VULCANOLOGY

Many Know of Mount Vesuvius. Few Realize There’s a More Destructive Volcano Right Next DoorStav Dimitropoulos

Fri, December 16, 2022

Few Know of the Most Destructive Volcano in ItalyWikimedia Commons

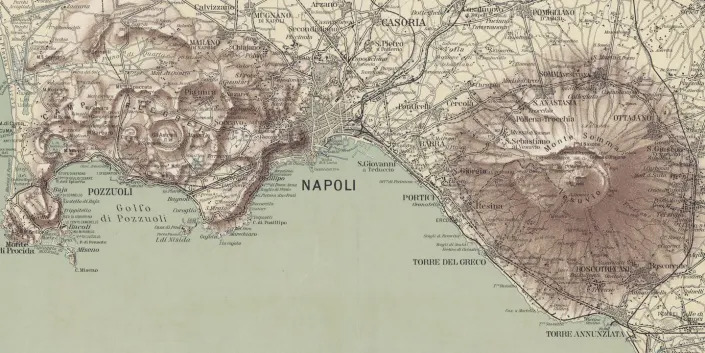

People living in the metropolitan area of Naples, Italy, are literally sandwiched between two active volcanoes.

Mount Vesuvius gets all the attention because of its destruction of ancient Pompeii, but it pales in comparison to Campi Flegrei, a bigger volcano to the west of Naples, whose awakening could wreak havoc on the area.

There is an emergency plan in case either erupts, but they are unclear and certainly not well-communicated; still, Neapolitans have a special relationship with their volcanoes.

Mount Vesuvius looms over the palatial Forum Romanum, the civic center of Pompeii, the ancient Roman city 25 kilometers southeast of Naples, in southwestern Italy. Looking at the collapsed peak of the 200,000-year-old volcano from a close distance is surreal.

Just like every visitor to the city’s ruins, I let the present slip through my grasp, fixating on Vesuvius and the past and death. How many of the 16,000 people who died that day in 79a.d. thought that the “extinct” volcano would one day eject a pyroclastic flow of scorching hot ash, lava, and gasses, burying everyone and everything in four to six meters of ash and pumice?

Vesuvius is not dead. Its most recent eruption in March 1944 buried three nearby villages in giant clouds of ash and other pyroclastic materials; miraculously, no one lost their life. Some scientists say it could well erupt in the 21st century, and that a 15-minute explosion could potentially ravage the entire 15-kilometer-wide Gulf of Naples, the touristy semicircular inlet along the southwestern coast of Italy, killing millions of people. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

A close-up view of Mount Vesuvius from the ancient city of Pompeii. Jonathan Perugia - Getty Images

Few of Pompeii’s awestruck visitors—myself included—realize that 35 kilometers from Vesuvius, to the west of Naples, lies a far bigger and stronger volcano—the eruption of which could make Vesuvius’s eruptions look like mere sparkles in comparison.

A Infrequent, But Greater Danger

The volcano’s Italian name is Campi Flegrei—in English it’s called Phlegraean Fields—which translates to “burning fields” or “fiery fields.” Located just opposite of Vesuvius, on the other side of Naples, Campi Flegrei lies mostly underground, which is why most tourists are oblivious to its existence and instead obsess over historic Vesuvius. But Campi Flegrei is the real giant, comprised of 24 craters and edifices, many of which are underwater in Pozzuoli Bay, at the northwestern end of the Gulf of Naples.

Campi Flegrei is often referred to as a supervolcano. It technically isn’t one, but it’s close. A supervolcano is able to produce an eruption of the highest magnitude, an 8 on the Volcano Explosivity Index. It means that the volcano has erupted at least once in the past, expelling more than 1,000 cubic kilometers of ejecta. Campi Flegrei’s biggest eruption, the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, is thought to have produced 181 to 285 cubic kilometers of ejecta, making it a magnitude 7. These inconceivably vast tephra emissions would blacken the atmosphere, diminishing solar radiation and plunging Earth into a global winter; plant growth would suffer and mass extinctions could follow.

An overhead view of Campi Flegrei. A series of craters outline the edge of the volcano’s caldera.Gallo Images - Getty Images

Still, Campi Flegrei is among the most dangerous volcanoes in Europe. To give you some perspective, its Campanian Ignimbrite eruption nearly 40,000 years ago disgorged plumes of ash and volcanic gas into the atmosphere, triggering a volcanic winter and lowering the Earth’s temperature by several degrees for many years—likely contributing to the extinction of the Neanderthals.

