GREENWASHING

How the 2022 World Cup rebuilt a market for dodgy carbon creditsBloomberg News | November 17, 2022

World Cup organizers have pledged to erase the event’s negative environmental impact. Credit: Adobe Stock

For almost a decade, the small, gas-rich country of Qatar has been one giant construction site. In preparation to host the FIFA World Cup this November, it’s built seven stadiums, new roads and dozens of hotels. Between the emissions generated by the new construction plus air travel to transport players and fans, the 2022 tournament is shaping up to be the most carbon-intensive on record.

World Cup organizers have pledged to erase the event’s negative environmental impact. They plan to make the event “carbon neutral” by buying offsets — paying, in theory, for carbon to be removed or reduced from the Earth’s atmosphere somewhere else.

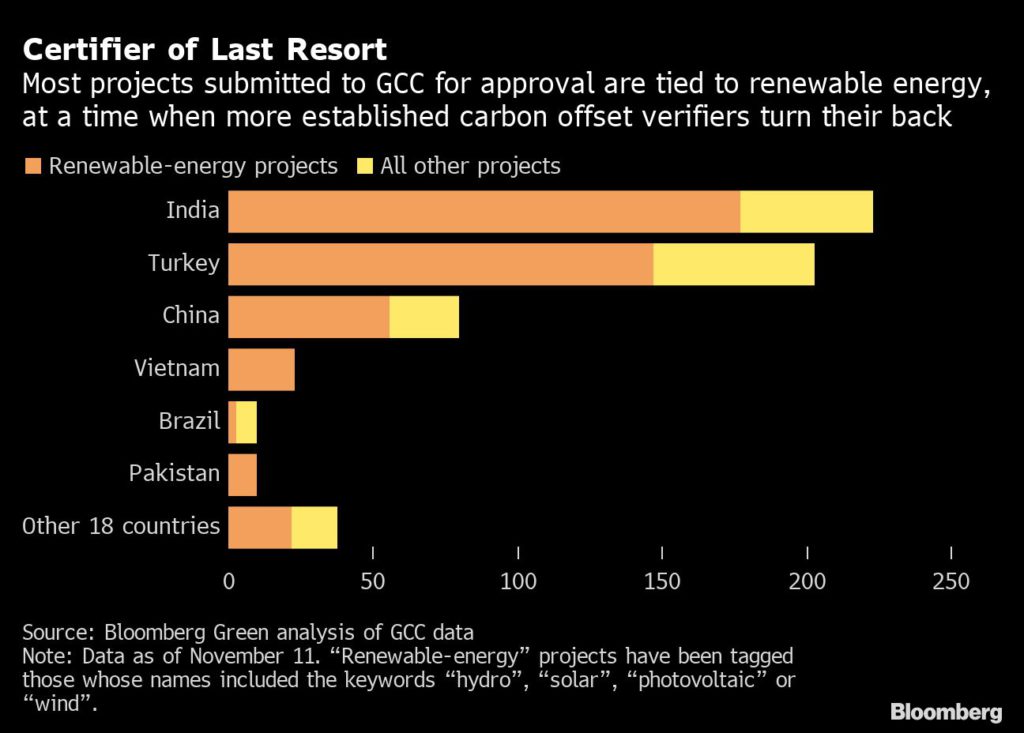

In practice, the plan is deeply flawed. Qatar and FIFA not only aren’t mitigating the environmental impact of the event, they may be inadvertently magnifying it. Specifically, they’ve said they want to buy some 1.8 million offsets from the Doha-based Global Carbon Council, bolstering a new, local organization that signs off on the kinds of projects that fail to meet minimum standards anywhere else in the world.

GCC is certifying credits that “will make no difference whatsoever to global emissions,” said Gilles Dufrasne, a policy lead at the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch and an expert advisor to the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market. “What GCC is offering here is at best ignorant, and at worst an obvious attempt to create more supply of low quality, low cost credits with an illusion of credibility.”

The problem, Dufrasne says, is that the projects that GCC approves can be tied to renewable energy developments in middle-income countries like India, Turkey and Serbia. In the past, a solar, wind or hydroelectric plant could generate carbon credits on the basis that the additional revenue motivated developers to take steps to replace fossil fuel energy. Without the credits, the renewable energy projects wouldn’t get built.

