Guatemala

Seven Decades After Guatemala Coup, Bernardo Arévalo Sees a Dramatic Rise

The son of Guatemala’s first democratically-elected president, almost 70 years after that experiment was crushed by a coup, takes up the banner of democratic change as his country again slips toward autocracy. He goes from polling at 0.7% to somehow making the runoff for president.

No, it’s not the opening to a Gabriel García Márquez novel; it’s what happened in Guatemala on Sunday. Bernardo Arévalo, the candidate of the fledgling center-left Semilla party and son of ex-president Juan José Arevalo (1945-51), came out of nowhere to finish second in a crowded first-round vote for president. No one saw it coming—not even the leaders of Semilla.

And now many Guatemalans, and the rest of the world, are asking: Who is Bernardo Arévalo, and can he actually win a runoff on August 20 despite opposition from most of the country’s political and economic elites?

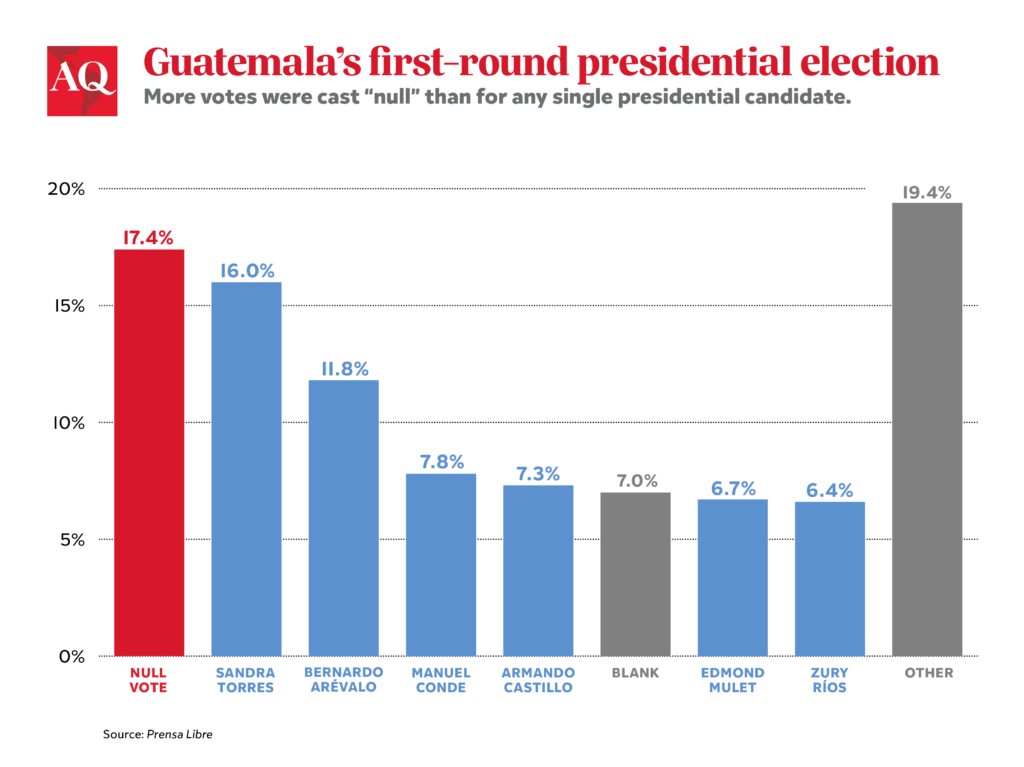

To get here, Arévalo depended on context as much as his campaign: Guatemala’s electoral tribunal sidelined three popular presidential candidates, all of whom criticized government corruption. That left only opposition candidates with vanishingly low poll numbers, like Arévalo, in the race. Nearly one in six voters, fed up with Guatemala’s self-serving political system and failing state institutions, spoiled or left blank their ballots. Another 12.25% broke for Arévalo. Given a fragmented electorate, it was enough to put him into the runoff.

Arévalo will face the conservative and establishment favorite Sandra Torres, who finished first with 15.78%. To win, Semilla, a relatively young party, will have to outcompete Torres’ nationwide network of seasoned political operators. And if Guatemala’s present is anything like its past—Arévalo’s surname suggests as much—then he will face an uphill battle that will show how much, or how little, Guatemalan politics has really changed.

Popular, but not populist

Obscure outsiders who sweep up vote last-minute are becoming a dime a dozen in Latin America. Just think of Peru’s Pedro Castillo or Colombia’s Rodolfo Hernández.

Arévalo, too, is an outsider. Before entering Congress with Semilla in 2020, he had never participated in politics, building a career as a diplomat, sociologist and NGO worker instead. Given his father’s truncated political career and long post-coup exile, Arévalo did not inherit a political family dynasty.

