North Korea is testing more missiles, Iran is rushing for a bomb, India and Pakistan are renewing the arms race — things are getting as scary as the Cold War.

N KOREA DO NOT HAVE NUKES

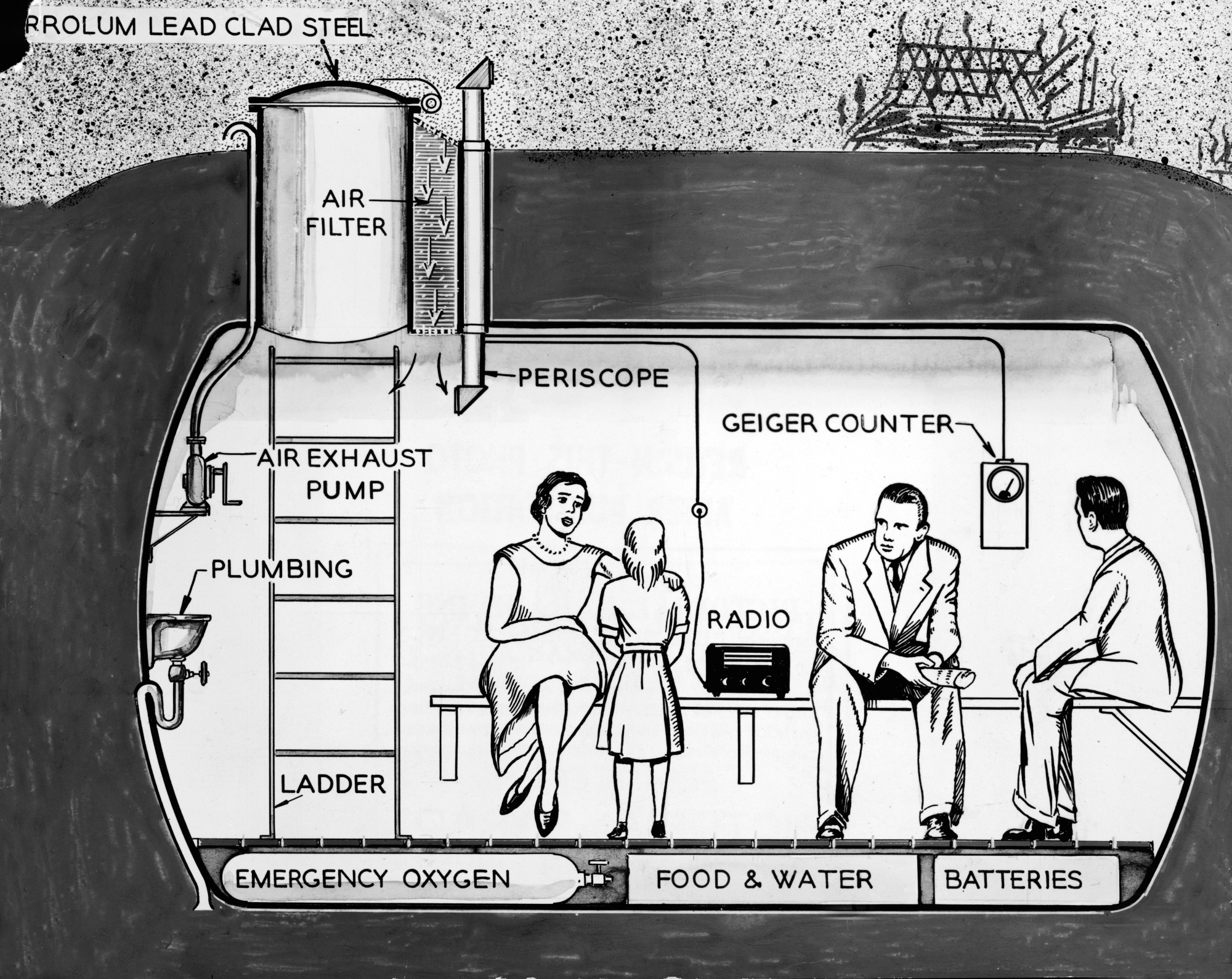

Falling out.Source: Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

By Max Hastings

August 5, 2023

Suddenly, on this 78th anniversary of the dropping of “Little Boy” on Hiroshima by Colonel Paul Tibbets’ Enola Gay, we are again being forced to think about The Bomb. Millions of people are flocking to see Christopher Nolan’s new biopic Oppenheimer, which concludes with its protagonist’s gloomy assertion to Albert Einstein that, through the creation of atomic weapons, mankind signed its own death warrant.

