TORIES CANNOT MANAGE CAPITALI$M

Pound falls again as agency downgrades outlook for UK's credit rating to 'negative'

Fitch takes aim at the apparent conflict between government policy and Bank of England action to fight inflation, warning that it is concerned by the levels of borrowing the chancellor is likely to need to fund the growth plan.

James Sillars

Business reporter @SkyNewsBiz

Thursday 6 October 2022

Fitch takes aim at the apparent conflict between government policy and Bank of England action to fight inflation, warning that it is concerned by the levels of borrowing the chancellor is likely to need to fund the growth plan.

James Sillars

Business reporter @SkyNewsBiz

Thursday 6 October 2022

Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng is due to meet bank bosses on Thursday

A measure of confidence in the UK's creditworthiness has been slashed by another major ratings agency in the wake of the mini-budget, piling further pressure on the under-fire pound.

Fitch revealed on Wednesday night that it had cut the outlook for its credit rating on UK government debt to "negative" from "stable".

It maintained its overall rating - with AAA being the ideal verdict - at AA-.

The shift reflected, it said, mounting concern over the level of borrowing required to fund the chancellor's tax and spending pledges made in the Commons last month.

Financial markets delivered a stinging verdict on the package, dubbed a growth plan by Kwasi Kwarteng, with sterling eventually plunging to an all-time low against the dollar.

Investors also demanded higher rates of return for holding UK government debt, with the Bank of England later intervening to buy long-dated bonds to prevent a crisis for pension funds.

A series of U-turns have since helped the pound and bond yields recover some poise.

Truss: ‘No shame’ over tax U-turn

The UK currency was, however, trading back towards $1.13 on Thursday morning though that partly reflected a rekindling of dollar strength after further oil market turbulence.

Fitch revealed its decision days after a similar move by rival Standard & Poor's.

It said of the chancellor's mini-budget: "The large and unfunded fiscal package announced as part of the new government's growth plan could lead to a significant increase in fiscal deficits over the medium term."

The agency hit out at the lack of independent budget forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the statement and the policy clash that sees the government trying to grow the economy at a time when the Bank of England is trying to shrink demand in its fight against inflation.

It added: "Although the government reversed the elimination of the 45p top rate tax... the government's weakened political capital could further undermine the credibility of and support for the government's fiscal strategy."

Sky News revealed on Wednesday that Mr Kwarteng was due to meet bank bosses on Thursday amid concerns about the impact of the recent market turmoil on home loan provision.

It has emerged that the average mortgage interest rate has risen to above 6%, meaning households are paying the greatest portion of their income on mortgage payments since 1989 - exacerbating the wider cost of living crisis.

A measure of confidence in the UK's creditworthiness has been slashed by another major ratings agency in the wake of the mini-budget, piling further pressure on the under-fire pound.

Fitch revealed on Wednesday night that it had cut the outlook for its credit rating on UK government debt to "negative" from "stable".

It maintained its overall rating - with AAA being the ideal verdict - at AA-.

The shift reflected, it said, mounting concern over the level of borrowing required to fund the chancellor's tax and spending pledges made in the Commons last month.

Financial markets delivered a stinging verdict on the package, dubbed a growth plan by Kwasi Kwarteng, with sterling eventually plunging to an all-time low against the dollar.

Investors also demanded higher rates of return for holding UK government debt, with the Bank of England later intervening to buy long-dated bonds to prevent a crisis for pension funds.

A series of U-turns have since helped the pound and bond yields recover some poise.

Truss: ‘No shame’ over tax U-turn

The UK currency was, however, trading back towards $1.13 on Thursday morning though that partly reflected a rekindling of dollar strength after further oil market turbulence.

Fitch revealed its decision days after a similar move by rival Standard & Poor's.

It said of the chancellor's mini-budget: "The large and unfunded fiscal package announced as part of the new government's growth plan could lead to a significant increase in fiscal deficits over the medium term."

The agency hit out at the lack of independent budget forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the statement and the policy clash that sees the government trying to grow the economy at a time when the Bank of England is trying to shrink demand in its fight against inflation.

It added: "Although the government reversed the elimination of the 45p top rate tax... the government's weakened political capital could further undermine the credibility of and support for the government's fiscal strategy."

Sky News revealed on Wednesday that Mr Kwarteng was due to meet bank bosses on Thursday amid concerns about the impact of the recent market turmoil on home loan provision.

It has emerged that the average mortgage interest rate has risen to above 6%, meaning households are paying the greatest portion of their income on mortgage payments since 1989 - exacerbating the wider cost of living crisis.

