The Jewish false messiah who died a Muslim: The Shabbtai Zvi enigma

He began as an eccentric with unusual customs, sparked a revolution and drew masses of believers in the Jewish world; Even after his conversion to Islam and the subsiding euphoria around him, the Sabbatean movement influenced Hasidism, and some argue, Zionism as well

Shmuel Munitz|14:51

He only lived for 50 years, but in that tumultuous time, he became the greatest false messiah the Jewish world has known. Shabbtai Zvi, who caused euphoria throughout the Diaspora, has fascinated generations of scholars.

Shabbtai Zvi was born in 1626 in Izmir in the Ottoman Empire. The date we have for his birth is the 9th of Av, which fits nicely with the belief that the Messiah will be born on the day Jews remember the destruction of the two temples.

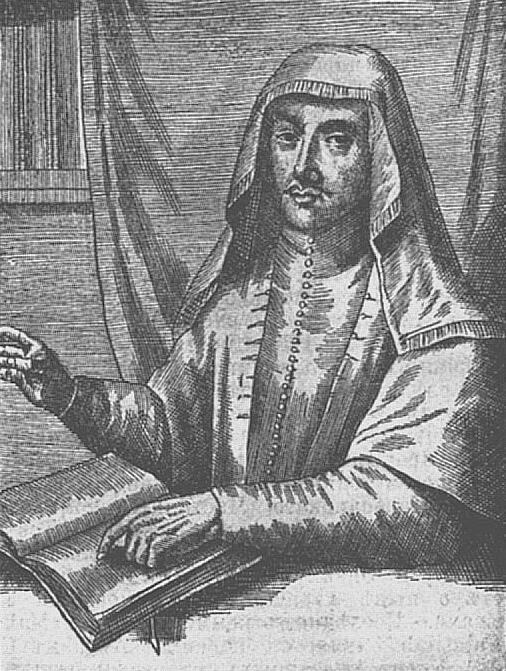

Shabbtai Zvi

(Illustration: from the book of Thomas Conan, Amsterdam, 1669)

As a young man, he studied Kabbalah, which greatly influenced the Sabbatean movement. Renowned scholar, Gershom Scholem, claims there is evidence to suggest that he suffered from bipolar disorder. His moments of transcendence and enlightenment followed by great sadness are well documented. At a certain point, Zvi declared himself to be the Messiah. He would publicly cry out God’s full four-lettered name, despite clear Halachic prohibition on doing so. At first, he wasn’t taken seriously.

He was forced to divorce his first two wives as he wouldn’t sleep with them and refused to touch them. His strange behavior, coupled with activities in contravention of Halacha and his messianic claims, led to his expulsion from Izmir. He found his way to Salonica where he “married” a Sefer Torah in a festive celebration including a chuppa. Yes, he really did. He was eventually thrown out of Salonica too.

In 1658, he arrived in Kushta (Istanbul), where he continued with his rather unusual customs including celebrating the three Pilgrimage Festivals of Pesach, Shavuot and Sukkot in the same week. These practices, compounded by his announcement of the cancellation of mitzvot, led to the community of Kushta expelling him too. With his tail between his legs, he returned to Izmir and made it to Eretz Israel in 1662 by way of Rhodes and Cairo.

He married a woman named Sarah, a prostitute from Livorno, whom he arranged to have brought to Eretz Israel. In 1665, searching for a cure for his troubled soul, he traveled to Gaza to meet scholar and mystic, Nathan of Gaza. Instead of curing him, Nathan of Gaza convinced Shabbtai that he was indeed the Messiah. Every messiah needs one esteemed individual to believe in him.

Nathan, who claimed to have had a vision of Shabbtai as the Messiah before their meeting, took on the role of prophet regarding the Messianic issue: He sent letters declaring the good news all over the Jewish world. Masses, including prominent rabbis, were very excited about the news. Some communities even introduced a prayer for the wellbeing of Shabbtai Zvi, “Messiah of Israel”, referring to him as AMIRAH, a Hebrew acronym for the phrase "Our Lord and King, his Majesty be exalted" (Adoneinu Malkeinu Yarum Hodo). As the Sabbatean movement initially led to mass return to mitzvot, the opposition of rabbinical institutions was minimal. Until it inflated and got out of control.

Nathan of Gaza

(Illustration: from the book of Thomas Conan, Amsterdam, 1669)

“A broad variety of weird and wonderful explanations have been given to account for the movement’s enormous, rapid success,” says Dr. Avishai Bar-Asher, head of the Jewish Studies program at the Jewish Thought Department at the Hebrew University. “At its peak, Sabbatean Messianism was a mass movement. It was by no means marginal. It wasn’t a small defined group like the Messianic faction of Chabad for example - whose adherents believe that the Lubavitcher Rebbe is the Messiah. This was a movement that was almost everywhere.“

How many Jews followed him at the time? “A lot. Almost no Diaspora community was untouched by Sabbateanism. Multitudes followed him – in Turkey, Greece, Amsterdam, Poland, Hamburg, Morrocco, Italy and as far afield as Yemen. There were always people who opposed the movement. But the appeal was enormous. The movement spread quickly into diverse regions. At the movement’s peak, even initial opponents became adherents. People sold their property and started preparing for the journey to the Eretz Israel and for Redemption.“

Abrogation of prohibitions was a core revolutionary idea in the movement: Sabbateanism held that the historical role played by commandments that had accompanied the Jewish People had come to an end in the Messianic Age. Stretching Kabbalistic beliefs, Sabbateanism claimed that to repair the world, one must perform “transgressions for their own sake.” Sin for the sake of sin. Sabbatean theology, developed by Nathan of Gaza, stated that the sins were Shabbtai Zvi’s way of getting close to transgressors, to stop them and bring about correction.

