Symposium marks 130th anniversary of Swami Vivekananda’s arrival in the United States

Swami Vivekananda’s tour of the United States would mark what would become the first exposure most non-Hindus in the West had with Hinduism.

(RNS) — In July 1893, a young Hindu monk from Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, arrived in the United States. His goal was to make the West aware of Hinduism, one of the world’s oldest faiths yet one that had been largely misunderstood, misinterpreted and vilified by the West.

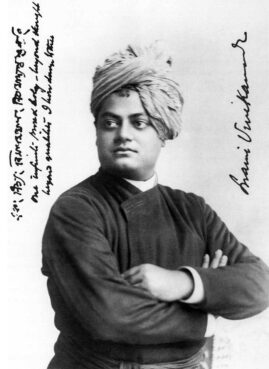

Swami Vivekananda’s tour of the United States would mark what would become the first exposure most non-Hindus in the West had with Hinduism. Swami Vivekananda, born Narendranath Datta, was barely 30 years old and transformed into an international ambassador of the faith, thanks to his electrifying speeches at the 1893 Parliament of World’s Religions in Chicago and in invited lectures across the country.

Vivekananda became known as Hinduism’s missionary to the world, despite not seeking to convert others. His teachings were widespread around the United States, particularly through the propagation of Vedanta philosophy, the core of the Vedas, and the establishment of Vedanta Societies.

To mark the 130th anniversary of his arrival, the Free Library of Philadelphia and followers of Vivekananda’s philosophy have organized a symposium on his teachings, his message and his impact this Saturday. The April 29 symposium, which will be both in person and virtual, will feature talks by Swami Tyagananda, the head of the Vedanta Society in Boston and the Hindu chaplain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard; Deven Patel, associate professor of South Asian studies at the University of Pennsylvania; and Jeffery D. Long, professor of religion, philosophy and Asian studies at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. The Rev. Stephen Avino, executive director of this year’s Parliament of World’s Religions, will also provide remarks on Vivekananda’s impact in understanding faith beyond an Abrahamic lens.

Long said Swami Vivekananda has an enduring legacy because he articulated the idea of religion and spirituality being a personal quest of self-improvement rather than collective tethering to dogma and doctrine.

“Swami Vivekananda spoke to universal concerns which are likely to remain relevant in all times and places: the quest for spirituality, and for a deeper meaning and purpose in life, and issues like the nature of consciousness, the nature of self, and the foundations of ethics,” he said. “Swami Vivekananda advocated for the freedom of individuals to pursue questions fearlessly, without being bound by dogmatism. His teaching is reflected in the emergence of the ‘spiritual but not religious movement.'”

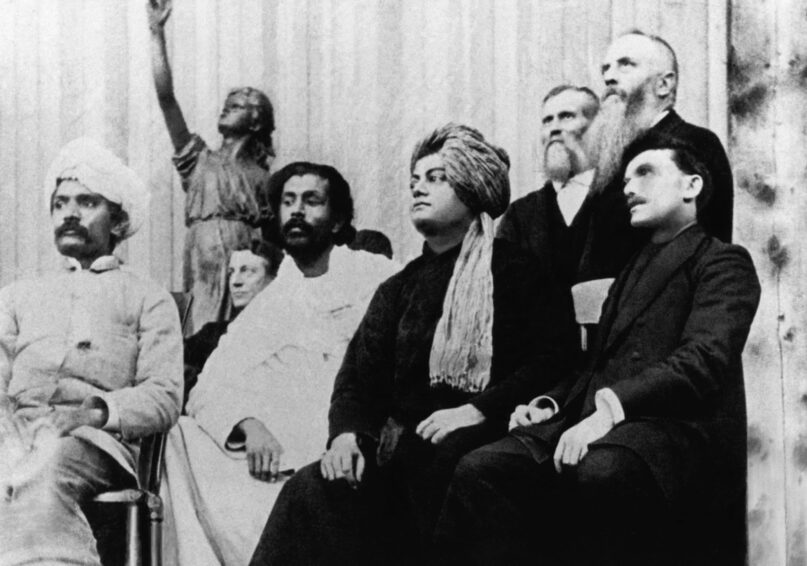

Swami Vivekananda in Chicago during the Parliament of the World’s Religions in September 1893. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Divya Nair, a member of the Vedanta Society and a key organizer of the symposium, said Swami Vivekananda’s message of pluralism and personal connection to the divine remains powerful today.