A Densely Populated Area

Five-hundred thousand people live in Campi Flegrei’s red zone, an area classified as extremely dangerous when it comes to the risk of pyroclastic flows, which includes at least 18 towns, according to the National Plan of Civil Protection for the Phlegraean Fields drawn up by the Civil Protection Department of the Italian government. In the event of an “alarm,” full evacuation is the only option for the inhabitants, the plan says.

A study published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research in 2019 also found that an underwater eruption of Campi Flegrei could (worst-case scenario) produce 100-foot tsunamis with the potential to obliterate Pozzuoli and Sorrento, small touristy towns overlooking the Gulf of Naples. (Pozzuoli also literally sits atop the volcano.)

Casts of the bodies of those entombed in ash during the 79AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, Pompeii. AFP - Getty Images

Think about it: Vesuvius on the one side, the Burning Fields on the other–the beautiful Neapolitan chaos is literally sandwiched between two active volcanos. Would it be far-fetched to think that the tragedy of Pompeii will repeat itself?

False Red Flags

Though Campi Flegrei last erupted in 1538, something weird happened in April of 2022: the sea around the volcano turned red. More accurately, an algae bloom reddened the volcanic crater lake of Averno (or Avernus), then spread to the water in the Gulf of Pozzuoli, and eventually out to the open sea. The algae bloom is a seasonal occurrence, but this year it was especially colorful. The extreme heat of volcanic activity can cause nutrients from deep underwater to come to the surface and act as fertilizer to organisms like algae and phytoplankton, as documented by a 2019 study on Hawaiian volcano Kīlauea published in Science. So, some scientists worried that this unexpectedly strong algae bloom was a sign of volcanic unrest.

The red waters of crater lake Averno, April 2022. KONTROLAB - Getty Images

But Lucia Pappalardo, senior researcher at Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, in the Vesuvius Observatory, Naples department, who co-authored a 2021 study on volcanic hazard in Italy, doesn’t believe Campi Flegrei will erupt any time soon.

“That the Averno lake inside Campi Flegrei turned red (and not the sea) is not related to volcanic activity but is a consequence of weather conditions,” Pappalardo tells Popular Mechanics. “Moreover, I don’t know any accredited scientific studies predicting an eruption in a short time.”

Predicting an Eruption

According to Pappalardo, what is currently underway at Campi Flegrei is the phenomenon called bradyseism—a combination of the Greek words “βραδύς” meaning slow and “σεισμός” meaning earthquake. In volcanology, bradyseism refers to a gradual uplift or descent of part of the Earth’s surface, caused by an underground magma chamber being filled or vacated, or because intense hydrothermal activity is taking place inside the caldera, a large, round depression in the ground created by the collapse of a volcanic landform.

Know Your Volcano Lingo

A caldera is similar to but typically much larger than a crater, and can encompass numerous craters and other “nested” calderas, as is the case with Campi Flegrei. The greater caldera of Campi Flegrei, formed during the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, is about 13 kilometers wide.

“Particularly from 2005 to today, the center of the caldera has risen by 98 centimeters,” says Pappalardo, or over 38 inches. In some cases, ground uplift can indeed be a precursor to an eruption, as was the case when Campi Flegrei last erupted in 1538 A.D. Yet, between 1970 to 1972 and 1982 to 1984, Campi Flegrei’s ground surface rose by about 3.5 meters (11.5 feet), and no eruption occurred–just considerable seismic activity.

“Thus, ground uplift is not the only parameter that has to be considered to understand the ‘normal’ state of a volcano, but instead it is the set of geochemical, seismic, deformation, gravimetric indicators, and more that allows us to forecast the future behavior of the volcano,” says Pappalardo.

A dock in the port of Pozzuoli. The significant ground uplift from Campi Flegrei has caused the sea water to recede. March 2022.

KONTROLAB - Getty Images

Since 2012, and at the time of writing, the Campi Flegrei caldera has been at the yellow alert level, the second of four. “It is not currently believed on the basis of the trend of the monitored parameters that there is a risk of an impending eruption,” she continues.

