R.J. RICO

Sun, January 29, 2023

ATLANTA (AP) — Tortuguita’s cautious voice rang out from a platform amid the tall pines the first time Vienna met them: “Who goes there?” she remembers them calling.

The tree-dweller, who chose the moniker Tortuguita – Spanish for “Little Turtle” – over their given name, was perched above the forest floor in the woods just outside Atlanta last summer.

Vienna quickly identified herself, and Tortuguita’s watchfulness melted into the bubbly, curious, funny persona so many in the forest knew. They welcomed the newcomer and helped her settle in alongside the other self-proclaimed “forest defenders” on an 85-acre (34-hectare) site officials plan to develop into a huge police and firefighter training center. Protesters derisively call it “Cop City.”

“It was a magical experience for me, being able to live out our ideals,” Vienna told The Associated Press, recalling how the protesters shared clothing, food and money, all while engaging in community activism. She and Tortuguita quickly fell in love during those warm, late summer days.

That was before. Before a Jan. 18 police operation that ended in gunfire, leaving 26-year-old Tortuguita dead and a state trooper hospitalized, shot in the abdomen. Officials have said officers fired in self-defense after Tortuguita, whose given name was Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, shot the trooper. Activists argue it was state-sanctioned murder.

Outrage over the events has galvanized leftists around the world, with vigils from Seattle to Chicago to London to Lützerath, Germany.

Environmentalists for years had urged officials to turn the land into park space, arguing that the tall, straight pines and oaks were vital to preserving Atlanta’s tree canopy and minimizing flooding.

Vienna, 25, recalls her first four months there as joy-filled. There were campfires and sleepovers, in her tent or Tortuguita’s, nestled in the large wooded tract that activists call the Weelaunee Forest, the Muscogee (Creek) name for the land.

City Council approved the $90 million Atlanta Public Safety Training Center in 2021, saying a state-of-the-art campus would replace substandard offerings and boost police morale beset by hiring and retention struggles in the wake of violent protests against racial injustice that roiled the city after George Floyd’s death in 2020.

The planned development, largely financed by private corporate donations, enraged activists. Trees would be razed to build a shooting range, a “mock village” to rehearse raids and a driving course to practice chases. All would be within earshot of a poor, majority-Black neighborhood in a city with one of the nation’s highest degrees of wealth inequality.

Like many of those who took to living in the forest to oppose the development, Tortuguita was an eco-anarchist committed to fighting climate change and halting expansion of a police state, Vienna said.

Beyond the distrust many in the “Stop Cop City” movement have toward police, six people who knew Tortuguita told the AP that authorities’ allegations about the protester's final encounter do not match up with the person they knew: someone who, almost to a fault, always put others first.

“They were genuinely so generous and loving and always wanted to take care of people,” Vienna said of her partner, who last year took a 20-hour course to become a medic for the activists. “Their biggest thing was building communities of care.”

Tortuguita’s brother, Daniel Esteban Paez, said his sibling was even growing long hair to donate to children with cancer.

Tortuguita was a “citizen of Earth,” Paez said, growing up in their home country of Venezuela as well as Aruba, London, Russia, Egypt, Panama and the U.S. as their stepfather’s oil industry career led the family around the world. Tortuguita graduated magna cum laude from Florida State University and had been active in Food Not Bombs, helping feed homeless people in Tallahassee, Florida.

They had lived for several months among the “Stop Cop City” campers, a group whose reputation had been growing among leftist activists.

The campers built platforms in the trees and slept out, seeking public support and to block construction. They barricaded forest entrances and have been accused of threatening contractors and vandalizing heavy equipment.

Officials recently ratcheted up pressure. In December, authorities said firefighters and police officers were removing barricades to the site when they were attacked with rocks and incendiary devices. Vienna was among six arrested and accused of domestic terrorism for allegedly throwing rocks at fire department and emergency services workers, as well as a moving police vehicle. She’s fighting the charges in court.

The allegations are designed to scare others away from the cause, argued Marlon Kautz of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, a group providing legal aid to those arrested.

“These charges are purely being brought for the sake of putting activists in jail ... and demonizing the movement in the public eye,” Kautz said. “When we see the authorities using the criminal justice system to chill speech and prevent activists from associating with the movement, that is a grave threat to democracy.”

DeKalb County District Attorney Sherry Boston declined to comment on the specific facts of each case but said "if a person uses threats and violence in an effort to force a government entity to change a policy ... that is defined as Domestic Terrorism according to the Georgia statute.”

A month after the December altercation with police, Tortuguita was dead, killed as officers tried to clear remaining protesters from the site. Seven others were arrested on domestic terrorism charges during what authorities called a “clearing operation.”

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation has said there is no body camera or dashcam footage of the shooting, but that ballistic analysis shows the trooper was shot by a bullet from a handgun in Tortuguita’s possession.

The GBI said Tortuguita was inside a tent and did not comply with officers’ commands prior to firing at authorities. Vienna declined to comment when asked whether she knew if her partner had a gun, though the GBI says records show Tortuguita legally purchased the firearm in 2020.

Vienna and other activists have questioned the official version of events, calling the shooting a “murder,” accusing officials of an inconsistent, vague narrative and demanding an independent investigation. The GBI says it has a “track record of impartiality” when investigating officer-involved shootings.

On Saturday, violence and vandalism broke out when a masked contingent among hundreds protesting in downtown Atlanta began throwing rocks and aiming fireworks at a skyscraper housing the Atlanta Police Foundation. Activists then lit a police cruiser on fire and smashed a few more windows. No injuries were reported.

Authorities arrested six more people that night on charges including domestic terrorism, saying that “explosives” had been recovered. Police declined to elaborate when asked whether they were referring to fireworks or more dangerous incendiary devices.

“Make no mistake about it: these individuals meant harm to people,” Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens said during a news conference Saturday.

In response, GOP Gov. Brian Kemp on Thursday declared a state of emergency, giving him the option of calling in the Georgia National Guard to help “subdue riot and unlawful assembly.”

Paez, Tortuguita’s 31-year-old brother from Texas, said his family is heartbroken.

“Our family doesn’t want violence toward cops, but we also don’t want violence from cops,” Paez told the AP. “I’m just terrified at the thought that the tactics that were used to kill my sibling are going to be replicated at Cop City.”

He bristles at the allegation that Tortuguita was a domestic terrorist. They were too kind. Too smart. Too caring.

“He was a privileged person but he chose to be with the homeless, to be with the people that needed his caring,” said Tortuguita’s mother, Belkis Terán, who lives in Panama.

For a long time, Paez said he did not care about the forest’s fate. He was far more concerned about Tortuguita’s safety.

“I told my sibling, ‘If you were ever to die, I’m going to dump oil and hazardous materials in your stupid forest,’” Paez recalled, his voice cracking. “They called my bluff. I care about the forest now.”

Arrests in Atlanta 'Cop City' protests raise concerns over domestic terrorism charges

Daniella Silva

Sun, January 29, 2023

The decision by prosecutors to pursue domestic terrorism charges against opponents of a police training center outside Atlanta is drawing criticism, with some legal experts saying it’s a potentially dangerous overreach that could be viewed as politically motivated.

More than a dozen people have been charged with domestic terrorism in connection with the protests, including seven people after a Jan. 18 confrontation with police who were trying to clear the proposed site of the center, dubbed "Cop City" by critics.

One man was fatally shot by police in the confrontation after he opened fire and wounded a state trooper, authorities said. In protests that followed the killing and the police sweeps, six people were arrested and charged with domestic terrorism.

In December, the same charges were filed against five people after law enforcement moved in to clear barricades and confront protesters.

Critics of domestic terrorism laws, including some civil rights groups, oppose them “because of the risk of politicization, because they can be used against politically disfavored groups by the government,” Patrick Keenan, a professor of law at the University of Illinois, said.

