Why Is Anti-Americanism in Russia Less Widespread Now Than in 2014?

Amid the current Russian-Ukrainian conflict, in which Washington has firmly taken Kyiv’s side, Russian public opinion toward America has deteriorated, as might be expected. But anti-Americanism in Russia has stayed below its peak values of 2014-2015, when the U.S. condemned and sanctioned Moscow for its annexation of Crimea and military support for separatists in Ukraine’s east. Why?

Based on regularly conducted research by the Levada Center, at least three interrelated factors may help explain: First, negative attitudes toward the U.S. have been widespread for at least eight years, fluctuations notwithstanding, so U.S. policies perceived as aimed against Russia may simply seem like more of the same; second, younger audiences who get their news online have greater exposure to independent and/or pro-Western voices than they did just a few years ago; and, third, is the possibility that peak anti-Americanism is still ahead of us.

Though today’s confrontation between Russia and the United States is clearly more acute than eight years ago, the current trend in public opinion has followed a similar trajectory as before, with the share of Russians holding negative views of the U.S. rising from 42% in November 2021 to 75% in May 2022 (and inching down to 71% in August).

Of course, Russian anti-Americanism is a complex phenomenon, and should not be reduced to only one indicator. For instance, even when overall attitudes toward the U.S. were positive, there was significant distrust toward American foreign policy. At the same time, attitudes toward ordinary Americans have always been much more positive than toward the U.S. as a country. Even now about half of Russians have a positive view of the American people, differentiating between the U.S. establishment and ordinary Americans. And yet “attitudes toward the U.S. as a country” is what we ask about several times a year, so this is the indicator for which we have the most data.

Caveats notwithstanding, I believe that polling in Russia is still informative. For one thing, it gives a basis for comparison: Thus far, the response rate for our surveys hasn’t changed much since February. Also, our additional research does not back up assertions that people who do not approve of the country’s leadership are more likely to refuse to take part in a poll or that polls only represent people who are prepared to engage and answer questions.

Anti-Americanism as the New Normal

Our polls show that in recent years anti-Americanism in Russia has become the new normal. Up until 2014, positive feelings toward America generally prevailed. There were only relatively short bursts of anti-Americanism: during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Russian-Georgian war in 2008, when the U.S. also sided with Moscow’s adversary. However, since 2014, hostility toward America has become a mainstream mood and only in the last couple of years has the share of respondents with a positive attitude reached 40%-45%. In other words, anti-Americanism has become routine. Perhaps that is one reason the current standoff with the West now stirs less emotion than it might otherwise.

As in 2008 and 2014, the current conflict is primarily perceived by ordinary Russians as one imposed on Russia by the West. (Russian attitudes toward the EU track very closely with those toward the U.S., while positive views of China—which has largely sided with Russia throughout the Russo-Ukrainian conflict—recently hit a record high of 88%.) As a result, Russian public opinion has once again rallied around the authorities, as it did in 2008 and especially in 2014: Support for state institutions and government decisions has grown stronger.

These supportive attitudes, however, had long been low-stakes—based largely on the inaction and passivity of broad sectors of society. The average Russian leaves important political decisions at the mercy of the authorities, so long as they do not require direct participation from the individual. This partly explains why Russian authorities remained reluctant to start military mobilization for so long, wary of imposing higher costs on ordinary people.

Perhaps this is another reason that anti-Americanism has not gone off the charts: America is unloved, censured, suspected of malicious intent, but few Russians are interested in further escalation. Our surveys show that even amid the initial stage of the conflict with Ukraine eight years ago more than 60% of Russians favored better relations with the U.S. and other Western countries. Yet since many see the U.S. as the villain and blame it for the escalation in tensions, the majority believed it was the U.S., not Russia, that should have taken steps for de-escalation. In focus groups people usually say about the U.S.: “We would like a better relationship with them, but they don’t want it.” Regarding the current standoff, the mood of the majority can be described as “May this be over as soon as possible.”

Different Ages, Different News Sources

Anti-Americanism has long been more prevalent among older Russians, whose mistrust toward the U.S. is inherited from Soviet times. These negative feelings are stoked by state television, which often traffics in anti-Americanism and, for older Russians, remains the main source of information. Furthermore, older generations depend more on the state for their well-being than do younger people, and so tend to support the government’s decisions more eagerly than any other age group.

Younger Russians, on the contrary, are much friendlier toward America and the West in general. They are less influenced by old Soviet clichés, and many of them are great consumers of Western mass culture. In addition, young Russians tend not to get their news from TV, preferring online sources, which are much freer and more varied.