The politics of Britain’s ‘mini-budget’ crisis

By Andrew Curry,

originally published by thenextwave

October 5, 2022

Resilience

Building a world of resilient communities

To borrow Hemingway’s famous phrase, political and economic crises happen gradually, then suddenly. And when they do happen suddenly, there are lots of immediate reasons why. The current economic and political crisis in the UK is largely self-inflicted, which raises the question of ‘why?’, but can also be thought of as representing the endgame of a long political wave.

No, you can’t know when the actual moment will be. But over a long period of time, the options keep narrowing until there are no good choices left, at least for the party and politicians that have benefited from that wave. Every political party hits a zugzwang moment.

Forty year cycles

I think it was the politics academic David Runciman who observed that if you looked back over a century of British politics, you could see cycles that ran from economic crisis to economic crisis every forty years or so, with a political settlement coming around a decade later. I can’t find the source for that, though.

This is a heuristic, not a law, and the timings are approximate. But, indicatively, the long depression of the late 19th century ran to 1896 (with Baring’s Bank bailed out in 1890); the 1929 crash led to the depression of the 1930s; the oil crisis happened in 1973-74; and, then of course, there was the 2008 crash.

The political effects of these: the ‘Liberal landslide’ of 1906, the Labour win in 1945 (complicated by the experience of war), Thatcher’s win in 1979 and subsequent victories in 1983 and 1987. And the 2008 crisis is still playing out in our politics today.

Systems patterns

It happens that you see this two-generation pattern in other bits of the literature. Strauss and Howe’s idea of the ‘Fourth Turning’ basically proposes a four-generation model from crisis to crisis. Their four generation pattern more or less goes ‘build’/‘enjoy’/‘exploit’/‘unravel’, although that’s not the language they use. It follows a classic long-run systems pattern, even if some of their post-hoc timings are spuriously exact.

All the same, the mechanism is visible. A crisis leads to a system reset, designed to solve the problems that caused the crisis. For a generation you get a reinforcing loop as the system benefits from this new set of ideas. But all systems decay over time, and a balancing loop kicks in as the problems caused by those new ideas come to the fore.

The advocates of the previous set of reforms retire or die off, and a set of ideas that had some coherence to them either become incoherent, or simply no longer fit the changing political and economic landscape. As David Muir noted, Thatcher said this explicitly of the Labour Party back then:

He added:

Now applies to the Conservative Party.

Conservative decline

So the current British political and economic crisis can be seen as the last twitch of Thatcherism, and by two of its last remaining zealots. I’ll be coming back to the-budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget later in this piece, but there’s another important element here. This is about the long-term decline and de-composition of the Conservative party.

I know this is a strong thing to say. We’re talking about a party that has a majority of 80 seats in the British House of Commons, and one of the givens of modern British politics is that you should never bet against the Conservative party. Over the last century it has been the most successful ruling party in Europe.

But it has been unravelling since the 1980s. In the 1950s, and the era of ‘One Nation’ Conservatism, the Conservative Party was also a social institution, with 2.5 million members across Britain. (In Barnet, in north London, which had 70,000 voters, there were 12,000 Conservative party members. By the 2000s, its membership was less than a tenth of this, and ageing fast. Social values had moved away from the party as well. Economics, which have punished the younger generation, means that the party’s vote is now heavily skewed towards the over-60s and the party’s policies have followed.

Triangulation

David Cameron’s attempted solution to this was to triangulate: a pretence at ‘one nation’ social values to voters (gay marriage and ‘hug a hoodie’), with the party funds coming from an increasingly narrow base within the finance sector, and the core vote shored up with a message that drifted between patriotism and racism.

The first part of that was sheered off by UKIP and the Brexit, while the finance base got narrower (Johnson’s “fuck business” moment in Brussels was emblematic) but Johnson propped it up for a moment with the idea of ‘levelling up’, which appealed to enough voters beyond the traditional Conservative base to win an election. If you’re interested in the political sociology of all of this, the most persistent analyst is the sociologist Phil Burton-Cartledge at his ‘All That Is Solid’ blog—for example in these 2018 pieces—and in his book on the post-war history of the Conservative Party.