A 2017 Georgia law defines domestic terrorism as a felony intended to kill or harm people; “disable or destroy critical infrastructure, a state or government facility, or a public transportation system"; “intimidate the civil population or any of its political subdivisions”; and change or coerce state policy or affect the conduct of government “by use of destructive devices, assassination, or kidnapping.” Conviction carries a maximum sentence of 35 years in prison.

The allegations against the protesters include trespassing, resisting arrest, throwing rocks and glass bottles and damaging property, including setting fire to a police car. Authorities have also said they found “explosive devices, gasoline, and road flares” in an area in the forest where protesters had makeshift treehouses.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, has called the protesters “militant activists” and said “we will bring the full force of state and local law enforcement down on those trying to bring about a radical agenda through violent means.”

Sun, January 29, 2023

ATLANTA (AP) — Tortuguita’s cautious voice rang out from a platform amid the tall pines the first time Vienna met them: “Who goes there?” she remembers them calling.

The tree-dweller, who chose the moniker Tortuguita – Spanish for “Little Turtle” – over their given name, was perched above the forest floor in the woods just outside Atlanta last summer.

Vienna quickly identified herself, and Tortuguita’s watchfulness melted into the bubbly, curious, funny persona so many in the forest knew. They welcomed the newcomer and helped her settle in alongside the other self-proclaimed “forest defenders” on an 85-acre (34-hectare) site officials plan to develop into a huge police and firefighter training center. Protesters derisively call it “Cop City.”

“It was a magical experience for me, being able to live out our ideals,” Vienna told The Associated Press, recalling how the protesters shared clothing, food and money, all while engaging in community activism. She and Tortuguita quickly fell in love during those warm, late summer days.

That was before. Before a Jan. 18 police operation that ended in gunfire, leaving 26-year-old Tortuguita dead and a state trooper hospitalized, shot in the abdomen. Officials have said officers fired in self-defense after Tortuguita, whose given name was Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, shot the trooper. Activists argue it was state-sanctioned murder.

Outrage over the events has galvanized leftists around the world, with vigils from Seattle to Chicago to London to Lützerath, Germany.

Environmentalists for years had urged officials to turn the land into park space, arguing that the tall, straight pines and oaks were vital to preserving Atlanta’s tree canopy and minimizing flooding.

Vienna, 25, recalls her first four months there as joy-filled. There were campfires and sleepovers, in her tent or Tortuguita’s, nestled in the large wooded tract that activists call the Weelaunee Forest, the Muscogee (Creek) name for the land.

City Council approved the $90 million Atlanta Public Safety Training Center in 2021, saying a state-of-the-art campus would replace substandard offerings and boost police morale beset by hiring and retention struggles in the wake of violent protests against racial injustice that roiled the city after George Floyd’s death in 2020.

The planned development, largely financed by private corporate donations, enraged activists. Trees would be razed to build a shooting range, a “mock village” to rehearse raids and a driving course to practice chases. All would be within earshot of a poor, majority-Black neighborhood in a city with one of the nation’s highest degrees of wealth inequality.

Like many of those who took to living in the forest to oppose the development, Tortuguita was an eco-anarchist committed to fighting climate change and halting expansion of a police state, Vienna said.

Beyond the distrust many in the “Stop Cop City” movement have toward police, six people who knew Tortuguita told the AP that authorities’ allegations about the protester's final encounter do not match up with the person they knew: someone who, almost to a fault, always put others first.

“They were genuinely so generous and loving and always wanted to take care of people,” Vienna said of her partner, who last year took a 20-hour course to become a medic for the activists. “Their biggest thing was building communities of care.”

Tortuguita’s brother, Daniel Esteban Paez, said his sibling was even growing long hair to donate to children with cancer.

