Dalia Faheid

Sat, January 7, 2023

Little Elm Councilman Tony Singh likes to joke that he’s an accidental politician. Growing up as a military brat with his father in the Indian Navy, 42-year-old Singh had become accustomed to packing his bags every few years.

“But now, Little Elm is my home forever,” Singh says.

With the goal of serving his newfound community, Singh signed up for Citizens Government Academy, an eight-week program offering Little Elm residents the opportunity to learn about the local government’s daily functions and roles. To help keep residents safe, the sales engineer and his wife Crystal volunteered with the police department, the fire department, Citizens on Patrol and Make 380 Safe. Before joining the town council, Singh served as a commissioner on the town’s planning and zoning commission.

“I thought elected officials should be more proactive, should be there for the community all the time, they should be accessible,” he said of his run for the town council. “People should be your first priority. I’m a volunteer first and a politician second.”

The growing number of Indian-Americans in North Texas is establishing itself as a formidable block in cities throughout the Metroplex. From technology, to schools to politics, Indian-Americans like Singh have made an indelible mark in the cultural fabric of North Texas.

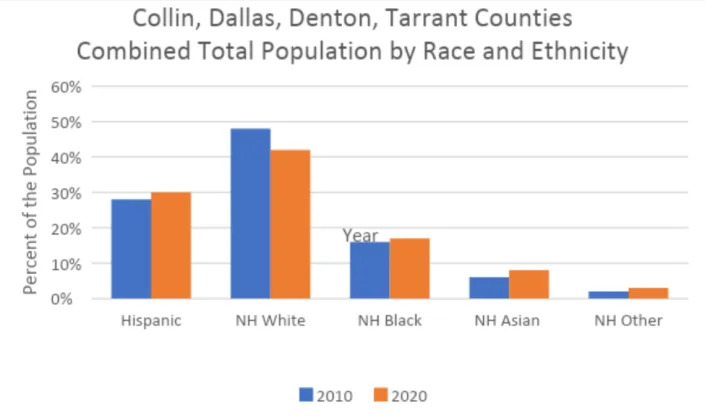

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2010 and 2020 5-year estimates

Asians are the state’s fastest-growing population, with Indian-Americans being the largest group in that category. Overall, Texas has the second largest Indian-American population in the country. In 2010, there were 230,842 Indian-Americans in Texas, making up 0.9% of the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2020, that number nearly doubled, with 434,221 Indian-Americans making up 1.5% of the state’s population.

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2010, 2015, 2020 5-year estimates

That growth was apparent in Dallas-Fort Worth, where about 220,000 Indian-Americans live. In Collin County, the Indian-American population grew from 3.8% to 7.5% in the last decade, and Denton County from 2.2% to 4.1%. The percentage of Indian-Americans in Dallas County went from 1.6% to 2.4%, and in Tarrant County it increased from 0.9% to 1.1%. Between 2015 and 2020 alone, about 14,189 more resided in Fort Worth, Dallas and Plano.

A career solving problems

McKinney resident Dinesh Hooda, 39, said he came to Texas in 2011 for the job opportunities. He had worked for cybersecurity company McAfee in India for nearly eight years before being transferred as a senior software engineer. Hooda earned a master’s degree in computer science in India, and later an MBA from Texas A&M University.

“Technology always fascinated me from the beginning when I was a child, because you can achieve more things by following the latest technology and it leads to more work,” he said. “Technology makes good use of human power and multiplies it a lot.”

Hooda is one of a large proportion of Indian-American science, technology, engineering, and mathematics workers in North Texas. More than half of Indian-American employees work in only three industries: computer science and mathematics, management and health care. They also own 5% of all businesses in Collin, Denton, Dallas and Tarrant counties, representing more than a third of all Asian businesses.

Indian-Americans are among the highest earners of all immigrants, according to an August report from the Indian American CEO Council and the Institute for Urban Policy Research at the University of Texas at Dallas. The average income for Indian-Americans in Dallas-Fort Worth is $58,879, about 48% more than other groups. And 41% make $150,000 or more annually, according to the Census Bureau. In North Texas, most Indian-Americans are college educated, with nearly half having a graduate or professional degree.

It was difficult for Hooda, his wife and four-year-old son to adjust to the change at first, not having the community he had in India. Even finding vegetarian food, which was usually easily accessible to them, had proved to be a challenge. And when school started, his son was anxious to go fearful that his teachers wouldn’t understand him.

“We did not know anyone here except my manager to whom I was reporting to,” he said. “When you don’t know anyone, then smaller things also become bigger things.”

That was until Hooda attended an Indian Independence Day event hosted by the India Association of North Texas. For the first time, Hooda’s family was able to connect with Indian Americans living in North Texas. Since then, that group has given them a sense of belonging and a tie to their Indian culture.

“It was really big for me, because I made a couple of friends from that group. And then that way, I felt that yeah there are more more people here in the area which look more like me. And then they also were going through the same immigration challenges in which I am going through,” Hooda said.

