Methane from megafires: more spew than we knew

Novel detection technique raises pollution policy questions

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: WILDFIRE EMISSIONS POLLUTING THE VIEW IN 2020. view more

CREDIT: FRAUSTO-VICENCIO/UCR

Using a new detection method, UC Riverside scientists found a massive amount of methane, a super-potent greenhouse gas, coming from wildfires — a source not currently being accounted for by state air quality managers.

Methane warms the planet 86 times more powerfully than carbon dioxide over the course of 20 years, and it will be difficult for the state to reach its required cleaner air and climate goals without accounting for this source, the researchers said.

Wildfires emitting methane is not new. But the amount of methane from the top 20 fires in 2020 was more than seven times the average from wildfires in the previous 19 years, according to the new UCR study.

“Fires are getting bigger and more intense, and correspondingly, more emissions are coming from them,” said UCR environmental sciences professor and study co-author Francesca Hopkins. “The fires in 2020 emitted what would have been 14 percent of the state’s methane budget if it was being tracked.”

The state does not track natural sources of methane, like those that come from wildfires. But for 2020, wildfires would have been the third biggest source of methane in the state.

“Typically, these sources have been hard to measure, and it’s questionable whether they’re under our control. But we have to try,” Hopkins said. “They’re offsetting what we’re trying to reduce.”

Traditionally, scientists measure emissions by analyzing wildfire air samples obtained via aircraft. This older method is costly and complicated to deploy. To measure emissions from 2020’s Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex in the Sierra Nevadas, the UCR research team used a remote sensing technique, which is both safer for scientists and likely more accurate since it captures an integrated plume from the fire that includes different burning phases.

The technique, detailed in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, allowed the lead author, UCR environmental sciences Ph.D. student Isis Frausto-Vicencio to safely measure an entire plume of the Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex gas and debris from 40 miles away.

“The plume, or atmospheric column, is like a mixed signal of the whole fire, capturing the active as well as the smoldering phases,” Hopkins said. “That makes these measurements unique.”

Rather than using a laser, as some instruments do, this technique uses the sun as a light source. Gases in the plume absorb and then emit the sun’s heat energy, allowing insight into the quantity of aerosols as well as carbon and methane that are present.

Using the remote technique, the researchers found nearly 20 gigagrams of methane emitted by the Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex. One gigagram is 1,000 metric tons. An elephant weighs around one metric ton. For context, the fire therefore contained roughly 20,000 elephants’ worth of the gas.

This data matches measurements that came from European space agency satellite data, which took a more sweeping, global view of the burned areas, but are not yet capable of measuring methane in these conditions.

If included in the California Air Resources Board methane budget, wildfires would be a bigger source than residential and commercial buildings, power generation or transportation, but behind agriculture and industry. While 2020 was exceptional in terms of methane emissions, scientists expect more megafire years going forward with climate change.

In 2015, the state first established a target of 40 percent reduction in methane, refrigerants and other air pollutants contributing to global warming by 2030. The following year, in 2016, Gov. Jerry Brown signed SB 1383, codifying those reduction targets into law.

The reductions are meant to come from regulations that capture methane produced from manure on dairy farms, eliminate food waste in landfills, require oil and gas producers to minimize leaks, ban certain gases in new refrigerators and air conditioners, and other measures.

“California has been way ahead on this issue,” Hopkins said. ‘We’re really hoping the state can limit the methane emissions under our control to reduce short-term global warming and its worst effects, despite the extra emissions coming from these fires.”

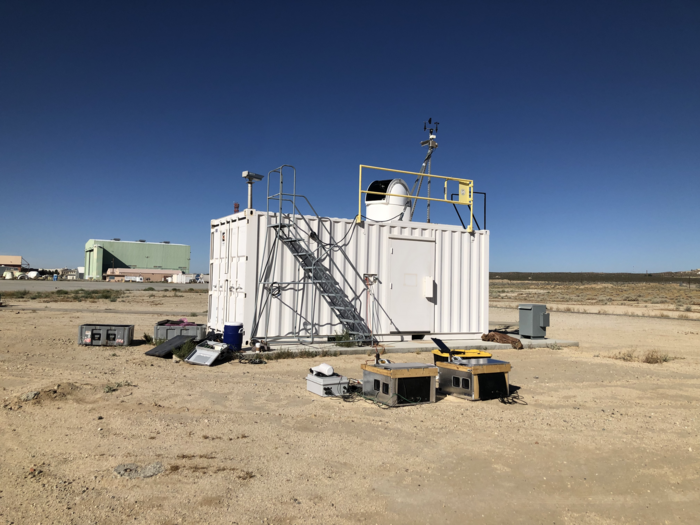

Riverside and Los Alamos National Laboratory measuring wildfire emissions from a safe distance.

Riverside and Los Alamos National Laboratory measuring wildfire emissions from a safe distance.

Portable solar spectrometers measuring alongside a higher resolution solar spectrometer. Researchers performed side-by-side measurements before and after field campaigns to ensure instrument stability and check data quality. Photo taken at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California.

Portable solar spectrometers measuring alongside a higher resolution solar spectrometer. Researchers performed side-by-side measurements before and after field campaigns to ensure instrument stability and check data quality. Photo taken at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California.

CREDIT

Frausto-Vicencio/UCR

Frausto-Vicencio/UCR

JOURNAL

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics

ARTICLE TITLE

Ground solar absorption observations of total column CO, CO2, CH4, and aerosol optical depth from California's Sequoia Lightning Complex Fire: emission factors and modified combustion efficiency at regional scales

ARTICLE PUBLICATION DATE

14-Apr-2023

No comments:

Post a Comment