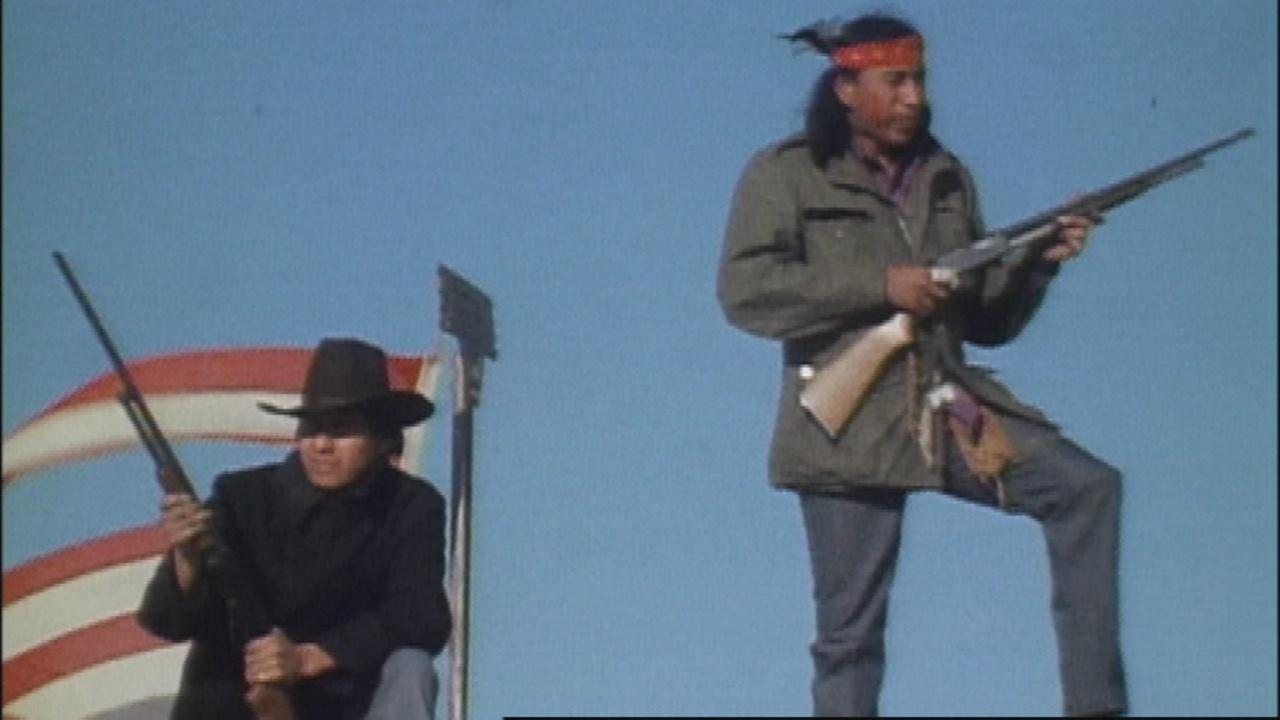

Two AIM members at Wounded Knee in 1973

(Photo: PBS)

BY LEVI RICKERT FEBRUARY 26, 2023

Opinion. Monday marks the 50th anniversary of the takeover of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation on February 27, 1973 by the American Indian Movement (AIM).

The siege would last 71 days and would become known as the Wounded Knee II. Some 83 years earlier, on December 29,1890, the U.S. Cavalry Regiment had massacred some 250 innocent Lakota men, women and children on the same land.

The central figures of the 1973 Wounded Knee takeover are now deceased. AIM co-founder Dennis Banks (Leech Lake Ojibwe) died on October 29, 2017; AIM co-founder Clyde Bellecourt (White Earth Nation) died last year on January 11, 2022; and AIM activist Russell Means (Oglala Sioux) died on October 22, 2012.

In 1973, I was still in my youthful days. I was too young to join in the occupation. Years later, my work in Indian Country allowed me to meet and even interview all three of these historic men. I learned a lot about the 1973 Wounded Knee’s history takeover from Banks and Bellecourt.

My friend Paul Collins, who is an internationally acclaimed artist, through a fate of history was in South Dakota painting a series called Other Voices, A Native American Tableau at the time of AIM’s takeover of Wounded Knee.

The previous year, Chief Frank Fools Crow (Lakota), a spiritual leader, was at the United Nations to speak and Collins was there for his Black Portrait of an African Journey exhibition. Fools Crow was so impressed with Collins’ art, he told Collins he should come to South Dakota to paint the Lakota.

Collins met Dennis Banks at Wounded Knee and the two became very close — so much so that they referred to one another as a “brother from another mother.” Because of the close relationship between the two men, Banks would come to Grand Rapids often during the last years of his life. Many times, unexpectedly, Banks would call me to come visit him at Collins’ home. Depending on my schedule, I would take advantage of visiting him and, after founding Native News Online, interviewing Banks.

Even before Native News Online began publishing, I interviewed Banks on stage at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids in November 2009 in a program called A Conversation with Dennis Banks. The conversation covered a broad range of topics, and at one point, I asked Banks how AIM ended up at Wounded Knee in 1973.

“First there was a historical significance of Wounded Knee,” Banks told me. “It was the scene of an absolute slaughter where over 250 men, women and children were slaughtered by the U.S. military. And, up until that point, there was never no closure to what happened there.

“So Fools Crow says, ‘Let’s go back to Wounded Knee. Let the spirits help defend us there.’ They were the ones (spiritual leaders) who told us to go there.”

Opinion. Monday marks the 50th anniversary of the takeover of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation on February 27, 1973 by the American Indian Movement (AIM).

The siege would last 71 days and would become known as the Wounded Knee II. Some 83 years earlier, on December 29,1890, the U.S. Cavalry Regiment had massacred some 250 innocent Lakota men, women and children on the same land.

The central figures of the 1973 Wounded Knee takeover are now deceased. AIM co-founder Dennis Banks (Leech Lake Ojibwe) died on October 29, 2017; AIM co-founder Clyde Bellecourt (White Earth Nation) died last year on January 11, 2022; and AIM activist Russell Means (Oglala Sioux) died on October 22, 2012.

In 1973, I was still in my youthful days. I was too young to join in the occupation. Years later, my work in Indian Country allowed me to meet and even interview all three of these historic men. I learned a lot about the 1973 Wounded Knee’s history takeover from Banks and Bellecourt.

My friend Paul Collins, who is an internationally acclaimed artist, through a fate of history was in South Dakota painting a series called Other Voices, A Native American Tableau at the time of AIM’s takeover of Wounded Knee.

The previous year, Chief Frank Fools Crow (Lakota), a spiritual leader, was at the United Nations to speak and Collins was there for his Black Portrait of an African Journey exhibition. Fools Crow was so impressed with Collins’ art, he told Collins he should come to South Dakota to paint the Lakota.

Collins met Dennis Banks at Wounded Knee and the two became very close — so much so that they referred to one another as a “brother from another mother.” Because of the close relationship between the two men, Banks would come to Grand Rapids often during the last years of his life. Many times, unexpectedly, Banks would call me to come visit him at Collins’ home. Depending on my schedule, I would take advantage of visiting him and, after founding Native News Online, interviewing Banks.

Even before Native News Online began publishing, I interviewed Banks on stage at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids in November 2009 in a program called A Conversation with Dennis Banks. The conversation covered a broad range of topics, and at one point, I asked Banks how AIM ended up at Wounded Knee in 1973.

“First there was a historical significance of Wounded Knee,” Banks told me. “It was the scene of an absolute slaughter where over 250 men, women and children were slaughtered by the U.S. military. And, up until that point, there was never no closure to what happened there.

“So Fools Crow says, ‘Let’s go back to Wounded Knee. Let the spirits help defend us there.’ They were the ones (spiritual leaders) who told us to go there.”

Dennis Banks, co-founder of the American Indian Movement ,and Levi Rickert at Grand Valley State University for “A Conversation with Dennis Banks” in November 2009.

(Photo/Native News Online)

Banks further explained that AIM could not take over the village of Pine Ridge because of the strong presence of FBI agents and U.S. Marshals there who were positioned on top of buildings. He said AIM did not want to bring attention to them

He told me that he did not realize how far the U.S. government would go to destroy the American Indian Movement.

What happened at Wounded Knee was nothing short of warfare against Indian warriors. Military helicopters and jets flew overhead. Banks explained at one point there were 35 military tanks there and over 130,000 rounds of ammunition were used against AIM. Most nights were filled with gunfire into the cordoned off town from federal marshals and National Guard members.

With the siege of Wounded Knee, all of the sudden American Indian concerns were front and center in the minds of Americans, who for the most part had thought about American Indians on Thanksgiving. This, of course, was the power of being on nightly newscasts on television. The international media even paid attention to the poor treatment of American Indians.

The American Indian Movement allowed for Americans to get past the Disney version of Indian chiefs galloping through the dusty prairies on horseback wearing long war bonnets. The contemporary warriors—American Indian Movement members—wore blue jeans, cowboy boots, headbands and carried guns.

The longer the siege lasted, the pride in being an American Indian tribal member intensified for many throughout America.

The American Indian Movement leaders became new heroes to a new generation of Native Americans. Average Americans had John Wayne to look up to in movies. In real life, Native Americans had Banks, Bellecourt, Means, and others.

At the end of the 71-siege, two Native Americans were killed and another person remains missing until today.

There is no denying the takeover by AIM of Wounded Knee changed the course of history for Native Americans forever. Later that decade, legislation was enacted in support of Native American rights, including the 1978 American Indian Freedom of Religion Act and the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Fools Crow was right. Maybe there was some closure to what happened to 250 innocent Native Americans in 1890 at Wounded Knee as the result of AIM’s takeover in 1973.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

Madonna Thunder Hawk: A Firsthand Personal Account of Wounded Knee 1973

Today is the 50th anniversary of the American Indian Movement's takeover of Wounded Knee.

Banks further explained that AIM could not take over the village of Pine Ridge because of the strong presence of FBI agents and U.S. Marshals there who were positioned on top of buildings. He said AIM did not want to bring attention to them

He told me that he did not realize how far the U.S. government would go to destroy the American Indian Movement.

What happened at Wounded Knee was nothing short of warfare against Indian warriors. Military helicopters and jets flew overhead. Banks explained at one point there were 35 military tanks there and over 130,000 rounds of ammunition were used against AIM. Most nights were filled with gunfire into the cordoned off town from federal marshals and National Guard members.

With the siege of Wounded Knee, all of the sudden American Indian concerns were front and center in the minds of Americans, who for the most part had thought about American Indians on Thanksgiving. This, of course, was the power of being on nightly newscasts on television. The international media even paid attention to the poor treatment of American Indians.

The American Indian Movement allowed for Americans to get past the Disney version of Indian chiefs galloping through the dusty prairies on horseback wearing long war bonnets. The contemporary warriors—American Indian Movement members—wore blue jeans, cowboy boots, headbands and carried guns.

The longer the siege lasted, the pride in being an American Indian tribal member intensified for many throughout America.

The American Indian Movement leaders became new heroes to a new generation of Native Americans. Average Americans had John Wayne to look up to in movies. In real life, Native Americans had Banks, Bellecourt, Means, and others.

At the end of the 71-siege, two Native Americans were killed and another person remains missing until today.

There is no denying the takeover by AIM of Wounded Knee changed the course of history for Native Americans forever. Later that decade, legislation was enacted in support of Native American rights, including the 1978 American Indian Freedom of Religion Act and the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Fools Crow was right. Maybe there was some closure to what happened to 250 innocent Native Americans in 1890 at Wounded Knee as the result of AIM’s takeover in 1973.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

Madonna Thunder Hawk: A Firsthand Personal Account of Wounded Knee 1973

Today is the 50th anniversary of the American Indian Movement's takeover of Wounded Knee.

BY MADONNA THUNDER HAWK

FEBRUARY 27, 2023

Guest Opinion. Today, I share with you the story of my experience on the ground during that monumental moment. I’ll talk about the way things unfolded and how those weeks under siege were the first domino in a series of events that catapulted our movement into the international spotlight — and also eventually led to the formation of the Lakota People’s Law Project.

By the time the standoff began that February, I was already a seasoned activist. I’d met with the local American Indian Movement (AIM) chapter in the Twin Cities in the 1960s, and I’d joined relatives in California to occupy Alcatraz. When the call went out from the people of Pine Ridge to help lead discussions to confront issues in their communities, I didn’t hesitate. Little did I know that a planned series of strategy meetings would turn into an epic, months-long siege that would threaten our lives and gain international media attention.

On the evening of February 27, 1973, after we finished talking with folks in a village called Calico, our caravan headed toward Porcupine. We were several miles north of Wounded Knee when the word went out that the feds were upon us. Armored personnel carriers had been spotted, and the Army, FBI, and other law enforcement agencies were converging on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. We realized we had to get the caravan and our people to safety. And when we got to the village of Wounded Knee, the first firefight started.

Many people, including everyone in our car, got arrested that night, and for the first four or five nights of the occupation, I was in jail. Once released, I did what everyone else was doing: I loaded up on supplies and headed back to Wounded Knee. And there I remained until the siege ended more than two months later.