As for Vesuvius, the volcano has calmed down since its last eruption in 1944, exhibiting only “low seismicity and fumarolic activity,” says Pappalardo, which is the emission of gasses such as sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide. Vesuvius is at a green level of alert, the first of four, and Pappalardo says there is no sufficient evidence to suggest it will erupt in the near future.

The Solfatara crater of Campi Flegrei.

Since 2012, and at the time of writing, the Campi Flegrei caldera has been at the yellow alert level, the second of four. “It is not currently believed on the basis of the trend of the monitored parameters that there is a risk of an impending eruption,” she continues.

As for Vesuvius, the volcano has calmed down since its last eruption in 1944, exhibiting only “low seismicity and fumarolic activity,” says Pappalardo, which is the emission of gasses such as sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide. Vesuvius is at a green level of alert, the first of four, and Pappalardo says there is no sufficient evidence to suggest it will erupt in the near future.

The Solfatara crater of Campi Flegrei.

KONTROLAB - Getty Images

Life Alongside a Volcano

In any case, Neapolitans continue about their lives as usual. Their houses, railway network, restaurants, schools, hospitals, and historical buildings are jammed between volcanoes, and there is no sign of residents wanting to abandon living even in the red zone. It’s not that people are unaware of the threat of a future eruption; they just worry about more immediate problems, such as unemployment and crime.

Many Neapolitans also don’t trust their public officials will ever successfully deliver comprehensive emergency plans for Phlegraean Fields or Vesuvius, and few are well-informed about their existence. Italian scientific experts have also admitted they don’t believe the civil authorities from all the municipalities involved will be able to follow through on the plans, as they neither study them nor care much to inform their towns about them.

In any case, Neapolitans continue about their lives as usual. Their houses, railway network, restaurants, schools, hospitals, and historical buildings are jammed between volcanoes, and there is no sign of residents wanting to abandon living even in the red zone. It’s not that people are unaware of the threat of a future eruption; they just worry about more immediate problems, such as unemployment and crime.

Many Neapolitans also don’t trust their public officials will ever successfully deliver comprehensive emergency plans for Phlegraean Fields or Vesuvius, and few are well-informed about their existence. Italian scientific experts have also admitted they don’t believe the civil authorities from all the municipalities involved will be able to follow through on the plans, as they neither study them nor care much to inform their towns about them.

A view of the Pisciarelli fumaroles, volcanic openings in the Earth’s surface, from the Agnano neighborhood of Naples, Italy, 2021. These fumaroles are located in the central area of Campi Flegrei and are one of its most active spots.

KONTROLAB - Getty Images

Volcanoes are not entirely a scourge for the areas in their periphery. They can also be a source of good: the ash and lava deposited around Naples by previous eruptions are rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium, which have made the soil fertile and provide a stable agricultural income for the local people. Neapolitans believe their volcanoes create a specific energy that gives the place its unique vibrancy–the “Neapolitan sound.”

Other Italians attribute personality traits to their volcanoes. They view them as capricious but alluring divas. Those living near Mount Etna, for example, call the volcano La Signora Etna. “Etna might be angry or calm,” Sicilians say; they hope “she” never gets angry. There is something about volcanoes only people who have grown up close to them seem to understand.

For a volcano such as Vesuvius—and its well-known counterparts Etna and Stromboli—its visibility and recent fury has almost bestowed upon it the status of a cultural icon. Campi Flegrei is different, though. It’s lying right under our feet—and waiting.

Volcanoes are not entirely a scourge for the areas in their periphery. They can also be a source of good: the ash and lava deposited around Naples by previous eruptions are rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium, which have made the soil fertile and provide a stable agricultural income for the local people. Neapolitans believe their volcanoes create a specific energy that gives the place its unique vibrancy–the “Neapolitan sound.”

Other Italians attribute personality traits to their volcanoes. They view them as capricious but alluring divas. Those living near Mount Etna, for example, call the volcano La Signora Etna. “Etna might be angry or calm,” Sicilians say; they hope “she” never gets angry. There is something about volcanoes only people who have grown up close to them seem to understand.

For a volcano such as Vesuvius—and its well-known counterparts Etna and Stromboli—its visibility and recent fury has almost bestowed upon it the status of a cultural icon. Campi Flegrei is different, though. It’s lying right under our feet—and waiting.

No comments:

Post a Comment