“Shabbtai Zvi was first and foremost a Kabbalist. He operated within the Kabbalistic tradition. This was his theology and practice. He enhanced and improved it,“ explains Dr. Bar-Asher. “The divine and cosmic connection between male and female is well known in Kabbalah, as is the idea that any human sexual act affects the divine system.”

Even at the height of Sabbatean euphoria, there were pockets of resistance including Rabbi Jacob ben Aaron Sasportas from Hamburg. “Sasportas fought a long hard battle against Shabbtai Zvi, and kept a record of it for posterity," sats Dr. Bar-Asher. "It’s important to understand that even Sasportas would praise the positive aspects he identified in Sabbatean activity – like the mass movement of returning to religious practice. People became more religious and the synagogues filled up. This was regarded in a positive light, even by those opposing Shabbtai Zvi’s messianic claims.“

The Temple Mount

(Photo: AP)

Samuel Primo was Shabbtai Zvi’s personal scribe. Bar-Asher tells us that “Primo was the ‘Messiah’s scribe.' He wrote down what Shabbtai Zvi said and spread his message far and wide. He was among the people closest to Shabbtai Zvi – what we would call today a personal secretary and public relations officer. He remained loyal to Shabbtai Zvi even after the latter’s conversion to Islam and - despite claims that he completely left the movement - acted as an underground Sabbatean leader in Adrianople, Turkey for many years.“

His third wife, Sarah, was a prostitute – something Sabbateans never denied. This is reminiscent of the biblical story of Hosea who was commanded by God to marry a prostitute and have children with her. The idea is that the messiah, by his actions, will begin turning around the current order,” Bar-Asher explains. “Before the Messiah arrived, the world had operated under a certain order. Messianic Sabbateanism believed that the Messiah would change that order and all kinds of things that had been forbidden, would now be allowed,” he explains.

Bar-Asher advises caution regarding details surrounding Shabbtai Zvi’s wives and his refusal to sleep with his first two wives. Various groups, both supporters and opponents, had a plethora of vested interests in how they portrayed Zvi.

“Shabbtai Zvi’s sexual behavior was a critical link in stories told about him. We must remember that in addition to many followers during Shabbtai Zvi’s lifetime, there were all sorts of groups and individuals that continued Shabbtai Zvi long after his death. Some of these groups found it prudent to portray him in a certain way, while others chose to paint a more ascetic, conservative picture. Shabbtai Zvi’s biography is adorned with efforts to portray a perfect character, so it’s hard to tell where the writer’s imagination ends and historical reality begins. Opponents of Sabbateanism also clearly had a vested interest in portraying him in a certain manner.“

The spectacular downfall

In 1666, a man named Nehemiah HaCohen informed on Shabbtai Zvi to the Ottoman authorities who feared rebellion. Zvi was subsequently declared a traitor. He was imprisoned and the Sultan gave him two options: execution or conversion to Islam. He chose Islam and was granted the new name of Aziz Mehmed Effendi.

Most of Shabbtai Zvi’s followers were shocked and abandoned their beliefs following the conversion. A minority did follow him converting to Islam in his wake. Small groups within Jewish communities continued with their, now clandestine, Sabbatean beliefs.

“Nathan of Gaza – who originally opposed Shabbtai Zvi’s conversion to Islam – ultimately didn’t abandon him, going to great lengths to update his messianic view after Zvi’s conversion. Nathan, along with others held fast to Shabbtai Zvi and tried to come up with all sorts of hidden reasons for his conversion to Islam, viewing the conversion as part of his messianic process,” Bar-Asher tells us.

“After Shabbtai Zvi’s death in 1676, there was a need to update the messianic theology from a different angle. His remaining followers developed a variety of intriguing systems. Some believed he had just “vanished” and would return to reveal himself at some later date. Others believed that Shabbtai Zvi was only the first messiah, Mashiach ben Yosef, announcing the arrival Mashiach ben David - the final messiah who would bring about full redemption.

Bar-Asher adds that “From his third wife, Sarah, Shabbtai Zvi had a son, Ishmael Zvi. Some followers pinned their hopes on him. It’s unclear what became of him.”

Sabbateanism resonates for years after his death: In the 18th century, another false messiah, Yaakov Frank arose. The Frankist movement had many similarities with Sabbateanism: Believers abrogated religious laws as part of the cult surrounding their messiah, and a Sabbatean sect called the Dönme, descended from followers of Shabbtai Zvi who converted to Islam, exists in Turkey to this very day.

No comments:

Post a Comment