Meanwhile, North Korea last month tested a new ballistic missile. Iran seems set on a course that is almost certain to end in its possession of nuclear arms. Russian President Vladimir Putin routinely rattles his nuclear saber, most recently over redeploying some of his nation’s many missiles to neighboring ally Belarus.

Less noticed by the world, in Asia three nuclear powers — China, India and Pakistan — are committing serious resources to strengthening their capabilities. Ashley Tellis’s authoritative 2022 book Striking Asymmetries explains that until recently, the Asian nations were content with a posture of minimal deterrence — holding limited stocks of weapons underground.

These suffice to ensure a devastating second-strike capability against an aggressor, without requiring a huge investment in early-warning systems for rapid response, such as Russia and America possess. The Asian states’ nuclear arsenals have in the past served political purposes more than military ones.

Today, however, that is changing. China is dramatically enlarging its missile and warhead inventory. Pakistan, albeit on a much lesser scale, is doing likewise, chiefly because in a war with the hated Indians its conventional forces could not hope to prevail. India feels unable to remain passive when its two potential adversaries escalate.

Given the unyielding tensions in the region, especially between India and Pakistan, the danger of nuclear conflict is arguably greater in Asia than in the West.

Most of us live out our lives baffled by the enormity of the nuclear menace. We take refuge in not thinking too much about it. We also tell ourselves that no rational national leader would unleash such weapons, at the risk of precipitating mankind’s total destruction.

Robert Oppenheimer thought something of this sort, before Hiroshima. When the brilliant physicist Leo Szilard lobbied him unsuccessfully to oppose the use of his terrible creation and recorded the strange, enigmatic remarks made by the director of the Los Alamos laboratory. “Oppie” told Szilard: “The atomic bomb is shit.”

“What do you mean by that?” questioned Szilard.

Oppenheimer replied: “Well this is a weapon which has no military significance. It will make a big bang — a very big bang — but it is not a weapon which is useful in war.”

When Oppenheimer said that, he was almost certainly mindful of the looming prospect of his terrible progeny being unleashed on Japan, which was incapable of any response. He then assumed, however, that if a future enemy possessed the capability to retaliate in kind, no national leader would seek to use an atomic bomb in pursuit of battlefield advantage.

Oppenheimer wrote in 1948:

[T]he weapons tested in New Mexico and used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki served to demonstrate that with the release of atomic energy quite revolutionary changes had occurred in the techniques of warfare. It was clear that with nations committed to atomic armament, weapons even more terrifying, and perhaps vastly more terrifying, than those already delivered would be developed; and … that nations so committed to atomic armament could accumulate these weapons in truly terrifying numbers … The atomic bomb must show that war itself is obsolete.

In one of his most memorable phrases, the scientist likened the US and Soviet Union to “two scorpions trapped in a bottle”: If they come to blows, both must perish. Today, almost eight decades on, Oppenheimer’s judgement about that looks rational, but oversanguine. Whatever the existential awareness of prudent national leaders, the peril persists that an aberrational figure — an Iranian ayatollah, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, an impassioned Pakistani, even a Donald Trump — might not accept Oppenheimer’s verdict, reprised by many authoritative voices since, that there can be no possible “winner” from a nuclear exchange.

I am nagged by consciousness that two years ago, I was among many students of strategy and international affairs who never contemplated the prospect of Putin launching a war to conquer Ukraine, because the cost to his own country must be so appalling. Yet he did so. His logic proved to be different from our logic. How much different, and whether also extending to nuclear weapons, remains uncertain.