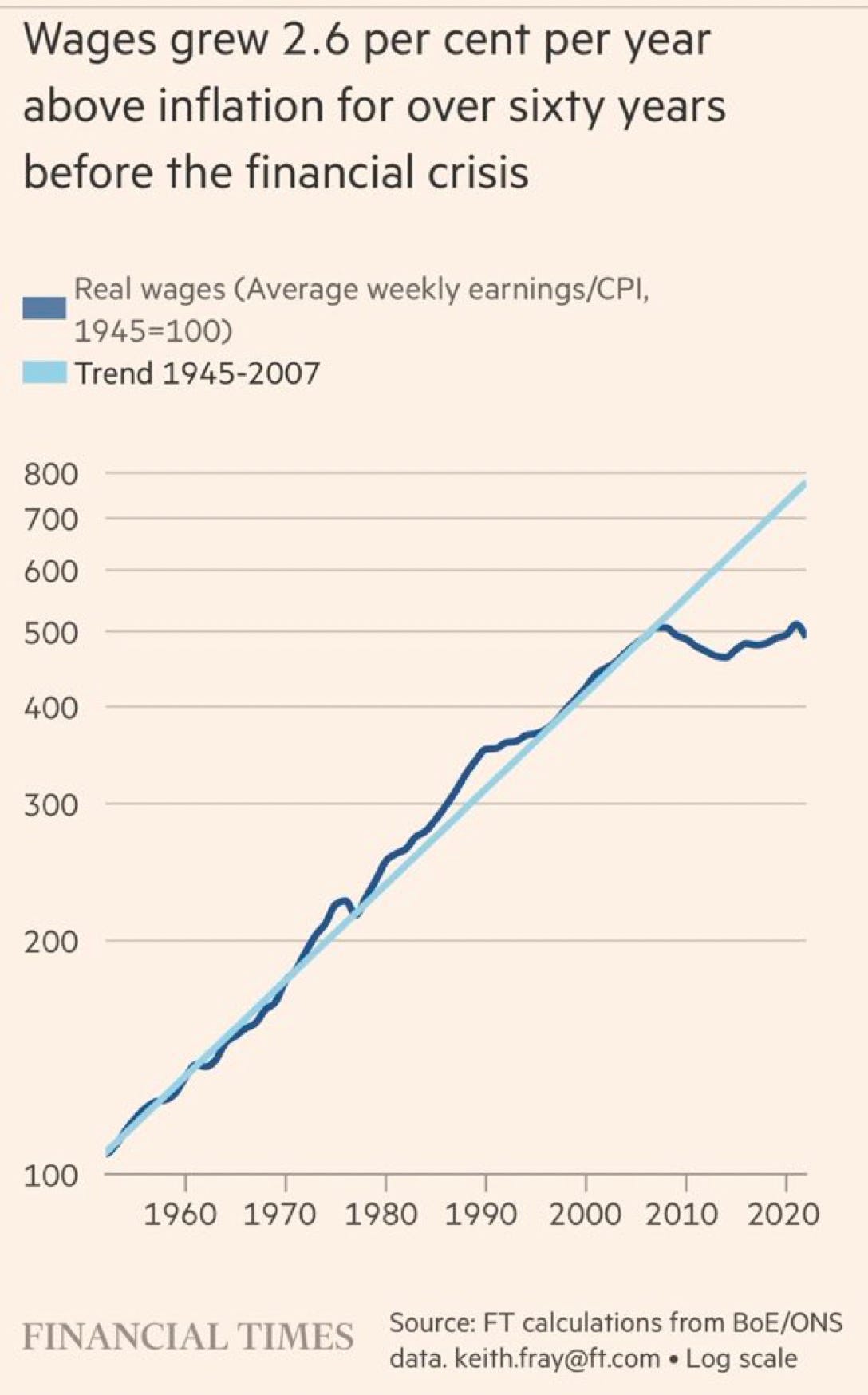

Levelling up was an interesting idea, or would have been had the Conservatives treated it as a strategy and not a slogan. At the least it could have been a programme that dealt with Britain’s real problem, which is captured sharply in a chart from the Financial Times a few weeks ago.

(Britain’s wage and productivity problem. Source: Financial Times)

Flat wage growth

The problem is this: wage growth, and associated productivity, in the UK have been flat since the financial crisis. The causes of this are either complicated, which is the version you get from economists, or they are post-crisis austerity, which killed off the initial post-crisis recovery, followed by Brexit, which had a calamitous effect first on business investment and then on trade.

These together have created the low wage, low investment economy that has characterised Britain recently, with a toxic combination of flat wages and low investment. Paul Mason explained how this worked in practice in a Guardian article a few years ago by using hand-washed car businesses as an example.

And one of the sharper observations on Twitter when inflation started picking up (you can never find a Tweet when you need one) was by James Meadway, who suggested that this low wage, low investment economy also needed low inflation and low interest rates to survive.

Doing something

But for a moment, let’s take the so-called ‘mini-Budget’ at face value. If the rise in inflation and interest rates has wrecked the UK’s low-wage, low-interest rate economy, then the government had to do something.

