As soon as Nelson Mandela was released from prison after 27 years, in still apartheid South Africa, U.K. officials lobbied him for business interests, declassified files show, reports Mark Curtis.

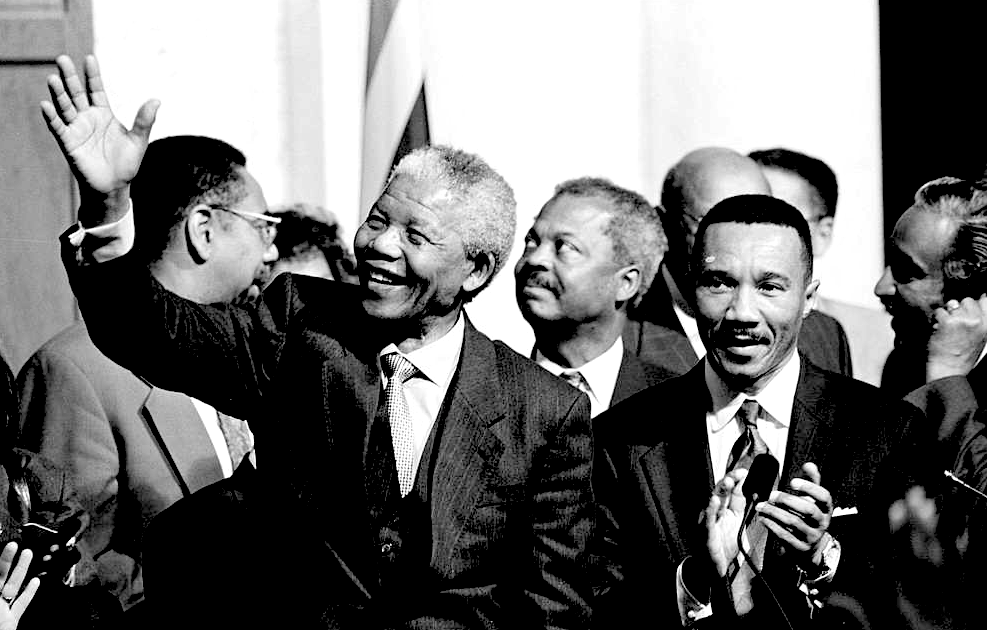

South African President Nelson Mandela with members of the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus including Representative Kweisi Mfume, on right, 1994. (Maureen Keating, Library of Congress)

By Mark Curtis

Declassified UK

June 6, 2023

British officials feared Nelson Mandela would nationalise South Africa’s economy and lobbied him to protect British commercial interests as soon as he gained freedom.

The U.K.’s Foreign Office set out to “educate” the African leader with “sensible” economic policies and to counter “the absurdity of nationalization,” declassified files show.

British fears were sparked one month before Mandela’s release from jail.

On January 15, 1990 Mandela issued a statement saying nationalising “the mines, banks and monopoly industries” was the policy of the African National Congress (ANC) — of which he was then deputy president — and that a change in this view was “inconceivable.”

He added that “Black economic empowerment is a goal we fully support and encourage, but in our situation state control of certain sectors of the economy is unavoidable.”

At the time, British firms in South Africa accounted for no less than half of all foreign investment in the country. Prominent among the U.K. companies were the banks NatWest, Barclays and Standard Chartered, which were all subject to lawsuits for complicity in apartheid after the regime fell.

British mining companies Anglo American and De Beers also faced legal claims for exploiting black workers.

Britain had maintained and profited from these investments under decades of apartheid, with Margaret Thatcher’s government famously opposing sanctions, and had no desire to see them disappear with an ANC-led government.

‘Absurdity of Nationalisation’

British officials feared Nelson Mandela would nationalise South Africa’s economy and lobbied him to protect British commercial interests as soon as he gained freedom.

The U.K.’s Foreign Office set out to “educate” the African leader with “sensible” economic policies and to counter “the absurdity of nationalization,” declassified files show.

British fears were sparked one month before Mandela’s release from jail.

On January 15, 1990 Mandela issued a statement saying nationalising “the mines, banks and monopoly industries” was the policy of the African National Congress (ANC) — of which he was then deputy president — and that a change in this view was “inconceivable.”

He added that “Black economic empowerment is a goal we fully support and encourage, but in our situation state control of certain sectors of the economy is unavoidable.”

