The Conversation

November 15, 2022

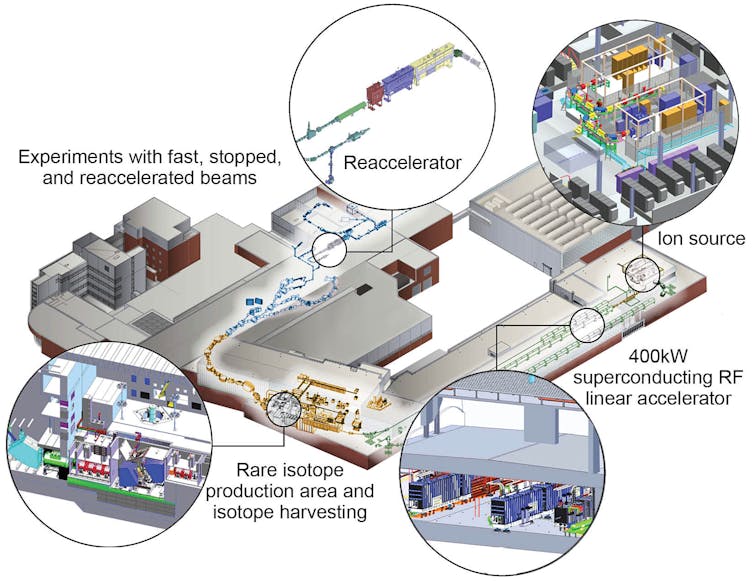

A new particle accelerator at Michigan State University is set to discover thousands of never-before-seen isotopes. Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, CC BY-ND

Just a few hundred feet from where we are sitting is a large metal chamber devoid of air and draped with the wires needed to control the instruments inside. A beam of particles passes through the interior of the chamber silently at around half the speed of light until it smashes into a solid piece of material, resulting in a burst of rare isotopes.

This is all taking place in the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, or FRIB, which is operated by Michigan State University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Starting in May 2022, national and international teams of scientists converged at Michigan State University and began running scientific experiments at FRIB with the goal of creating, isolating and studying new isotopes. The experiments promised to provide new insights into the fundamental nature of the universe.

We are two professors in nuclear chemistry and nuclear physics who study rare isotopes. Isotopes are, in a sense, different flavors of an element with the same number of protons in their nucleus but different numbers of neutrons.

The accelerator at FRIB started working at low power, but when it finishes ramping up to full strength, it will be the most powerful heavy-ion accelerator on Earth. By accelerating heavy ions – electrically charged atoms of elements – FRIB will allow scientists like us to create and study thousands of never-before-seen isotopes. A community of roughly 1,600 nuclear scientists from all over the world has been waiting for a decade to begin doing science enabled by the new particle accelerator.

The first experiments at FRIB were completed over the summer of 2022. Even though the facility is currently running at only a fraction of its full power, multiple scientific collaborations working at FRIB have already produced and detected about 100 rare isotopes. These early results are helping researchers learn about some of the rarest physics in the universe.

Rare isotopes are radioactive and decay over time as they emit radiation – visible here as the streaks coming from the small piece of uranium in the center.

What is a rare isotope?

It takes incredibly high amounts of energy to produce most isotopes. In nature, heavy rare isotopes are produced during the cataclysmic deaths of massive stars called supernovas or during the merging of two neutron stars.

To the naked eye, two isotopes of any element look and behave the same way – all isotopes of the element mercury would look just like the liquid metal used in old thermometers. However, because the nuclei of isotopes of the same element have different numbers of neutrons, they differ in how long they live, what type of radioactivity they emit and in many other ways.

For example, some isotopes are stable and do not decay or emit radiation, so they are common in the universe. Other isotopes of the very same element can be radioactive so they inevitably decay away as they turn into other elements. Since radioactive isotopes disappear over time, they are relatively rarer.

Not all decay happens at the same rate though. Some radioactive elements – like potassium-40 – emit particles through decay at such a low rate that a small amount of the isotope can last for billions of years. Other, more highly radioactive isotopes like magnesium-38 exist for only a fraction of a second before decaying away into other elements. Short-lived isotopes, by definition, do not survive long and are rare in the universe. So if you want to study them, you have to make them yourself.

The Facility for Rare Isotope Beams was designed to allow researchers to create rare isotopes and measure them before they decay.

Creating isotopes in a lab

While only about 250 isotopes naturally occur on Earth, theoretical models predict that about 7,000 isotopes should exist in nature. Scientists have used particle accelerators to produce around 3,000 of these rare isotopes.

The green-colored chambers use electromagnetic waves to accelerate charged ions to nearly half the speed of light.

Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, CC BY-ND

The FRIB accelerator is 1,600 feet long and made of three segments folded in roughly the shape of a paperclip. Within these segments are numerous, extremely cold vacuum chambers that alternatively pull and push the ions using powerful electromagnetic pulses. FRIB can accelerate any naturally occurring isotope – whether it is as light as oxygen or as heavy as uranium – to approximately half the speed of light.

To create radioactive isotopes, you only need to smash this beam of ions into a solid target like a piece of beryllium metal or a rotating disk of carbon.

There are many different instruments designed to measure specific attributes of the particles created during experiments at FRIB – like this instrument called FDSi, which is built to measure charged particles, neutrons and photons.

Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, CC BY-ND

The impact of the ion beam on the fragmentation target breaks the nucleus of the stable isotope apart and produces many hundreds of rare isotopes simultaneously. To isolate the interesting or new isotopes from the rest, a separator sits between the target and the sensors. Particles with the right momentum and electrical charge will be passed through the separator while the rest are absorbed. Only a subset of the desired isotopes will reach the many instruments built to observe the nature of the particles.

The probability of creating any specific isotope during a single collision can be very small. The odds of creating some of the rarer exotic isotopes can be on the order of 1 in a quadrillion – roughly the same odds as winning back-to-back Mega Millions jackpots. But the powerful beams of ions used by FRIB contain so many ions and produce so many collisions in a single experiment that the team can reasonably expect to find even the rarest of isotopes. According to calculations, FRIB’s accelerator should be able to produce approximately 80% of all theorized isotopes.

While only about 250 isotopes naturally occur on Earth, theoretical models predict that about 7,000 isotopes should exist in nature. Scientists have used particle accelerators to produce around 3,000 of these rare isotopes.

The green-colored chambers use electromagnetic waves to accelerate charged ions to nearly half the speed of light.

Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, CC BY-ND

The FRIB accelerator is 1,600 feet long and made of three segments folded in roughly the shape of a paperclip. Within these segments are numerous, extremely cold vacuum chambers that alternatively pull and push the ions using powerful electromagnetic pulses. FRIB can accelerate any naturally occurring isotope – whether it is as light as oxygen or as heavy as uranium – to approximately half the speed of light.

To create radioactive isotopes, you only need to smash this beam of ions into a solid target like a piece of beryllium metal or a rotating disk of carbon.

There are many different instruments designed to measure specific attributes of the particles created during experiments at FRIB – like this instrument called FDSi, which is built to measure charged particles, neutrons and photons.

Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, CC BY-ND

The impact of the ion beam on the fragmentation target breaks the nucleus of the stable isotope apart and produces many hundreds of rare isotopes simultaneously. To isolate the interesting or new isotopes from the rest, a separator sits between the target and the sensors. Particles with the right momentum and electrical charge will be passed through the separator while the rest are absorbed. Only a subset of the desired isotopes will reach the many instruments built to observe the nature of the particles.

The probability of creating any specific isotope during a single collision can be very small. The odds of creating some of the rarer exotic isotopes can be on the order of 1 in a quadrillion – roughly the same odds as winning back-to-back Mega Millions jackpots. But the powerful beams of ions used by FRIB contain so many ions and produce so many collisions in a single experiment that the team can reasonably expect to find even the rarest of isotopes. According to calculations, FRIB’s accelerator should be able to produce approximately 80% of all theorized isotopes.

The first two FRIB scientific experiments

A multi-institution team led by researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK), Mississippi State University and Florida State University, together with researchers at MSU, began running the first experiment at FRIB on May 9, 2022. The group directed a beam of calcium-48 – a calcium nucleus with 48 neutrons instead of the usual 20 – into a beryllium target at 1 kW of power. Even at one quarter of a percent of the facility’s 400-kW maximum power, approximately 40 different isotopes passed through the separator to the instruments.

The FDSi device recorded the time each ion arrived, what isotope it was and when it decayed away. Using this information, the collaboration deduced the half-lives of the isotopes; the team has already reported on five previously unknown half-lives.

The second FRIB experiment began on June 15, 2022, led by a collaboration of researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, ORNL, UTK and MSU. The facility accelerated a beam of selenium-82 and used it to produce rare isotopes of the elements scandium, calcium and potassium. These isotopes are commonly found in neutron stars, and the goal of the experiment was to better understand what type of radioactivity these isotopes emit as they decay. Understanding this process could shed light on how neutron stars lose energy.

The first two FRIB experiments were just the tip of the iceberg of this new facility’s capabilities. Over the coming years, FRIB is set to explore four big questions in nuclear physics: First, what are the properties of atomic nuclei with a large difference between the numbers of protons and neutrons? Second, how are elements formed in the cosmos? Third, do physicists understand the fundamental symmetries of the universe, like why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe? Finally, how can the information from rare isotopes be applied in medicine, industry and national security?

Sean Liddick, Associate Professor of Chemistry, Michigan State University and Artemis Spyrou, Professor of Nuclear Physics, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment