Luka Mesec on the Slovenian Left’s rise from student protests to a party of government

AUTHORS

Luka Mesec, Joseph Beswick

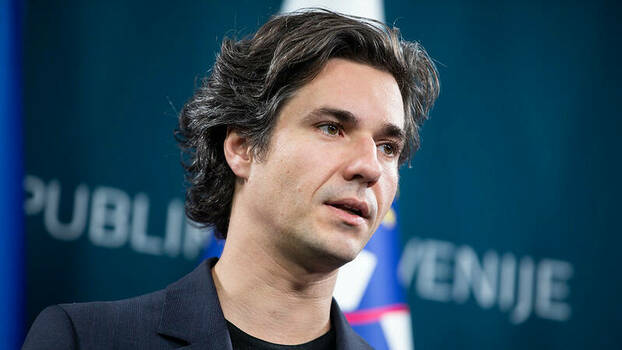

Luka Mesec, Deputy Prime Minister of Slovenia, at a government press

conference in October 2022.

Photo: Flickr/Vlada Republike Slovenije

During the democratic socialist wave that swept Western Europe in the 2010s, most international attention was focused on the big names in the big countries: Pablo Iglesias in Spain, Jeremy Corbyn in Great Britiain, and Jean-Luc Melénchon in France, to name a few. The rise of new left-wing formations and their success in shifting political debates in their countries to the Left inspired millions and gave many the impression that history was once again on socialism’s side.

But over the last few years, many of those new left parties have beaten hasty retreats. Some leaders have resigned, others find themselves on the defensive. In the small Southeast European country of Slovenia, however, the Left seems to be hanging on. The democratic socialist party Levica (Slovenian for “the Left”), which emerged out of anti-austerity protests in the country one decade earlier, is now a part of the new government and pushing forward its policies in several key ministries.

Party leader and Slovenian Deputy Prime Minister Luka Mesec was recently in the UK for the World Transformed Festival, where he spoke with the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Joe Beswick about the party’s trajectory, its plans for government, and how socialism can go mainstream in Slovenia and across Europe.

Levica has existed as a party since 2017, but its history dates back further, and is of course closely related to Slovenian politics since the collapse of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Can you give us a brief overview of how politics in Slovenia has developed over the last three decades?

Luka Mesec is Deputy Prime Minister of Slovenia and Minister of Family, Labour, and Social Affairs. He has lead the Slovenian socialist party Levica since its founding in 2017.

I would divide those three decades into three periods. The first period was the transition, from 1991 until accession to the EU or adoption of the euro, which happened in 2004 and 2007. In those years, Slovenia was the only former socialist country in Europe that decided not to go “all-in” with the shock doctrine, but instead established a welfare state according to the Austrian or German model. It was quite successful — we were the most successful Eastern European economy, and the welfare state is still alive and well. In terms of purchasing power, the bottom half of the Slovenian population lives better than their counterparts in England or the US.

However, the next 15 years were much more troubled. Those were basically the times of crisis. After the financial collapse in 2008, Slovenia suffered like all of the southern European economies. There was a debt crisis, and a lot of big firms and banks went bankrupt. The banks were nationalized, followed by austerity measures. Then, the crises accumulated — first the austerity measures, then fierce political polarization, and the migrant crisis, which of course caused new political fights, and then, at the end, COVID.

Now I think we are in a new period. The centre-left is in power again after 15 years, ruled by a new party called Svoboda, the Freedom Party. The prime minister, Robert Golub, turned out to have left-leaning inclinations. We are removing the barbed wire from our border with Croatia, the tax reform looks progressive for now, and Levica entered the government for the first time. We control the Ministry for Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities as well as the Ministry for Culture. We will also invent a new system of social housing.

At least for the moment, it seems that the crises of the past decades are over. New crises are looming, but for now, the government and the coalition looks stable.

Can you tell us more about the origins of Levica? Who formed it, what were the main constituencies behind, and how did you yourself come to be a part of it?

Levica is basically the child of the crisis that I was describing in the last decade. We were born out of a student movement in 2011. Back then, I was a 25-year-old activist. When I was 27, we formed the party, and I entered the parliament for the first time in 2014. Since then, we have built up the party as a political force.

Levica began as a party with Marxist tendencies, but increasingly I’m more interested in post-Keynesian policies. We’re not only a “social” party — we are also an environmental party and a party that strongly defended democracy against the previous government. We contributed a lot to the fall of that government, which is how we gained the legitimacy to be part of the current government.

We have to think about how to embed socialist ideas in the present liberal environment, because the default ideology is liberalism everywhere in Europe.

I decided to go into activism because when I started university in 2007, it seemed like the world was collapsing — our generation would not get decent jobs, the housing crisis was looming, and the future looked grim. We decided that we have to change something and formed various activist movements. We tried direct democracy, we tried to influence politics via protest movements, and so on. Ultimately, we decided that a party was the way to go.

Back then I was 27, and I had to get used to being a public persona that was warmly greeted by one part of the Slovenian public, but quite hated by others. I got used to it after eight years, but now, as deputy prime minister, the pressure is ten times greater than before. We are leading our ministries with competence and public opinion agrees with what we are doing on a political level, but I worry about our society.

When Guy Debord wrote The Society of Spectacle, I don’t think he imagined what scope this spectacle would take on 60 years later. What I’m most afraid of right now is that regardless of what we do in terms of policies, there is a narrative that is completely detached from it. I have to battle spin cycles and false accusations all the time. It’s similar to the smears Jeremy Corbyn faced when he was close to power.

Speaking of challenges Corbyn faced, what about Levica’s social base? Is it fair to say that your constituency is largely urban, educated, left-wing people? And what success have you had building a coalition with the traditional industrial working class?

It is challenging, because the right wing has the same agenda everywhere. They say that the future will be a fight between globalists and nationalists, and they focus their fire on the capital cities. They say “they are for Ljubljana, we are for Slovenia”. And their narrative is quite successful.

In Ljubljana, we can get maybe 20 percent, and in other bigger cities we can get 10 or 15 percent, but the Right dominates in the countryside. We are looking for ways to break their hold, and I believe the government is a position that can help. When you hold a ministerial position, you’re welcome everywhere, no matter what political party you’re from. Mayors and local authorities welcome you because they don’t want to have bad relations with the state. I’m using that to try to present a different picture than what is being depicted by right-wing propaganda.

We have to tackle those fears. When people are not afraid anymore, we can start talking about what future we want to build together.

It sounds like the Left in the Balkans went from a protest movement to an electoral formation, a path the Left has taken in many parts of the world over the last decade. What were some of the main challenges in that process?

When a movement transforms into a political party and enters parliament but stays in the opposition, its role is not very different from what it was before. Being an opposition member of parliament is still an activist position. They might try to push you to moderate your tone, but you can still say whatever you want and try to pull the Overton window to the left.

Once you’re in government, it becomes more complicated, because the arithmetic of power is much more complicated. I figured out very quickly that from now on, every word that I say can cause a media frenzy. But it’s not just the media that you have to be careful about. There are lots of sensitive relations between members of the coalition, various ministries in the government, opposition, the public, and so on. You have to calculate all the time how to pitch your agenda without sparking too much of a backlash.

Speaking of backlash, when the new government was first announced, you were slated to head a new “Ministry for Solidarity-Based Futures”. Recently, it was announced that the ministry would not be created after all. Was that a political battle that Levica lost?

When we formed the government, we decided to create new ministries: a Ministry for Climate, a Ministry for the Protection of Natural Resources, a Ministry for Digitalization, and the Ministry for a Solidarity-Based Future. The right wing, which is of course allergic to Levica, decided to call for a national referendum against the Ministry for Solidarity-Based Futures.

Whether it’s Corbyn, Podemos, or Levica — there is space for socialist interventions. The question is whether a new variant of socialism can become the predominant force in national politics.

I’m currently the Minister of Labour and the Welfare State, and we decided that we could just expand this ministry to include housing, long-term care, and economic democracy and rename it. It’s mostly a question of semantics, but that was publicly very well accepted because it showed that we’re willing to do smart compromises.

Electoral politics is always about compromise and building coalitions, which can sometimes mean a de-radicalization of politics. You said that Levica went from a Marxist background to a more post-Keynesian approach. Do you think that’s been a price worth paying? Has the party made real change in government?

Yes, I believe so. We focused our agenda on issues that can be moved to the left or where new social systems could even be established. For instance, we cancelled an arms deal signed by the previous government that was worth 400 million euro, which is a lot of money for the Slovenian budget, nearly 1 percent of GDP. We also removed the barbed wire from the border with Croatia, which was unimaginable a year ago.

The new tax reform is interesting because it shifts the priorities of our social system, which was drifting towards precarization. We’ve made regular employment cheaper for young people under the age of 29, so we are transitioning more young people into regular employment. We are also establishing a mechanism of workers’ ownership, and some firms are already interested in it. So, we will basically relaunch the cooperative movement in Slovenia.

The other thing I’m really enthusiastic about is that we are starting a public housing policy — basically from zero. Those are all policies that would not happen without Levica in government, and I believe that if we do all of that in the next year or two, we will have a lot of good examples.

That all sounds very exciting. You mentioned “relaunching the cooperative movement” in Slovenia. On that note, what role does the legacy of Yugoslavian socialism play for Levica and for politics in Slovenia?

The legacy of Yugoslavia in Slovenia is not comparable to the legacy of the Soviet Union. In Slovenia there was a degree of free speech and things were in fact quite democratic, so people are not so negative towards Yugoslavia. If you ask Slovenians, about 70 percent say that Tito was a positive figure.

In that sense, socialism doesn’t scare people when talking about history, but it’s different when we’re talking about the present. At least among some parts of the public, they understand socialism as nationalizing small- and medium-sized businesses, or that we want to stop anyone from earning more than 3,000 euro per month, and so on. So, we have to think about how to embed socialist ideas in the present liberal environment, because the default ideology is liberalism everywhere in Europe.

But as I believe all of our examples show, whether it’s Corbyn, Podemos, or Levica — there is space for socialist interventions. The question is whether a new variant of socialism can become the predominant force in national politics. That’s why I believe it was worth going into government, because every attempt is a test that will reveal both mistakes and successes.

BOOK | 07/2021The New Balkan Left

A new volume from the RLS takes stock of its struggles, successes, and failures

During the democratic socialist wave that swept Western Europe in the 2010s, most international attention was focused on the big names in the big countries: Pablo Iglesias in Spain, Jeremy Corbyn in Great Britiain, and Jean-Luc Melénchon in France, to name a few. The rise of new left-wing formations and their success in shifting political debates in their countries to the Left inspired millions and gave many the impression that history was once again on socialism’s side.

But over the last few years, many of those new left parties have beaten hasty retreats. Some leaders have resigned, others find themselves on the defensive. In the small Southeast European country of Slovenia, however, the Left seems to be hanging on. The democratic socialist party Levica (Slovenian for “the Left”), which emerged out of anti-austerity protests in the country one decade earlier, is now a part of the new government and pushing forward its policies in several key ministries.

Party leader and Slovenian Deputy Prime Minister Luka Mesec was recently in the UK for the World Transformed Festival, where he spoke with the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Joe Beswick about the party’s trajectory, its plans for government, and how socialism can go mainstream in Slovenia and across Europe.

Levica has existed as a party since 2017, but its history dates back further, and is of course closely related to Slovenian politics since the collapse of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Can you give us a brief overview of how politics in Slovenia has developed over the last three decades?

Luka Mesec is Deputy Prime Minister of Slovenia and Minister of Family, Labour, and Social Affairs. He has lead the Slovenian socialist party Levica since its founding in 2017.

I would divide those three decades into three periods. The first period was the transition, from 1991 until accession to the EU or adoption of the euro, which happened in 2004 and 2007. In those years, Slovenia was the only former socialist country in Europe that decided not to go “all-in” with the shock doctrine, but instead established a welfare state according to the Austrian or German model. It was quite successful — we were the most successful Eastern European economy, and the welfare state is still alive and well. In terms of purchasing power, the bottom half of the Slovenian population lives better than their counterparts in England or the US.

However, the next 15 years were much more troubled. Those were basically the times of crisis. After the financial collapse in 2008, Slovenia suffered like all of the southern European economies. There was a debt crisis, and a lot of big firms and banks went bankrupt. The banks were nationalized, followed by austerity measures. Then, the crises accumulated — first the austerity measures, then fierce political polarization, and the migrant crisis, which of course caused new political fights, and then, at the end, COVID.

Now I think we are in a new period. The centre-left is in power again after 15 years, ruled by a new party called Svoboda, the Freedom Party. The prime minister, Robert Golub, turned out to have left-leaning inclinations. We are removing the barbed wire from our border with Croatia, the tax reform looks progressive for now, and Levica entered the government for the first time. We control the Ministry for Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities as well as the Ministry for Culture. We will also invent a new system of social housing.

At least for the moment, it seems that the crises of the past decades are over. New crises are looming, but for now, the government and the coalition looks stable.

Can you tell us more about the origins of Levica? Who formed it, what were the main constituencies behind, and how did you yourself come to be a part of it?

Levica is basically the child of the crisis that I was describing in the last decade. We were born out of a student movement in 2011. Back then, I was a 25-year-old activist. When I was 27, we formed the party, and I entered the parliament for the first time in 2014. Since then, we have built up the party as a political force.

Levica began as a party with Marxist tendencies, but increasingly I’m more interested in post-Keynesian policies. We’re not only a “social” party — we are also an environmental party and a party that strongly defended democracy against the previous government. We contributed a lot to the fall of that government, which is how we gained the legitimacy to be part of the current government.

We have to think about how to embed socialist ideas in the present liberal environment, because the default ideology is liberalism everywhere in Europe.

I decided to go into activism because when I started university in 2007, it seemed like the world was collapsing — our generation would not get decent jobs, the housing crisis was looming, and the future looked grim. We decided that we have to change something and formed various activist movements. We tried direct democracy, we tried to influence politics via protest movements, and so on. Ultimately, we decided that a party was the way to go.

Back then I was 27, and I had to get used to being a public persona that was warmly greeted by one part of the Slovenian public, but quite hated by others. I got used to it after eight years, but now, as deputy prime minister, the pressure is ten times greater than before. We are leading our ministries with competence and public opinion agrees with what we are doing on a political level, but I worry about our society.

When Guy Debord wrote The Society of Spectacle, I don’t think he imagined what scope this spectacle would take on 60 years later. What I’m most afraid of right now is that regardless of what we do in terms of policies, there is a narrative that is completely detached from it. I have to battle spin cycles and false accusations all the time. It’s similar to the smears Jeremy Corbyn faced when he was close to power.

Speaking of challenges Corbyn faced, what about Levica’s social base? Is it fair to say that your constituency is largely urban, educated, left-wing people? And what success have you had building a coalition with the traditional industrial working class?

It is challenging, because the right wing has the same agenda everywhere. They say that the future will be a fight between globalists and nationalists, and they focus their fire on the capital cities. They say “they are for Ljubljana, we are for Slovenia”. And their narrative is quite successful.

In Ljubljana, we can get maybe 20 percent, and in other bigger cities we can get 10 or 15 percent, but the Right dominates in the countryside. We are looking for ways to break their hold, and I believe the government is a position that can help. When you hold a ministerial position, you’re welcome everywhere, no matter what political party you’re from. Mayors and local authorities welcome you because they don’t want to have bad relations with the state. I’m using that to try to present a different picture than what is being depicted by right-wing propaganda.

We have to tackle those fears. When people are not afraid anymore, we can start talking about what future we want to build together.

It sounds like the Left in the Balkans went from a protest movement to an electoral formation, a path the Left has taken in many parts of the world over the last decade. What were some of the main challenges in that process?

When a movement transforms into a political party and enters parliament but stays in the opposition, its role is not very different from what it was before. Being an opposition member of parliament is still an activist position. They might try to push you to moderate your tone, but you can still say whatever you want and try to pull the Overton window to the left.

Once you’re in government, it becomes more complicated, because the arithmetic of power is much more complicated. I figured out very quickly that from now on, every word that I say can cause a media frenzy. But it’s not just the media that you have to be careful about. There are lots of sensitive relations between members of the coalition, various ministries in the government, opposition, the public, and so on. You have to calculate all the time how to pitch your agenda without sparking too much of a backlash.

Speaking of backlash, when the new government was first announced, you were slated to head a new “Ministry for Solidarity-Based Futures”. Recently, it was announced that the ministry would not be created after all. Was that a political battle that Levica lost?

When we formed the government, we decided to create new ministries: a Ministry for Climate, a Ministry for the Protection of Natural Resources, a Ministry for Digitalization, and the Ministry for a Solidarity-Based Future. The right wing, which is of course allergic to Levica, decided to call for a national referendum against the Ministry for Solidarity-Based Futures.

Whether it’s Corbyn, Podemos, or Levica — there is space for socialist interventions. The question is whether a new variant of socialism can become the predominant force in national politics.

I’m currently the Minister of Labour and the Welfare State, and we decided that we could just expand this ministry to include housing, long-term care, and economic democracy and rename it. It’s mostly a question of semantics, but that was publicly very well accepted because it showed that we’re willing to do smart compromises.

Electoral politics is always about compromise and building coalitions, which can sometimes mean a de-radicalization of politics. You said that Levica went from a Marxist background to a more post-Keynesian approach. Do you think that’s been a price worth paying? Has the party made real change in government?

Yes, I believe so. We focused our agenda on issues that can be moved to the left or where new social systems could even be established. For instance, we cancelled an arms deal signed by the previous government that was worth 400 million euro, which is a lot of money for the Slovenian budget, nearly 1 percent of GDP. We also removed the barbed wire from the border with Croatia, which was unimaginable a year ago.

The new tax reform is interesting because it shifts the priorities of our social system, which was drifting towards precarization. We’ve made regular employment cheaper for young people under the age of 29, so we are transitioning more young people into regular employment. We are also establishing a mechanism of workers’ ownership, and some firms are already interested in it. So, we will basically relaunch the cooperative movement in Slovenia.

The other thing I’m really enthusiastic about is that we are starting a public housing policy — basically from zero. Those are all policies that would not happen without Levica in government, and I believe that if we do all of that in the next year or two, we will have a lot of good examples.

That all sounds very exciting. You mentioned “relaunching the cooperative movement” in Slovenia. On that note, what role does the legacy of Yugoslavian socialism play for Levica and for politics in Slovenia?

The legacy of Yugoslavia in Slovenia is not comparable to the legacy of the Soviet Union. In Slovenia there was a degree of free speech and things were in fact quite democratic, so people are not so negative towards Yugoslavia. If you ask Slovenians, about 70 percent say that Tito was a positive figure.

In that sense, socialism doesn’t scare people when talking about history, but it’s different when we’re talking about the present. At least among some parts of the public, they understand socialism as nationalizing small- and medium-sized businesses, or that we want to stop anyone from earning more than 3,000 euro per month, and so on. So, we have to think about how to embed socialist ideas in the present liberal environment, because the default ideology is liberalism everywhere in Europe.

But as I believe all of our examples show, whether it’s Corbyn, Podemos, or Levica — there is space for socialist interventions. The question is whether a new variant of socialism can become the predominant force in national politics. That’s why I believe it was worth going into government, because every attempt is a test that will reveal both mistakes and successes.

BOOK | 07/2021The New Balkan Left

A new volume from the RLS takes stock of its struggles, successes, and failures

No comments:

Post a Comment