CBC

Sun, July 23, 2023

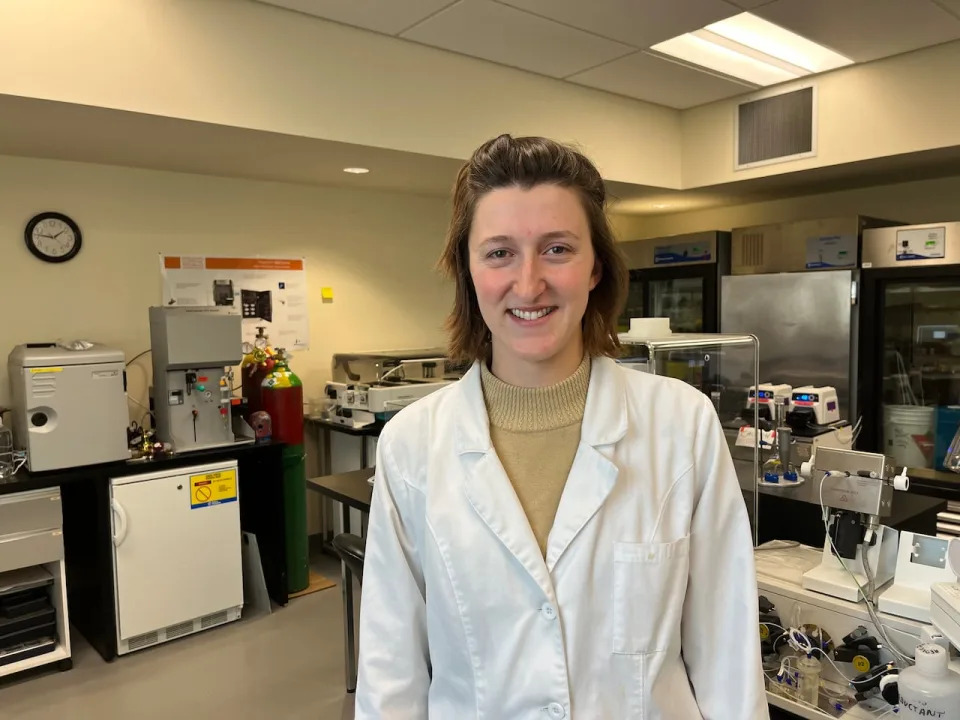

Taylor Belansky, a research student at Yukon University, is studying how to support the growth of bacteria that converts nitrate, often found at mine sites, into nitrogen.

(Lilian Fridfinnson/CBC - image credit)

The battle to manage the invasion of nuisance plants in the North is ongoing, but one Yukon University master's student may have found a purpose for some pesky and resilient weeds.

Taylor Belansky, with the university's Northern Mine Remediation team, studies how to mitigate the environmental impacts of mining. Her thesis research aims to find a way to support the growth of bacteria that converts nitrate, often found at mine sites, into nitrogen.

She says feeding that bacteria is one way to filter mine-impacted water. With the support of her research advisor, Guillaume Nielsen, Belansky tested carbon sources including wood chips, compost, grains from Yukon Brewing, molasses and invasive plants such as foxtail barley and white sweet clover. The student researcher was amazed by the results, finding white sweet clover, a usually undesired weed, was the most effective food source.

"It's really cool that we tried it because the white sweet clover is readily found at mine sites," she said. "Nature has the answer to these contaminants that we're putting into the environment. We just have to find out how best to help those natural processes along."

Belansky says mine blasts often results in incomplete combustion of blasting fuel, leaving behind high concentrations of nitrate residue that can leech into waterways and harm aquatic ecosystems. A process called eutrophication causes algae blooms and poses a risk to the health of fish, as it can suffocate them.

"Nitrate is naturally occurring. The poison is in the dose. So, nitrate is naturally out there, but when it's in low concentrations, the plants are using it," Belansky explained. "It's when we're putting in too much that it overwhelms the system, especially aquatics systems."

Sweet clover is the most common invasive plant species in the Yukon.

Sweet clover is the most common invasive plant species in the Yukon. Belansky found it was also the most effective food source for the nitrogen-creating bacteria. (

The battle to manage the invasion of nuisance plants in the North is ongoing, but one Yukon University master's student may have found a purpose for some pesky and resilient weeds.

Taylor Belansky, with the university's Northern Mine Remediation team, studies how to mitigate the environmental impacts of mining. Her thesis research aims to find a way to support the growth of bacteria that converts nitrate, often found at mine sites, into nitrogen.