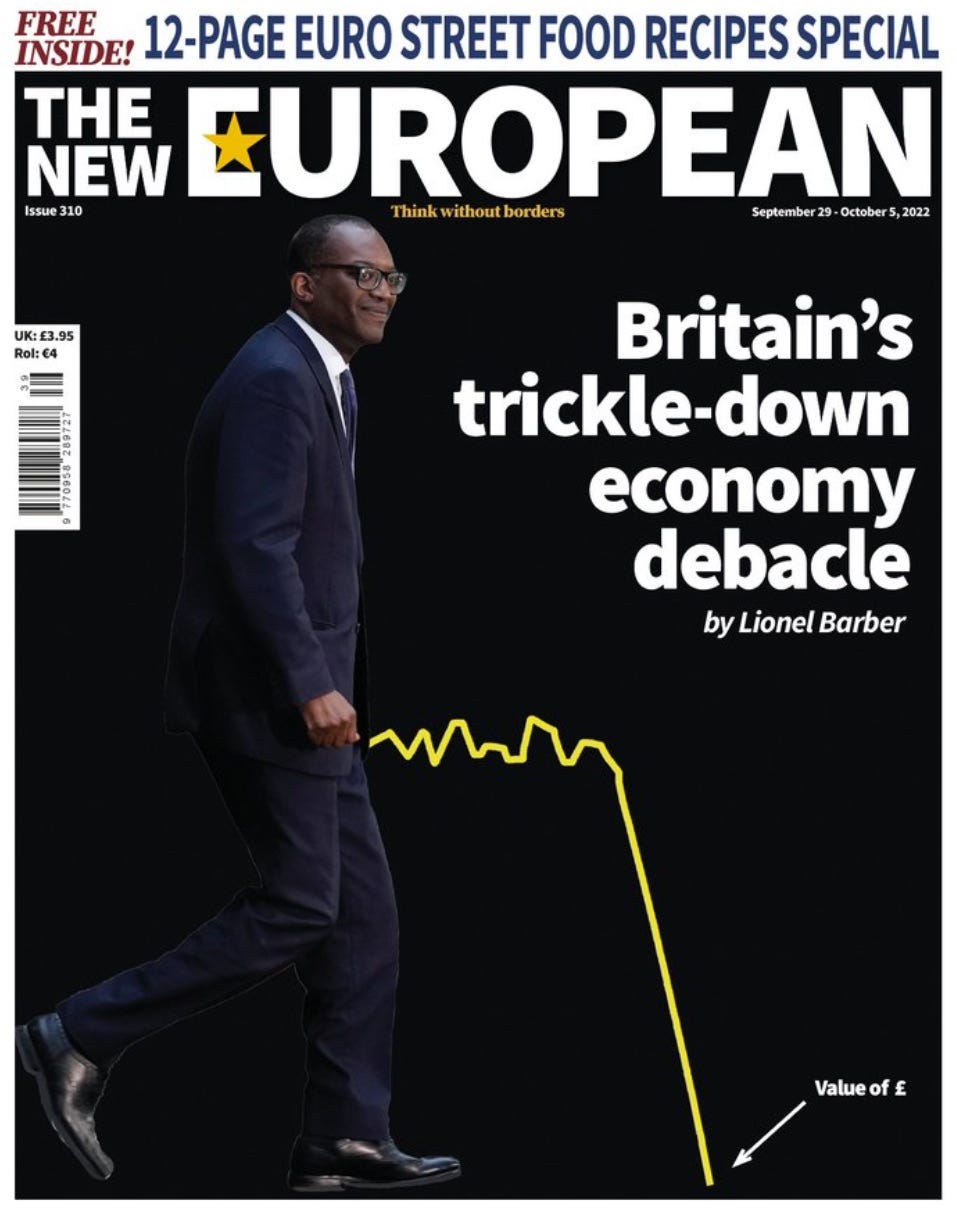

So, if you want to be generous to the budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget, you can say that it was, as claimed, an attempt to do something about productivity. I’ll pretend for a moment that Truss and Kwarteng were being honest when they said it was a ‘budget’ about growth.

But even this hits an immediate problem. In the 1980s, the idea of trickle-down economics and the Laffer Curve was contested, to say the least, but hadn’t been disproved. Similarly, ‘freeports’ and all of the other mechanisms of supply side economics had not yet been discredited. They represented then part of a suite of theories about how to solve the problems of the previous economic model. But everyone knows that’s no longer true. 40 years on, these are burnt out ideas that don’t work in the way their advocates thought they would.

Eric Beinhocker and Nick Hanauer spelt out some of the issues in an article in The Guardian:

As Truss put it last week: “Lower taxes lead to economic growth, there is no doubt in my mind about that.” There may be no doubt in the prime minister’s mind, but there’s a lot of doubt in the data. The US has had four decades experimenting with this kind of economics, and the evidence is clear: not only does it not work but it does enormous damage to the economy and society.

Understanding the government

So what’s going on with our new administration? I think there are four alternatives.

1. They are zealots who don’t realise that the ideas they have believed in for decades are no longer fit for purpose.

2. Or they are working a clever plan to create a crisis to force further cuts in the size of the state and of public spending.