At the time, British firms in South Africa accounted for no less than half of all foreign investment in the country. Prominent among the U.K. companies were the banks NatWest, Barclays and Standard Chartered, which were all subject to lawsuits for complicity in apartheid after the regime fell.

British mining companies Anglo American and De Beers also faced legal claims for exploiting black workers.

Britain had maintained and profited from these investments under decades of apartheid, with Margaret Thatcher’s government famously opposing sanctions, and had no desire to see them disappear with an ANC-led government.

‘Absurdity of Nationalisation’

New arrivals at the Crossroads Squatters Camp near Cape Town, South Africa, circa 1980. Many black South Africans, searching for work and unable to find homes in the townships, or unwilling to live separated from their families in all-male hostels there, became squatters, living under constant threat of forced removal. (UN Photo/DB)

Britain’s ambassador in Pretoria, Robin Renwick, wrote in June 1990 that the South African state already held large holdings in many companies but that “the idea that nationalising the banks, mines and ‘monopoly industry’ can help to redistribute wealth has proved a short cut to disaster wherever it has been tried.”

Ahead of Mandela’s first visit to the U.K. in July 1990, just five months after his release, the Foreign Office prepared a brief stating that a key U.K. objective was to “encourage recognition” of “sensible economic policies which encourage investment.”

“There are some signs that economic realities are beginning to impinge” on Mandela, “with less talk of wholesale nationalisation but the process of education will take time,” Stephen Wall, private secretary to Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd, wrote.

“Nationalisation is not the answer,” Wall added in his brief. South Africa needed “economic policies to foster growth and attract investment.”

When Hurd met Mandela on July 3, he asked the South African if his economic policies “included nationalization.” Mandela replied that state ownership in his country was “nothing new” and that “the problem was an unfair distribution of resources.”

Ahead of Thatcher’s meeting with Mandela, Charles Powell, the prime minister’s private secretary, was even starker in his brief for his boss. “The absurdity of nationalisation” was one of the main issues he advised Thatcher to raise.

‘Troubled’

U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the U.S., 1981. (U.S. National Archives)

Thatcher met Mandela for the first time in person in Downing Street on July 4, 1990.

According to the British notes of the meeting: “The prime minister said that she was troubled by the emphasis given in Mandela’s remarks since his release to negative aspects such as sanctions, armed struggle and nationalization.”

Thatcher “stressed the importance of an open economy, in order to attract investment and create growth.”

Mandela told her that “state participation in industry was an option, but only one.” … “He wanted to stress that the ANC had not decided on nationalisation: they hoped that viable alternatives could be found.”

But he also told Thatcher that “virtually all the resources of South Africa were owned by a tiny minority of the white minority.” He added that “the great mass of black people were experiencing poverty, hunger, illiteracy and unemployment.”

“Unless this inequitable distribution could be rectified, it would not be possible to get democracy to function.”

Redistribution

The day before Thatcher met Mandela, the Foreign Office had told her that nationalisation “was clearly receding as an issue” and that Mandela was rather concerned with “the unfair distribution of resources.”

This was also what Ambassador Renwick had told London after meeting Mandela the previous month.

He said the ANC would not nationalise “anything” when in power and that all the major utilities were already in the public sector. The “key issue” for Mandela, Renwick wrote, “was not nationalisation but the distribution of wealth.”

Jan. 1, 1982: Inhabitants of Ekuvukene, a “resettlement” village in the black “homeland” called KwaZulu in Natal. Millions of black South Africans were forcibly moved to such villages over the previous 30 years. They had become dumping grounds for women and children, the sick and the elderly, and anyone else deemed unnecessary to the white economy. (UN Photo)

“South Africa could not go on with a situation in which whites owned 87% of the land,” Renwick wrote, expressing Mandela’s view.

After Thatcher resigned in November 1990, Mandela held his first meeting with new Prime Minister John Major in London in April 1991.

The notes of the meeting, held in Downing Street, record that Mandela “favoured a mixed economy with public and private ownership and cooperatives.”

Officials were still not entirely reassured, however.

Wall, who was by now Major’s private secretary, wrote that Mandela “has a remarkable lack of bitterness but his view of the world is coloured by the fact that when he went to prison Britain was still a colonial power and intervention economics were fashionable.”