She says feeding that bacteria is one way to filter mine-impacted water. With the support of her research advisor, Guillaume Nielsen, Belansky tested carbon sources including wood chips, compost, grains from Yukon Brewing, molasses and invasive plants such as foxtail barley and white sweet clover. The student researcher was amazed by the results, finding white sweet clover, a usually undesired weed, was the most effective food source.

"It's really cool that we tried it because the white sweet clover is readily found at mine sites," she said. "Nature has the answer to these contaminants that we're putting into the environment. We just have to find out how best to help those natural processes along."

Belansky says mine blasts often results in incomplete combustion of blasting fuel, leaving behind high concentrations of nitrate residue that can leech into waterways and harm aquatic ecosystems. A process called eutrophication causes algae blooms and poses a risk to the health of fish, as it can suffocate them.

"Nitrate is naturally occurring. The poison is in the dose. So, nitrate is naturally out there, but when it's in low concentrations, the plants are using it," Belansky explained. "It's when we're putting in too much that it overwhelms the system, especially aquatics systems."

Sweet clover is the most common invasive plant species in the Yukon.

Sweet clover is the most common invasive plant species in the Yukon. Belansky found it was also the most effective food source for the nitrogen-creating bacteria. (

Yukon Invasive Species Council)

Lori Fox, the summer outreach coordinator with the Yukon Invasive Species Council, says white sweet clover is unyielding, popping up through soil and gravel to colonize. Initially transported to the Yukon for agriculture purposes, Fox says it chokes out native plant species due to its nitrogen-fixing nature, as many of Yukon's native plants prefer a lower-nitrogen environment.

"It wasn't originally supposed to escape," Fox said during an interview with CBC's Yukon Morning host, Elyn Jones. "But like many invasive species, it did and you see it all over the place."

The issue with sweet clover and other invasive species is that they alter biodiversity and change where animals can find their food, says Fox.

"It has the potential to really alter the landscape," Fox said. "Even if we can't stop what is in place…in many cases that's impossible, we have a responsibility to mitigate."

Tyler Obediah, natural resource coordinator with Carcross/Tagish First Nation, says the changing landscape is illustrated by decreasing fireweed populations.

Lori Fox, the summer outreach coordinator with the Yukon Invasive Species Council, says white sweet clover is unyielding, popping up through soil and gravel to colonize. Initially transported to the Yukon for agriculture purposes, Fox says it chokes out native plant species due to its nitrogen-fixing nature, as many of Yukon's native plants prefer a lower-nitrogen environment.

"It wasn't originally supposed to escape," Fox said during an interview with CBC's Yukon Morning host, Elyn Jones. "But like many invasive species, it did and you see it all over the place."

The issue with sweet clover and other invasive species is that they alter biodiversity and change where animals can find their food, says Fox.

"It has the potential to really alter the landscape," Fox said. "Even if we can't stop what is in place…in many cases that's impossible, we have a responsibility to mitigate."

Tyler Obediah, natural resource coordinator with Carcross/Tagish First Nation, says the changing landscape is illustrated by decreasing fireweed populations.

Fireweed in the Yukon.

Fireweed is being crowded out by sweet clover in some parts of the Yukon. (Paul Tukker/CBC)

Fireweed is native to the North and used traditionally by First Nations communities as a food source for its richness in vitamins A and C. Obediah says the purple plant, often found in the same dusty and disturbed soil as white sweet clover, is often cooked in butter, eaten raw or pickled. Given its medicinal properties, fireweed is also often used to make salves, lotions, and tea.

"For a lot of First Nations it's important to maintain that relationship with the plants," he said. "It's a deep cultural connection to the earth and to everything that's around us. It's very important in a lot of ways."

Despite its myriad of uses, Obediah says fireweed is becoming increasingly difficult to find, as the white clover crowds out the native plant.

Tyler Obediah is the natural resource coordinator with Carcross/Tagish First Nation in the Yukon.

'For a lot of First Nations it's important to maintain that relationship with the plants,' said Tyler Obediah, natural resource coordinator with Carcross/Tagish First Nation. (Submitted by Tyler Obediah)

Given its unwelcome habitation, Belansky says she's pleased to find a purpose for the vexing weed.

"We're killing two birds with one stone here," she said. "We're not intentionally letting it grow. We don't want it to further invade the mine site. We actually want to remove it from the mine site and put it to use."

The next step in Belansky's research will take her findings outside the lab to the Minto mine site in central Yukon. She says she will use "bioreactors" — 55-gallon drums — to filter mine-impacted water and see how the bacteria, fed with white sweet clover, cope with changing water chemistry, conditions and temperatures.

Belansky expects to complete her research and publish her findings in December and is eager to see what her research yields.

"Knowing the impact mining has had on the environment, I just wanted to be a part of more solutions."

No comments:

Post a Comment