3. Or they realise that they are only going to get one shot at this, and they have decided to help their friends and political supporters cash in before the house comes crashing down around their ears. (Corruption, in other words).

4. Or they aren’t very good at politics.

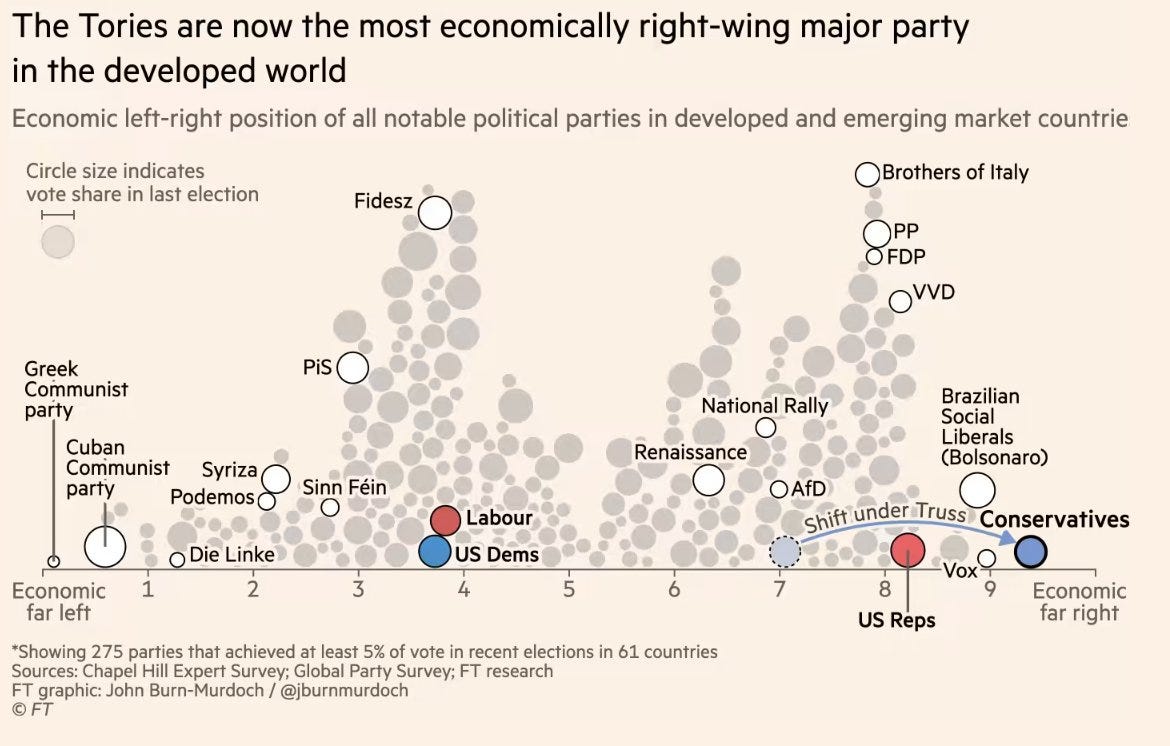

Measuring ‘zealotry’ is hard, even though you know it when you see it, and usually people just point to the libertarian economic manifesto, Britannia Unchained, that Truss, Kwarteng and others co-authored a decade ago. But while I was writing this piece, the Financial Times’ data journalist John Burn-Murdoch published a handy chart mapping economic policies by political party across a number of countries.1 The policies of the current Conservative administration are now right at the edge of the scale, having shifted from the centre-right mainstream to the right under Truss (‘jumped’ or ‘lurched are more accurate descriptions).

(Source: Financial Times)

Heady cocktail

Of course, some of the evidence fits several of these interpretations. Firing the head of the British Treasury department and then declaring that your Budget is a ‘mini-budget’, to avoid scrutiny, could be zealotry, or it could be cashing in, or it could be incompetence.

It’s probably doesn’t go with the ‘clever plan’ version, though, since the Treasury went along with years of Osborne’s austerity without kicking up a fuss despite the economic damage it was causing. (There are other views on the ‘clever plan’.)

My own view, briefly, is that it’s a heady cocktail of zealotry, corruption, and incompetence—that all three have interacted with each other to create the current crisis. You could even say that the current crisis is over-determined, because any two of these would have been enough.

Corruption

It is impossible to avoid the smell coming from the British government at the moment: the Chief of Staff who is of interest to the FBI, the Conservative billionaire hedge fund owner and Conservative donor Crispin Odey who used to employ the Chancellor who has made millions shorting the pound as a result of its collapse following the budget—with just a sniff of private information beforehand. Odey seems to have salvaged the fortunes of his hedge fund by doing this. Not to mention the Cabinet Minister and former (briefly) Chancellor of the Exchequer whose possible tax avoidance scheme continues to raise questions.