Hooda now works as senior technical program manager at Uber, where he works with engineers to prevent fraud on the platform.

“I want to definitely continue to work on challenging problems and solve them, and continue to grow in my career,” Hooda said.

A family’s promising future

Frisco resident Urmeet Juneja, 50, moved to the U.S. in 2012 to build a promising future for his family of four. Over the past decade, he and his wife Harleen raised their two kids Rajmeet and Manraj in North Texas, and that future has become a reality.

“Since I came from India to the U.S., it was kind of a little challenging to settle down. Not that much for me, but for my family and kids, because it was a change in culture, it was a change in language,” Juneja said. “So the kids took some time to get acclimatized with the culture and the language here. It was a couple of years before they actually felt settled down.”

Rajmeet and Manraj had to leave behind friends as well as extended family back in India, so Texas was initially a lonely place for them. Because English had not been their primary language, it took about a year of ESL classes before they felt fully comfortable communicating with classmates and teachers.

“What I could see is they would hang out with friends who were of the same culture and same background,” Juneja said. “It took them some time to get into the groove where they had friends who were non-immigrants.”

Soon, the family found a gurudwara, or Sikh temple, to worship at every Sunday. Later, Juneja became president of the India Association of North Texas. That community involvement helped the family remain connected to their values and culture and makes them feel at-home, Juneja said.

“We have a very large community,” Juneja said. “I myself am involved with the India Association of North Texas, so that’s kind of heavy involvement in the cultural activities and educational activities that the association does, plus we also deal with the state representatives, the mayor and all to take up the issues of the Indian community, if any, and then we also focus on growing the cultural diversity and showing that to the community at large. That keeps even the children connected with their culture, which is back in India.”

A senior at UTD, Rajmeet, 21, will be earning a computer science and engineering degree in 2023. As a Centennial High School senior, Manraj wants to attend the UT McCombs School of Business, majoring in business and finance. In the long-term, the 17-year-old plans to take up corporate law.

“That was the goal — that my kids would live in an environment where they’ll get a better education, they’ll get more prospects once they grow up,” he said. “I’m hoping my kids grow up and get into good jobs or start something of their own and do well in their life. And at the same time, also keeping intact their cultural values and being in touch with their Indian value system which we have grown up into.”

A significant political constituency

The more than 4.16 million Indian-Americans have appeared as a significant political constituency. In the United States, there are 1.9 million Indian-American voters.

Indian-Americans serve as elected officials throughout the Lone Star State, and even more are running for county, state and federal office this year. In the November election, advocacy group Indian American Impact endorsed six Texas candidates of South Asian descent. One of those running for re-election is Judge Juli Mathew, who in 2018 became the first Asian judge in Fort Bend County. Also, Euless resident Salman Bhojani would be the first South Asian elected to the Texas legislature.

“When I was running, there were very few [Indian-Americans] running, but now I see more and more people are running every year,” Councilman Singh said. “In coming years, Indian-Americans will be a very big group, which can influence a lot of things in this area, in all of Texas.”

Because of their relatively young status and recent arrival, the IACEO/UTD report says, it’s possible that the full political impact of the Indian-American community has not been fully realized. The Indian-American population is relatively young, with a median age of 40, compared to 46 for other immigrants. About two-thirds arrived in the U.S. after 2000. Dallas-Fort Worth approved the fourth highest number of green card holders from India, behind New York City, Chicago and San Francisco.

Groups like SAAVETX and the Indian American Coalition of Texas are helping to register South Asian voters in places of worship, community centers and neighborhoods throughout Texas. Those efforts helped to drive record turnout for the 2020 election. The biggest concern for the Indian-American community is the immigration system, Juneja says.

“I was fortunate enough to come on an L-1A visa, which is the executive visa, but most of the Indian American community comes on the H-1B visa and then they struggle to keep the status intact. A lot of times their kids they grew up for like 14, 15 years, they stay on H-1B, and the kids after the age of 21 they are out of status and they have to struggle to find their own immigration status,” Juneja said. “We have the people who have been staying here from such a long time. But then also we have an influx of new people coming in every year on an H-1B visa, those who have been here for 10 years and still struggling to get a permanent status.”

In 2003, Singh moved to Texas from India to get his master’s degree in electrical engineering at the University of Texas at Arlington. Then in 2011, he decided to settle in Little Elm with Crystal because it had the unique charm of a small town, like the beach on the shores of Lake Lewisville, with all the amenities of a big city, including health care that Crystal needed as a cancer survivor.

Now in his second term, Singh still does regular volunteer work, like helping out at the Little Elm Area Food Bank every first Saturday of the month and making donations through his nonprofit called the Little Elm Angels Foundation. He aims to get more residents informed of what is happening with their town and get more involved.

“As long as I can take care of the people, respond to people on-time, be accessible to people and create value for the town, we’ll be here,” Singh said.

No comments:

Post a Comment