In this article, we look back at the birth of the homosexual movement in Germany, its ties to socialism, and the lessons of this alliance — in its victories and defeats.

Camille Lupo June 30, 2023

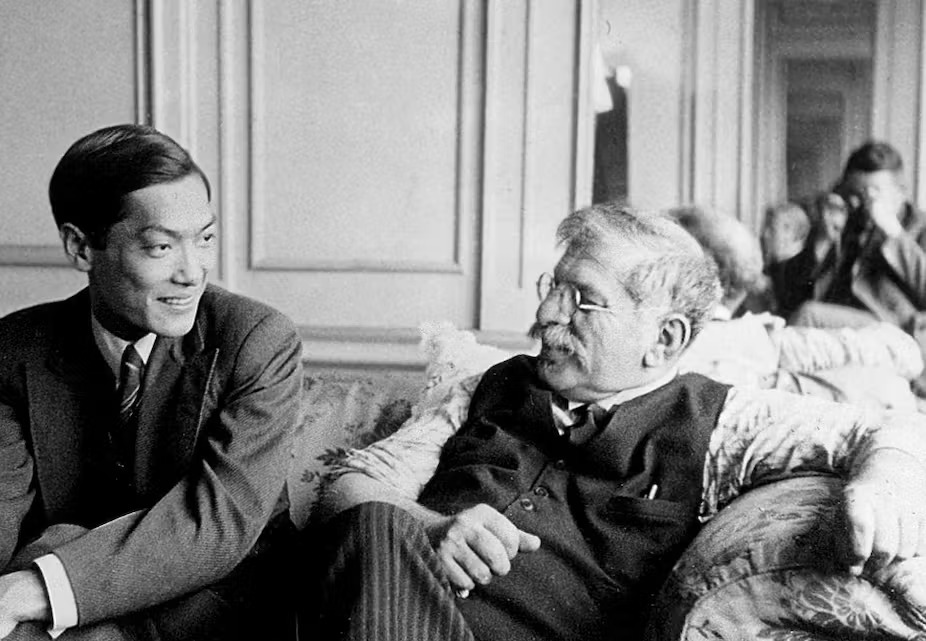

Magnus Hirschfeld (right) who was one of the first socialists to take up LGBTQ+ rights.

Although Marx and Engels had already mentioned homosexuality in some of their writings — as well as reflections on gender, sexuality, and the family — it was the demands and actions of organized revolutionaries during the first attacks on LGBTQ+ people across Europe that demonstrated the potential of the alliance between the LGBTQ+ movement and the revolutionary Left. Here we look back at the birth of the homosexual movement in Germany, its ties to socialism, and the lessons of this alliance — in its victories and defeats.

Although Marx and Engels had already mentioned homosexuality in some of their writings — as well as reflections on gender, sexuality, and the family — it was the demands and actions of organized revolutionaries during the first attacks on LGBTQ+ people across Europe that demonstrated the potential of the alliance between the LGBTQ+ movement and the revolutionary Left. Here we look back at the birth of the homosexual movement in Germany, its ties to socialism, and the lessons of this alliance — in its victories and defeats.

Precursors of the Homosexual Movement in Europe

In Sexuality and Socialism, Sherry Wolf paints a portrait of Edward Carpenter, one of the first openly gay men in the public eye. An influential English socialist in the 1870s, Carpenter had a background in the anarchist and utopian branches of English socialism. He wrote extensively on women’s emancipation and class society. At a time when homosexuality was illegal, Carpenter’s writings and public speeches linked the Victorian climate of sexual repression to an economic system based on competition. Dialoguing with his German predecessor Karl Ulrichs, Carpenter defended the idea that there exists within everyone a homosexual potential.

Ulrichs, a German jurist, is perhaps the most well-known forerunner of the homosexual movement. His work represents the largest collection of texts on homosexuality in the 1860s. In 1862, he published writings that first used the term uranian (Urning in German). The concept aimed to designate gay and lesbian people as a “third sex,” which he believed was defined by the presence of a female spirit in a male body for gay men, and vice versa for lesbians. While Ulrichs’s ideas may appear outdated today, and his conceptions are rooted in essentialist assumptions about gender and sexual orientation, suggesting they are psychologically and biologically predetermined, they nevertheless marked advancements for the time. His ideas remained influential for decades in the early stages of the homosexual movement in Germany and beyond, including England and the rest of the European continent, in no small part thanks to Ulrichs’s persistence. Despite public insults and even imprisonment, he was one of the first gay men to come out publicly, and he wrote for years against repressive laws targeting homosexual people.