This list could go on, but it’s been a theme of the 2019 ‘Brexit’ government. The same corruption was seen throughout the pandemic procurement scandals.

As for competence, one of the signs of decline of a party is a shrinking pool of talent. The political talent pool has been shrunk more generally by the professionalisation of politics, but the Conservatives have accelerated this through expelling some MPs and by pushing through its pursuit of their ideological version of Brexit.

Running the country

In The Critic, Mike Jones brought these two ideas together when he noted a few months ago the shallowness of much of the Conservative leadership campaign:

For (leadership candidate Kemi) Badenoch, modern-day Conservatism is pretty much hollowed out, at least in terms of policy…“What’s missing”, she wrote, “is an intellectual grasp of what is required to run the country.” While Labour is cementing its image as the party of productivity and investment, the Tories, though unintentionally, spend much of its efforts in making the party as unattractive as possible.

But the deeper problem is that the party’s underlying ideas—legacies of that 40-year wave I discussed on Saturday—are about a smaller state with less public capacity. Hence Jacob Rees-Mogg’s persistent desire to shrink the civil service. A decade of austerity has stretched the capability of the state, of public services, and of local authorities to close to collapse.

State capacity

And one of the things we have learned, from the pandemic, from the climate crisis, and from the energy crisis, is that states need capacity if they are going to offer any kind of security to their citizens. Markets alone can not deliver this, even if they are well regulated. And they can no longer deliver growth either: we know, from the work of Mariana Mazzucato and others, that this requires all kinds of investment in public capacity.

Beinhocker and Hanauer described this as “middling out” economics, and it requires public investment:

a robust economy of thriving middle-income families is not a consequence of economic growth, it is its cause. So the policy priority is then to invest in the broad population of working people: education, healthcare, childcare, elderly care, worker training, affordable housing and good public infrastructure, from transport to broadband. It is also critical to support people with a living minimum wage and enough economic security that they aren’t economically trapped and can take risks, from starting a new business, to taking time out to reskill.

Johnson’s maverick style allowed him to nod in the direction of all of this, at least rhetorically, even if he had little intention of doing it. The political effect of Kwasi Kwarteng’s budget for the rich, along with Truss’ belated conversion to energy support, and the rolling crises that followed it, was to make voters realise viscerally—almost in a single day—how much they need the state to be on their side, to look after their security, in the 2020s.

A version of this article was published in two parts on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

By Alasdair Sandford • Updated: 05/10/2022

Britain's Prime Minister Liz Truss makes a speech at the Conservative Party conference at the ICC in Birmingham, England, Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2022. - Copyright AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth

"I have three priorities for our economy: growth, growth and growth."

The concept formed the centrepiece of Liz Truss' speech to the Conservative Party conference, and the new British prime minister mentioned the word more than two dozen times.

"For too long, our economy has not grown as strongly as it should have done," Truss said. She underlined the importance of growth to the UK economy by linking it to the need to cut taxes — "putting up a sign that Britain is open for business" — slash regulation, boost investment, and improve public services.

Castigating "those who try to stop growth", she vowed she would "not allow the anti-growth coalition to hold us back".

And she painted Brexit in entirely positive terms, saying the government was "seizing the new-found freedoms outside the European Union", and "making the most of the huge opportunities Brexit offers".

Yet several reports say one significant factor to have impacted negatively on Britain's growth and economy — also creating a barrier to future performance — is Brexit itself.Liz Truss speech: Five key takeaways including Greenpeace, Brexit and 'facing down separatists'

Post-2016 period: After the UK voted to leave the EU

Some surveys have said the vote for Brexit in the June 2016 referendum had a damaging effect on the British economy, even before the UK actually left the EU and its economic structures.

"Voting for Brexit had large negative effects on the UK economy between 2016 and 2019, leading to higher import and consumer prices, lower investment, and slower real wage and GDP growth", wrote two economists from the London School of Economics (LSE) in a paper for the think-tank UK in a Changing Europe, published this year.

This happened even though at this stage "there was little or no trade diversion away from the EU", the report said.

Another report by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) reached a similar conclusion. "Even before Brexit has actually taken place, the referendum shock of June 2016 has already had substantial economic costs," its study said in March 2020, updating its previous analysis from three years earlier.

"We estimate that the Brexit depreciation increased UK consumer prices by 2.9%. This represents an £870 per year increase in the cost of living for the average UK household," its four authors said.

An assessment by Investment Monitor in January 2022 found that UK growth trailed that of leading European counterparts in the years following the Brexit vote, even though it had been ahead at the start of 2015, and again at the time of the 2016 referendum.