On the ground, it was minute to minute, day to day. It was a full military action, and we never knew what would happen. Firefights occurred almost every night, with flares and tracers raining down to light up the area. My job — I was one of four women doing this — was as a medic. We each had different bunkers to cover in case someone got shot. I was assigned four bunkers on the south side. Every night, it was nonstop activity. People would sneak in and out, hiding in the grass, bringing food and other supplies. Many were arrested. In that situation, you’re just trying to make sure everyone’s alive and healthy. If you couldn’t find someone, you wondered if they’d been killed or taken to jail.

During this time, I met Danny Sheehan, who would go on to lead several seminal legal justice fights and become our Lakota Law president and chief counsel. During the standoff, Danny was staying with my brother-in-law, Herman Thunder Hawk, in the house where we monitored government communications via CB radio. He was among many legal volunteers who showed up when it mattered most, and he stayed busy prepping criminal defenses for our people. It’s notable that no one was ever convicted after the standoff. All charges were eventually dismissed because of prosecutorial misconduct. The FBI had illegally wiretapped attorneys.

Those weeks under siege were hard, but they were worth it. We took a stand that mattered, and we held the world’s attention on nightly newscasts. We inspired later landback and occupy movements, and we formed connections that last until the present day. 32 years later, in 2005 — when South Dakota’s Department of Social Services wouldn’t stop taking our children — Russell Means urged me to talk with Danny again, leading to the founding of Lakota Law. We’ve been in this fight together, off and on, for half a century.

Madonna Thunder Hawk is the Cheyenne River organizer for The Lakota People’s Law Project.

Guest Opinion. Today, I share with you the story of my experience on the ground during that monumental moment. I’ll talk about the way things unfolded and how those weeks under siege were the first domino in a series of events that catapulted our movement into the international spotlight — and also eventually led to the formation of the Lakota People’s Law Project.

By the time the standoff began that February, I was already a seasoned activist. I’d met with the local American Indian Movement (AIM) chapter in the Twin Cities in the 1960s, and I’d joined relatives in California to occupy Alcatraz. When the call went out from the people of Pine Ridge to help lead discussions to confront issues in their communities, I didn’t hesitate. Little did I know that a planned series of strategy meetings would turn into an epic, months-long siege that would threaten our lives and gain international media attention.

On the evening of February 27, 1973, after we finished talking with folks in a village called Calico, our caravan headed toward Porcupine. We were several miles north of Wounded Knee when the word went out that the feds were upon us. Armored personnel carriers had been spotted, and the Army, FBI, and other law enforcement agencies were converging on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. We realized we had to get the caravan and our people to safety. And when we got to the village of Wounded Knee, the first firefight started.

Many people, including everyone in our car, got arrested that night, and for the first four or five nights of the occupation, I was in jail. Once released, I did what everyone else was doing: I loaded up on supplies and headed back to Wounded Knee. And there I remained until the siege ended more than two months later.

On the ground, it was minute to minute, day to day. It was a full military action, and we never knew what would happen. Firefights occurred almost every night, with flares and tracers raining down to light up the area. My job — I was one of four women doing this — was as a medic. We each had different bunkers to cover in case someone got shot. I was assigned four bunkers on the south side. Every night, it was nonstop activity. People would sneak in and out, hiding in the grass, bringing food and other supplies. Many were arrested. In that situation, you’re just trying to make sure everyone’s alive and healthy. If you couldn’t find someone, you wondered if they’d been killed or taken to jail.

During this time, I met Danny Sheehan, who would go on to lead several seminal legal justice fights and become our Lakota Law president and chief counsel. During the standoff, Danny was staying with my brother-in-law, Herman Thunder Hawk, in the house where we monitored government communications via CB radio. He was among many legal volunteers who showed up when it mattered most, and he stayed busy prepping criminal defenses for our people. It’s notable that no one was ever convicted after the standoff. All charges were eventually dismissed because of prosecutorial misconduct. The FBI had illegally wiretapped attorneys.

Those weeks under siege were hard, but they were worth it. We took a stand that mattered, and we held the world’s attention on nightly newscasts. We inspired later landback and occupy movements, and we formed connections that last until the present day. 32 years later, in 2005 — when South Dakota’s Department of Social Services wouldn’t stop taking our children — Russell Means urged me to talk with Danny again, leading to the founding of Lakota Law. We’ve been in this fight together, off and on, for half a century.

Madonna Thunder Hawk is the Cheyenne River organizer for The Lakota People’s Law Project.

SEE

No comments:

Post a Comment