“Often we think of religion as something apart from us but Swamiji teaches us to dive deep inward, tap into our innate strength and change our perception of what we are seeing,” Nair said. “As we encounter calamities of various scales and magnitudes today, this lesson is so important: We gain the strength to bear witness calmly and persevere patiently in our search for peace, reality and truth, no matter who or where we are.”

Leading up to the symposium, organizers have held weekly sessions on Vivekananda’s teachings, led by Patel. Nair said attendees have shared how much they have been inspired by the lessons and how much they learned about the pioneering monk.

A philosopher and activist ahead of his time

What made Swami Vivekananda so influential to Hindus and non-Hindus was his marriage of Hindu philosophy with practice. A disciple of the Hindu spiritual leader Sri Ramakrishna, Vivekananda explained the idea of yoga to the West. While the physical practice of yoga would become slowly separated from its Hindu philosophical roots in later years, Vivekananda was important in demystifying it to curious Westerners.

He was also one of the first international visitors to the United States to speak out against racial injustice. During one of his tours in the American South, Vivekananda spoke out against the segregation of train cars and other facilities, refusing to sit in the “whites only” section of a train, a privilege initially made possible by a white benefactor who sponsored his speech in Tennessee.

In India, Vivekananda spoke forcefully against the caste system, arguing it went against Hindu scriptures and was not indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. Though Vivekananda’s message was not different from that of hundreds of well-known Hindu sages, reformers and lay leaders who came before him, his impact was more pronounced because of his ability to articulate ideas to both Hindu audiences and British colonial authorities. Caste only became a legal identity in India during the British Raj in the 1800s, but Vivekananda argued any form of casteism ran counter to the core of Vedic philosophy, which teaches the oneness of all beings.

He also argued against the politicization of religion, particularly as it became weaponized to divide different groups.

“Swami Vivekananda spoke against fanaticism, bigotry and intolerance and argued for a harmony of religions,” Long said. “This message is still desperately needed as religion continues to be used as a way to divide humanity against itself and to justify violence.”

Though he died shy of his 40th birthday in 1902, Vivekananda’s legacy in the Indian subcontinent and across the world endures more than a century later, Long said, highlighting the “many scholars and artists who found inspiration in his teachings: writers like Christopher Isherwood, Aldous Huxley and J.D. Salinger; scholars like Joseph Campbell, whose work inspired George Lucas to create the “Star Wars” films, which contain echoes of Swami Vivekananda’s thoughts in the teachings of the Jedi; and musicians like George Harrison, who read Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga early on in his own journey, and who himself inspired millions to look into Indian philosophy and meditative practice.”

Long added that despite this influence, Vivekananda is still largely unknown to many, especially in the internet age.

“I would say that Swami Vivekananda’s full impact on the world has yet to be fully felt and appreciated,” he said.

Murali Balaji. Photo via University of Pennsylvania

Organizers of the symposium hope they can help teach a new generation of learners about the legendary monk’s impact. For more information and to register for the symposium, visit the Free Library’s symposium page.

(Murali Balaji is a journalist and a lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the editor of “Digital Hinduism” and author of “The Professor and the Pupil,” a political biography of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

STRAY REMARKS ON THEOSOPHY

(Found among Swami Vivekananda's papers.)

The Theosophists are having a jubilee time of it this year, and several press-notices are before us of their goings and doings for the last twenty-five years.

Nobody has a right now to say that the Hindus are not liberal to a fault. A coterie of young Hindus has been found to welcome even this graft of American Spiritualism, with its panoply of taps and raps and hitting back and forth with Mahâtmic pellets.

The Theosophists claim to possess the original divine knowledge of the universe. We are glad to learn of it, and gladder still that they mean to keep it rigorously a secret. Woe unto us, poor mortals, and Hindus at that, if all this is at once let out on us! Modern Theosophy is Mrs. Besant. Blavatskism and Olcottism seem to have taken a back seat. Mrs. Besant means well at least — and nobody can deny her perseverance and zeal.