"Based on figures from the OECD, UK GDP grew by 14.3% between Q2 2016 and Q3 2021. This is a smaller growth rate than four of the EU’s largest economies. During the same period, Germany had the highest indexed growth rate at 32.2%, followed by Spain (25.6%), France (23%) and Italy (16.3%)," it said.

"In the post-referendum and pre-TCA period, the economic effects of Brexit began to materialise. Products more exposed to the uncertainty of future trading relations with the EU experienced lower trade growth," said another report by LSE researchers for UK in a Changing Europe, published in April 2022.

It also concluded that increased UK-EU trade barriers had caused UK food prices to rise by six percent between the end of 2019 and September 2021 compared to the years before December 2019.

Brexit Timeline 2016–2020: key events in the UK’s path from referendum to EU exit

Post-2021: After Brexit took effect

This year has seen economists begin to separate the economic damage done by Brexit from that wrought by the COVID pandemic.

In June a report by John Springford of the Centre for European Reform (CER) estimated that in the final quarter of 2021, GDP (gross domestic product) was 5.2% smaller, investment 13.7% lower, and goods trade 13.6% lower than what they would have been had the UK remained in the EU.

He added that tax rises imposed by Boris Johnson's then government " would not have been needed if the UK had stayed in the EU (or in the single market and customs union)".

Two other reports cast a shadow over Liz Truss' desire to advertise Britain as "open for business".

The UK's Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) reported in March that the UK had "missed out on much of the recovery in global trade," amid the recovery from the pandemic, noting that the UK "appears to have become a less trade intensive economy".

"The Big Brexit" published in June by the Resolution Foundation think-tank and the LSE found that a drop in British "trade openness" — measured as a share of GDP — showed a much higher fall than in countries with similar trade profiles, such as France.

In May a report by the Peterson Institute for Economics found that Brexit was "driving inflation in the UK higher than its European peers", despite suffering the same economic shocks from Russia's war on Ukraine and soaring energy prices. It blamed in particular labour shortages resulting from the end of the free movement of EU migrant workers to the UK, as well as new trade barriers.

In September City A.M. reported that the number of UK businesses exporting to the EU had fallen by a third in 2021 compared to 2020, due to the extra red tape they faced when trading with the bloc. It quoted figures from the UK's Revenue and Customs department HMRC.

An earlier study by the LSE, from April, found that Brexit caused "major disruption" to both EU-UK exports and imports, with many British firms stopping trade with the EU.

Eurostat data on EU trade with the UK published in March said goods imports from the UK to the EU in 2021 declined by nearly a quarter relative to 2019, while the value of services imports from the UK fell by nearly 7% over the same period.

The UK left the EU at the end of January 2020, and the new rules came into force when a transition period expired on December 31 that year. Its departure from the EU's single market and customs union, and the trade deal negotiated by then prime minister Boris Johnson, created significant barriers to trade with the bloc.Brexit damage: Is EU exit now hitting UK's economy harder than COVID?

Brexit agreement caused 'major disruption' to EU-UK trade, finds study

For both Conservatives and Labour, Brexit is done

Both the UK's ruling party and main opposition agree that there is no going back on Brexit.

"We are the party who got Brexit done," trumpted Liz Truss in her conference speech in Birmingham.

In a speech in July, Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said he "couldn't disagree more" with those who wanted Brexit reversed — instead offering a new slogan of "Make Brexit Work".

There are understandable political imperatives behind such stances, and they may explain why Brexit often features little in debates over the UK's current economic plight.

But many critics of the government and opposition alike say the failure to face up to the reality of the UK's EU exit — and the barriers created with its closest trading partner — mean the complexities of the situation are not being properly understood.

Britain's Prime Minister Liz Truss makes a speech at the Conservative Party conference at the ICC in Birmingham, England, Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2022. - Copyright AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth

"I have three priorities for our economy: growth, growth and growth."

The concept formed the centrepiece of Liz Truss' speech to the Conservative Party conference, and the new British prime minister mentioned the word more than two dozen times.

"For too long, our economy has not grown as strongly as it should have done," Truss said. She underlined the importance of growth to the UK economy by linking it to the need to cut taxes — "putting up a sign that Britain is open for business" — slash regulation, boost investment, and improve public services.

Castigating "those who try to stop growth", she vowed she would "not allow the anti-growth coalition to hold us back".

And she painted Brexit in entirely positive terms, saying the government was "seizing the new-found freedoms outside the European Union", and "making the most of the huge opportunities Brexit offers".

Yet several reports say one significant factor to have impacted negatively on Britain's growth and economy — also creating a barrier to future performance — is Brexit itself.Liz Truss speech: Five key takeaways including Greenpeace, Brexit and 'facing down separatists'

Post-2016 period: After the UK voted to leave the EU

Some surveys have said the vote for Brexit in the June 2016 referendum had a damaging effect on the British economy, even before the UK actually left the EU and its economic structures.

