The life of a dog

Born into a cosmopolitan Jewish family, Ferenc Fejtő lived a turbulent youth as a Marxist and social democrat in Horthy’s Hungary. Having fled just before the fascist rise to power, he led a more comfortable life as a journalist and historian of eastern Europe in Paris, remaining within the left even after his disillusionment with communism.

An anti-communist is a dog. You won’t budge me on that. I won’t ever be budged on that.

Jean-Paul Sartre

LONG READ

Interviewed in 1984 by a Hungarian television crew which had come to visit him in his Parisian exile, the veteran journalist and historian François Fejtő declared: ‘… indeed I could boast of being a great testament to stability. I’ve been living in the same house for the last forty years, with the same telephone number. In fifty years I haven’t changed wife, or my political opinions.’

While these statements seemed on the face of it to be factual, one imagines they may have been delivered with something of a twinkle. For if Fejtő’s final six decades – he died aged ninety-eight in 2008 – were largely spent in quiet intellectual work and attended by stability and a measure of bourgeois comfort, his earlier life had been a great deal more various and turbulent.

Fejtő is probably not much remembered today, at least in English-speaking countries, where his works – those of them that were translated in the first place – seem to be out of print, but his two-volume history of the postwar ‘people’s democracies’ of central and eastern Europe, translated from its original French into a dozen or more languages and published in English by Penguin, was for a long time a standard work.

His many other books, normally first published in Paris, included accounts of the ‘Prague coup’ (communist seizure of power) of 1948, the 1956 Hungarian revolution, the Prague Spring of 1968 with its promise of ‘socialism with a human face’ and the Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960s; biographies of the Habsburg emperor Joseph II and the German poet Heinrich Heine; historical studies of the revolutions of 1848 and of the post-WWI dissolution, or as Fejtő sees it, ‘destruction’ of the Austro-Hungarian empire; a study of Leninism and its political heritage, reflections on the various forms of European social democracy in the mid-twentieth century and on religious belief (Christian and Jewish) and its bearing on ‘the problem of evil’; there were also, late in his life, a number of volumes of memoir and biographical interview.

In attempting to reconstruct in summary Fejtő’s life and political views here I am relying principally on three works. The editions of these I have available to me and have worked on are Ricordi: Da Budapest a Parigi, translated from the original French of 1994 to Italian by Aridea Fezzi Price (Sellerio editore Palermo, 2009); Où va le temps qui passe? Entretiens avec Jacqueline Cherruault-Serper (Éditions Balland, 1991) and Le passager du siècle, with Maurizio Serra (Hachette Littératures, 1999). The first is a memoir by Fejtő; the second and third are interviews with him on his life and writings and on the political history of Europe during the twentieth century.

A cosmopolitan family

Fejtő Ferenc (in Hungarian convention the family name comes first) was born in 1909 in Nagykanisza, then part of the Austro-Hungarian, or Habsburg, empire, today a smallish city in southwestern Hungary. If the Austro-Hungarian empire was extravagantly multinational, its subjects speaking a large number of languages, from German, to Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Italian, Yiddish, Ukrainian, Serbo-Croat and others, Fejtő’s own family background was also significantly cosmopolitan.

His paternal grandfather, Abraham (Philippe) Fischel, a Jewish printer from near Prague who came to Budapest to work on the great German-language liberal newspaper the Pester Lloyd, later found work as foreman of a printing works in Nagykanisza, married his employer’s daughter and eventually took over the business himself. Under his management it became a prosperous enterprise, printing official notices and schoolbooks for the state and religious manuals and prayerbooks for the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish confessions. He also established a local newspaper, a weekly that was to become a daily, and a books and stationery shop.

Fejtő’s maternal grandfather had come from Kiskőrös on the central Hungarian plain but settled in Zagreb, today the capital of Croatia. This was the home of his first cousins, whom he often visited as a young man – indeed he much preferred Zagreb to Nagykanisza. Others of his relations had settled in Prague and in Trieste and Fiume (now Rijeka) on the Adriatic and it was at the country house, the casa grande, of an uncle by marriage, in Fiumicello in Friuli, not far from Trieste, that he remembers them all assembling in 1914 during a long summer holiday just before the outbreak of the First World War.

Fejtő’s large, dispersed multinational family, whose first languages were variously Hungarian, Serbo-Croat and Italian, had a lingua franca in German, which all of them spoke easily even from a young age.

Requiem for an empire

Politically, the First World War was a calamity for the defeated powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. The former was subjected to a harsh regime of reparations – a ‘Carthaginian peace’ in John Maynard Keynes’s terms – which many saw as helping pave the way for the rise of Nazism. The latter simply disappeared from the map, its territory dismembered, to be handed over in ample parcels to the new nations of Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (soon to be Yugoslavia) and also to Romania, Italy and Poland, the last of these a nation state again after 123 years of non-existence.