There are, of course, carping critics. We on our part see nothing but good in Theosophy — good in what is directly beneficial, good in what is pernicious, as they say, indirectly good as we say — the intimate geographical knowledge of various heavens, and other places, and the denizens thereof; and the dexterous finger work on the visible plane accompanying ghostly communications to live Theosophists — all told. For Theosophy is the best serum we know of, whose injection never fails to develop the queer moths finding lodgment in some brains attempting to pass muster as sound.

We have no wish to disparage the good work of the Theosophical or any other society. Yet exaggeration has been in the past the bane of our race and if the several articles on the work of the Theosophical Society that appeared in the Advocate of Lucknow be taken as the temperamental gauge of Lucknow, we are sorry for those it represents, to say the least; foolish depreciation is surely vicious, but fulsome praise is equally loathsome.

This Indian grafting of American Spiritualism — with only a few Sanskrit words taking the place of spiritualistic jargon — Mahâtmâ missiles taking the place of ghostly raps and taps, and Mahatmic inspiration that of obsession by ghosts.

We cannot attribute a knowledge of all this to the writer of the articles in the Advocate, but he must not confound himself and his Theosophists with the great Hindu nation, the majority of whom have clearly seen through the Theosophical phenomena from the start and, following the great Swami Dayânanda Sarasvati who took away his patronage from Blavatskism the moment he found it out, have held themselves aloof.

Again, whatever be the predilection of the writer in question, the Hindus have enough of religious teaching and teachers amidst themselves even in this Kali Yuga, and they do not stand in need of dead ghosts of Russians and Americans.

The articles in question are libels on the Hindus and their religion. We Hindus — let the writer, like that of the articles referred to, know once for all — have no need nor desire to import religion from the West. Sufficient has been the degradation of importing almost everything else.

The importation in the case of religion should be mostly on the side of the West, we are sure, and our work has been all along in that line. The only help the religion of the Hindus got from the Theosophists in the West was not a ready field, but years of uphill work, necessitated by Theosophical sleight-of-hand methods. The writer ought to have known that the Theosophists wanted to crawl into the heart of Western Society, catching on to the skirts of scholars like Max Müller and poets like Edwin Arnold, all the same denouncing these very men and posing as the only receptacles of universal wisdom. And one heaves a sigh of relief that this wonderful wisdom is kept a secret. Indian thought, charlatanry, and mango-growing fakirism had all become identified in the minds of educated people in the West, and this was all the help rendered to Hindu religion by the Theosophists.

The great immediate visible good effect of Theosophy in every country, so far as we can see, is to separate, like Prof. Koch's injections into the lungs of consumptives, the healthy, spiritual, active, and patriotic from the charlatans, the morbids, and the degenerates posing as spiritual beings.

Complete Works - Index - Volumes (ramakrishnavivekananda.info)

Swami Vivekananda’s Philosophy Of Yoga And Its Prevalence In Crowley’s Thelema

by Lani Milbus

This piece is an excerpt from Lani Milbus’ forthcoming book Effing the Ineffable.

The kind of person who would open a book such as this, a seeker, is usually someone who has a question about the nature of existence. More specifically, we want to know; what is the cause of suffering?

One does not come to these philosophical questions until there is a problem one wishes to overcome. That suffering is what gets the mind moving. We suffer from thirst; so, we begin to think about where to find water. In the same way, we live long enough to begin to question why we have to suffer through fear, insecurity, loss, pain and all of the things that appear to separate us from bliss.

I recall one such awakening that happened when I was about nine years old. There appeared, in the mind, a sudden awareness of the inevitability of the death of the body. I felt terrified. It caused the mind to apply this knowledge to my mother and all those whom I loved and depended upon. I asked my mother about what this meant. Her response was to reassure me that we all go to heaven when we die, establishing a comfort in the continuity of existence beyond death. While this consoled that 9-year-old child, that comfort came and went like the seasons until I broke down all of the barriers to understanding within the faculties of my being.

I have a very stubbornly skeptical mind. To break down barriers to realization would require me to answer for every contradicting philosophy within all of the religions, atheism, material science and everything. I was not satisfied with any explanation that only held my fancy in limited aspects. I needed an answer that encompassed all that exists or could ever exist. I needed to experience, not pontificate, speak nor hear about, but to actually experience for myself, the infinite.

It turns out that I am not alone in this insistence.