Ulrichs maintained regular correspondence with Karl Maria Benkert, a German-speaking Hungarian writer known by the pseudonym Karoly Maria Kertbeny, who also moved in literary and philosophical circles influenced by Marx. He is credited with coining the term homosexual. In 1869 he wrote an open letter to the German minister of justice in defense of homosexual rights. Like Ulrichs, he expressed concerns that a Prussian law criminalizing male homosexuality (limited for the time being to that state, which was not yet unified with the rest of Germany) could become national. In his letter, he argued that the French Revolution and Napoleon’s Civil Code in France had already decriminalized homosexuality, and that such a law would be a step backward for Europe as a whole.

The core of his argument asserted that sexual freedom for homosexual people would not pose any problems to society at large since, according to the logic of Kertbeny his contemporaries, homosexuality is innate and natural, in contrast to the then-prevailing view that homosexuality is a “perversion.” His aim was to reassure the majority and conservative institutions by showing them that there would be no risk of homosexual “contagion.” This concern echoes in the moral panics and arguments of today’s queerphobic reactionaries. The second part of his argument sought to highlight the respectability of homosexual people throughout history. He provides a detailed list of historical and literary figures who were purportedly homosexual — from Shakespeare to certain kings of England — with the aim of discouraging the Ministry of Justice from locking up homosexual people.

This pressure to be “respectable,” as well as the desire to adopt a stance aimed at reassuring conservatives or reactionaries, is a theme that persisted throughout the early years of the homosexual movement. But the contributions of Kertbeny and Ulrichs also questioned the logic of “good morals.” Drawing on the state of research on sexuality at the time, they sought to demonstrate the scientific inconsistencies of bourgeois moral clichés. Kertbeny also pointed out one of the underlying functions behind the persecution of homosexual people: since this persecution was neither scientific nor natural, it must serve a social and political purpose — to create societal scapegoats.

While Germany witnessed the beginnings of what would become the theoretical foundations of homosexual activism, in England, the trial of Oscar Wilde unfolded, which would come to symbolize the persecution of gay men in Europe and catalyze the need for a movement for homosexual rights.

In Germany, in the journal of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), Eduard Bernstein published an article in defense of Wilde. As a leader and theorist of the SPD, Bernstein outlines in this lengthy two-part article, cited in The Early Homosexual Rights Movement by John Lauritsen and David Thorstad, a materialist critique of the sexual norms of the bourgeoisie and the moral framework that surrounds them. He explains his logic as follows:

Although the theme of sexual behavior may not be of paramount significance for the economic and political struggle of social-democracy, the search for an objective means of assessing this side of social life as well is not irrelevant. It is necessary to discard judgements based on more or less arbitrary moral concepts in favour of a point of view deriving from scientific experience. The Party is strong enough today to influence the shape of state law, its speakers and its press influence both public opinion and members and their contacts. Thus the Party already has a certain responsibility for what happens today. So an attempt will be made in the following to smooth the way towards such a scientific approach to the problem.

Throughout his article, Bernstein argues for a historical and social understanding of sexuality, in contrast to the absolute, idealistic, and psychiatric understanding used by conservatives, whom he describes as “reactionaries.” This position was unprecedented in society at the time, but it also represents the most advanced analysis of the intersection between sexuality and politics within the socialist movement of that period.

The Humanitarian-Scientific Committee

In 1871, the law that concerned Ulrichs and Kertbeny went into effect without any debate, enshrined in the Penal Code of the Second German Reich. Paragraph 175 criminalized “unnatural sexual acts,” effectively encompassing any sexual act between two men, as interpreted by legal precedent. When the law was passed even after Kertbeny’s letter and Ulrichs’s efforts, it took over 20 years for a genuine homosexual movement to finally emerge in Germany.