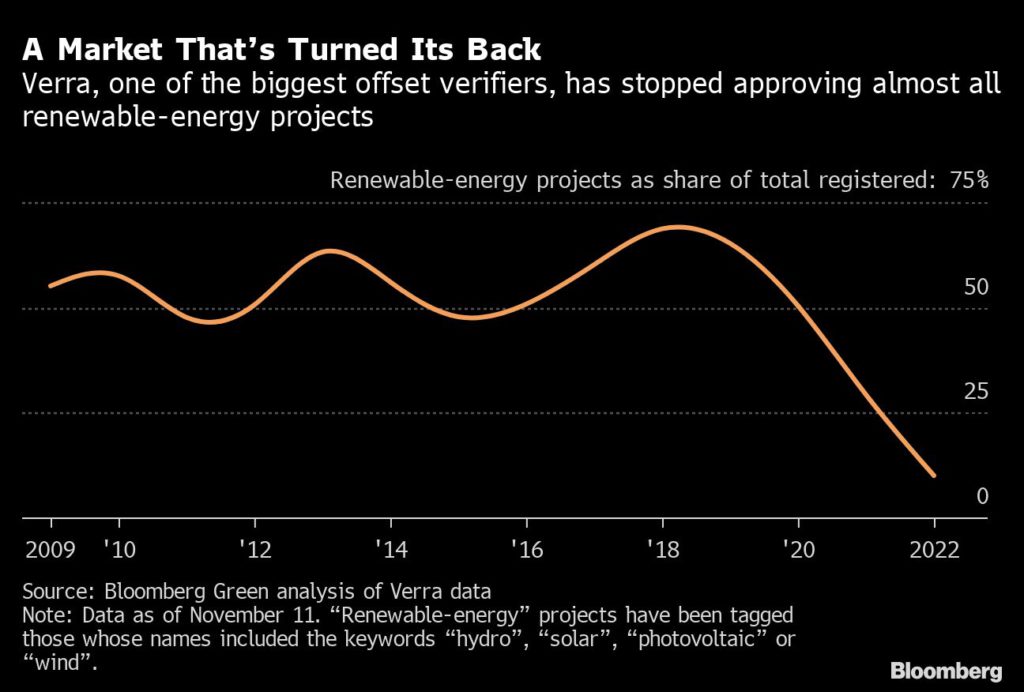

That’s no longer the case in most countries. From 2010 to 2021, the cost of renewable power fell by almost 90%. Solar and wind power are in high demand. Where developers don’t need an added incentive to build them, they shouldn’t generate credits that grant others license to pump new emissions into the atmosphere through, say, massive construction projects or air travel.

With a few, limited exceptions, Dufrasne says, “issuing carbon credits to large renewable energy projects in 2022 goes against fundamental integrity rules of carbon markets.”

That’s why Verra and Gold Standard, the world’s two biggest certifiers of carbon offset projects, have refused grid-connected renewable energy projects in all but the poorest countries since 2019. “ We came to the conclusion that only those in least-developed countries were still additional,” said David Antonioli, chief executive at Verra. The verification body introduced the ban to “make sure carbon finance was driven to where it is needed most,” he said.

The Science Based Targets initiative goes further, saying that companies should only buy offsets from projects that actively remove carbon from the atmosphere — a definition that excludes renewable energy projects.

GCC, though, strongly disagrees. Chief Operating Officer Kishor Rajhansa says it assesses each project individually, and renewable energy can be a legitimate source of offsets. “Renewable energy is the single biggest climate mitigation activity to reach a net-zero world,” he said.

“We disagree on principle with the decision taken by Verra and Gold Standard to make a blanket decision on all the projects from the developed world,” Rajhansa said. “We want to give every project owner a chance to demonstrate additionality.”

Operational since 2019, GCC had until recently certified just a few projects. But the publicity from the World Cup — along with a tightening of standards elsewhere — has lifted its business prospects significantly. The commitment from FIFA and the Supreme Committee to host a carbon neutral tournament and their ambition to source credits from the region gave the GCC plan impetus, Rajhansa said.

Now there are almost 600 projects waiting for GCC approval, submitted by project developers or middlemen with nowhere else to turn. Indian energy company Emergent Ventures has submitted a handful of grid-connected solar projects to GCC for certification. “It’s the only working standard allowing registration of renewable energy power projects,” Emergent Ventures director Atul Sanghal said. “This is the main reason to go for GCC registration.”

GCC may generate up to 400 million credits over the next decade, said Rajhansa. At today’s prices, that would be worth around $1 billion. Almost all are renewable energy projects and rely either on GCC’s own methodology or that produced by the United Nations Clean Development Mechanism, a scheme established in 1997 by the Kyoto Protocol that’s now considered outdated and is “de facto dead,” according to Dufrasne.

Carbon offsets can be bought and sold with little oversight. The United Nations and other global bodies are working on universal standards, and regulators are increasingly interested in the exchanges that have cropped up to connect buyers and sellers.

So far, the World Cup organizers have been the sole purchasers of credits verified by GCC, which charges to verify offset projects and is owned by the Qatari government. However, all approved and submitted projects are marked by GCC as “CORSIA eligible,” meaning they could be used by airlines to meet their offsetting obligations under the scheme going by the same name.

In response to questions this month, FIFA said all of the event organizers — FIFA, the Supreme Committee and its Qatar 2022 committee — will decide independently whether and where to buy offsets. FIFA now says it will not be purchasing offsets verified by GCC.

The Supreme Committee said it supported the formation of the GCC in 2016 to contribute to regional climate action, but GCC is now operating as an independent organization. “Sustainability has defined all our planning and operations,” the Committee added, which include a new solar power plant, tree nursery, green spaces and electric buses.

The emergence of GCC has spurred new calls for global regulation of the voluntary carbon market, establishing a common, high standard for the credits that can be credibly claimed to offset emissions. Even if GCC tightened its standards in line with other bodies, there’s nothing to stop another organization from popping up to verify renewable energy credits, and as long as the offsets are “verified,” companies will buy them and apply them to net zero goals.

“Without much stricter rules and oversight, the [market] will not play a significant role in reaching the Paris Agreement goals; on the contrary, it could end up facilitating more emissions,” said Juerg Fuessler, managing partner at INFRAS, a sustainability consultancy, and former member of a UN expert panel on carbon crediting methodologies.

Buyers of poor quality credits “divert resources and attention from necessary real and additional mitigation activities,” Fuessler said, and fail to move the needle on meaningful emissions reductions.

(By Natasha White and Verity Ratcliffe, with assistance from Demetrios Pogkas)

No comments:

Post a Comment