The rump Austrian republic that remained lost its former industrial heartland in Bohemia and became a largely agricultural country. The new Hungary, forced in 1920 to agree to the Treaty of Trianon, lost its access to the Adriatic and was left with a population of just 7.6 million, a little over a third of its pre-war total of 21.9 million. Those areas of the old Kingdom of Hungary in which very substantial populations of Slovaks (in the north) and Romanians (in the Transylvanian southeast) had lived were ceded to Czechoslovakia and Romania. With the territory went more than three million ethnic Hungarians, who thus became substantial national minorities in their new countries.

It is scarcely surprising that many Hungarians have seen the Treaty of Trianon as a major historical injustice. Fejtő argued, particularly in his book Requiem pour un empire défunt (1988), that the settlement was engineered principally by French diplomacy (in cahoots with the francophile Czechoslovak foreign minister Edvard Beneš), its main purpose being to ensure that there could be no possible revival of Habsburg rule in central Europe (the dynasty having long been a historic enemy of France, and also one with close links to the papacy – thus an offence to both French secularist republicanism and Beneš’s freemasonry).

It was therefore essential, in Fejtő’s explanation, not only to reduce Austria to impotence but to shrink Hungary and surround what was left of it with hostile states that would be reliable French allies: Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, the members of the so-called Petite Entente.

Fejtő further maintained that there was little evidence of widespread enthusiasm for full independence – as opposed to greater autonomy ‑ among many of the peoples who had made up Austria-Hungary’s multinational empire. There may well be some truth in this: certainly the victorious powers, France, Britain, the United States and Italy, in spite of their vocal support for the principle of self-determination, seemed curiously unwilling in practice to facilitate its exercise through consultative referendums.

‘Magyarisation machine’

As a child and adolescent, Fejtő was, like his politically liberal father, an unquestioning Hungarian patriot, while retaining an attachment to the Habsburg dynasty. Indeed many decades later he still found a lot to admire in the late nineteenth-century state, where the Magyar (ethnic Hungarian) element, feeling itself threatened by sizeable and growing minorities of Slavs and Romanians, embarked on a policy of assimilation, or magyarisation, a process in which non-Hungarians might adopt Hungarian national identity, normally opting to speak Hungarian and changing their original ethnic birth names to Hungarian ones, as the Fischels did to become Fejtős, or indeed as Jószef Pehm did to become Cardinal Jószef Mindszenty, the combative archbishop of Esztergom who was a prisoner of the communist state from 1948 to 1971.

Assimilation, in one of its forms, was cheerfully described by Béla Grünwald, an adviser to prime minister Count István Tisza, in the following terms: ‘The Hungarian secondary school is like a huge machine, at one end of which the Slovak youths are thrown in by the hundreds, and at the other end of which they come out as Magyars.’

Clearly, such a process could have attractions for the ambitious, particularly perhaps for members of the Jewish community in moving them out of stigma and discrimination, but it may not always have been as positive an experience as Fejtő imagined. He relates how an uncle, settled in Zagreb, became an enthusiast for all things Croatian, stopped speaking Hungarian and eventually changed his name from the Magyar Ottó Bonyhádi to the Slavic Ilya Bačič. While the flood of national transformations in the opposite direction is seen as being merely in the nature of things, Uncle Ottó’s transition is regarded by his family as being, if not offensive, certainly eccentric.

Fejtő was probably not alone among Hungarians in having difficulty understanding why members of ‘minor nationalities’ persisted in cherishing their own languages and cultures, or indeed why they might have resented the fact that social ascension seemed to require them to abandon the culture they had grown up in. A note of incomprehension, even bafflement, is certainly evident in the remark that Fejtő reports his father as having often made to him: ‘The Croats are rather complicated people. They are our Irish.’

From red to white terror

In the aftermath of the First World War Hungary experienced in quick succession a short period of liberal government, a communist coup, foreign invasion and a counter-revolutionary campaign of terror. The government of the liberal pacifist Count Mihály Károlyi, who led the First Hungarian Republic from 1918 to 1919, fell and was replaced by a revolutionary regime in which power lay with the nominal foreign minister, Béla Kun, a former journalist who had been converted to Bolshevism while a prisoner of war in Russia.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted only 133 days. Its support was confined to Budapest and a few other cities and it was never able to even begin to solve the country’s acute economic problems. Militarily, it had been depending on receiving fraternal help from Russia, which in spite of Kun’s close relationship with Lenin, never arrived. Nevertheless, it was not without ambition or lacking in revolutionary zeal. As Tibor Szamuely, the organiser of the paramilitary unit the ‘Lenin Boys’, created to deal with suspected opponents of the revolution, put it:

Those who wish the old regime to return, must be hanged without mercy. We must bite the throat of such individuals. The victory of the Hungarian Proletariat has not cost us major sacrifices so far. But now the situation demands that blood must flow. We must not be afraid of blood. Blood is steel: it strengthens our hearts, it strengthens the fist of the Proletariat … We will exterminate the entire bourgeoisie if we have to!