After the decline of positive attitudes toward the U.S. eight years ago, it was among young Russians that they first began to bounce back. And in recent years, up to the beginning of the current conflict, a positive attitude toward America prevailed among younger, more “modern” Russians. Even today, people under 25 see the U.S. in a more positive light than older Russians, more so even than eight years ago: In July 2014, 22% of younger Russians held positive views of the U.S.; in August 2022 the number was 35%.

This likely stems from young Russians’ widespread use of the internet, where independent media and liberal video bloggers—traditionally more pro-Western than state-run television—have mushroomed in recent years. These trends have coincided with the explosive growth of YouTube’s Russian-speaking audience: Between 2018 and 2022 the platform’s audience tripled and now amounts to one-third of the population, consisting primarily of people under 40. Telegram, created in 2013, has also become an important platform for the free exchange of opinions, now attracting up to 15% of the Russian population, primarily politically engaged and information-hungry people.

Independent journalists, activists and politicians have been able to take advantage of this shift. It is no coincidence that many popular Russian “vlogs” sprang up only two or three years ago. For the first time in many years, state television in Russia has independent competitors whose audiences are primarily young. The expansion of this new segment of the Russian internet may contribute to better attitudes toward the U.S. among its audiences, despite the ongoing conflict.

Not the Worst of It?

So there are several possible factors helping to keep anti-Americanism lower than one might expect: Routine—in this case, the habit of blaming the U.S. for Russia’s troubles—kills passion; fears of war temper criticism; and some subgroups in Russian society hold more positive views of the U.S. than the country as a whole, in particular younger Russians and people who get their news online (although negative attitudes prevail here as well). Ordinary Russians also tend to differentiate between the U.S. government and ordinary Americans, holding much more positive views of the latter.

However, it is important to remember that during the previous escalation anti-American sentiment in Russia did not reach its peak immediately, but almost a year after the conflict began—in late January 2015. (Comparing the trends then and now is convenient, since the Russian-Ukrainian conflicts of both 2014 and 2022 began in late February.) Only after the second Minsk agreement was signed in February 2015 and the relative normalization of the situation in the Donbas did public hostility toward America begin to slowly decrease as tensions deescalated. So, it is quite possible that we have yet to see new peaks of anti-Americanism, especially as the conflict seems to expand further.

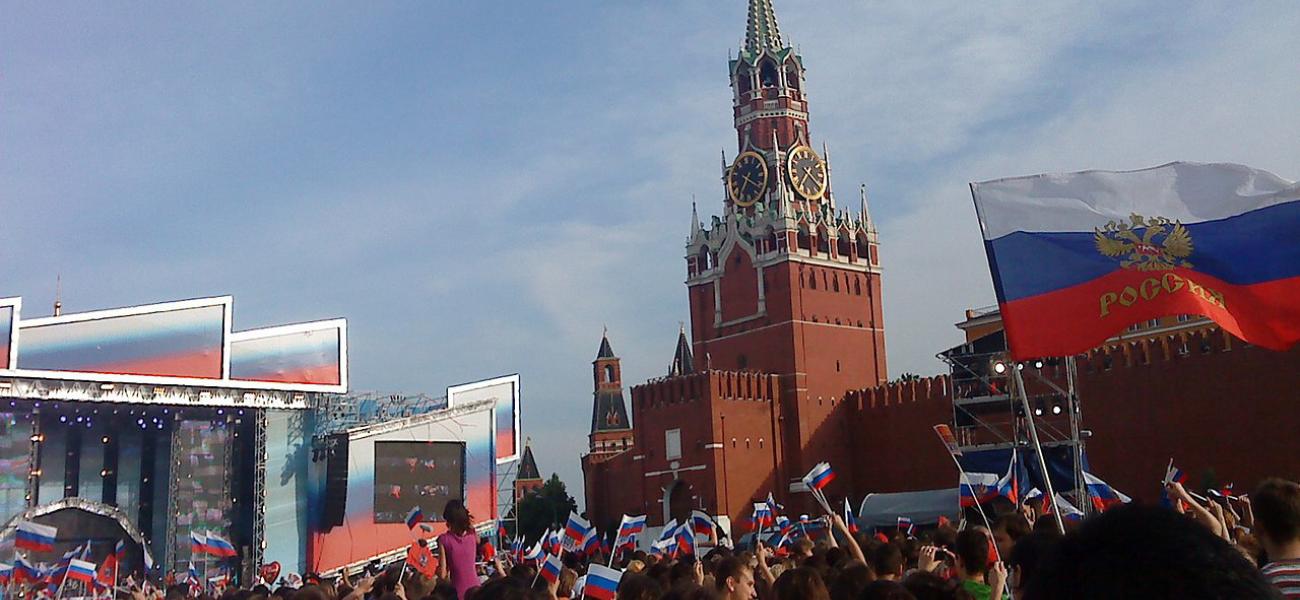

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. Photo by Dmitry Dzhus shared under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment