Christian climate activist challenges church to take action

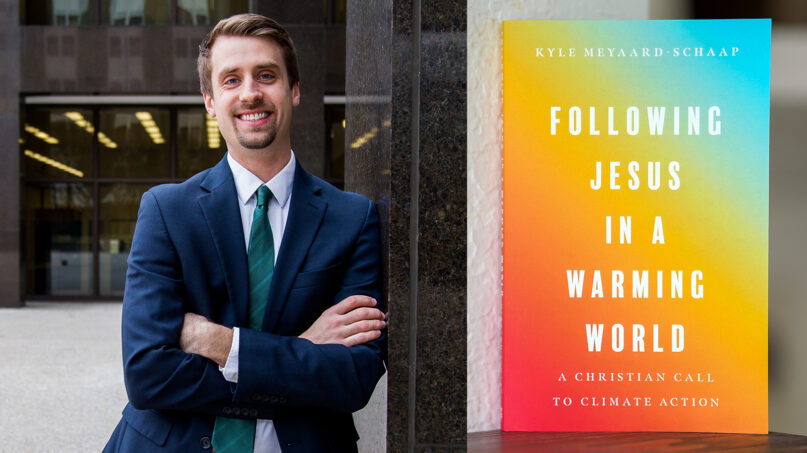

Kyle Meyaard-Schaap's 'Following Jesus in a Warming World' is a field guide for Christian climate action.

(RNS) — When Kyle Meyaard-Schaap was 17, his brother came home from a semester abroad and announced the unthinkable: He was a vegetarian.

“It was as if he announced to the family that he was a dog now,” Meyaard-Schaap told Religion News Service. “I didn’t know anybody who had ever made that choice.”

At the time, a meatless diet didn’t fit into the definition of Christianity he’d learned in his conservative religious community.

“(My brother) helped me understand that him making that choice wasn’t him rejecting all of the beautiful values that we had been taught in our Christian community,” said Meyaard-Schaap. “It was him trying to live more deeply into those values. It was the first time someone had given me permission to consider things like climate change, pollution, environmental degradation through the lens of my faith.”

Years later, Meyaard-Schaap is now the vice president of the Evangelical Environmental Network, a group that advocates for climate action because of, not in spite of, their faith. His new book, “Following Jesus in a Warming World: A Christian Call to Climate Action,” offers personal accounts, theological frameworks and practical advice for Christian climate action.

RNS spoke to Meyaard-Schaap about his book, releasing from InterVarsity Press on Feb. 21. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did your trip to West Virginia complicate your perspective on the climate crisis?

That trip helped me see that creation care equals people care. I think before that, it was easy for me to hide behind the numbers and statistics. I was pretty strident in my convictions around the need to dump fossil fuels immediately and get on a path to clean energy as fast as possible. And I still believe that’s vitally important.

But during my trip to West Virginia, I met people who were shining with pride at how they had kept the lights on in America for decades. They were proud to work in the coal mines. And then on the other hand, many of them were dying from black lung disease or had granddaughters who had pediatric cancer because of the heavy metals that have leached into the drinking water from the contamination from the mine sites. It helped me understand that fossil fuels have done a lot of good for our country, and they brought a ton of people out of poverty. And at the same time, it’s had profoundly damaging consequences on our air, our water, our climate.

It helped me understand that if we’re going to address this with compassion, and in a way that actually does put people first, we have to wrestle with this idea that livelihoods and people are wrapped up in the current status quo. And we need to transition away from fossil fuels immediately, but we have to do it in a way that doesn’t leave these people behind.

Young Evangelicals for Climate Action demonstrate in Washington, D.C., in 2017. Courtesy photo

What does Jesus’ incarnation have to do with climate justice?

In Jesus, we have the infinite Creator God choosing to take on the stuff of that creation, and to bind himself to it forever. I can’t think of a greater affirmation of the goodness of created things. It’s such a powerful counter narrative to some of the more Gnostic, dualistic theologies that many of us who grew up in the American church in the ’80s, ’90s and early aughts breathed in — the rapture, “Left Behind” theology that says that our souls are what matter, and the body has nothing of eternal importance.

I think the incarnation and the resurrection fly in the face of that and affirm the inherent dignity of humanity and of all created things. It helps us recover a more radically integrated theology that understands body and the soul as inseparable.

What’s your response to Christians who argue that humans were called to have dominion over creation?

I would say yes, but it’s incomplete. Yes, Genesis (chapter) 1 says, God creates humans in his image and tells him to rule over the fish in the sea, the birds in the air and everything that moves along the ground. And I wish that Hebrew word for rule, “radah,” was softer, but it’s harsh.

“Following Jesus in a Warming World: A Christian Call to Climate Action” by Kyle Meyaard-Schaap. Courtesy image

But I think the error is separating Genesis 1 from Genesis 2. In Genesis (chapter) 2, God takes the man that he creates from the dust of the ground, breathes his breath into him and says “avad and shamar” this garden, which is translated as “serve and protect.” I think these two commands become a couplet of instructions. So Genesis 1 and 2 tell us to rule by serving and protecting.

The rest of Scripture is clear that creation has one king, and it’s Christ. If we’re going to rule alongside Christ, we have to look at how Christ exercises his authority. He becomes a baby. He washes feet. He climbs up on a cross. Christ exercises his authority through humility, service and sacrifice, not through exploitation and domination. So rule, yes, but rule through service and by protecting the vulnerable.

Why did you include a chapter on being pro-life in this book?

I think many of us, particularly in America, are suffering from a myopic idea of what it means to be pro-life in the modern world. So many of us associate it simply with the issue of abortion. If we truly want to honor life as the gift that it is from God, let’s think about things like climate change, pollution and the spread of disease, which is made worse by climate change.

If we’re going to be serious about protecting and defending life in all of its fullness, we have to be concerned about not just abortion, but young kids, adults, the poor, people of color, the elderly, the disabled. And we have to think about how other issues like climate change affect people’s ability to access that abundant life that Jesus said he came to give right here and now.

Kyle Meyaard-Schaap. Courtesy photo

What advice would you give to people who are wrestling with the ethics of bringing new life into this world?

So many people in our generation are really grappling with that. I want to honor that and say, good for you for realizing we need to think about these giant issues that will affect our children. On the other hand, I find it hard to believe there’s ever been a generation that hasn’t felt existential dread. Our parents and grandparents were living under the specter of nuclear holocaust.

Ultimately, where my wife and I land is that our trust in God’s good plans for the world has always been stronger than our fear of what could happen. But I think with that trust also comes responsibility. So we are raising our boys to understand the consequences of human greed and selfishness that have led to the degradation of the world they are inheriting. And we’re trying to raise them in a way that lives more lightly on the earth and incorporates advocacy for policies that can change that. I don’t think it’s morally defensible right now to choose to have children and then go to sleep to the realities of climate change and the future our kids are facing.

Who did you write this book for, and what do you hope they take away from it?

I wanted this book to be accessible to anybody who’s a believer or is interested in how believers talk about this. When I sat down and I had a person in mind, it was for a millennial or a Gen Z Christian who grew up in the American church who was concerned about climate change but doesn’t think their church cares about it. I want those people to come away from this book encouraged. I want them to feel seen and to go away empowered with actual tools to integrate this more deeply into their life of faith. So if a young Christian is standing on the edge of climate despair and thinking the church doesn’t care, I want this book to pull them back and say, you’re not alone. Millions of other Christians like you understand this. We’re concerned, too. And we want to do something about it. So let’s get to work.

No comments:

Post a Comment