan and Courtney Bonnell in London and Associated Press video journalist Terry Chea in Alameda, California contributed to this report.

'It doesn't mean you will get cancer': Carcinogen-free food is not easy to come by, experts say. How worried should consumers be?

ByRACHEL YEOOSCAR LIU

Laboratory tests commissioned by the Post have found several types of potentially cancer-causing chemicals in several popular snacks, and while experts say the risk to consumers is limited, they should pay close attention to their cooking methods, watch how much they eat of such products and consider diversifying their diets.

Ensuring food was completely free of carcinogens would prove difficult, some academics acknowledged, as the chemicals were often the result of high heat used during manufacturing or cooking. But consumers could take steps to minimise the risks, they said.

The checks, carried out by an established food testing laboratory, found 10 out of 18 samples of cooking oil, soy sauce, biscuits and crisps readily available on supermarket shelves contained types of cancer-causing substances.

But the tests all found lower levels of these harmful substances, namely glycidol, 3-MCPD (3-monochloropropane-1, 2-diol), acrylamide, arsenic and 4-methylimidazole, than what the Consumer Council recorded in its screenings carried out between 2016 and 2021.

Traces of glycidol, an organic compound, were detected in Quaker Oat Cookies with Raisins, Chips Ahoy Chocolate Chip Cookies Original and a sample of cooking oil, Yuwanjia Peanut Oil.

Most food safety guidelines, such as those from the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the Joint Food and Agriculture Organisation/World Health Organisation Expert Committee on Food Additives do not include recommended intake limits for glycidol.

While scientists have not determined what constitutes a dangerous amount of glycidol in food for humans, consuming any amount presented a risk, warned Chan Tsz-chung, a lecturer at the department of health and life sciences at the Hong Kong Institute of Vocational Education in Chai Wan.

PHOTO: South China Morning Post

"It doesn't mean you will get cancer, but it just increases the risks for it," he said.

But Dr Fong Lai-ying, an associate professor at the department of food and health sciences at the Technological and Higher Education Institute of Hong Kong, advised residents not to be too concerned, noting the total amount of glycidol present in 1kg of food samples measured in just micrograms. The chemicals were easily digested and degraded by the body, she added.

The commissioned tests found 103 micrograms per kilogram of glycidol in the sample of Chips Ahoy Chocolate Chip Cookies, less than the 570 micrograms per kilogram recorded by the council in 2019.

