Brazen effort to bring sanity to cross-continental rail travel governs many aspects of life today

By Kerry J. Byrne | Fox News

American and Canadian railroads enacted time zones — a concept that schedules all aspects of life today — on this day in history, Nov. 18, 1883.

The rail industry's creation of time zones was a brazen attempt to bend time to its will.

It brought sanity to a sprawling patchwork system of local timekeeping based on the ancient method of following the sun, the system used since human time began.

"Back in the early 1800s, the sun served as the official ‘clock’ in the U.S., and time was based on each city’s own solar noon, or the point when the sun is highest in the sky," Union Pacific railroad writes in its history of time zones.

"This timekeeping method resulted in the creation of more than 300 local time zones across the country — not to mention disparity in local time depending on your location. So, for example, while it could be 12:09 p.m. in New York, it could also be 12:17 p.m. in Chicago."

Union Pacific Diesel Locomotive Train, Cajon Pass near Ono, California, 1964. Sprawling distances across North America and a patchwork of local methods of timekeeping encouraged railroads to adopt time zones in 1883. (Photo by: GHI/Universal History Archive via Getty Images)

The system that railroads pioneered did not become federal law until the passage of the Standard Time Act on March 19, 1918, amid World War I.

With an estimated 100,000 Americans alive today over the age of 100, tens of thousands of U.S. citizens still alive now were born into a world without uniform time.

"Back in the early 1800s, the sun served as the official ‘clock’ in the U.S." — Union Pacific railroad

Charles F. Dowd, an educator at what's now Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, first proposed the concept of time zones across the U.S. in 1870.

"Dowd’s plan divided the country into four time zones. He used the 75th meridian, which runs through New York State, as the base for his Eastern Standard Time," explains the Madison Historical Society from the Connecticut hometown of the time pioneer.

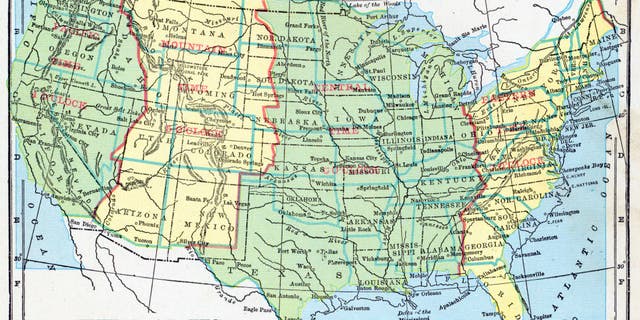

A color map showing the divisions of standard time, Pacific, Mountain, Central and Eastern, across the United States, 1922. (Photo by Interim Archives/Getty Images)

"He then assigned three cross-country meridians: Central Standard (90th); Mountain Standard (105th); Pacific Standard (120th). Each zone time was set one hour apart."

Dowd slowly built support for his plan from academics. But the fractured railroad industry, with hundreds of companies competing for traffic and dollars, proved harder to harness.

He found an influential ally in William F. Allen, a railroad engineer and editor of the "Traveler's Official Railway Guide."

"With his helpful modifications — and Dowd’s continual work — Allen convinced railroad officials to adopt (time zones)," the Madison Historical Society explains.

Grand Central Terminal in midtown Manhattan opened in 1913 just 30 years after railroads pioneered the creation of time zones — and five years before the system became federal law in the United States. (Kerry J. Byrne/Fox News Digital)

"On November 18, 1883, Allen was on hand at the Western Union Telegraph System building in New York City to witness the plan’s implementation. Room 148 contained the company’s regulator clock. At 9 a.m., the clock was stopped for precisely three minutes and 58:38 seconds. The clock was then restarted, and Eastern Standard Time was born."

The concept of time zones quickly spread around the world.

"The following year a conference was held in New York City to determine the location of the prime meridian, which refers to zero degrees longitude," reports the website of California cartographer GeoJango Maps.

"It was decided that Greenwich, England, would act as the Earth's prime meridian and that the 24 time zones would be based off … this location."

The four continental North American time zones used today — Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific — look substantially similar to those envisioned by Dowd in the 1870s.

In this November 1943 file photo, bodies and wrecked amphibious tractors litter a battlefield after U.S. Marines from the 2nd Division forced back the Japanese on Betio island in the Tarawa Atoll, Kiribati. The nation of Kiribati sprawls across both the International Date Line and the equator. (AP Photo, File)

The time zone concept, as clean as it may appear, creates chaos in one isolated Pacific Ocean island nation.

Kiribati sprawls across about 1.4 million square miles of ocean. The World War II Battle of Tarawa, pitting United States Marines against entrenched Japanese defenders, took place in what's now Kiribati.

The nation straddles both the International Date Line and the equator. So it can be Friday and Saturday in Kiribati — and both summer and winter — all at the same time.

The nation created its own unilateral time zones, bucking the international standard, on Dec. 31, 1994, to solve the problem.

"These rarest of time zones were established by Kiribati," writes watchmaker TAG Heuer, "for the purpose of removing certain absurdities from the daily lives of its citizens."

"Today, the U.S Department of Transportation oversees the nation’s time zones and the uniform observance of Daylight Saving Time," writes Union Pacific, "including exercising the authority that allows a state to change its official time zone."

Kerry J. Byrne is a lifestyle reporter with Fox News Digital.

No comments:

Post a Comment