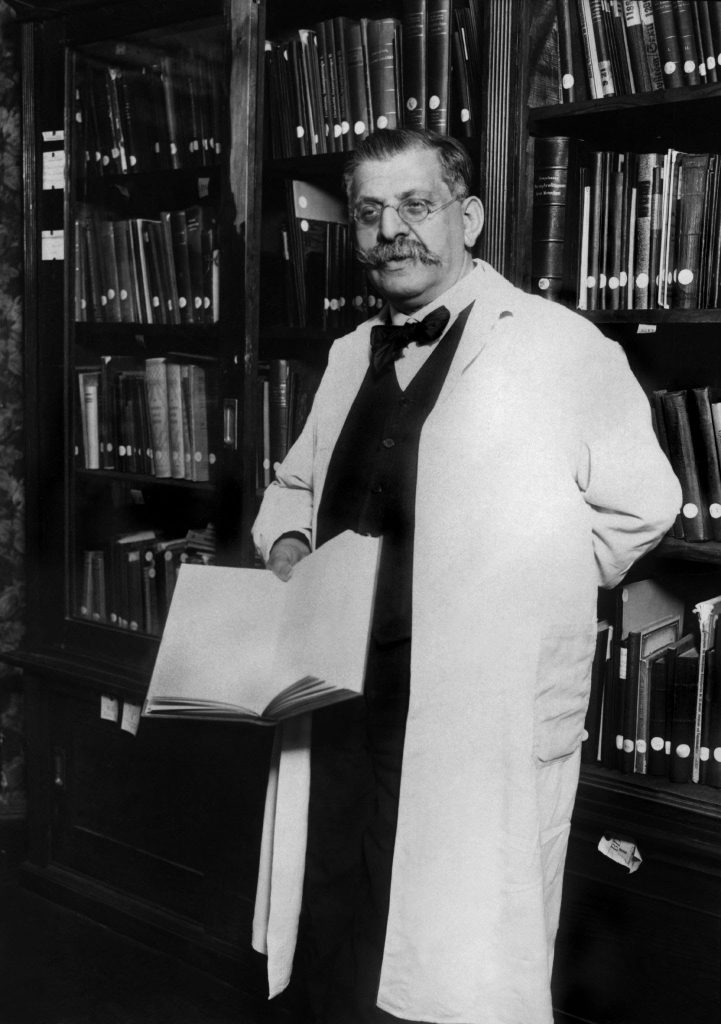

Two years after Ulrichs’s death, Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897. As a medical doctor and SPD member, he maintained correspondence with Wilde during his years in prison. He remained the committee’s leading figure throughout its 35 years of existence. In one of its early publications, the committee defined its goals as follows:

1. To persuade the legislative bodies to abolish the anti-homosexual paragraph of the German penal code, Paragraph 175;

2. To enlighten public opinion about homosexuality;

3. To engage homosexuals themselves in the struggle for their rights.

To achieve these goals, the committee’s work focused on influencing elected officials (through discussions, open letters, scientific literature, etc.) and spreading its ideas to the general public through conferences, public speeches (mainly conducted by Hirschfeld), and regular publication of magazines. The committee’s main activity, however, was a petition campaign over several years to collect signatures from influential figures against paragraph 175.

From its inception, the SPD was a driving force behind the petition. In 1898, August Bebel, one of the main leaders of the SPD, addressed the Reichstag (the German Assembly) as an elected representative to encourage his colleagues to sign the petition. This sparked a commotion in which Bebel was booed by the rest of the members except for the SPD representatives who supported him. Bebel then ridiculed the law, stating that if the police were actually to imprison all homosexuals in the city of Berlin alone, they would need to “build at least two new prisons” to accommodate them, because homosexuality “concerns thousands of people from all walks of life.” Bebel debated the conventions of bourgeois morality of the time, which painted homosexuality as a rare, mysterious phenomenon that only affected a few “deviant” individuals.

The last aspect of the committee’s activities was scientific research. In 1903, before Kinsey’s research, which would later become the reference for the taxonomy of sexual behaviors, Hirschfeld undertook the first statistical research on homosexuality. The study was based on a questionnaire sent to 3,000 students at the University of Charlottenburg and 5,721 metalworkers (though its methodology and content would now be considered questionable). After the study was published, a Protestant pastor and six students filed a complaint against Hirschfeld. He was fined for encouraging “perverse tendencies” in young men, even though, as his lawyer pointed out, none of the over 5,000 metalworkers interviewed felt aggrieved.

In 1905, the committee stated in one of its publications that it had accomplished one of its essential tasks: making the issue of homosexuality visible.

One thing has been achieved, and it is not the least important. The period in which the issue was kept silent and disregarded is definitively over. We are now in a period of discussion. The homosexual question has become a real issue — one that has given rise to lively debate, and one that will continue to be discussed until it is satisfactorily resolved.

The issue was widely picked up by the bourgeois press and discussed in the country’s main newspapers. In 1908 the committee estimated that over 5,000 gay men had participated in one way or another in its activities. In the Reichstag, the SPD did not waver in its fight against paragraph 175 and participated in the committee’s efforts. Drawing on their writings, August Thiele, an SPD representative, once again denounced paragraph 175 as an example of “priestly cruelty and intolerance,” which is “reminiscent of the Middle Ages, when witches were burned, heretics were tortured, and dissidents were tried with the wheel and gallows.”

In 1907, the year of the Reichstag elections, the committee sent a first-ever questionnaire to candidates asking them to take a stand on homosexual rights. It received 20 responses. In the next election of 1912, it received 97 responses, only six of which refused to support the committee’s demands. Out of these 97, 37 were elected, and 24 out of those 37 belonged to the SPD, which remained the main political force supporting homosexual rights.

The Fall of the SPD and the Decline of the Homosexual Movement

World War I marked the first blow to the committee. Just as the SPD lined up behind the German bourgeoisie and chose to support a reactionary war, leading to a rupture with a significant portion of socialists who had been active within its ranks, the committee was not immune to the rising patriotism of the time. Its publications mixed idealistic calls for peace with patriotic writings in support of the “German cause” and the “deep affection for our brothers at the front.” Hundreds of committee activists, along with thousands of its supporters, went off to war, some of them dying on the front lines.

In 1915, the committee wrote in one of its journals: “We must be, and we are, of course, prepared for any eventuality. What is necessary, however, is for the committee to be able to resist and be present when — after what we hope will be a swift and victorious end to the war — national reform efforts are revived, and consequently, the struggle for the liberation of homosexuals resumes.” A pious hope that, despite a resurgence in the committee’s activities during the 1920s, would not be realized. The rise of Nazism would roll back the progress made at the beginning of the century, and the activity of the powerless committee would decline until Hirschfeld went into exile to escape Nazi persecution. Paragraph 175 would ultimately be abolished much later, after a new wave of the LGBTQ+ movement: in 1968 in East Germany and in 1994 in the West.

For the SPD, World War I meant a definitive break with revolutionary ideas. The notion of gradual change in society brought about by the institutions of bourgeois democracy, however, was already present in an embryonic form in how the SPD, under Bernstein’s leadership, envisioned the struggle for sexual liberation. Despite taking correct positions in the Reichstag and conducting unprecedented analysis of sexuality for the time, these ideas never reached the consciousness of the SPD’s predominantly working-class base. This opened the door, decades later, to serious homophobic tendencies within the SPD itself, which attempted, in their publications (like other left-wing forces), to weaponize the homosexuality of certain high-ranking officials in the battle against Nazism.

After the betrayal of the SPD at the start of the war, the torch of the revolutionary struggle for sexual liberation was taken up by the Bolsheviks. In 1917, two months after the revolution, Russia became the first country in the world to decriminalize homosexuality.

First published in French on June 24 in Révolution Permanente.

Translation by Emma Lee

World War I marked the first blow to the committee. Just as the SPD lined up behind the German bourgeoisie and chose to support a reactionary war, leading to a rupture with a significant portion of socialists who had been active within its ranks, the committee was not immune to the rising patriotism of the time. Its publications mixed idealistic calls for peace with patriotic writings in support of the “German cause” and the “deep affection for our brothers at the front.” Hundreds of committee activists, along with thousands of its supporters, went off to war, some of them dying on the front lines.