Swami Vivekananda and Gnana Yoga

While the masses argue about which God is real, or even if God is unreal, it turns out that a philosophical proof to settle this conflict has existed and already withstood at least 1600 years of attacks. It is called the Mandukya Karikas and contains the Mandukya Upanishad. The problem arising from the solution is that these 12 verses of the Upanishad are so perfectly simple and sublime; yet, they defy our most common conception of the nature of Self. So, it requires a profound paradigm shift to get beyond a superficial understanding of its claim to the point of experiential realization.

Swami Vivekananda, a Vedantic monk who lived at the turn of the 19th Century and is known as the modern father of Raja Yoga, described the path to enlightenment with an analogy of the flight of a bird. He said, “gnana yoga is one wing of the bird and bhakti is the other. Raja yoga is the tail that keeps the balance.” Vivekananda only partially elucidated the meaning of this analogy, perhaps assuming that those who would hear it were already accomplished yogis. Or, perhaps, he wanted to save the beauty of full realization for his audience to discover on their own. 120 years later, the analogy is at risk of obscurity, so I will elaborate.

Gnana means “knowledge,” so gnana yoga means “union (esp ‘union with God’) through knowledge.” There is a profound relationship between gnana yoga and bhakti yoga, translated as “union with God through devotion,” as opposing wings of our bird. The bird cannot perform its function, flight, without both wings. What Vivekananda did not provide in the analogy was the quality of attainment for each of these yogas. Therein lies the paradox we will need to carry over into enlightenment. This paradox is the contraindication between the attainments of gnana and bhakti, respectively.

In gnana yoga, one attains to the truth of the Mandukya Upanishad. If God is infinite and all-pervasive, God cannot be divided and must be omnipresent. If God is omnipresent, there is no part of me, or the world that I experience, that is not-God. I, and my experience, are all that I can ever truly know; therefore, I am one with God. Or, as is found in the Bible, “I Am That I Am.” This is the yoga of gnana, or knowledge.” It is called Advaita, in Sanskrit, meaning “not two.” This seems easy enough to conceptualize, but we need to be able to do more than just talk about “all is one….I am one with God.” Repeating the words is not realization. Realization comes when our every experience after realization is seen in this light.

Another Swami, Sarvapriyananda, put it plainly: “enlightenment never becomes a memory.” It changes the way we experience the world. To truly realize advaita, we have to dispel the ignorance of division, of a “this” and a “that.” There is only “I.” As Jesus Christ said, “I and my Father are one.” Aleister Crowley again says, “I am alone; there is no god where I Am.” This Upanishad says, “Tat Tvam Asi (That thou Art).

This is the revelation that all objects are false and that only pure subject exists. This is Brahman, the supreme reality. It is the one essence of every religion. Brahman, existence/consciousness/bliss, alone exists, nay is existence itself. All else is appearance, called maya (space/time/causation), whose essence is ignorance. Maya is ignorance itself as Brahman is consciousness/awareness itself.

You might ask, “but are these not two?” They are not. Ignorance is not really anything. It can be removed. And when ignorance is removed, all that remains is awareness, Brahman. This is the summit of gnana yoga. Now that we have our right wing flapping, why are we not flying?

Simply put, that which seeks enlightenment, the seeker, the bird, is just another appearance in maya. Anything that can be known, any object, is of maya. So, for the seeker to pronounce “I am God and it is finished” did not make the appearance disappear. You are still reading just as I am still writing. I still appear as this body and you still appear as that body. The world is still going on in what appears as “outside.” Nothing has changed. But if I see all of this and still know, not believe but know, that the I of my consciousness, that Brahman which is my true Self beyond my body/mind and all division, is my true nature, there is a danger that I will just give up my life. I will resent the appearance of the body/mind and will not see any point in living. Within maya, ignoring karma does not make it go away. To take up this attitude is not actually enlightenment and will only increase my attachment to samsara and delay liberation. It makes me become even more lost within the appearances of maya.

So long as I am experiencing karma, the body mind and life that appear in experience, there is still work to be done. The enlightened person does this happily. They live life after enlightenment the same as they did before, only they know it is not the absolute reality. Just as a chess-player could physically move any piece in any direction on the chessboard without limitation, if that player wants to enjoy the experience of the game they do not do so: they will follow the rules and limitations of the game. In that way, the enlightened person does their human karma within maya and by the rules of maya because they, as they are identified as appearing with a body/mind, are subject to the power of maya.