Tortuguita was a “citizen of Earth,” Paez said, growing up in their home country of Venezuela as well as Aruba, London, Russia, Egypt, Panama and the U.S. as their stepfather’s oil industry career led the family around the world. Tortuguita graduated magna cum laude from Florida State University and had been active in Food Not Bombs, helping feed homeless people in Tallahassee, Florida.

They had lived for several months among the “Stop Cop City” campers, a group whose reputation had been growing among leftist activists.

The campers built platforms in the trees and slept out, seeking public support and to block construction. They barricaded forest entrances and have been accused of threatening contractors and vandalizing heavy equipment.

Officials recently ratcheted up pressure. In December, authorities said firefighters and police officers were removing barricades to the site when they were attacked with rocks and incendiary devices. Vienna was among six arrested and accused of domestic terrorism for allegedly throwing rocks at fire department and emergency services workers, as well as a moving police vehicle. She’s fighting the charges in court.

The allegations are designed to scare others away from the cause, argued Marlon Kautz of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, a group providing legal aid to those arrested.

“These charges are purely being brought for the sake of putting activists in jail ... and demonizing the movement in the public eye,” Kautz said. “When we see the authorities using the criminal justice system to chill speech and prevent activists from associating with the movement, that is a grave threat to democracy.”

DeKalb County District Attorney Sherry Boston declined to comment on the specific facts of each case but said "if a person uses threats and violence in an effort to force a government entity to change a policy ... that is defined as Domestic Terrorism according to the Georgia statute.”

A month after the December altercation with police, Tortuguita was dead, killed as officers tried to clear remaining protesters from the site. Seven others were arrested on domestic terrorism charges during what authorities called a “clearing operation.”

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation has said there is no body camera or dashcam footage of the shooting, but that ballistic analysis shows the trooper was shot by a bullet from a handgun in Tortuguita’s possession.

The GBI said Tortuguita was inside a tent and did not comply with officers’ commands prior to firing at authorities. Vienna declined to comment when asked whether she knew if her partner had a gun, though the GBI says records show Tortuguita legally purchased the firearm in 2020.

Vienna and other activists have questioned the official version of events, calling the shooting a “murder,” accusing officials of an inconsistent, vague narrative and demanding an independent investigation. The GBI says it has a “track record of impartiality” when investigating officer-involved shootings.

On Saturday, violence and vandalism broke out when a masked contingent among hundreds protesting in downtown Atlanta began throwing rocks and aiming fireworks at a skyscraper housing the Atlanta Police Foundation. Activists then lit a police cruiser on fire and smashed a few more windows. No injuries were reported.

Authorities arrested six more people that night on charges including domestic terrorism, saying that “explosives” had been recovered. Police declined to elaborate when asked whether they were referring to fireworks or more dangerous incendiary devices.

“Make no mistake about it: these individuals meant harm to people,” Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens said during a news conference Saturday.

In response, GOP Gov. Brian Kemp on Thursday declared a state of emergency, giving him the option of calling in the Georgia National Guard to help “subdue riot and unlawful assembly.”

Paez, Tortuguita’s 31-year-old brother from Texas, said his family is heartbroken.

“Our family doesn’t want violence toward cops, but we also don’t want violence from cops,” Paez told the AP. “I’m just terrified at the thought that the tactics that were used to kill my sibling are going to be replicated at Cop City.”

He bristles at the allegation that Tortuguita was a domestic terrorist. They were too kind. Too smart. Too caring.

“He was a privileged person but he chose to be with the homeless, to be with the people that needed his caring,” said Tortuguita’s mother, Belkis Terán, who lives in Panama.

For a long time, Paez said he did not care about the forest’s fate. He was far more concerned about Tortuguita’s safety.

“I told my sibling, ‘If you were ever to die, I’m going to dump oil and hazardous materials in your stupid forest,’” Paez recalled, his voice cracking. “They called my bluff. I care about the forest now.”

THE FBI DECLARED ECO ACTIVISTS TERRORISTS AFTER 9/11

NO ECO ACTIVISTS WERE SAUDI'S

Daniella Silva

Sun, January 29, 2023

The decision by prosecutors to pursue domestic terrorism charges against opponents of a police training center outside Atlanta is drawing criticism, with some legal experts saying it’s a potentially dangerous overreach that could be viewed as politically motivated.

More than a dozen people have been charged with domestic terrorism in connection with the protests, including seven people after a Jan. 18 confrontation with police who were trying to clear the proposed site of the center, dubbed "Cop City" by critics.

One man was fatally shot by police in the confrontation after he opened fire and wounded a state trooper, authorities said. In protests that followed the killing and the police sweeps, six people were arrested and charged with domestic terrorism.

In December, the same charges were filed against five people after law enforcement moved in to clear barricades and confront protesters.

Critics of domestic terrorism laws, including some civil rights groups, oppose them “because of the risk of politicization, because they can be used against politically disfavored groups by the government,” Patrick Keenan, a professor of law at the University of Illinois, said.

A 2017 Georgia law defines domestic terrorism as a felony intended to kill or harm people; “disable or destroy critical infrastructure, a state or government facility, or a public transportation system"; “intimidate the civil population or any of its political subdivisions”; and change or coerce state policy or affect the conduct of government “by use of destructive devices, assassination, or kidnapping.” Conviction carries a maximum sentence of 35 years in prison.

The allegations against the protesters include trespassing, resisting arrest, throwing rocks and glass bottles and damaging property, including setting fire to a police car. Authorities have also said they found “explosive devices, gasoline, and road flares” in an area in the forest where protesters had makeshift treehouses.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, has called the protesters “militant activists” and said “we will bring the full force of state and local law enforcement down on those trying to bring about a radical agenda through violent means.”

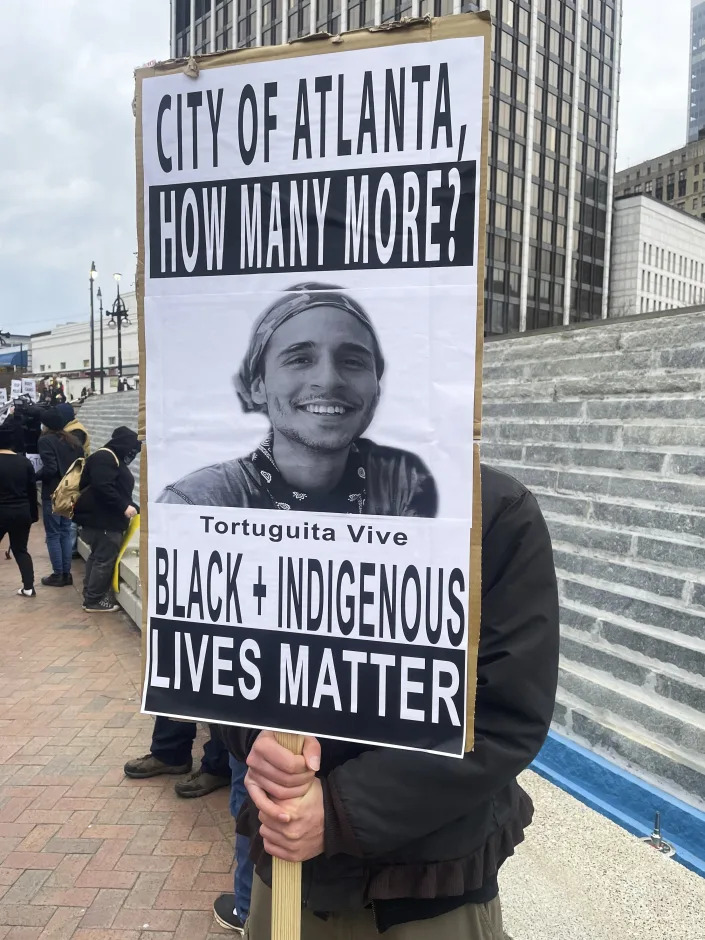

A protester holds up a sign that says

Although “domestic terrorism” is defined in the Patriot Act of 2001, there is no specific federal crime covering acts of terrorism inside the U.S. that are not connected to al Qaeda, the Islamic State, other officially designated international terrorism groups or their sympathizers — even though the U.S. has said in recent years that white supremacist and militia groups are a top domestic terrorism threat.