In 1915, the committee wrote in one of its journals: “We must be, and we are, of course, prepared for any eventuality. What is necessary, however, is for the committee to be able to resist and be present when — after what we hope will be a swift and victorious end to the war — national reform efforts are revived, and consequently, the struggle for the liberation of homosexuals resumes.” A pious hope that, despite a resurgence in the committee’s activities during the 1920s, would not be realized. The rise of Nazism would roll back the progress made at the beginning of the century, and the activity of the powerless committee would decline until Hirschfeld went into exile to escape Nazi persecution. Paragraph 175 would ultimately be abolished much later, after a new wave of the LGBTQ+ movement: in 1968 in East Germany and in 1994 in the West.

For the SPD, World War I meant a definitive break with revolutionary ideas. The notion of gradual change in society brought about by the institutions of bourgeois democracy, however, was already present in an embryonic form in how the SPD, under Bernstein’s leadership, envisioned the struggle for sexual liberation. Despite taking correct positions in the Reichstag and conducting unprecedented analysis of sexuality for the time, these ideas never reached the consciousness of the SPD’s predominantly working-class base. This opened the door, decades later, to serious homophobic tendencies within the SPD itself, which attempted, in their publications (like other left-wing forces), to weaponize the homosexuality of certain high-ranking officials in the battle against Nazism.

After the betrayal of the SPD at the start of the war, the torch of the revolutionary struggle for sexual liberation was taken up by the Bolsheviks. In 1917, two months after the revolution, Russia became the first country in the world to decriminalize homosexuality.

First published in French on June 24 in Révolution Permanente.

Translation by Emma Lee

The Institute for Sexual Science: Berlin’s Forgotten Centre for Trans Activism

In the 1920s, a fancy Berlin villa was home to a gay Jewish doctor who facilitated the very first gender-affirming surgeries. In the same building, communist leaders held secret meetings with anti-colonial guerrilla fighters. The Institute for Sexual Science was like something out of a Fox News fever dream.

Nathaniel Flakin

In the 1920s, a fancy Berlin villa was home to a gay Jewish doctor who facilitated the very first gender-affirming surgeries. In the same building, communist leaders held secret meetings with anti-colonial guerrilla fighters. The Institute for Sexual Science was like something out of a Fox News fever dream.

Nathaniel Flakin

June 29, 2023

Originally published in Exberliner.

Today only a small plaque along the Spree commemorates the villa where Magnus Hirschfeld carried out the first ever gender-affirming surgeries, and where secret anti-colonial communist meetings were held in.

In the 1920s, a villa in Tiergarten sat on the banks of the Spree, near where HKW now stands. It was home to Magnus Hirschfeld, the gay Jewish doctor who facilitated the world’s first gender-affirming surgeries. In the same building, communist leaders held secret meetings with anti-colonial guerrilla fighters. This was The Institute for Sexual Science, like something out of a Fox News fever dream.

On February 27, 1912, a 19-year-old was arrested in Weißensee for walking around in women’s clothing. The suspect was charged with Grober Unfug (public nuisance).

At the police station, the suspect had to be released. It turned out that Gerda von Zobeltitz, who had been assigned male at birth, was in possession of a so-called Transvestitenschein (transvestite pass), a permit from Berlin’s police chief allowing her to wear dresses. She had gotten a medical certificate from Dr Magnus Hirschfeld explaining that it was in her nature to wear dresses. In the language of the time, she was a “transvestite personality”, and even the Wilhelmine police had to admit that arrests wouldn’t change that.

The incident prompted a half-dozen Berlin papers to report about the “boy in women’s clothing,” who made news again when she married a woman at the civil registry office.

Way back in the 1890s, Hirschfeld had made a career out of treating people who didn’t fit into the rigid gender and sexual norms of imperial Germany. Hirschfeld’s Scientific Humanitarian Committee (WhK), the world’s first gay-rights group, launched a petition to abolish Germany’s law against male homosexuality, the infamous Paragraph 175.

The Institute

In 1919, with the new Weimar Republic loosening the screws on queer people ever so slightly, Hirschfeld bought a villa in Tiergarten. The large house – or a small palace, really – on the corner of In den Zelten and Beethovenstraße had been built for the Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim. Now, it became home to the Institute for Sexual Science. There was space for consultation rooms, an enormous archive (including plenty of pornography) and an apartment for Hirschfeld and his partner. Anyone could get professional help for their sexual problems – those too poor to afford the fees could help out in the office instead. Two years later, Hirschfeld bought the building next door to add to the annex.