The military means available to Szamuely, however, were not commensurate with his appetite for revolutionary violence and the Lenin Boys are thought to have chalked up no more than 600 killings during their brief exercise of power.

When ‘order’ was re-established on the back of the invading Romanian army by Admiral Miklós Horthy, the man who was to lead Hungary for the next twenty-four years, the white terror which succeeded the red was of significantly greater severity and included many thousand arrests and prison sentences and a large number of summary executions – or indiscriminate murders – of political leftists, liberals, Jews, or people whose faces just didn’t look right. Figures advanced for the number of fatalities in a vicious campaign that lasted over two years range from one thousand to several thousand.

Conversion by principle

At the time that these convulsions were taking place, young Ferenc Fejtő was moving from his (Jewish) primary school to his (Catholic) secondary school. He and his family remained largely unaffected by the violence: Nagykanisza was not a hot spot. The school run by the Piarist fathers which Fejtő attended prided itself on treating all its students equally, regardless of their confessional background. A young priest who, marking down one of Fejtő’s essays, sneered that it would be absurd to expect a Jew to understand Hungarian history was rebuked by the principal after a complaint was made by Fejtő’s father.

Eventual matriculation, followed by progression to university, was not expected to be a problem. Nor was it: Fejtő shared top marks in the school ex aequo with a number of classmates. But which university? His first choice was the elite Eötvös college in Budapest, a Hungarian equivalent of Paris’s École Normale Supérieure seen as ‘a little island of liberalism in a society that was becoming ever more repressive’.

From the academic point of view there was no problem about admission. But there was the small matter of the numerus clausus, the ceiling that was placed on the proportion of ‘minority’ (that is Jewish) students permitted to attend any university. In a law of 1920 – probably the first antisemitic legislation of the interwar period – the Hungarian parliament set this at six per cent. The obstacle was not insurmountable, however. Sensing perhaps that Fejtő was not a practising Jew, the university director suggested to him that he might consider going through a – purely formal – Christian baptism.

This presented the young man with a dilemma. Under the influence of his best friend at school he had in fact for some time felt himself growing closer to Catholicism. Now it was being suggested that he should take the final step – but for personal advancement rather than out of intellectual and spiritual conviction. This was unacceptable to him. His solution was to enter a different university, at Pécs, not far from Nagykanisza, where the numerus clausus would not be a problem, and then to convert to Catholicism as an independent act.

A requirement of this conversion was that he would visit the Chief Rabbi to inform him of his decision. This ‘Rembrandtian figure’, dignified and severe, found it hard to believe that the conversion of a Jew to Christianity could be motivated by any other motive than opportunism. Nor, he warned, would he find easy acceptance among the Gentiles, who would always regard him as ‘a defector, a suspect, a traitor’. Fejtő, however, did not relent and was eventually dismissed from the rabbi’s presence with what seemed like a curse.

Jailed Marxist

Pécs was to prove too provincial for Fejtő and he soon transferred to the university of Budapest, where he became deeply immersed in his studies in literature and philosophy and was also drawn to radical politics. Together with a handful of fellow students he set up a Marxist study group: some of its members, and in particular one, László Rajk, were to become important figures in the later history of Hungarian communism. ‘The movement,’ Fejtő wrote, ‘must have been meeting a need, for inside a few months our numbers had reached over a hundred, chiefly the sons of the bonne bourgeoisie, the son of a well-known literary critic, of a Protestant bishop, of a sub-prefect.’

The student Marxists set up an underground review, Szabadon (‘At Liberty’), which was quickly suppressed by the state after an extreme right-wing newspaper wrote that it was a scandal that the producers of such a sheet should remain at liberty. Szabadon was followed in early 1932 by Váloság (‘Reality’), whose publication was subsidised by the underground communist party on condition that Fejtő share the editorial role with his close friend the poet Attila József, whose judgement – in spite of, or perhaps because of, his intellectual brilliance ‑ the party did not fully trust.

In June 1932 Fejtő and a handful of his friends were arrested for their subversive activities. He was interrogated by the police for three days, during which time he was regularly beaten. Then he was sent to jail, where he spent almost a year, in circumstances which he later described as ‘tolerable’: the prison staff were not particularly hostile to political prisoners and he had access to books and paper; the only real hardship was the cold.

It was while in prison that he learned that the Nazis had taken power in Germany. This came as a huge shock to many of his comrades but less so to Fejtő and his friend Jószef, who had felt for some time that the Moscow-directed German communist strategy of ‘class against class’, in which the social democrats (‘social fascists’) rather than the Nazis were identified as the chief enemy of the working class, was heading inexorably towards disaster.

Escape of a social democrat

In 1934 Fejtő joined the Hungarian social democratic party, where for the first time, often through giving classes and lectures in its well-subscribed educational services, he was to meet actual workers. In 1933 he had married, and at first he and his wife, Rose, lived in very straitened circumstances. But his position improved when a sympathetic publisher commissioned him to write a travel book and hired him as editorial assistant on a large encyclopedia project.

He was also able, in conjunction with Attila Jószef and Pál Ignotus, to found another literary-political review, Szép Szó (Arguments, or Persuasion), an anti-fascist journal which, Jószef insisted, would be uncompromising in promoting humanistic and democratic values. In December 1937 however, Jószef, who had long suffered from fragile mental health, took his own life.

A few months later came the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany); the nazification of Hungary seemed to have come a decisive step closer. After writing an account in the social democratic newspaper of a meeting he and others had held with a group of agricultural workers in central Hungary, Fejtő was again arrested and charged with ‘incitement to class struggle’. He was sentenced to six months in prison.

Deciding that with the imminent threat of a fascist takeover and a new regime that would be more savage than Horthy’s, this was no time to be deprived of his liberty, Fejtő resolved to leave the country before his sentence could be enacted. The court had not demanded the surrender of his passport and so he immediately applied to the French embassy for a visa, which was granted. He slipped out of Hungary, travelling through Yugoslavia into Italy and then to France. The first part of his life was over.

As the German army arrived in Paris in June 1940 the Fejtős left the city, fleeing first to Brittany and then to the deeply rural Pech del Luc not far from Cahors in the (then) unoccupied southern zone of France. Here, following the 1944 Allied landings in Normandy, Fejtő became involved with a local unit of the Resistance.

‘Salami tactics’

After the Liberation he returned to Paris, where he was offered work with the foreign service of French radio, which was organising broadcasts into central and eastern Europe, including Hungary. The initial offer, however, was soon withdrawn – though not without embarrassment – when the radio executive concerned was informed by a delegation from the communist Resistance that Fejtő’s candidacy was unacceptable given his known links to the extreme right and activity as a police informer in Hungary, together with his more recent record of collaboration with the enemy in occupied France.

Fejtő offered to demonstrate that these allegations were fabrications, but the executive asked him to show some understanding of his position: he had just started in a new job and did not want to kick off his tenure with a stormy ‘affair’. Fejtő eventually found alternative work with the newly established Agence France Presse monitoring news sources in central Europe.

Late in 1946 Fejtő took a trip back to Hungary, where he located his stepmother, who told him of the fate of his father and brother, both of them vanished into the extermination camps. Some of his social democratic friends invited him to stay on, speaking of a possible post in the administration. He declined.

In a series of actions paralleled in various other central and eastern European states in the immediate postwar period, Hungary’s communists now vigorously embarked on the task of turning a democracy into a ‘people’s democracy’. Employing what party leader Mátyás Rákosi later called ‘salami tactics’ (szalámitaktika) – that is dealing with each of their potential rivals one by one and preventing them from allying together – the communists, now regrouped in the new-minted Hungarian Working People’s Party after a manipulated fusion with the social democrats (1948), managed to destroy first the Independent Smallholders Party, which had won 57 per cent of the vote in the first postwar election, and then every other political rival.

The communists progressed from 17 per cent support in the 1945 general election, to 22 per cent in 1947, to 97 per cent, on a voter turnout of 95 per cent, in 1949. Democracy had been perfected.

In defence of László Rajk

The year of the great communist electoral victory was also the year in which Fejtő’s longtime friend László Rajk, who had been first interior minister and then foreign minister in postwar Hungarian governments, was put on trial for treason. Rajk’s trial, along with those of Traicho Kostov in Bulgaria (1949), Koçi Xoxe in Albania (1949) and Rudolf Slánský in Czechoslovakia (1952), was one of a series of staged events modelled on the Soviet show trials of the 1930s, in which leading communists were accused of – and admitted to – conspiring with the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, or with the imperialist western powers, or both, to undermine the power of the party and restore capitalism (the case against Slánský and his co-defendants, mostly Jews, also had an ‘antizionist’ dimension).

The main purpose of the trials seems to have been to intimidate the satellite states and send a message to any elements in the various parties tempted to follow a ‘national communist’ line, as Tito had done, breaking with or appearing reluctant to follow the ‘advice’ of Stalin and Moscow. There was probably also an element of inner-party score-settling, or of removing political rivals perceived as a threat, as Rajk may well have been seen by party boss Rákosi.

János Kádár (left) and László Rajk (right) at the first national meeting of the Hungarian Communist Party in 1945. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Fejtő at this point proposed to Emmanuel Mounier, the editor of the Christian personalist review Esprit, that he write for him an analysis of the proceedings of the Rajk trial (which ended with the condemnation of the accused and his supposed co-conspirators, followed by his execution on 15 October 1949).

Mounier was sceptical at first, and the French communist party sent the journalist Pierre Courtade, who had been present at the trial and reported on it for the party paper, l’Humanité, to warn him about Fejtő, who, in line with the usual list of accusations, was a former fascist, a police spy and a collaborator. Mounier asked him to provide some proof of these allegations. Courtade departed promising to do so, but never returned.

Why was Fejtő concerned to defend Rajk’s good name? Certainly he had been a friend, and in spite of their divergent political paths they appear to have retained some mutual affection. But Rajk was no humanitarian (Fejtő praised him as ‘a puritan without personal ambition’). He had been a political commissar in the Spanish Civil War and had been instrumental, as interior minister in the postwar period, in setting up the Hungarian secret police (AVH) and managing the transition to ‘people’s democracy’.

Perhaps Fejtő saw sufficient reason to make the intervention he did chiefly in the interests of truth-telling, given the rather obvious fact that the Rajk trial was a travesty, the accused parroting his memorised admissions of guilt in a robotic monotone, once even missing a beat and supplying the scripted answer to a question that had yet to be asked.

Fejtő went so far as to ask the celebrated French defence barrister Vincent de Moro-Giafferri if he would preside over a ‘counter-trial’ (as he had once done for Georgi Dimitrov, accused by the Nazis in connection with the Reichstag fire). Moro-Giafferri asked Fejtő how could it be that a person would openly admit in court committing such serious crimes if he was in fact innocent of them? Fejtő mentioned torture, threats to family, false promises of clemency, and finally brainwashing, leading to the communist accused agreeing to perform ‘one last service to the party’ – the scenario explored through the person of the old Bolshevik Rubashov in Arthur Koestler’s novel Darkness at Noon.

The lawyer listened before replying: ‘If that’s the case let’s drop the subject; your man does not interest me. If I’ve understood correctly, the whole thing comes down to a settling of scores between communists. Rajk is perhaps innocent of what he has been accused of on the instructions of the party, but he is guilty of fanaticism. If the party had ordered him to accuse and have condemned other innocent people he would have complied with that order.’ It is difficult not to have some sympathy with this analysis.

From softening to suppression

The death of Stalin in 1953 unleashed a power struggle between leading party figures ambitious to replace him or to wield significant influence on the future direction of the Soviet Union. The major contenders were Nikita Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov and Lavrentiy Beria, the last of these quickly marginalised and executed and the first – Khrushchev – eventually becoming the dominant figure.

The relative softening of the Moscow line associated with Khrushchev, emphasised by his distancing of the party from the cult of Stalin at the Twentieth Congress in 1956, soon had effects in Russia’s near-abroad. Following rioting in Poznań in Poland, which led to many workers’ deaths, a high-level Soviet delegation including Khrushchev flew in to Warsaw to assess the situation.

Reassured by Polish party officials that they saw the disturbances as having a purely domestic import and had no intention of breaking the alliance with Moscow, the Soviets acquiesced in the rehabilitation of reform-minded ‘national communist’ Władysław Gomułka, who had been imprisoned by the more Stalinist elements of the party, and his appointment as first secretary.

In Hungary events were not to be so easily contained. A student protest outside the state radio headquarters in Budapest in October 1956 developed into much wider unrest after AVH units fired on the students, killing several of them. Elements of the populace formed militias, which attacked the AVH and known communists, many of whom were lynched. Widespread street fighting followed, with a high casualty rate. Some elements of the national army went over to the rebels. A newly appointed Hungarian government under reform communist Imre Nágy declared that the country intended to leave the Warsaw Pact, become a neutral state and progress towards multi-party elections. Russian troops stationed in Hungary were mobilised, but later tactically stood down. Some leading communist officials fled to the Soviet Union. Then the Russians hit back.

The Red Army entered Budapest in force on 4 November and almost immediately retook all strategic locations in the city. Sporadic fighting continued until 11 November, with resistance being fiercest in the industrial and working class area of Csepel. The Hungarian dead have been estimated at 2,500, while the Russians may have lost 700 men. Imre Nágy and General Pál Maléter, the military leader of the uprising, were executed, along with perhaps 350 other insurgents. As many as 200,000 people fled the country.

On the evening of 3 November, Fejtő had spoken by phone with Julia Rajk, widow of László, who assured him that no one in Nágy’s circle believed that the Russians would actually intervene militarily in Hungary. On the following day he went to a meeting at Esprit, where he found that the supporters of that review also could not bring themselves to believe that ‘the Soviet Union, peaceful, progressive, anti-imperialist, would be capable of crushing with arms a revolution that had declared itself socialist and proletarian’.

Tomorrow’s defectors

The suppression of the Hungarian revolution of 1956 by Russian tanks was the event that most seriously shook support for communism in western Europe in the latter half of the twentieth century. The Communist Party of Great Britain, whose strength, such as it was, lay in the trade union movement and in some intellectual quarters rather than in parliament, lost a quarter to a third of its members over the following few years.

Most of the members of the prestigious Communist Party Historians Group – eminent scholars such as Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Victor Kiernan, Raphael Samuel, John Savile, Edward (EP) and Dorothy Thompson – left the party in 1956 or in the years immediately following. However Britain’s most distinguished Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, did not leave, though, as he was to report in his memoir Interesting Times, he ‘recycled myself from militant to sympathizer or fellow-traveller, or, to put it another way, from effective membership of the British Communist Party to something like spiritual membership of the Italian CP’.

The Italian party, however, had had its own revolt when a number of party intellectuals and sympathisers, in late October 1956, drafted the Manifesto dei 101 expressing solidarity with the Hungarian uprising and submitted it to the party newspaper, L’Unità ‑ which refused to publish it. The PCI, however, in subsequent years certainly granted its associated intellectuals a longer leash than was customary for western European communist parties, while still maintaining its essential loyalty to Moscow.

Though Fejtő throughout his long life kept his eye on central and eastern Europe, both in his largely anonymous professional work as a regional specialist for AFP and in his more pointed essays for literary-political reviews, he fought his ideological battles in Paris, a city in which intellectuals have a certain importance, and a certain sense of their own importance. His postwar years were in some respects parallel to those of the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz.

Miłosz served Poland (fully communist after 1947) as a cultural attaché from 1945 to 1951, in the US and in France. Fejtő, between two stints at AFP, worked in the press office of the Hungarian embassy in Paris during the period when the democratic system at home was coming under increasing pressure.

Miłosz later wrote that Paris, where he sought political asylum and then settled in rather precarious material circumstances, was an uncomfortable place for a defector from a socialist society in the making to live: the city’s ‘progressive’ intelligentsia, he felt, was gripped by a Stalinising pensée unique and so a writer who had ‘fled from a country where Tomorrow was being born’ was an embarrassment, someone ‘guilty of a social blunder’.

Miłosz also suffered from the bitter hostility of a previous wave of Polish émigrés who correctly identified him as a man of left-wing sensibilities and one whom they were not inclined to ever forgive for having served the new government in Warsaw. He thus perhaps found himself in the situation forecast by the Chief Rabbi of Nagykanisza, where someone who ‘switches faith’ comes to be regarded as ‘a defector, a suspect, a traitor’, accepted neither by the group he has left nor those in whose bosom he has sought refuge.

Resisting conversion

Though Fejtő, by contrast, was buoyed up in Paris by a number of close friendships, we have seen that he still had some difficulties with colleagues who were reluctant to see it clearly spelled out that the Russians were doing what in fact the Russians were doing. Some of these gradually allowed themselves to be persuaded that there was a moral imperative to tell the truth.

Others continued to resist, unwilling, as they put it, to ‘play the game of the imperialists’ by pointing out the shabby reality of what later came to be known as ‘actually existing socialism’. Members of this tendency, which existed in many countries and not just France, were sometimes referred to as ‘the anti-anti-communists’.

The task of keeping their members and sympathisers on side in the face of ‘bad press’ had always been a troublesome one for communist parties. For many years, throughout the 1920s, the élan of the initial Bolshevik victory and the successful defence of the Soviet Union against ‘white’ reaction and foreign intervention made for a heroic story which had considerable mythic power among the working class of western Europe and even in the United States. The internal struggles of the 1930s, and the Stalinist purges, show trials and famines, were another matter. There was a lot to explain away:

…more than one and a half million arrests, 1,345,000 condemnations, more than 690,000 executions in the years 1937 and 1938 alone … the disappearance of the absolute majority of the party central committee between 1917 and 1923, of three party secretaries between 1919 and 1921, of the majority of the politburo between 1919 and 1924, of 108 of the 134 members of the central committee [designated at the party congress of January 1934] and 1,108 of the 1,966 delegates who participated in it…(Michel Laval, L’Homme Sans Concessions: Arthur Koestler et son siècle)

How did those who were aware of these enormities and of the huge economic problems in the USSR (far from every communist or sympathiser) deal with that knowledge? Through ‘dialectics’ was Koestler’s answer. Living standards in the Soviet Union were low, but they had been lower. And workers in the capitalist countries were indeed better off. But facts had to be understood in a dynamic, not static, way. The conditions for Soviet workers were improving, whereas for western ones they were deteriorating. In the meantime, it was best if the working class be shielded from truths that it was as yet not intellectually mature enough to process.

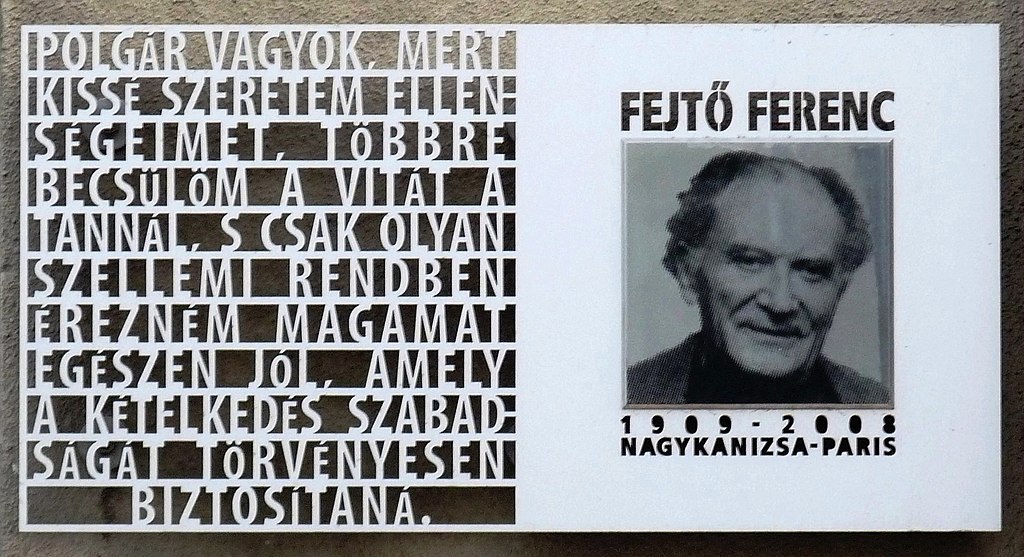

Commemorative plaque to Ferenc Fejtő in Nagykanizsa. ‘I am a citizen, because I am a little fond of my enemies, I value debate more than doctrine, and I would only feel quite comfortable in an intellectual order which would legally guarantee freedom of doubt’. Photo by Fekist via Wikimedia Commons.

For others, repelled by the repression of the 1930s and even more so by the Hitler-Stalin pact, conversion came later. For the French writer Edgar Morin, who joined the Resistance and the communist party during the war and later became a friend and intellectual collaborator of Fejtő, there was one event that ‘changed everything’.

Stalingrad wiped away for me, and without doubt for thousands like me, all the crimes, doubts and hesitations … Stalin was identified with the city named after him, the city with the Red October factory with its workers in arms, the factory with the 1917 revolution, and all of those with the freedom of the world, with the victory finally in sight, with all our hopes, with the radiant future … The crimes of Stalinism disappeared in the gigantic massacres of the war.

If we can make a distinction between the fellow-travelling left intellectual who essentially wished to be allowed to continue believing what he or she wanted to believe and the hardened, manipulating, party apparatchik (who may have believed or may not) we should also distinguish both of these types from the rank and file party member whose attachment to communism often sprung from the extremely harsh conditions of life for the working class (conditions which persisted in France, for example, possibly into the 1980s) and the hope which the party offered that these conditions were not just in the nature of things but were associated with a particular mode of organisation of society which could be changed, and indeed in the Soviet Union had been changed.

It would be a mistake, and patronising, to believe that these rank and file members focused only on their own immediate concerns and were ignorant of, or not interested in, events in Russia or eastern Europe. Jeannine Verdès-Leroux’s study Au service du Parti outlined in a series of case studies how aware a number of French party members she interviewed were of the events of 1956 in Russia, Poland and Hungary and the hesitations and often anguished internal debates that attended them making the momentous decision to leave the party – or indeed stay in it.

There were of course those who were never afflicted by uncertainty, being protected by stupidity or arrogance. An example of the first might be the Hungarian Marxist professor Aladár Mód, who reasoned that Fejtő had indeed correctly judged László Rajk to be innocent, a judgement largely determined by his hostility to the party, but that ‘we who had faith in the party’ could not be said to have been wrong since the party had now recognised its errors and rehabilitated Rajk. More pointedly, Pierre Courtade told Edgar Morin: ‘I was right to have been wrong, whereas you and your like were wrong to have been right.’ To apply dialectics correctly obviously requires an agile mind, and sometimes also a strong stomach.