Last year's mass shooting at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, fit that category, said Javed Ali, an associate professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.

The 19-year-old white supremacist who shot and killed 10 Black people last May was the first person in New York state convicted of domestic terrorism motivated by hate; he also pleaded guilty to first-degree murder. The terrorism charge carries an automatic sentence of life in prison.

But in a number of states, including Georgia, domestic terrorism laws include a wide range of offenses outside those motivated by hate.

Because the Georgia statute “focuses on conduct that is intended to intimidate the government or to affect the government in any way,” Keenan, the law professor, said, it is “especially vulnerable to politicized use.”

Keenan said he believes attaching the domestic terrorism label to protesters could have “some really dangerous effects.”

“I don’t think it’s mostly protesters who are the biggest domestic terrorism threats. Domestic terrorism threats are coming from other places, and so to use this statute really publicly and prominently to try to squash this protest seems to me, kind of the politicized use of the law that a lot of people were worried about,” he said.

Keenan said that while he does not condone violence or attacks on law enforcement, he believes there are other ways to address those things under Georgia law that do not include a domestic terrorism charge.

“As someone who handled capital murder cases in Georgia, I can tell you Georgia law has a lot of ways to deal with violence against law enforcement or against anyone,” he said. “So this domestic terrorism statute is not necessary and it can lead to this politicized use that I think doesn’t do anybody any good.”

Joshua Schiffer, an attorney who represents one of the protesters, said he believes that as the investigation moves forward, “the charges won’t be justified,” calling them “particularly concerning” given Georgia’s rich history of civil rights and civil disobedience.

“The use by the state of such an aggressive statute indicates the state’s position when it comes to protesters and how the state intends to deal with protesters,” he said. “This state action is meant to impact and chill this protest issue nationally.”

Ali, a former senior U.S. government counterterrorism official, said such cases highlight what could be a new development at the state and local level where authorities will begin to bring more domestic terrorism charges.

He said that prosecutors typically bring such charges when they believe there is enough evidence to support them, “because why would you bring a charge forward on something that’s fairly unusual and controversial if you’re going to lose the case in court?”

In the months leading up to the most recent arrests, critics have raised environmental concerns about building a $90 million law enforcement training center on 85 acres just outside Atlanta. Opponents say it would devastate forest, and they also object to making such a huge investment in policing after the national 2020 protests against police violence and systemic racism following the murder of George Floyd.

Officials have defended the center, saying that the forested land was the only viable location and law enforcement needs modern training facilities.

On Thursday, Kemp declared a state of emergency in Georgia, the result, he said, of “unlawful assemblage, violence, overt threats of violence, disruption of peace and tranquility of this state and danger existing to persons and property.” The order gives Kemp the ability to call in the Georgia National Guard.

Marlon Kautz, an activist with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which provides resources to people arrested during protests, said the group was “extremely alarmed at the use of this domestic terrorism statute.”

“It’s clear that it’s being used in an overly broad way to maliciously prosecute people,” he said.

The Atlanta Solidarity Fund said that the state of Georgia was trying to “set an alarming precedent” with the charges.

“If they are successful, protesters across the country could be facing similar speech-chilling ‘domestic terrorism’ charges,'” it said in a statement this week. “We must strongly reject this extreme level of repression here and now, before it becomes the norm for activists in every movement.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

A police officer blocks a downtown street following a protest, Saturday, Jan. 21, 2023, in Atlanta, in the wake of the death of an environmental activist killed after authorities said the 26-year-old shot a state trooper. (AP Photo/Alex Slitz)

No comments:

Post a Comment