The Foreign Office noted at the time that the South African economy was in recession the previous year, that unemployment was on a “massive scale” — and at over 50 percent in the townships – and that 84 percent of the rural population lived below the poverty line.

It added that there was “uncertainty about ANC economic policies” and that “they have moved a long way from calls for nationalisation but still hanker after a command economy.”

Change of Stance

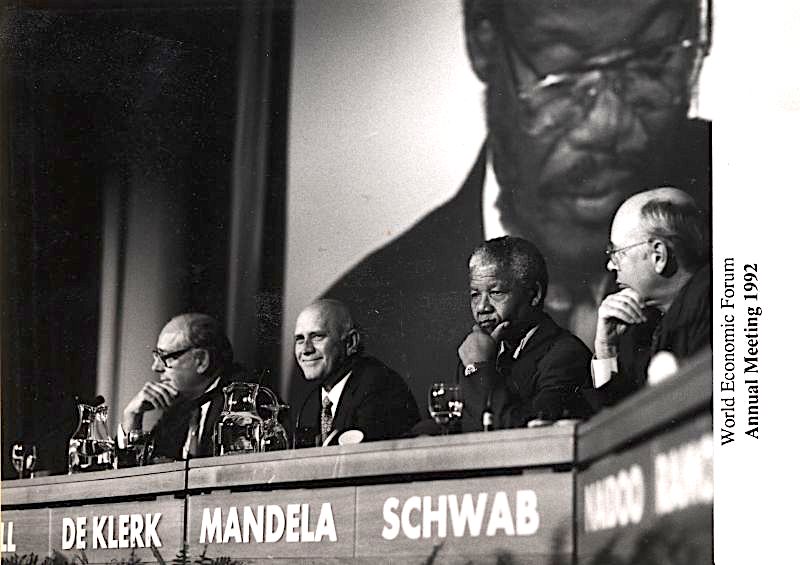

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 1992. From second to left: Frederik de Klerk, Nelson Mandela, Klaus Schwab. (World Economic Forum. Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As debates on nationalisation in the ANC continued, Mandela’s unequivocal change of stance on the issue has been pinpointed to January 1992 during a trip to Davos, Switzerland, for the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum.

Mandela said of his conversations there with other world leaders: “They changed my views altogether. I came home to say: ‘Chaps, we have to choose. We either keep nationalisation and get no investment, or we modify our own attitude and get investment.’ ”

By May 1993, Mandela visited Major again in London “to encourage foreign investment,” the notes of that meeting state.

He reassured British officials that “the ANC’s economic policies had been modified, particularly regarding nationalisation, and now offered an inviting climate for foreign investment.”

Major reiterated: “He wished to see investment in South Africa: there was substantial interest on the part of U.K. companies in returning.”

Five months later, in October 1993 Mandela gave a speech at the Confederation of British Industry in London “calling for British companies to invest in a climate of sound economic policies,” the Foreign Office noted.

There were by now other advantages to South Africa’s economic openness. The Foreign Office wrote that “there are now no restrictions on defence sales to South Africa” and that “prospects are good for BAE’s Hawk and for naval frigates from Swan Hunter.”

“We are already the biggest foreign investor in South Africa; we hope to build on this position,” the Foreign Office said in another memo.

The U.K. remains a major investor in South Africa, amounting to over £20 billion worth. South Africa’s mineral riches still lie substantially in the hands of British companies, with huge investments in its gold, platinum, diamonds and coal.

‘Too Democratic’

The files also contain some of the British officials’ views on Mandela. Renwick wrote in June 1990 that he “has a natural dignity and authority” but “is not as intelligent as [Zimbabwean leader Robert] Mugabe, but a great deal nicer.”

A U.K. brief on Mandela the following year described him as “rather old-fashioned and rather wooden in manner and a poor public speaker who nevertheless picks his words skillfully.”

He was also “on the nationalist/Africanist wing of the ANC — loyal to, but much more moderate than, overtly socialist/SACP [South African Communist Party] elements.”

Wall wrote in April 1991 that “Mandela has enormous dignity and has borne considerable hardship with great resilience. His mind is not closed to fresh ideas but he can be obstinate and… his organisation is if anything too democratic.”

Mark Curtis is the editor of Declassified U.K., and the author of five books and many articles on U.K. foreign policy.

This article is from Declassified UK.

No comments:

Post a Comment