Hirschfeld treated patients from all walks of life and even went to colonial exhibitions to interview people from distant cultures about their sexuality. Based on his research, Hirschfeld saw that gender and sexuality manifest themselves on different levels: sex organs, other physical characteristics, sexual desire and other psychological characteristics. On these four scales, each person can be situated somewhere between male and female. Instead of two categories, men and women, Hirschfeld emphasised the importance of seeing each person’s unique gender and sexual identity.

When power was handed over to the Nazis in 1933, Hirschfeld – a gay, Jewish, socialist doctor who questioned social hierarchies – was their prototypical enemy. On May 6, 1933, Nazi stormtroopers trashed the institute; a number of Hirschfeld’s books went up in flames in the state-sponsored pyres four days later. At that time, he was outside of Germany for a speaking tour and never returned – he died in exile in 1935.

The Commies

But the Nazis had another reason to hate the Institute for Sexual Science. The villa was also a nest of secret communist activity – a hangout for Pinks but also for Reds.

Hirschfeld himself was a Social Democrat, but in the words of Babette Gross, he “had a heart for communists”. Gross had moved into Hirschfeld’s building in 1926 together with her partner, Willi Münzenberg. He was the Communist Party’s larger-than-life propaganda chief, known as the “Red Millionaire” for running one of the biggest media empires in Weimar Germany. In reality, Münzenberg never had any money himself. Only at age 37 did he settle down in a furnished room in the Tiergarten villa

The Legacy

Just a few years after the Nazis had destroyed the Institute, bombs demolished the villa as well. It took a while before Hirschfeld reentered the German public consciousness. Today, a brown metal box marks the spot next to the Spree river. Except: the location isn’t quite right. The villa would have been on the other side of Haus der Kulturen der Welt. When the plaque was installed in 1994, the new Federal Chancellery was being planned, and they didn’t want the small monument getting stuck in the middle of a construction site.

Nathaniel Flakin

Nathaniel is a freelance journalist and historian from Berlin. He is on the editorial board of Left Voice and our German sister site Klasse Gegen Klasse. Nathaniel, also known by the nickname Wladek, has written a biography of Martin Monath, a Trotskyist resistance fighter in France during World War II, which has appeared in German, in English, and in French. He is on the autism spectrum.

Originally published in Exberliner.

Today only a small plaque along the Spree commemorates the villa where Magnus Hirschfeld carried out the first ever gender-affirming surgeries, and where secret anti-colonial communist meetings were held in.

In the 1920s, a villa in Tiergarten sat on the banks of the Spree, near where HKW now stands. It was home to Magnus Hirschfeld, the gay Jewish doctor who facilitated the world’s first gender-affirming surgeries. In the same building, communist leaders held secret meetings with anti-colonial guerrilla fighters. This was The Institute for Sexual Science, like something out of a Fox News fever dream.

On February 27, 1912, a 19-year-old was arrested in Weißensee for walking around in women’s clothing. The suspect was charged with Grober Unfug (public nuisance).

At the police station, the suspect had to be released. It turned out that Gerda von Zobeltitz, who had been assigned male at birth, was in possession of a so-called Transvestitenschein (transvestite pass), a permit from Berlin’s police chief allowing her to wear dresses. She had gotten a medical certificate from Dr Magnus Hirschfeld explaining that it was in her nature to wear dresses. In the language of the time, she was a “transvestite personality”, and even the Wilhelmine police had to admit that arrests wouldn’t change that.

The incident prompted a half-dozen Berlin papers to report about the “boy in women’s clothing,” who made news again when she married a woman at the civil registry office.

Way back in the 1890s, Hirschfeld had made a career out of treating people who didn’t fit into the rigid gender and sexual norms of imperial Germany. Hirschfeld’s Scientific Humanitarian Committee (WhK), the world’s first gay-rights group, launched a petition to abolish Germany’s law against male homosexuality, the infamous Paragraph 175.