Arévalo senior, a schoolteacher exiled to Argentina, became Guatemala’s first democratically-elected president in 1945 after the ouster of longtime dictator Jorge Ubico by a mass citizen’s movement. He oversaw popular constitutional and social reforms that his successor, Jacobo Árbenz, continued. Árbenz also attempted a land reform, but he was overthrown by a 1954 CIA-orchestrated coup, which opened the door for decades of military rule. Arévalo senior spent decades in exile, and his son maintained a low profile after returning to Guatemala at age 15 to study.

Now, though an outsider, Arévalo is no populist, unlike Castillo or Hernández. His campaign-trail interviews are almost painfully devoid of punchy slogans. Semilla’s policy-heavy platform—entitled, “for a livable country”—gives you a sense of the scope of Arévalo’s ambitions: pragmatic, not utopian. Since first entering congress with seven representatives—a number that shrank to six after one MP was expelled for violating the party’s strict code of ethics—Semilla leaders have spent more time documenting and denouncing government corruption than churning out TikTok videos.

Even so, the election results suggest Arévalo and Semilla made inroads—not only in Guatemala City, where the party retains a middle-class base, but also among a more socioeconomically diverse set of voters in the capital’s sprawling suburbs and urban centers across the country.

A centrist reform agenda

Arévalo decided to enter politics, and helped found Semilla, in the wake of the 2015 mass anti-corruption protests known as the “Guatemalan spring,” which ousted ex-president Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti from office for orchestrating a vast graft scheme (both are now serving jail time). When the next president, an outsider named Jimmy Morales, defanged anti-corruption institutions instead of strengthening them, as he had promised, Arévalo says he knew it was time to construct the “real alternative” Guatemalans lacked. In 2019, Semilla’s candidate for the presidency, ex-Attorney General Thelma Aldana, was polling in the lead—until she was disqualified by the TSE and death threats forced her to flee the country.

Arévalo and Semilla are centrists—but in a country where politics habitually skews right, they are often described as center-left. “Semilla has a social democratic element, but its program is centrist, and it also has some center-right followers,” said Lucas Perelló, a political scientist who has spent time studying the party’s formation. Arévalo says he wants to gradually universalize existing social assistance programs to include a greater share of poor Guatemalans, reduce the cost of medicines and healthcare, and link isolated parts of the country through new infrastructure—doable tasks, given Guatemala’s exceptionally low share of debt as GDP, and necessary ones, given the country’s soaring poverty and malnutrition rates.

On security issues, another major concern for Guatemalans, Arévalo promises to increase state presence in crime hotspots, reclaim jails from gangs, and use intelligence-gathering to dismantle mafias. He says Bukele’s anti-gang strategy is not applicable to Guatemala. He is also critical of human rights abuses in Venezuela and Nicaragua and Putin’s war on Ukraine and has no stated plans to recognize China over Taiwan. Asked for a leader he admires, he named the ex-president, José Pepe Mujica, of Uruguay, where he was born during his father’s exile.

But Arévalo says his first order of business will be confronting corruption—the stumbling block in the way of all other issues. Instead of punitive justice, Arévalo emphasizes cutting pork-barrel spending from the national budget and reducing cost overruns in public works. That would generate resistance from a congress set to be controlled largely by establishment parties, where Semilla will hold 24 of 160 seats—but Arévalo says he would rather achieve a part of his agenda using executive authority rather than all of it via pacts with politicians implicated in corruption.

The path ahead

The received wisdom in Guatemalan politics is that anyone can beat Sandra Torres in a runoff. Although she scooped up 15.7 percent of the vote on her first-round run, the ceiling on her support is low: a full 41.3 percent of Guatemalans say they would never vote for Torres, seen by many as a shapeshifting opportunist. Her biggest strength, and weakness, is that she commands a vast political machine—capable of delivering votes in her rural strongholds, but also likely to alienate many Guatemalans fed up with corrupt politics-as-usual. In 2015 and 2019, she lost runoffs to conservative competitors by large margin.

This time, dynamics could be different. Arévalo, unlike the last two candidates to challenge Torres, is not interested in cutting deals with the establishment. He’s already promised to bring in exiled anti-corruption prosecutors and judges as advisors on anti-corruption should he win office—a pledge sure to terrify many Guatemalan elites, who could swiftly align behind the more malleable Torres.

Still, elite support could be more of a liability than a boon, given widespread anti-establishment fervor. Between now and August, Arévalo’s biggest challenge will be convincing some of the one in six voters who spoiled or left blank their ballots that they should bet on him and Semilla, instead. He will also likely need to overcome a narrative by elite-owned media that he and his co-partisans are disguised communists or George Soros’ apparatchiks.

“1985… 1996… 2015,” reads Semilla’s platform, ticking off pivotal years when Guatemala established democracy, ended its internal armed conflict, and ousted a corrupt president and vice president. Now, 2023 just might shape up to be the next pivotal year in Guatemalan history.

No comments:

Post a Comment