A startup named Machina Labs is using robots to make the kinds of metal components for manufacturers that have often required significant manual work in the past.

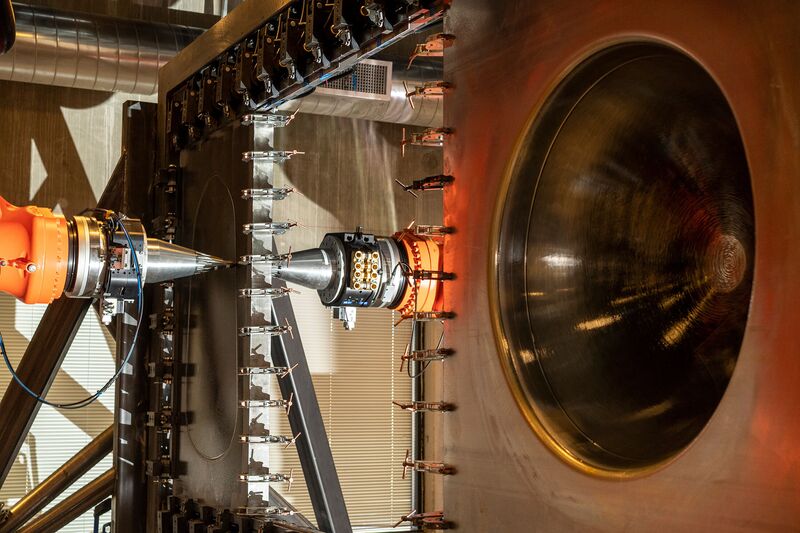

A robot forms metal sheets at Machina Labs in Chatsworth, California.

By Ashlee Vance

February 21, 2023

A few months ago, I stood in front of a laser scanner that made a digitized file of my head. Using that file as a guide, two gigantic robot arms set to work poking and prodding at a piece of sheet metal until they had replicated every contour of my face in fine detail. While the robots looked large and clumsy, they were able to perform the same type of precision metal shaping that has been done for centuries by skilled craftspeople. In the end, they manufactured a realistic bust I could be proud of, my own genetic limitations notwithstanding.

The bust was the work of Machina Labs, the Chatsworth, California-based startup that made the metalworking system. The company’s ambitions go far beyond doing cute things like reproducing reporters’ faces. Its primary focus is on saving industrial companies time and money by putting a robotic blacksmithing army at their disposal. “I never thought we’d see anything like this,” says Bobby Walden, the owner of Walden Speed Shop, who has spent decades hand-making custom metal parts for cars. Walden has visited the Machina factory and reckons the robots are already good enough to replicate much of what he does, only without the arthritis and back pain. “I’m looking at this robot, and my brain starts going crazy,” he says.

The robots at Machina have single arms that can wield a variety of tools.

Machina founders Edward Mehr and Babak Raeisinia have metalworking experience, both as hobbyists and through careers spent at companies including Space Exploration Technologies Corp. and the aluminum recycler Novelis Inc. They started their current business, which has never publicly discussed its technology in detail, four years ago. The idea was to blend software, sensors and metalworking tools into a system that could make all kinds of metal parts in a matter of hours, serving industries struggling to get parts quickly because of a dearth of skilled craftspeople. Machina has raised $22 million from investors including Innovation Endeavors and Lockheed Martin and counts NASA, the US Air Force and hypersonic airplane startup Hermeus among its customers.

Typically, a maker of planes or cars will spend many millions of dollars and several years creating the molds needed to stamp out metal parts by the thousands. This process often requires multiple prototype molds, each requiring significant investment and time to produce. Machina’s robots are still too slow to replace the mass production portion of this equation. But they’re ideal for the earlier stages of the process, helping companies test their ideas before they commit money to final production.

Machina co-founder and CEO Edward Mehr.

Another source of business is companies that need to make a few dozen or a few hundred metal parts—be it for replacement equipment or custom manufacturing—and don’t have the capital to invest in making molds. “I’ve got this line of car brakes, and getting them into production has been a huge pain in the ass,” says Walden, who is not a Machina customer. “It can take a year to get one prototype. Then I have one-off parts, and they can cost $60,000 to $200,000 for the dies and molds. With the robot, I can get the same thing in a couple of weeks and for way less money.”

Iranian-born Mehr, 36, is the company’s chief executive officer. After getting a degree in computer science from the University of Southern California, he worked at rocket makers SpaceX and Relativity Space Inc. and watched them struggle with manufacturing. Both companies were using advanced 3D-printing techniques for some of their most complex hardware, but other parts of manufacturing remained too costly and time-consuming. “I love 3D printing, but the concept here is around having more overarching automation,” Mehr says. “We want to automate things like forging and metal shaping.”

The robots that Machina uses, which have single arms that can wield various tools, are already found on the assembly lines of carmakers and other manufacturers. The company positions two robots on either side of a large sheet of metal. One of them provides support on the back of the metal sheet, while the other applies pressure and twists and turns to form the metal into shapes.

Robotically formed metal shapes at Machina’s facility in Chatsworth.

It takes master craftspeople years to learn how to create strong, polished final products from metal sheets. The difficulty is largely a result of the way atoms inside the metal move around as the material is shaped, causing bulges and other deformations to appear in odd places. Machina’s technology feeds the properties of metal into computer vision and artificial intelligence systems that monitor the shaping process as the robots go to work. Such techniques have been the subject of academic research for decades; Machina has distinguished itself through its ability to refine and commercialize the technology.

It’s still early days for the company, whose offerings start at $2.5 million for two robots, a metal fixture to hold the metal sheets in place, and tools. Mehr and his team also spend a lot of time with customers making sure they’re using the machines right and dealing with any problems that arise.

Workers at Machina make adjustments to a robot before it works on a piece of sheet metal.

One customer is Robins Air Force Base in Houston County, Georgia, which has ordered Machina robots to help with the repair of such aircraft as the C-17 Globemaster transport plane and F-15 Eagle fighter jet. Shane Groves, who specializes in robotics and automation for air logistics at the base, has done testing on parts made with the Machina machines. He found that they’re shaped better than what humans can do and that the parts are stronger as a result of the techniques Machina uses to form them.

Groves also says he’s drawn to Machina simply because it can get things done faster. “The main problem we have right now is that companies have plenty of work, and when I ask them for one or two parts, they don’t see the return in tooling everything up for a small order,” he says. “We’re getting quotes for four-year delivery times to get some of the right parts.”

Photographer: Kyle Grillot/Bloomberg

No comments:

Post a Comment