The Institute

In 1919, with the new Weimar Republic loosening the screws on queer people ever so slightly, Hirschfeld bought a villa in Tiergarten. The large house – or a small palace, really – on the corner of In den Zelten and Beethovenstraße had been built for the Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim. Now, it became home to the Institute for Sexual Science. There was space for consultation rooms, an enormous archive (including plenty of pornography) and an apartment for Hirschfeld and his partner. Anyone could get professional help for their sexual problems – those too poor to afford the fees could help out in the office instead. Two years later, Hirschfeld bought the building next door to add to the annex.

Hirschfeld treated patients from all walks of life and even went to colonial exhibitions to interview people from distant cultures about their sexuality. Based on his research, Hirschfeld saw that gender and sexuality manifest themselves on different levels: sex organs, other physical characteristics, sexual desire and other psychological characteristics. On these four scales, each person can be situated somewhere between male and female. Instead of two categories, men and women, Hirschfeld emphasised the importance of seeing each person’s unique gender and sexual identity.

When power was handed over to the Nazis in 1933, Hirschfeld – a gay, Jewish, socialist doctor who questioned social hierarchies – was their prototypical enemy. On May 6, 1933, Nazi stormtroopers trashed the institute; a number of Hirschfeld’s books went up in flames in the state-sponsored pyres four days later. At that time, he was outside of Germany for a speaking tour and never returned – he died in exile in 1935.

The Commies

But the Nazis had another reason to hate the Institute for Sexual Science. The villa was also a nest of secret communist activity – a hangout for Pinks but also for Reds.

Hirschfeld himself was a Social Democrat, but in the words of Babette Gross, he “had a heart for communists”. Gross had moved into Hirschfeld’s building in 1926 together with her partner, Willi Münzenberg. He was the Communist Party’s larger-than-life propaganda chief, known as the “Red Millionaire” for running one of the biggest media empires in Weimar Germany. In reality, Münzenberg never had any money himself. Only at age 37 did he settle down in a furnished room in the Tiergarten villa

.

“The many corridors were plastered with the sexual symbols of primitive peoples and other relevant photographic material,” Gross recalled. “And visitors to the institute wandered through our corridors as well.” Officials of the Communist International came to appreciate the building, not just for its exotic collections, but also because it was ideal for conspiratorial meetings. With people going in and out of the institute constantly, it was impossible for police spies to keep track, so anyone could slip through a connecting door for a meeting with Münzenberg.

Gross and Münzenberg had a WG with another leading Communist, the boyish and bookish Politbüro member Heinz Neumann, famous for his slogan “Beat the fascists wherever you meet them!” The Indian Communist M.N. Roy, busy planning armed insurrection against the British Empire, lived in those rooms as well, but Hirschfeld didn’t only rent to Reds. The British author Christopher Isherwood also lived at the Institute, which is likely how he came to immortalise Münzenberg with the only lightly fictionalised character Ludwig Beyer in his novel, Mr. Norris Changes Trains.

Hirschfeld never joined the Communists. He was, at the end of the day, a wealthy doctor with no interest in the nationalization of the healthcare system. But at least one researcher at the institute was a commie: Richard Linsert, besides publishing about male prostitution, took on leading roles in the Communist Party’s paramilitary wing, the Red Front Fighters League, as well its spy service, the Antimilitarist Apparatus. While the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) campaigned for the abolition of Paragraph 175 (which only happened in 1994), there were limits to its progressive views: Linsert never made it onto the Central Committee, due to concerns that a gay man would be subject to blackmail.

“The many corridors were plastered with the sexual symbols of primitive peoples and other relevant photographic material,” Gross recalled. “And visitors to the institute wandered through our corridors as well.” Officials of the Communist International came to appreciate the building, not just for its exotic collections, but also because it was ideal for conspiratorial meetings. With people going in and out of the institute constantly, it was impossible for police spies to keep track, so anyone could slip through a connecting door for a meeting with Münzenberg.

Gross and Münzenberg had a WG with another leading Communist, the boyish and bookish Politbüro member Heinz Neumann, famous for his slogan “Beat the fascists wherever you meet them!” The Indian Communist M.N. Roy, busy planning armed insurrection against the British Empire, lived in those rooms as well, but Hirschfeld didn’t only rent to Reds. The British author Christopher Isherwood also lived at the Institute, which is likely how he came to immortalise Münzenberg with the only lightly fictionalised character Ludwig Beyer in his novel, Mr. Norris Changes Trains.