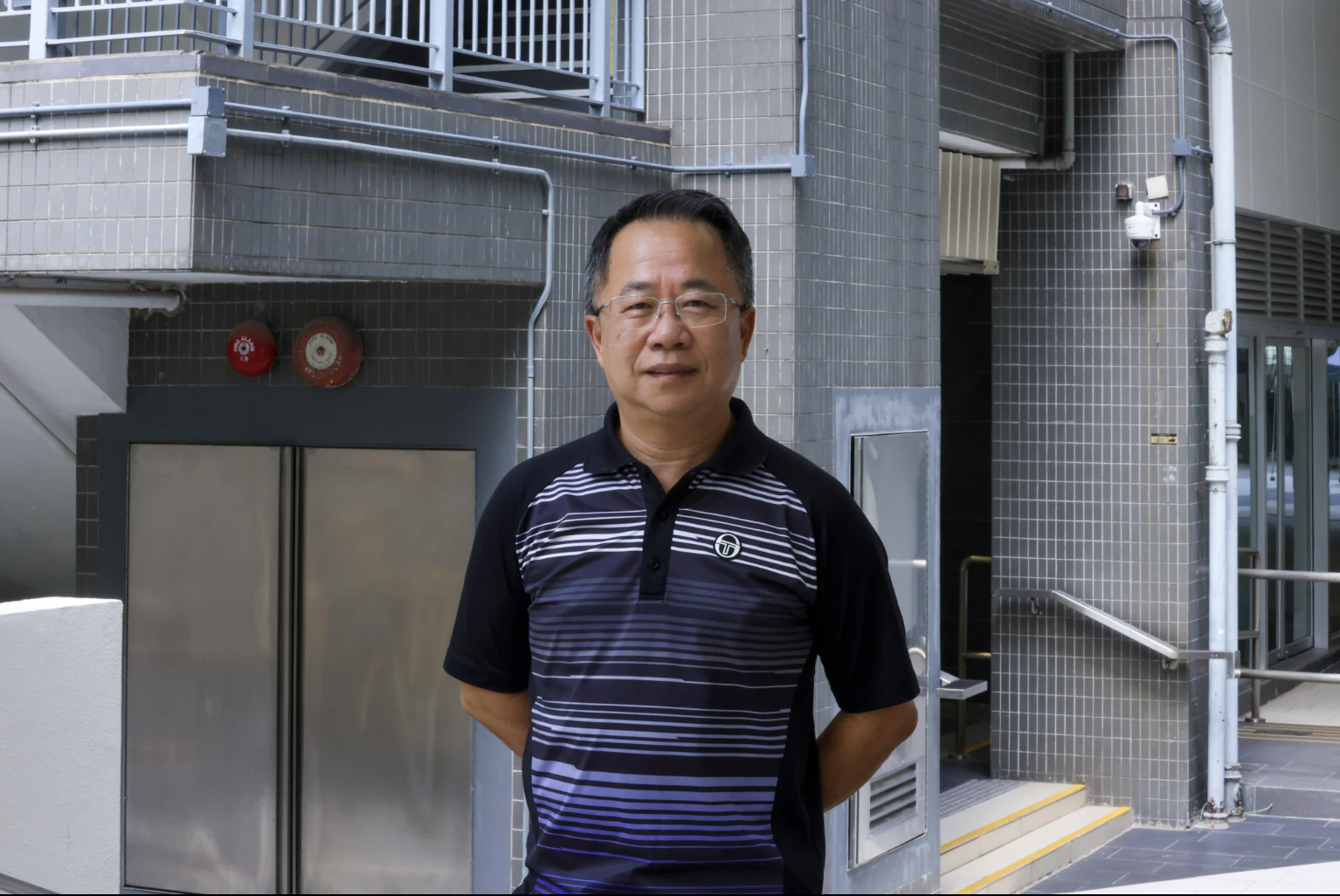

But 42-year-old father Lam Siu-ki, was unconcerned when told of the numbers. The biscuit brand was a family favourite, an inexpensive, convenient snack that could also be offered to guests, he said.

PHOTO: South China Morning Post

"These snacks are the best. They can be stored in my snack drawer for a long time," said the logistics worker, adding he was always on the lookout for deals when shopping for food for himself, his 37-year-old wife and their three-year-old daughter.

"My daughter and I can always munch on them when we are watching television or between meals," he said. "[The biscuits] are not expensive and taste pretty good. You can put them on a plate when guests visit. I love the fact that they are crunchy and not many brands have chocolate chips on top of the cookies."

Lam said he did not fret about consuming the carcinogens because he believed such chemicals were practically ubiquitous.

"You won't have choices if you are scared of the substance and ingredients in pre-packaged food. Chemical reactions are something you cannot control when it comes to food manufacturing," he said. "Even if that group [the council] can test every product on the market, people might still ignore its findings.''

Still, he conceded he would cut down on the number of the cookies his daughter ate.

A spokeswoman for the manufacturer, Mondelez Hong Kong, acknowledged the lab results but did not comment further.

PHOTO: South China Morning Post

The Post also tested Yuwanjia peanut oil and found it contained 417mcg/kg of glycidol and 380mcg/kg of 3-MCPD, an organic chemical compound and suspected carcinogen in humans that formed at high heat during the cooking process.

But again those levels marked an improvement over what the council found in 2017. It previously recorded 1,100mcg/kg of glycidol and 6,800mcg/kg of 3-MCPD.

Retiree Kam Mei-Lan, 71, who has two children and two grandchildren, said she had used Yuwanjia peanut oil and had no issues.

"I tend to use cooking oil generously when deep frying chips and nuggets for my grandchildren," she said. "The more oil I use for cooking, the better the smell of the food."

Kam lives in Tseung Kwan O, where several brands of cooking oil are available in nearby supermarkets such as ParknShop, Wellcome and U-Select, but she put price above all else when choosing which one to buy.

"I don't care about brands of cooking oil," she said. "It all depends on what supermarkets are closest to me or which brand is the cheapest."

A recent check in late August at stores run by the three chains in the neighbourhood found a pack of three 900mL bottles of Yuwanjia peanut oil cost HK$97.90 (S$17.80), while the same volume of the Lion and Globe brand and Yu Pin King one cost HK$104.90 and HK$100, respectively.