Attack as defence

The Hungarian communist intellectual György Lukács, with whom Fejtő periodically clashed, once declared, perhaps somewhat defensively, that the worst communist regime that existed was superior to the best capitalist one: which gives us Pol Pot as a greater benefactor of humanity than Clement Attlee.

Where does this contempt, this obtuseness and arrogance, come from? From a bad conscience perhaps (and in Lukács’s case possibly a perversity born of the revulsion he felt for his own family background – his father was an investment banker and a baron). But there is also a bullying element, which could derive from the intuition that attack can be the best form of defence and that one’s opponent may be quickly and effectively cowed if sufficient verbal force is applied.

We see this aggression constantly in the extravagant language of abuse of Soviet propaganda, its predilection for dehumanising insults (pygmies, pug dogs and puppies, dregs, vermin, stinking carrion, scum, accursed cross between a fox and a swine, typhus-ridden lice – Soviet state prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky, the maestro of the 1930s show trials, was the master here).

Arguably a similar impulse is at work, though in a more minor key, in Sartre’s pat dismissal of critics of communism, as quoted in the epigraph to this essay. Or even Eric Hobsbawm’s characterisation of ‘those ex-communists who turned into fanatical anti-communists, because they could free themselves from the service of “The God that Failed” only by turning him into Satan’. One might ask how many million deaths one needs to be responsible for before an evocation of the Prince of Darkness is not deemed to be shockingly inappropriate.

A leftist anti-communist

A more delicate, though also important, point is that anti-communism was a spectrum: there were those who journeyed over a lifetime from youthful radicalism to curmudgeonly middle-aged and elderly neoconservatism, a type most often found in the United States (Kristol, Hook, Podhoretz); Koestler too shares much of this itinerary. But there are many others – Orwell, Camus, Sperber, Morin, Howe – who remained intellectually active and never left the left.

Fejtő was one of these. If he claimed in 1984 that he hadn’t changed his politics in fifty years, a careful reading of his memoirs fails to quite bear that claim out. He was in some respects not the quickest or most eager of learners. If he distanced himself from the political line that was imposed on communist parties from Moscow from the early 1930s he did not give up hope that co-operation could be forged between a determined, radical socialism and more humanist elements in communism.

Of the period in the late 1940s when he worked at the Hungarian embassy in Paris, he wrote: ‘I was a unifier; an incorrigible dreamer … I believed, I wanted to believe, that the socialist-communist left would be capable of implementing the reforms I hoped for but would pull up in time before the abyss of a dictatorship.’

After Hungary in 1956, after Prague in 1968 (indeed possibly before it), he was no longer able to sustain that dream. But he did continue to think and write about left politics, analysing events as they developed for AFP and contributing to many journals, in particular Esprit and – with Edgar Morin and Roland Barthes – Arguments. He agreed with Morin that socialists needed to laïciser l’espoir (secularise hope), that is to steer left politics back again from the Marxist-Leninist appropriation of the essentially religious idea of salvation.

He remained sceptical – perhaps overly so – of developments in the 1970s/80s tendency called Eurocommunism, believing that communism under any colours remained wedded to some version of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which meant of the party, and that the democratic election that communists managed to win would probably be the last of its kind.

Late in life, he continued to advise great caution in relations with Moscow: ‘The idea of dictatorship in imperial colours – that’s the heritage of Stalin. It is retained by the postcommunists, and, allied to the most extreme religious orthodoxy, it has survived the collapse of the USSR.’

Personally impelled by a desire to tackle social injustice, and to achieve the maximum of positive social change that could be achieved, Fejtő was wary of those who were convinced they had the recipe for creating heaven on earth and who would not be stopped from attempting to put it into practice. For if heaven is within our grasp, surely it is madness to allow anything to get in the way?

Michel de Montaigne, with an eye to the religiously inspired genocidal impulses and practices of the late sixteenth century, had remarked that it was ‘putting a very high price on one’s conjectures to have a man roasted alive because of them’. The twentieth century amply demonstrated that there was no shortage of people with the ambition and the means to roast, or shoot, or gas vast numbers of people on the basis of their conjectures about the world. It would be reckless to assume that they have entirely gone away.

Published 24 March 2023

Original in English

First published by Dublin Review of Books (1 February 2023)

Contributed by Dublin Review of Books © Enda O'Doherty / Dublin Review of Books / Eurozine

PDF/PRINT

No comments:

Post a Comment