It is a theory within yoga that the purpose of this apparent individuality is to realize our true nature over many lifetimes. In each life we decrease ignorance by burning up the karma that created the appearance of each life.

Alan Watts described this, as Brahman got bored being alone and without change, so Brahman created a universe within. In that universe, because Brahman is very good at things, Brahman began to walk about as the objects of the universe and became confused. In this confusion, Brahman then spent all possible lifetimes looking for Brahman.

The danger in gnana can be found here. Living out the karma within may can be confusing when one begins to realize the truth. It can feel frustrating to know “I am Brahman” and still feel very small and powerless in our waking experience. It can lead to depression, suicide and all sorts of entanglements. The most efficient way to navigate maya is to actually be the omnipresent, all pervading creator of this universe too. Within maya, that is God or whatever we refer to as our own highest ideal. The reason this is a paradox is that we know, from the perspective of ultimate reality that no god exists outside our true Self. But at the level of maya, we need God, or a highest ideal, to which to aspire and become. That is the business of bhakti yoga.

Again, bhakti means devotion, which is a kind of love. We love God through devotion of ritual, prayer, adoration, offering, service and any other way our chosen religion or spiritual path prescribes. Bhakti requires a deep commitment and passion. Whereas gnana yoga demands experience and shuns belief, bhakti requires faith. When an enlightened person practices bhakti, they do so with the knowledge that this is not the supreme reality. However, is as real as any other appearance including hunger, pain, sexual pleasure, thought or any experience that can be had in the body. It is every bit as real as those and, at the same time, not real at all. Loving God, contemplating God, serving God; these are the flapping of the left wing. The bird flies only when these opposites are both working together.

Vivekananda and Raja Yoga

Swami Vivekananda called raja yoga “the tail.” Raja yoga is a series of methods for using the body/mind to overcome the body/mind. The paradox is extremely difficult to maintain as a perspective on reality while the aspirant is identifying the body/mind as self. The mind cannot grasp ideas about pure unchanging consciousness that are beyond mind. Mind thinks of itself as the source of consciousness, “I think therefore I am.” Raja yoga eventually subjugates, mind, body, ego and all of the faculties for experiencing consciousness to consciousness itself. The attainment of raja yoga is samadhi. Raja is loosely translated as “the highest” and raja yoga unites the gross and subtle, which enables, through a purification of the gross, for one to balance the paradox of gnana and bhakti. Since there is only one more yoga in Vivekananda’s philosophy, I will mention it here. It is called karma yoga and it is yoga through action. Karma yoga is like the actual flight of the bird. In karma yoga, our deeds, our thoughts our very life is meant to unite us with the ideal. In other words, the bird flies to its destination instead of aimlessly wandering through maya.

The European iteration of this philosophy, which is a thorough examination into the true nature of Self and the aligning of all that we do we do with the quality of that nature, was presented by Aleister Crowley in the early twentieth century. He imbedded Vivekananda’s philosophy of yoga into his own spiritual system, called A:.A:. In fact, the first order of this system manifests Vivekananda’s “bird” within its grades.

If one were familiar with the grades of this system and their corresponding positions upon the Qabalistic Tree of Life, a superimposition of this bird can be seen when the various yogas are viewed according to the grades in which the three yogas are prescribed. Raja yoga is focused in the first two grades on the middle pillar, while bhakti and yoga are in the right and left pillars, respectively, formulating the wings.

Crowley stated the accomplishment of these attainments, knowledge of Self and performing actions in accordance with that true nature, as the central law of his Philosophy, “Do what thou Wilt,” derived from the word “Thelema,” which in Greek translates as an expression of inevitability similar to the English, “It is God’s will.” Crowley simply translated Thelema to mean “Will,” with a capital “W” to differentiate it from desire or whim.

First, the mind and body are purified in order to deal with the required paradigm shift that is knowledge of our true identity as atman/Brahman. Only after these two, can we make choices for action that are in harmony with out True Will. That is the point of Thelema and Vivekananda’s philosophy of yoga.

No comments:

Post a Comment