Hirschfeld never joined the Communists. He was, at the end of the day, a wealthy doctor with no interest in the nationalization of the healthcare system. But at least one researcher at the institute was a commie: Richard Linsert, besides publishing about male prostitution, took on leading roles in the Communist Party’s paramilitary wing, the Red Front Fighters League, as well its spy service, the Antimilitarist Apparatus. While the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) campaigned for the abolition of Paragraph 175 (which only happened in 1994), there were limits to its progressive views: Linsert never made it onto the Central Committee, due to concerns that a gay man would be subject to blackmail.

The Legacy

Just a few years after the Nazis had destroyed the Institute, bombs demolished the villa as well. It took a while before Hirschfeld reentered the German public consciousness. Today, a brown metal box marks the spot next to the Spree river. Except: the location isn’t quite right. The villa would have been on the other side of Haus der Kulturen der Welt. When the plaque was installed in 1994, the new Federal Chancellery was being planned, and they didn’t want the small monument getting stuck in the middle of a construction site.

Organised by the Nazi party, students of the Academy for Physical Exercise (Hochschule für Leibesübungen) march in front of the building of the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin immediately prior to pillaging it on May 6, 1933.

The memory is kept alive by the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, which became active in 1983, when West Berlin was commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Nazis seizing power. As the society’s co-founder Ralf Dose recalls, “the official commemoration didn’t include many different victims of fascism: the Communists of course, the Sinti and Roma, especially not the so-called Asocials, but also the gays and lesbians.” So activists from Berlin’s gay liberation movement organised their own lecture series. Over the last 40 years, the society has expanded its focus beyond homosexuality, since Hirschfeld’s institute also offered counselling for straight people, including contraception and abortion. Dose has since written a biography: Magnus Hirschfeld – The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. Currently, they are looking to build a queer archive in the old Kindl Brewery, next to SchwuZ.

Remembering this long history is important when confronting homo- and transphobia today. When people spread conspiracy theories about trans people being part of a nefarious plot by “cultural Marxists” to destroy civilization, it’s kind of ridiculous. But there might be a kernel of truth: both queers and communists seek to overturn patriarchal capitalist hierarchies and create a society where everyone is free and equal. The villa in Tiergarten is a reminder of how intertwined these two liberation movements were and still are. Communists of the 1920s were not just the avant garde in politics, but also painting, music and sexuality. It was the Stalinist counterrevolution that cut off all that emancipatory potential.

The memory is kept alive by the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, which became active in 1983, when West Berlin was commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Nazis seizing power. As the society’s co-founder Ralf Dose recalls, “the official commemoration didn’t include many different victims of fascism: the Communists of course, the Sinti and Roma, especially not the so-called Asocials, but also the gays and lesbians.” So activists from Berlin’s gay liberation movement organised their own lecture series. Over the last 40 years, the society has expanded its focus beyond homosexuality, since Hirschfeld’s institute also offered counselling for straight people, including contraception and abortion. Dose has since written a biography: Magnus Hirschfeld – The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. Currently, they are looking to build a queer archive in the old Kindl Brewery, next to SchwuZ.

Remembering this long history is important when confronting homo- and transphobia today. When people spread conspiracy theories about trans people being part of a nefarious plot by “cultural Marxists” to destroy civilization, it’s kind of ridiculous. But there might be a kernel of truth: both queers and communists seek to overturn patriarchal capitalist hierarchies and create a society where everyone is free and equal. The villa in Tiergarten is a reminder of how intertwined these two liberation movements were and still are. Communists of the 1920s were not just the avant garde in politics, but also painting, music and sexuality. It was the Stalinist counterrevolution that cut off all that emancipatory potential.

Nathaniel Flakin

Nathaniel is a freelance journalist and historian from Berlin. He is on the editorial board of Left Voice and our German sister site Klasse Gegen Klasse. Nathaniel, also known by the nickname Wladek, has written a biography of Martin Monath, a Trotskyist resistance fighter in France during World War II, which has appeared in German, in English, and in French. He is on the autism spectrum.

No comments:

Post a Comment