"There is nothing to be worried about," Kam insisted. "We just need oil for cooking. Any brand or even those imported ones could have bad stuff too. Affordability is one of my most important considerations."

But in a small concession to health perhaps, Kam has in the past few months started to use an air fryer to crisp up food, a cooking method that requires far less oil.

The Post presented the lab results to the manufacturer of Yuwanjia Peanut Oil, China Resources Vanguard (Hong Kong), and when asked for a comment it said the product was legal to sell locally.

The levels of 3-MCPD detected in the oil were still considered safe by experts, but the Centre for Food Safety advised residents to reduce their exposure to the compound and glycidol by cutting consumption of refined fats and oils, as well as related products, such as margarine.

Similarly, the government department advised food companies to follow the relevant industry code of practices contained in the Codex Alimentarius to ensure levels of 3-MCPD and glycidol in edible fats and oils were reduced as much as possible.

The Codex is a collection of international standards and guidelines to protect consumer health and ensure fair practices in the food trade, with the suggestions widely adopted around the world.

One way consumers can protect themselves is by keeping the heat low when cooking with oil, according to Fong at the Technological and Higher Education Institute. She recommended that when cooking food in oil, the heat be less than 150 degrees Celsius. A spokesman for the centre advised the public not to cook food at high temperatures for too long.

The Post also found small amounts of acrylamide, another organic compound, in four food product samples: Luke's Organic White Truffle & Sea Salt Potato Chips, Marks & Spencer All Butter Cookies with Pistachio Nuts and Almonds, Wise Cottage Fries Potato Chips Hot & Spicy Flavour and Nissin Koikeya Karamucho Hot Chilli Flavour Potato Chips.

The United States Department of Health considers acrylamide to be "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen", but experts such as Fong and Chan said the levels found in the lab tests were still safe to consume. Acrylamide, which is also found in cigarette smoke, can be an unintentional by-product of cooking certain foods at high temperature.

Consumers can choose to boil or steam instead to reduce the formation of acrylamide, Fong said, adding they should closely follow the manufacturer's instructions on the package to avoid overcooking.

"All these carcinogens are not added purposely by the manufacturers, they will come naturally throughout the cooking process with high temperatures," she said. "It's very difficult to avoid or reduce them to zero.

"It is better to have guidelines than to have a law that stops the production of these types of carcinogens in those foods."

PHOTO: South China Morning Post

Thomas Ng Wing-yan, chairman of the Hong Kong Food Council, shared a similar opinion, saying there was only "relative safety, but not absolute safety".

"Even if you are careful about what you eat, it doesn't mean if you buy one product over the other then you are considered safe. It's not possible because everything has substances, so does that mean you don't eat at all?" he said.

Experts noted that people's bodies absorb certain chemicals at different rates, and the level depends on physical fitness and other health factors, making it difficult to establish a universal standard that could be recommended for everyone.

Ng advised residents to eat in moderation and alter the variety of foods consumed – coffee one day and apple or orange juice the next, for example.

PHOTO: South China Morning Post

The Post also examined the level of sodium in three crispy snacks. The product with the highest amount was Select Original Prawn Crackers with 1,400 milligrams per 100 grams of sodium, up slightly from the 1,320 milligrams per 100 grams detected by the council two years ago.

The other two crispy snacks, Brilliant Hot & Spicy Flavour Prawn Crackers and Papatonk Original Indonesian Premium Shrimp Crackers, had 1,260 milligrams per 100 grams and 1,090 milligrams per 100 grams, slightly higher than what the watchdog found in August 2020.

But Fong said the elevated sodium levels should not be a cause for concern among most adults, as they generally did not eat such snacks regularly. But parents should monitor how many salty snacks their children consumed, she warned, as they might have less self-control and binge.

She advised manufacturers to offer their snacks in smaller sizes, such as selling 20 gram portions instead of 100 gram packets, so consumers could more easily regulate their sodium intake.

According to the centre, adults should consume no more than 2,000 milligrams of sodium daily to reduce the risk of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke and coronary heart disease. Consumers are also advised to read the nutrition labels when buying pre-packaged food and choose ones with less sodium.

This article was first published in South China Morning Post.

No comments:

Post a Comment