"Voting for Brexit had large negative effects on the UK economy between 2016 and 2019, leading to higher import and consumer prices, lower investment, and slower real wage and GDP growth", wrote two economists from the London School of Economics (LSE) in a paper for the think-tank UK in a Changing Europe, published this year.

This happened even though at this stage "there was little or no trade diversion away from the EU", the report said.

Another report by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) reached a similar conclusion. "Even before Brexit has actually taken place, the referendum shock of June 2016 has already had substantial economic costs," its study said in March 2020, updating its previous analysis from three years earlier.

"We estimate that the Brexit depreciation increased UK consumer prices by 2.9%. This represents an £870 per year increase in the cost of living for the average UK household," its four authors said.

An assessment by Investment Monitor in January 2022 found that UK growth trailed that of leading European counterparts in the years following the Brexit vote, even though it had been ahead at the start of 2015, and again at the time of the 2016 referendum.

"Based on figures from the OECD, UK GDP grew by 14.3% between Q2 2016 and Q3 2021. This is a smaller growth rate than four of the EU’s largest economies. During the same period, Germany had the highest indexed growth rate at 32.2%, followed by Spain (25.6%), France (23%) and Italy (16.3%)," it said.

"In the post-referendum and pre-TCA period, the economic effects of Brexit began to materialise. Products more exposed to the uncertainty of future trading relations with the EU experienced lower trade growth," said another report by LSE researchers for UK in a Changing Europe, published in April 2022.

It also concluded that increased UK-EU trade barriers had caused UK food prices to rise by six percent between the end of 2019 and September 2021 compared to the years before December 2019.

Brexit Timeline 2016–2020: key events in the UK’s path from referendum to EU exit

Post-2021: After Brexit took effect

This year has seen economists begin to separate the economic damage done by Brexit from that wrought by the COVID pandemic.

In June a report by John Springford of the Centre for European Reform (CER) estimated that in the final quarter of 2021, GDP (gross domestic product) was 5.2% smaller, investment 13.7% lower, and goods trade 13.6% lower than what they would have been had the UK remained in the EU.

He added that tax rises imposed by Boris Johnson's then government " would not have been needed if the UK had stayed in the EU (or in the single market and customs union)".

Two other reports cast a shadow over Liz Truss' desire to advertise Britain as "open for business".

The UK's Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) reported in March that the UK had "missed out on much of the recovery in global trade," amid the recovery from the pandemic, noting that the UK "appears to have become a less trade intensive economy".

"The Big Brexit" published in June by the Resolution Foundation think-tank and the LSE found that a drop in British "trade openness" — measured as a share of GDP — showed a much higher fall than in countries with similar trade profiles, such as France.

In May a report by the Peterson Institute for Economics found that Brexit was "driving inflation in the UK higher than its European peers", despite suffering the same economic shocks from Russia's war on Ukraine and soaring energy prices. It blamed in particular labour shortages resulting from the end of the free movement of EU migrant workers to the UK, as well as new trade barriers.

In September City A.M. reported that the number of UK businesses exporting to the EU had fallen by a third in 2021 compared to 2020, due to the extra red tape they faced when trading with the bloc. It quoted figures from the UK's Revenue and Customs department HMRC.

An earlier study by the LSE, from April, found that Brexit caused "major disruption" to both EU-UK exports and imports, with many British firms stopping trade with the EU.

Eurostat data on EU trade with the UK published in March said goods imports from the UK to the EU in 2021 declined by nearly a quarter relative to 2019, while the value of services imports from the UK fell by nearly 7% over the same period.

The UK left the EU at the end of January 2020, and the new rules came into force when a transition period expired on December 31 that year. Its departure from the EU's single market and customs union, and the trade deal negotiated by then prime minister Boris Johnson, created significant barriers to trade with the bloc.Brexit damage: Is EU exit now hitting UK's economy harder than COVID?

Brexit agreement caused 'major disruption' to EU-UK trade, finds study

For both Conservatives and Labour, Brexit is done

Both the UK's ruling party and main opposition agree that there is no going back on Brexit.

"We are the party who got Brexit done," trumpted Liz Truss in her conference speech in Birmingham.

In a speech in July, Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said he "couldn't disagree more" with those who wanted Brexit reversed — instead offering a new slogan of "Make Brexit Work".

There are understandable political imperatives behind such stances, and they may explain why Brexit often features little in debates over the UK's current economic plight.

But many critics of the government and opposition alike say the failure to face up to the reality of the UK's EU exit — and the barriers created with its closest trading partner — mean the complexities of the situation are not being properly understood.

No comments:

Post a Comment