Protest has a woman's face. How Iran's unrest is pushing the regime for real reforms

Nikolai Kozhanov

24 октября 2022

Protests have erupted with renewed vigor in Iran after a 16-year-old Iranian woman, Asra Panahi, died on October 13 after being beaten by security forces for refusing to sing a song praising the country's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. These are the first protests to last this long, have such a wide geographic scope, and draw from such a significant social base, but the main difference is the protesters' demands. Moving away from mere economic grievances, they want serious political change, including the dismantling of the regime. The protests have also stirred up the national suburbs - Iranian Kurdistan (Mahsa Amini, who died after being detained by security forces was of Kurdish descent), Azerbaijan and Baluchistan, forcing the protesters to raise a national issue that is also sensitive to Tehran, and the Iranian authorities to send troops against Kurdish movements both in their own territory and in the lands of neighboring Iraq. The spontaneity of the protest, the lack of a coordinated leadership and the absence of clearly defined goals do not yet allow us to consider it the beginning of a revolution. But even if the Iranian authorities manage to survive the current crisis, it will be difficult for them to regain people's trust, and a major reform of the country is already inevitable.

A New President and a Weak Economy

Iran's economic problems have created an atmosphere and a general backdrop that further encourage and fuel the protesters’ anger. In 2022, the inflation rate exceeded 50%. The lower strata of Iranian society were the most susceptible to its negative effects. Prices continued to rise while the purchasing power of households fell, and GDP growth slowed. Thanks to high oil prices, the Iranian economy has not shown negative growth rates in 2021-2022. At the same time, the government did not do enough to solve the economic problems of the population.

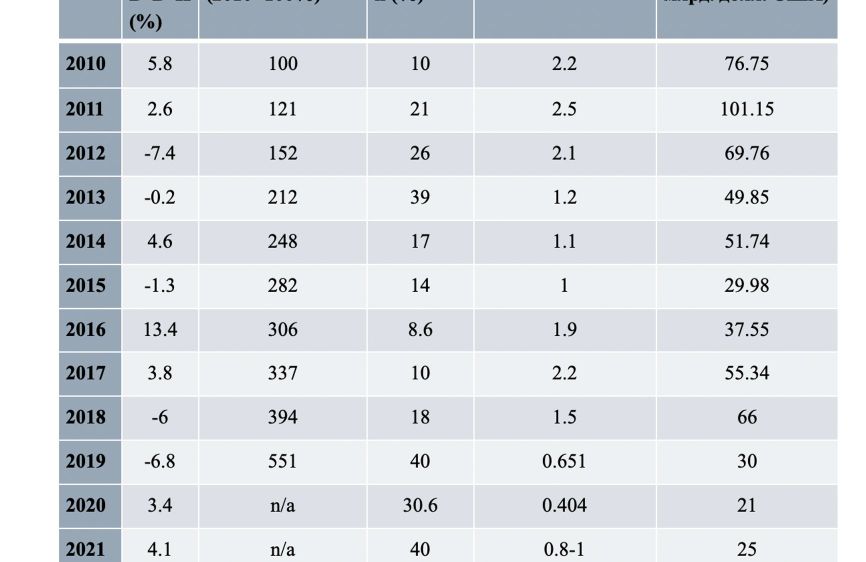

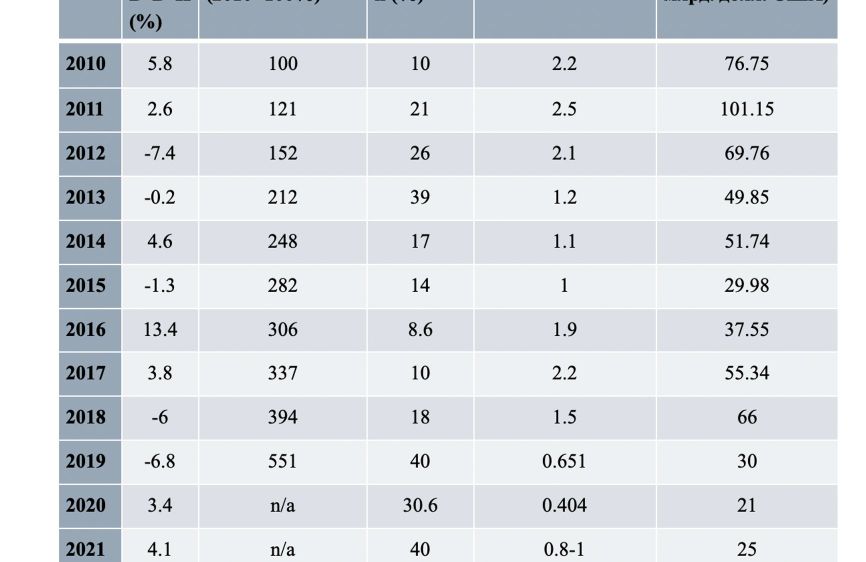

Table 1: Iran's economic performance indicators in 2010-2023 Sources: World Bank, Central Bank of Iran, Parliament of Iran. The 2022 and 2023 data and the 2021-2023 oil indicators are estimated

In 2021 and early 2022, President-elect Ebrahim Raisi's actions in the economic sphere were leisurely and inert. This was largely due to the fact that the new ruler did not have much experience in managing the economy - he had built his career in the judiciary. Raisi's entire managerial career was limited to three years (2016-2019), which he spent at the head of a major religious foundation, Astan-e Quds Razavi. Judging by his statements, he tried to avoid innovation, focusing on the experience of his predecessors. In practice, this meant further implementation of the “resistance economy” model based on the principle of partial self-sufficiency. Raisi's economic program was built on populist statements: he was rightly concerned about unemployment, corruption, environmental problems. However, he had no clear action plan or new ideas for real solutions to the problems.

Raisi failed to assemble a strong economic team of like-minded people in his government. In the mid-summer of 2022, the Iranian press reported on a dispute between Vice President for Economic Affairs Mohsen Rezaei and Minister of Economy Ehsan Khandouzi over the interbank interest rate. The Ministry of Economy asked the Central Bank to lower the interbank interest rate, while the Vice President for Economic Affairs insisted that the interest rate should not be lowered because of high inflation. Such a dispute was far from the only one within the economic bloc. As a result, the ongoing contradictions within the team delayed the implementation of the necessary measures.

Protests in Iran twitter.com/AnisaEftekhari

The difficult situation in the global oil and gas markets and the election of U.S. President Joe Biden in early 2021 did not help the Iranian economy either. Unlike his predecessor Donald Trump, Biden has not been as tough on enforcing the oil embargo imposed on Iran. At the same time, Tehran itself had already developed a scheme to circumvent the sanctions by bringing some of its oil to the world market. Rising oil prices and the fact that exports ensured an almost positive trade balance allowed Iran to generate additional revenues, which it was actively spending to maintain the political regime (see Table 1). This provided an opportunity for Raisi to reconsider his approaches to resolving the issue of the Iranian nuclear program. Despite initial expectations that Tehran would try to conclude a new agreement with international negotiators as soon as possible in order to relieve the sanctions pressure, it did not happen. On the contrary, the president's team chose a strategy of protracted negotiations.

Unlike Trump, Biden has not been as tough on enforcing the oil embargo imposed on Iran

At least a partial easing of sanctions pressure would have moved the Iranian resistance economy from survival to partial growth. This would not mean an immediate improvement of socio-economic indicators, but the lifting of sanctions would have had at least an indirect positive effect on them.

Protests have erupted with renewed vigor in Iran after a 16-year-old Iranian woman, Asra Panahi, died on October 13 after being beaten by security forces for refusing to sing a song praising the country's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. These are the first protests to last this long, have such a wide geographic scope, and draw from such a significant social base, but the main difference is the protesters' demands. Moving away from mere economic grievances, they want serious political change, including the dismantling of the regime. The protests have also stirred up the national suburbs - Iranian Kurdistan (Mahsa Amini, who died after being detained by security forces was of Kurdish descent), Azerbaijan and Baluchistan, forcing the protesters to raise a national issue that is also sensitive to Tehran, and the Iranian authorities to send troops against Kurdish movements both in their own territory and in the lands of neighboring Iraq. The spontaneity of the protest, the lack of a coordinated leadership and the absence of clearly defined goals do not yet allow us to consider it the beginning of a revolution. But even if the Iranian authorities manage to survive the current crisis, it will be difficult for them to regain people's trust, and a major reform of the country is already inevitable.

A New President and a Weak Economy

Iran's economic problems have created an atmosphere and a general backdrop that further encourage and fuel the protesters’ anger. In 2022, the inflation rate exceeded 50%. The lower strata of Iranian society were the most susceptible to its negative effects. Prices continued to rise while the purchasing power of households fell, and GDP growth slowed. Thanks to high oil prices, the Iranian economy has not shown negative growth rates in 2021-2022. At the same time, the government did not do enough to solve the economic problems of the population.

Table 1: Iran's economic performance indicators in 2010-2023 Sources: World Bank, Central Bank of Iran, Parliament of Iran. The 2022 and 2023 data and the 2021-2023 oil indicators are estimated

In 2021 and early 2022, President-elect Ebrahim Raisi's actions in the economic sphere were leisurely and inert. This was largely due to the fact that the new ruler did not have much experience in managing the economy - he had built his career in the judiciary. Raisi's entire managerial career was limited to three years (2016-2019), which he spent at the head of a major religious foundation, Astan-e Quds Razavi. Judging by his statements, he tried to avoid innovation, focusing on the experience of his predecessors. In practice, this meant further implementation of the “resistance economy” model based on the principle of partial self-sufficiency. Raisi's economic program was built on populist statements: he was rightly concerned about unemployment, corruption, environmental problems. However, he had no clear action plan or new ideas for real solutions to the problems.

Raisi failed to assemble a strong economic team of like-minded people in his government. In the mid-summer of 2022, the Iranian press reported on a dispute between Vice President for Economic Affairs Mohsen Rezaei and Minister of Economy Ehsan Khandouzi over the interbank interest rate. The Ministry of Economy asked the Central Bank to lower the interbank interest rate, while the Vice President for Economic Affairs insisted that the interest rate should not be lowered because of high inflation. Such a dispute was far from the only one within the economic bloc. As a result, the ongoing contradictions within the team delayed the implementation of the necessary measures.

Protests in Iran twitter.com/AnisaEftekhari

The difficult situation in the global oil and gas markets and the election of U.S. President Joe Biden in early 2021 did not help the Iranian economy either. Unlike his predecessor Donald Trump, Biden has not been as tough on enforcing the oil embargo imposed on Iran. At the same time, Tehran itself had already developed a scheme to circumvent the sanctions by bringing some of its oil to the world market. Rising oil prices and the fact that exports ensured an almost positive trade balance allowed Iran to generate additional revenues, which it was actively spending to maintain the political regime (see Table 1). This provided an opportunity for Raisi to reconsider his approaches to resolving the issue of the Iranian nuclear program. Despite initial expectations that Tehran would try to conclude a new agreement with international negotiators as soon as possible in order to relieve the sanctions pressure, it did not happen. On the contrary, the president's team chose a strategy of protracted negotiations.

Unlike Trump, Biden has not been as tough on enforcing the oil embargo imposed on Iran

At least a partial easing of sanctions pressure would have moved the Iranian resistance economy from survival to partial growth. This would not mean an immediate improvement of socio-economic indicators, but the lifting of sanctions would have had at least an indirect positive effect on them.

Change “from on high” did not work

By late spring 2022, Raisi put forward a plan for economic transformation that implied significant reform of the subsidy system. Iran abolished the subsidized exchange rate of the Iranian currency against the U.S. dollar, which had been used to buy and import essential goods. Targeted direct payments to the people were also attempted. Iran's population was divided into ten income groups, from the poorest to the richest. The first three low-income categories received a monthly amount of 4 million Iranian rials ($13.5 at the free market exchange rate), while middle-income Iranians in categories 4-9 received 3 million Iranian rials ($10.1). Those in the richest, 10th income group received no payments. Raisi said the money would be paid over two summer months before being replaced by an “e-coupon” system.

The economic reform plan was full of critical flaws, which served as another catalyst for the protests. The abolition of the special dollar exchange rate helped eliminate one source of corruption and embezzlement, but inevitably pushed up consumer prices of imported goods. The decision to restructure the payment of direct subsidies eased the burden on the budget in the long run, but accelerated the growth of inflation. No alternative mechanisms to curb inflation were proposed. On the contrary, the government steadily reduced the annual volume of issued bonds in the absence of demand, while private investment in the Iranian economy shrank under the pressure of public distrust of the government's economic policies. In different circumstances, both factors could have helped absorb the excess liquidity.

Protest in Tehran

The banking sector, too, has found itself in a difficult situation. According to Iranian economists, high inflation and declining revenues have been spurring small businesses' need for more credit. The banks, on the contrary, are either denying financial support to businesses in these conditions, or setting maximum interest rates.

In addition, the very model of “resistance economy” chosen by the Iranian leadership, without amendments, is unsustainable in the long run. Its application was able to stabilize Iran after the initial shock of the sanctions imposed in 2010-12 and 2018. However, this model has failed to solve the problem of their negative impact on the very foundations of the Iranian economy. The sanctions have hit the Iranian economy's ability to effectively develop its production base, attract foreign investment, use long-term foreign bank loans, and enter new markets.

The deterioration of Iran's production base will inevitably become a major obstacle to the country's economic development and stable budget revenues. U.S. sanctions have been one of the main reasons for the slowdown in Iran's oil and gas sector. Since 2017, there has been no direct foreign investment in any of the country’s major hydrocarbon projects, which means that no new foreign technology has entered the oil sector. Moreover, sanctions have partially stalled the development of Iran's natural gas sector, leaving the country, with its vast natural gas resources, a small player in the international market.

Since 2017, there has been no direct foreign investment in any of Iran’s major hydrocarbon projects

The food and textile sectors also reduced production in 2019-2022. It affected the country's foreign trade: Iranian exports have been declining in both value and weight terms, while the trade balance (excluding oil and gas) has been steadily trending negative.

Social background

The inability of Iran's leadership to convert slow economic growth into social development is another long-term structural problem. Since the mid-2010s, the purchasing power and incomes of Iranian households have been steadily declining. Moreover, basic needs expenses have shrunk in favor of housing payments (Table 2). By 2022, 60 percent of the Iranian population was either slightly above or just below the poverty line. Meanwhile, 18.4% lived in absolute poverty.

Young women are the face of the current protests, as they represent two of the most vulnerable groups in Iranian society: women and youth.

Protest in Tehran after the death of Mahsa Amini twitter

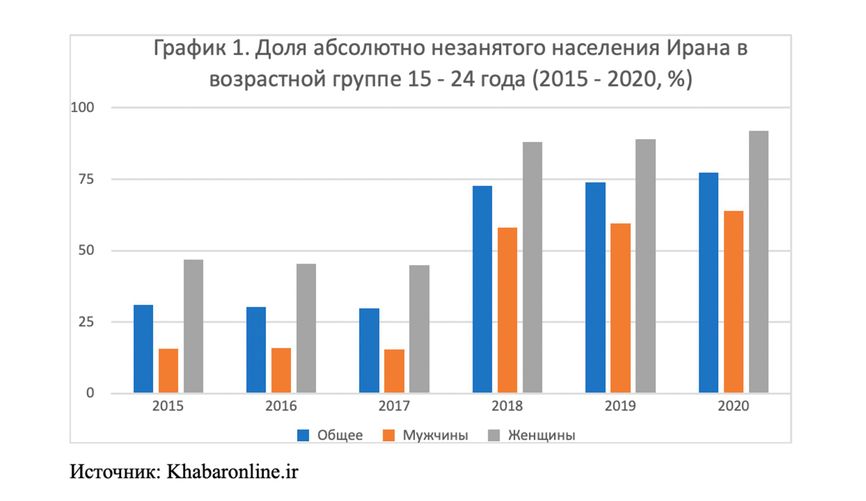

Iranian economists estimate that the unemployment rate among women is 13%, and half as much among men (7.2%). These figures are twice as high among young people between the ages of 18 and 35. According to other data, 77% (7.1 million people) of 15 to 24-year-olds are unemployed (diagram 1). There are also gender inequalities in employment. For example, only one in five women participates in the economy.

Loss of faith and violation of tacit agreements

Economic and social problems in Iran have set the stage for the current protests, political reasons serving as a catalyst: the Iranian people are losing faith in the very idea of the Islamic Republic. The historically low turnout in the de facto organized presidential election of 2021 and the number of invalid ballots exceeding the number of votes cast for the other candidates were the first warning signal for the Iranian political system.

Protests in Iran twitter.com/AJEnglish

People reacted negatively to the government's idea of mopping up the electoral landscape to ensure Raisi's victory. His failed socio-economic policies only made matters worse, destroying hope even among those who still believed in the ability of the conservative camp to rectify the situation. Meanwhile, the failure of Raisi's predecessors from other movements to make improvements has raised the legitimate question of whether there are forces within the current political system capable of ensuring development and prosperity.

The conservatives have become hostage to their own slogans that after the 2021 presidential election, they were able to achieve unity between the Supreme Leader of Iran, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and all branches of the government. Now the government cannot use Iran's traditional political maneuvering, in which the president acted as a scapegoat whom Khamenei could blame for all the troubles and from whom he could demonstratively distance himself. Today, Raisi and Khamenei are perceived as a solid tandem. Which means that any attack on the president automatically means an attack on the Supreme Leader.

Today, Raisi and Khamenei are perceived as a strong tandem. Which means that any attack on the president automatically means an attack on the Supreme Leader

The final straw was Raisi's decision to deprive the Iranian population of the freedom for women not to wear a headscarf and to have “sinful pleasures” such as participating in noisy house parties, going to music nights in restaurants and consuming alcohol and drugs (both of which are officially forbidden in Iran). This was part of a tacit agreement between the people and the government: the population endured economic hardship but remained loyal in exchange for the right to ignore certain rules. Under the conservative Raisi, however, this arrangement, which served as a kind of safety valve, was broken, and with it the people's patience waned.

So far, the intensity of the protests suggests that Tehran will not be able to simply suppress them. Sooner or later, the Iranian political system will have to change. Moreover, the depth of the current discontent in Iranian society will not allow the political system to get by with minor transformations and reforms in the economic or political sphere alone.

Young women protesting in Karaj, near Tehran on Nov. 3, 2022

Author: Iran International Newsroom

Iran Politics Iran Protests

A think tank close to Iran's security council has concluded that protests over the years have become more serious and more frequent as grievances went unanswered.

The research conducted by the National Security Monitor magazine for its September-October 2022 issue, says the current uprising is pluralist, has major objectives to change the bigger picture in Iran, is cyberspace-based, and does not seem to be backed by any institution.

The magazine is believed to be close to the Islamic Republic's Supreme National Security Council.

The research further found that collective reactions to events relating to the protests spread quickly although there seems to be no formal organization and leadership for the movement.

Other findings of the research include the fact that the uprising aims to bring about fundamental changes in Iran's political establishment, is backed by various layers of socio-political groups while also enjoying wholehearted support from the Iranian opposition abroad.

The government policy of suppressing protests by force and then failing to address the underlying problems has led to a worsening situation after each round of unrest and today, it might have become too late to come to peace with the disgruntled masses.

The study also found that although previously major protests occurred almost once in every decade [like the protests by the student movement in 1999 and the post-election unrest in 2009],during the past five or six years the interval between various protests have become shorter and they have occurred every one or two years. Soon, major protests may take place in Iran once in every two to three months, the study predicted.

Protesters in the central city of Arak torch a motorcycle used by security forces. Oct. 29, 2022

The conclusions corroborate the attestations of individual social scientists and political activists who have generally attributed the protest in Iran to promises that have not been met for a long time and demands that have been ignored by several governments during the past 40 years.

Meanwhile the study also observed that the driving force behind the current movement are youngsters born after the second half of the 1990s. This part of the findings also corroborate with what Iranian sociologists and political activists have said or written during the past two months.

The main problem of the new generation appears to be lack of social freedoms within an Islamic system and general hopelessness about the future.

As this study and several Iranian sociologists have observed, the disillusioned new generation of Iranians is fed up with senseless and inefficient bureaucracy and at the same time does not believe in the outdated and meaningless ideology the Islamic Republic has been propagating during the past four decades.

Generally, according to this research, the current movement in Iran is marked by a generation gap, fluctuating at times between activism and mutiny, not being mainly about economic demands, changing mood between anger and hope, using opportunities provided by events, and a horizontal steering structure [lack of formal leadership].

Meanwhile, according to the study the way the Iranian government has been handling the protests have not changed during the past four decade. It is common knowledge that the government's first and only solution to any crisis like the current uprising is handling it violently. At times, such as during the protests against rising fuel prices in 2019, Iranian government forces have killed hundreds to silence uprisings. But this way of handling crises, coupled with failure to address systemic problems is only a temporary solution and protests flare up as soon as another event triggers a new round of protests. What triggered the current wave of protests in Iran was the murder of a young woman in mid-September while she was in morality police custody.

Veils are burning and the regime is cracking down. What is the endgame for the protests in Iran?

From a brutal crackdown to civil war, an expert looks at scenarios for how a current wave of protests might unfold.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/LG7CAIFIXFA5JNSJKU6EJATMKI.jpg)

Iranian protesters march down a street in Tehran, Iran, on Oct. 1.

Contributor/Getty Images

Roxane Farmanfarmaian

Special Contributor

November 22, 2022

It’s been more than two months. There are daily protests against the regime in Iran in several parts of the country and daily reminders of the regime’s brutality. There is a steady stream of condemnation from the rest of the world and a steady stream of invective from Iran’s leaders.

Increasingly, as the anger rages and the regime shows no sign of giving in, the question in Iran is: How — and when — will it end?

The protests were triggered by the news that Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman, had died in police custody. She had been arrested just days prior for not properly wearing her headscarf. As Grid has reported, what began as a protest about Amini has grown to include more general demands for women’s rights. In some cases, protesters have taken things far further — calling for an end to the rule of Iran’s supreme leader.

Meanwhile, all across Iran, individual acts of public disobedience have gone mainstream. Women are walking bareheaded in the streets, burning their hijabs and cutting their hair in a symbolic denunciation of the regime. Images of turbans being flipped off the heads of Iranian clerics have gone viral. Athletic teams are refusing to sing the national anthem — most recently Iran’s national team, at Monday’s World Cup match against England. And disparate ethnic groups — the Kurds in the northwest and the Baluchis in the southeast, who have been harassed for decades by the regime — are making common cause, issuing statements of support for one another and solidarity with the protesters.

Yet the regime shows no sign of buckling or relenting in any way. Its security forces fire live ammunition in the streets. Nearly every day, the number of dead rises. The latest count by the Oslo-based Iran Human Rights group stands at more than 340 dead, 43 of them children. Journalists, filmmakers, actors, singers and athletes have been seized, the internet has been tightly restricted, and thousands of demonstrators have been arrested, among them a number of teenagers who have already been sentenced to death.

With no signs of compromise evident on either side, what are the potential endgames in Iran?

Scenario 1: crackdown

There have been ample signs that a large-scale crackdown may be coming.

With a decisive majority, the Majles, or parliament, voted last month to teach the protesters a “hard lesson,” comparing them to ISIS terrorists. Some 14,000 protesters are in custody, according to the Hrana news agency, many of whom have been seen on video being beaten and bundled into police cars.

It’s not clear what was meant by “hard lesson,” and few believe the regime would carry out anything like that scale of executions. The government maintains that many of the detainees have been released. But the regime has already indicted more than 100 of those under arrest, and the judiciary has fast-tracked public trials, which can carry the death penalty. Five protesters have been given death sentences.

And yet thus far, the government’s retaliation, though harsh and often lethal, hasn’t approached the levels of brutality seen in past uprisings. The motorcycle brigades wielding long-bladed knives against tightly packed demonstrators, so effective against the 2009 Green Movement, haven’t been in evidence this time.

Why hasn’t the crackdown been harsher?

One answer probably involves the fact that women and schoolgirls are at the forefront of so many of the demonstrations. For that reason alone, the regime may have made a calculation that the most brutal option was more difficult this time around. Initially at least, the police did not use assault rifles, although more recently videos on social media have shown them using shotguns to fire directly into the crowds.

Another explanation has to do with the sheer breadth of the movement. Demonstrations have erupted in more than 230 cities and towns across the country, in many cases as pop-up gatherings of a few hundred or a few thousand protesters, rather than the organized millions that filled cities in the past. That has made blanket police control more challenging.

Increasingly, Iranian police are using high-tech surveillance to get around the problem. According to parliamentarian Mousa Ghazanfarabadi, Chinese companies have installed millions of cameras capable of facial recognition in more than 20 Iranian cities across Iran. The cameras link to biometric data on identity cards that all Iranians must carry, making it easy for the authorities to find and arrest protesters without confronting them in the streets.

An Iranian political observer who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal indicated there was another, more insidious reason the crackdown had been lighter than in the past. The security services, she said, were preparing for the long haul, and holding younger recruits back until they are needed for a more forceful response. A leaked tape circulated on social media suggested military planners were worried the rookies didn’t have the stomach to attack the mothers and girls protesting in their neighborhoods and, therefore, should be kept in reserve. It may also be that a historical memory is influencing the security services’ current tactics. In the revolution that overthrew the shah in 1979, demonstrators appealed to young soldiers to join them, placing flowers in the barrels of their guns; a video currently circulating on social media, showing women handing out red flowers in Tehran to security forces, indicates the protesters are using this tactic again.

Precedent suggests a bigger crackdown is likely at some point. The Islamic Republic has no history of compromise on such matters and has only grown more rigid over time. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi has stated categorically that until the country returns to stability and security, there can be no progress. And he and other leaders have made it clear that if the demonstrators don’t stop, they will continue to condemn them as foreign stooges, tools of the U.S. and Israel, and then use the force necessary to dismantle them.

Scenario 2: The protests peter out

In some ways, the protesters have achieved what they wanted. Women all over the country now walk the streets without veils, jog in parks and eat in cafes with men who are not blood relatives. All three activities are against the law, punishable by severe fines or detention, and yet in many places they are going unpunished. For these reasons, some protesters argue that the war has been won and that it would be irresponsible to risk more lives for the sake of other goals.

One problem for the protesters involves a kind of “mission creep” within the movement. While calls to remove the mandatory hijab rule have been popular, fewer Iranians support the demands for regime change. Surveys generally show that only 34 percent of the population support a secular republic, while 28 percent still support an Islamic one; others say they aren’t sure. Iranian reformists, for example, who were behind the 2009 Green Movement and signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the nuclear deal) under former Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, believe in change from within and don’t condone a separation of church and state.

What is clear is that since the protests gained steam, attitudes among the population have been shifting. Satisfaction with the ultraconservative Raisi has dropped from 75 percent last year to under 20 percent now, with women expressing the highest rates of dissatisfaction. More than 50 percent of Iranians say they support street demonstrations and civil disobedience in the name of fighting corruption and improving the economy; it’s not clear they want the system overthrown.

Mother Nature may also play a role in the immediate future of the protest movement. Iran’s winters are brutal — snowy, icy and cold — and in many parts of the world and many moments in history, nasty weather has been a deterrent to protest. Things may calm or peter out simply because of the whims of an Iranian winter.

The most compelling argument against a long, drawn-out protest, however, involves the movement’s lack of leadership and organization. Ironically, it’s also part of the reason why it’s hard for the regime to snuff out the protests; there’s no obvious standard-bearer and no headquarters to shut down. Several Iranian analysts, having observed the failures of the leaderless Arab Spring, note that unless the movement develops a clear plan to take power, its decentralized nature may ultimately be its undoing.

Not surprisingly, supporters of the protests disagree. And there are some signs of a loose organization taking shape among youth and activist groups. A recent call for fresh protests was issued from seven cities, representing every part of Iran, each using the same language. “We will start from high schools, universities and markets,” the messages read, “and continue with neighborhood-centered gatherings and then move to the main city squares.”

Given how quickly the protest movement has grown and spread, it’s hard to imagine it will fade away completely and permanently. Instead, the movement may go into hibernation, only to regroup and rise again.

Scenario 3: civil war

So far, the protests have been an internal movement led by Iranians in Iran. No outsiders have been involved. But the diverse ethnic makeup of the country, its religious complexity and the deep ideological divisions between those in power and those in the streets could, with outside interference, devolve into a brutal civil war.

It’s a scenario some observers think is inevitable. So many players over the years, both inside and outside Iran, have advocated for regime change. Now they may see their chance.

Already, arms smuggling to anti-regime elements in the southern oil-rich province of Khuzestan has picked up since the protests began. Long viewed by Iran’s neighbors as a prize ripe for picking, Khuzestan has a large Sunni Arab population with a reputation for restlessness. Saudi and Israeli clandestine funding is supporting separatist movements in the region, according to European court documents. Israel and Saudi Arabia have made no secret of the fact that they would welcome a different government in Tehran.

Then there are the opposition groups outside the country that have spent years offering alternative scenarios for governing Iran, and which may now see a chance to put them into action. These include monarchists, who back the former crown prince of Iran, Reza Pahlavi, currently living in exile in the United States. Pahlavi nostalgia is high among the successful diaspora living in Los Angeles, and the prince enjoys a following inside Iran, with some calling for the return of the monarchy during demonstrations in 2019.

An utterly different group, the MEK or People’s Mojahedin, is another significant opposition force with activists both inside and outside Iran. Also known as the National Council of Resistance of Iran, the MEK is a cult-like militia that the U.S. and U.K. governments once branded as terrorists but now view as a useful group to work with. The MEK became best known for leaking Iran’s nuclear plans in 1992 and for its effective lobbying during the Trump years, when aides to then-President Donald Trump, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani and then-National Security Adviser John Bolton, viewed the group as the best alternative to the Islamic Republic.

Viscerally opposed to each other, the monarchists and the MEK both have access to funds as well as to officials in the U.S. and Europe.

Should any of these players get involved with local groups that see the protests as only the first step in a bigger fight, it could ignite a nasty conflict inside Iran.

A clash this weekend in the Iranian Kurdish town of Mahabad gave a hint of what might lie ahead. Riot police drove tanks into the city center and fired at demonstrators, according to eyewitness accounts, prompting Secretary of State Antony Blinken to condemn Iran’s escalating violence. The regime denied responsibility; and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the backbone of the country’s security system, said, “Those who want to dismantle the country are aiming to incite a civil war.” The IRGC is already blaming foreign interference for some of the bloodshed.

So far, the demonstrators have not been seen carrying arms. But Bolton said on BBC Persian over the weekend that arms are being smuggled across the Kurdish border, headed for what he referred to only as “the opposition.”

If that does happen — and handguns and rifles arrive in growing quantities across the borders, then the protests led by young women swinging their hair could be just the first act of a far more significant upheaval in Iran. And if a next act features armed groups, a civil war could turn the country into an inferno.

Scenario 4: wild card — an ailing supreme leader

The protests are coming at an awkward moment for the ruling elite. The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the most powerful figure in Iran, is 82 years old and rumored to have cancer. Behind the scenes, a competition for succession is already in full swing. Khamenei’s death would unsettle an already tense and dangerous situation.

No obvious leader to Khamenei has emerged, and the likely candidates — Raisi and Mojtaba Khamenei, a son of the supreme leader — are both unpopular. Furthermore, according to the Iranian constitution’s requirements, they are also both unqualified. Neither has the religious credentials necessary to lead the Islamic “ummah” or community, and Mojtaba has not filled the requirement of serving in public office. Meanwhile, the idea of hereditary succession is anathema to many of the powerful clerics, who want no whiff of monarchical tradition to reassert itself under the umbrella of the Islamic Republic. The Iranian people don’t like the idea either; in a recent survey, 78 percent of the population opposed hereditary succession. Yet over the three decades he has been leader, Khamenei has ousted his critics and surrounded himself with politically like-minded ultra-hardliners. His handpicked successor, regardless of qualifications, will likely be the one ultimately chosen.

While Khamenei is still alive, the protesters’ demands to terminate the Islamic Republic and remove the supreme leader are putting pressure on the clerics to act. They need to find a solution to the turmoil in the streets, but equally important, they must strengthen their hand against the Revolutionary Guard, which is increasingly threatening their control.

That’s because the Revolutionary Guard is the heavyweight in this brawl, the fiercest of Iran’s security forces, and a group that sees opportunity in capitalizing on the unrest to tighten its hold over the regime. If Khamenei were to die, the Revolutionary Guard would impose a curfew, send tanks into the streets, and ensure the government didn’t devolve into chaos.

Khamenei has always said that a smooth transition would be important to his legacy. One option would be the appointment of a council that would include hard-liners, reformists and other representatives; but the Revolutionary Guard might just seize power and appoint a figurehead as supreme leader, someone to rubber-stamp the the Revolutionary Guard’s rule. That would almost certainly spark a messy and perhaps violent period of transition.

Of course the protesters will also see opportunity in the death of the supreme leader — an opportunity to push their demands and appeal to the international community to help them change Iran’s trajectory. And the hope for Iranians is that with a population that is 96 percent literate, and which has for decades experienced the pitfalls of bad leadership and bad management, the protesters may now be able to win some of those demands. It is no small thing that these peaceful demonstrations have now touched every corner of the country, supported by men but led by women — and that fact alone gives rise to the hope that what ensues is not a bloodbath but a new form of inclusive peace and democracy. The outside world would help by lifting many of the punishing sanctions against the country.

In this scenario, the bravery of those standing up to the regime and their insistence on peace, rather than violence, could transform that hope into a blueprint for a new form of government.

It may be a long shot.

But it is possible.

Thanks to Alicia Benjamin for copy editing this article.

:quality(100)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thesummit/c65d89e4-b58a-4d85-8ee0-6a7351b34d12.jpg)

Roxane Farmanfarmaian

Special Contributor

Roxane Farmanfarmaian is director of international studies and global politics at the University of Cambridge Institute for Continuing Education and a senior research fellow at King’s College London.

From a brutal crackdown to civil war, an expert looks at scenarios for how a current wave of protests might unfold.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/LG7CAIFIXFA5JNSJKU6EJATMKI.jpg)

Iranian protesters march down a street in Tehran, Iran, on Oct. 1.

Contributor/Getty Images

Roxane Farmanfarmaian

Special Contributor

November 22, 2022

It’s been more than two months. There are daily protests against the regime in Iran in several parts of the country and daily reminders of the regime’s brutality. There is a steady stream of condemnation from the rest of the world and a steady stream of invective from Iran’s leaders.

Increasingly, as the anger rages and the regime shows no sign of giving in, the question in Iran is: How — and when — will it end?

The protests were triggered by the news that Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman, had died in police custody. She had been arrested just days prior for not properly wearing her headscarf. As Grid has reported, what began as a protest about Amini has grown to include more general demands for women’s rights. In some cases, protesters have taken things far further — calling for an end to the rule of Iran’s supreme leader.

Meanwhile, all across Iran, individual acts of public disobedience have gone mainstream. Women are walking bareheaded in the streets, burning their hijabs and cutting their hair in a symbolic denunciation of the regime. Images of turbans being flipped off the heads of Iranian clerics have gone viral. Athletic teams are refusing to sing the national anthem — most recently Iran’s national team, at Monday’s World Cup match against England. And disparate ethnic groups — the Kurds in the northwest and the Baluchis in the southeast, who have been harassed for decades by the regime — are making common cause, issuing statements of support for one another and solidarity with the protesters.

Yet the regime shows no sign of buckling or relenting in any way. Its security forces fire live ammunition in the streets. Nearly every day, the number of dead rises. The latest count by the Oslo-based Iran Human Rights group stands at more than 340 dead, 43 of them children. Journalists, filmmakers, actors, singers and athletes have been seized, the internet has been tightly restricted, and thousands of demonstrators have been arrested, among them a number of teenagers who have already been sentenced to death.

With no signs of compromise evident on either side, what are the potential endgames in Iran?

Scenario 1: crackdown

There have been ample signs that a large-scale crackdown may be coming.

With a decisive majority, the Majles, or parliament, voted last month to teach the protesters a “hard lesson,” comparing them to ISIS terrorists. Some 14,000 protesters are in custody, according to the Hrana news agency, many of whom have been seen on video being beaten and bundled into police cars.

It’s not clear what was meant by “hard lesson,” and few believe the regime would carry out anything like that scale of executions. The government maintains that many of the detainees have been released. But the regime has already indicted more than 100 of those under arrest, and the judiciary has fast-tracked public trials, which can carry the death penalty. Five protesters have been given death sentences.

And yet thus far, the government’s retaliation, though harsh and often lethal, hasn’t approached the levels of brutality seen in past uprisings. The motorcycle brigades wielding long-bladed knives against tightly packed demonstrators, so effective against the 2009 Green Movement, haven’t been in evidence this time.

Why hasn’t the crackdown been harsher?

One answer probably involves the fact that women and schoolgirls are at the forefront of so many of the demonstrations. For that reason alone, the regime may have made a calculation that the most brutal option was more difficult this time around. Initially at least, the police did not use assault rifles, although more recently videos on social media have shown them using shotguns to fire directly into the crowds.

Another explanation has to do with the sheer breadth of the movement. Demonstrations have erupted in more than 230 cities and towns across the country, in many cases as pop-up gatherings of a few hundred or a few thousand protesters, rather than the organized millions that filled cities in the past. That has made blanket police control more challenging.

Increasingly, Iranian police are using high-tech surveillance to get around the problem. According to parliamentarian Mousa Ghazanfarabadi, Chinese companies have installed millions of cameras capable of facial recognition in more than 20 Iranian cities across Iran. The cameras link to biometric data on identity cards that all Iranians must carry, making it easy for the authorities to find and arrest protesters without confronting them in the streets.

An Iranian political observer who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal indicated there was another, more insidious reason the crackdown had been lighter than in the past. The security services, she said, were preparing for the long haul, and holding younger recruits back until they are needed for a more forceful response. A leaked tape circulated on social media suggested military planners were worried the rookies didn’t have the stomach to attack the mothers and girls protesting in their neighborhoods and, therefore, should be kept in reserve. It may also be that a historical memory is influencing the security services’ current tactics. In the revolution that overthrew the shah in 1979, demonstrators appealed to young soldiers to join them, placing flowers in the barrels of their guns; a video currently circulating on social media, showing women handing out red flowers in Tehran to security forces, indicates the protesters are using this tactic again.

Precedent suggests a bigger crackdown is likely at some point. The Islamic Republic has no history of compromise on such matters and has only grown more rigid over time. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi has stated categorically that until the country returns to stability and security, there can be no progress. And he and other leaders have made it clear that if the demonstrators don’t stop, they will continue to condemn them as foreign stooges, tools of the U.S. and Israel, and then use the force necessary to dismantle them.

Scenario 2: The protests peter out

In some ways, the protesters have achieved what they wanted. Women all over the country now walk the streets without veils, jog in parks and eat in cafes with men who are not blood relatives. All three activities are against the law, punishable by severe fines or detention, and yet in many places they are going unpunished. For these reasons, some protesters argue that the war has been won and that it would be irresponsible to risk more lives for the sake of other goals.

One problem for the protesters involves a kind of “mission creep” within the movement. While calls to remove the mandatory hijab rule have been popular, fewer Iranians support the demands for regime change. Surveys generally show that only 34 percent of the population support a secular republic, while 28 percent still support an Islamic one; others say they aren’t sure. Iranian reformists, for example, who were behind the 2009 Green Movement and signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the nuclear deal) under former Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, believe in change from within and don’t condone a separation of church and state.

What is clear is that since the protests gained steam, attitudes among the population have been shifting. Satisfaction with the ultraconservative Raisi has dropped from 75 percent last year to under 20 percent now, with women expressing the highest rates of dissatisfaction. More than 50 percent of Iranians say they support street demonstrations and civil disobedience in the name of fighting corruption and improving the economy; it’s not clear they want the system overthrown.

Mother Nature may also play a role in the immediate future of the protest movement. Iran’s winters are brutal — snowy, icy and cold — and in many parts of the world and many moments in history, nasty weather has been a deterrent to protest. Things may calm or peter out simply because of the whims of an Iranian winter.

The most compelling argument against a long, drawn-out protest, however, involves the movement’s lack of leadership and organization. Ironically, it’s also part of the reason why it’s hard for the regime to snuff out the protests; there’s no obvious standard-bearer and no headquarters to shut down. Several Iranian analysts, having observed the failures of the leaderless Arab Spring, note that unless the movement develops a clear plan to take power, its decentralized nature may ultimately be its undoing.

Not surprisingly, supporters of the protests disagree. And there are some signs of a loose organization taking shape among youth and activist groups. A recent call for fresh protests was issued from seven cities, representing every part of Iran, each using the same language. “We will start from high schools, universities and markets,” the messages read, “and continue with neighborhood-centered gatherings and then move to the main city squares.”

Given how quickly the protest movement has grown and spread, it’s hard to imagine it will fade away completely and permanently. Instead, the movement may go into hibernation, only to regroup and rise again.

Scenario 3: civil war

So far, the protests have been an internal movement led by Iranians in Iran. No outsiders have been involved. But the diverse ethnic makeup of the country, its religious complexity and the deep ideological divisions between those in power and those in the streets could, with outside interference, devolve into a brutal civil war.

It’s a scenario some observers think is inevitable. So many players over the years, both inside and outside Iran, have advocated for regime change. Now they may see their chance.

Already, arms smuggling to anti-regime elements in the southern oil-rich province of Khuzestan has picked up since the protests began. Long viewed by Iran’s neighbors as a prize ripe for picking, Khuzestan has a large Sunni Arab population with a reputation for restlessness. Saudi and Israeli clandestine funding is supporting separatist movements in the region, according to European court documents. Israel and Saudi Arabia have made no secret of the fact that they would welcome a different government in Tehran.

Then there are the opposition groups outside the country that have spent years offering alternative scenarios for governing Iran, and which may now see a chance to put them into action. These include monarchists, who back the former crown prince of Iran, Reza Pahlavi, currently living in exile in the United States. Pahlavi nostalgia is high among the successful diaspora living in Los Angeles, and the prince enjoys a following inside Iran, with some calling for the return of the monarchy during demonstrations in 2019.

An utterly different group, the MEK or People’s Mojahedin, is another significant opposition force with activists both inside and outside Iran. Also known as the National Council of Resistance of Iran, the MEK is a cult-like militia that the U.S. and U.K. governments once branded as terrorists but now view as a useful group to work with. The MEK became best known for leaking Iran’s nuclear plans in 1992 and for its effective lobbying during the Trump years, when aides to then-President Donald Trump, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani and then-National Security Adviser John Bolton, viewed the group as the best alternative to the Islamic Republic.

Viscerally opposed to each other, the monarchists and the MEK both have access to funds as well as to officials in the U.S. and Europe.

Should any of these players get involved with local groups that see the protests as only the first step in a bigger fight, it could ignite a nasty conflict inside Iran.

A clash this weekend in the Iranian Kurdish town of Mahabad gave a hint of what might lie ahead. Riot police drove tanks into the city center and fired at demonstrators, according to eyewitness accounts, prompting Secretary of State Antony Blinken to condemn Iran’s escalating violence. The regime denied responsibility; and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the backbone of the country’s security system, said, “Those who want to dismantle the country are aiming to incite a civil war.” The IRGC is already blaming foreign interference for some of the bloodshed.

So far, the demonstrators have not been seen carrying arms. But Bolton said on BBC Persian over the weekend that arms are being smuggled across the Kurdish border, headed for what he referred to only as “the opposition.”

If that does happen — and handguns and rifles arrive in growing quantities across the borders, then the protests led by young women swinging their hair could be just the first act of a far more significant upheaval in Iran. And if a next act features armed groups, a civil war could turn the country into an inferno.

Scenario 4: wild card — an ailing supreme leader

The protests are coming at an awkward moment for the ruling elite. The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the most powerful figure in Iran, is 82 years old and rumored to have cancer. Behind the scenes, a competition for succession is already in full swing. Khamenei’s death would unsettle an already tense and dangerous situation.

No obvious leader to Khamenei has emerged, and the likely candidates — Raisi and Mojtaba Khamenei, a son of the supreme leader — are both unpopular. Furthermore, according to the Iranian constitution’s requirements, they are also both unqualified. Neither has the religious credentials necessary to lead the Islamic “ummah” or community, and Mojtaba has not filled the requirement of serving in public office. Meanwhile, the idea of hereditary succession is anathema to many of the powerful clerics, who want no whiff of monarchical tradition to reassert itself under the umbrella of the Islamic Republic. The Iranian people don’t like the idea either; in a recent survey, 78 percent of the population opposed hereditary succession. Yet over the three decades he has been leader, Khamenei has ousted his critics and surrounded himself with politically like-minded ultra-hardliners. His handpicked successor, regardless of qualifications, will likely be the one ultimately chosen.

While Khamenei is still alive, the protesters’ demands to terminate the Islamic Republic and remove the supreme leader are putting pressure on the clerics to act. They need to find a solution to the turmoil in the streets, but equally important, they must strengthen their hand against the Revolutionary Guard, which is increasingly threatening their control.

That’s because the Revolutionary Guard is the heavyweight in this brawl, the fiercest of Iran’s security forces, and a group that sees opportunity in capitalizing on the unrest to tighten its hold over the regime. If Khamenei were to die, the Revolutionary Guard would impose a curfew, send tanks into the streets, and ensure the government didn’t devolve into chaos.

Khamenei has always said that a smooth transition would be important to his legacy. One option would be the appointment of a council that would include hard-liners, reformists and other representatives; but the Revolutionary Guard might just seize power and appoint a figurehead as supreme leader, someone to rubber-stamp the the Revolutionary Guard’s rule. That would almost certainly spark a messy and perhaps violent period of transition.

Of course the protesters will also see opportunity in the death of the supreme leader — an opportunity to push their demands and appeal to the international community to help them change Iran’s trajectory. And the hope for Iranians is that with a population that is 96 percent literate, and which has for decades experienced the pitfalls of bad leadership and bad management, the protesters may now be able to win some of those demands. It is no small thing that these peaceful demonstrations have now touched every corner of the country, supported by men but led by women — and that fact alone gives rise to the hope that what ensues is not a bloodbath but a new form of inclusive peace and democracy. The outside world would help by lifting many of the punishing sanctions against the country.

In this scenario, the bravery of those standing up to the regime and their insistence on peace, rather than violence, could transform that hope into a blueprint for a new form of government.

It may be a long shot.

But it is possible.

Thanks to Alicia Benjamin for copy editing this article.

:quality(100)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thesummit/c65d89e4-b58a-4d85-8ee0-6a7351b34d12.jpg)

Roxane Farmanfarmaian

Special Contributor

Roxane Farmanfarmaian is director of international studies and global politics at the University of Cambridge Institute for Continuing Education and a senior research fellow at King’s College London.

No comments:

Post a Comment