In Oppenheimer, General Leslie Groves asks the scientist what are the chances that a nuclear explosion will destroy the world. Almost zero, says Oppenheimer, to which the general responds laconically: “I would have preferred zero.” Mankind will never again enjoy the luxury of zero.

Nolan’s movie captures the equivocations, the ambiguities, that overhung Oppenheimer’s career after August 1945, as he wrestled with the stupendous dilemmas and forces unleashed by his achievement at Los Alamos. His McCarthyite accusers at the hearings of 1954, seeing these as evidence of disloyalty to his country, pounced on his prewar political equivocations, notably including support for Spain’s republicans and communists in their 1936-39 civil war.

Yet the American right ignored the fact that most decent people in the democracies deplored the triumph of General Francisco Franco’s fascists — and the fact that American businesses had made millions out of backing them. Before World War II, Oppenheimer was politically no further to the left than were many educated Americans, disgusted by the social failures within their own country and the brutality of 1930s capitalism.

For better or worse, from 1941-45 the Soviet Union had been the foremost ally of the US against Germany. In the eyes of most biographers and historians, Oppenheimer was always an American patriot. He was simply a scientific genius who tried also to think beyond national frontiers.

He opposed the creation of the H-Bomb, because it posed an even more devastating threat to the planet that did the A-Bomb. Yet he became an advocate of developing lower-yield tactical weapons, in hopes — which most strategists have since deemed vain — that it might be possible to limit the scope of a nuclear exchange.

He pursued the dream of international control of atomic arms, writing, again in 1948: “We would desire … a situation in which our pacific intent was recognized and in which the nations of the world would gladly see us the sole possessors of atomic weapons. As a corollary, we are reluctant to see any of the knowledge on which our present mastery of atomic energy rests, revealed to potential enemies … The security of all peoples needs new systems of openness and cooperation.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Henry Stimson, who as secretary of war was among the leading sponsors of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wrote likewise shortly before his death in 1950: “The riven atom, uncontrolled, can be only a growing menace to us all … Lasting peace and freedom cannot be achieved until the world finds a way toward the necessary government of the whole.”

Such words showed that he, like Oppenheimer, had come to believe that only international cooperation on an unprecedented scale could make the planet secure. Yet if Stimson were alive today, he might feel obliged to acknowledge that a world which cannot cooperate effectively to overcome climate change is even less likely to work together to save itself from the nuclear menace.

We may cherish hopes that nuclear arms limitation, as practiced by American and Russian leaders — between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, between Barack Obama and Putin — may again return to fashion. But no power that considers itself threatened by mortal foes, as are all the current nuclear weapons holders, is ever likely to renounce a second-strike capability, or to agree to place its weapons under the control of any international body.

A significant portion of the British people, myself among them, sometimes toy with the idea of giving up our submarine-based nuclear weapons. These are hugely expensive for a nation much less prosperous than the US. Most strategy gurus have long dismissed them as ridiculous: They depend on American technology, and it is impossible to imagine a British government using them if our country was abandoned by the US.

Yet today, it has become almost unthinkable that in a world in which Putin routinely threatens Europe, Britain will renounce its deterrent. Moreover, the danger appears real that a future US president might reduce, or even withdraw, military support for the continent, including the American nuclear umbrella.

Another issue to which Oppenheimer returned again and again in public debate before his death in 1967 was that of the need for honesty by politicians about nuclear issues. He argued that many Washington warlords hide inconvenient truths behind the fig leaf excuse of national security.

He wrote in 1953:

[T]here are and always will be, as long as we live in danger of war, secrets that it is important to keep secret … some of these, and important ones, are in the field of atomic energy. But knowledge of the characteristics and probable effects of our atomic weapons, of — in rough terms — the numbers available, and of the changes that are likely to occur within the next years, this is not among the things to be kept secret. Nor is our general estimate of where the enemy stands.

If Oppenheimer had lived to hear Reagan announce his Strategic Defense Initiative to the American people in a nationwide broadcast in March 1983, he would have perceived this as a classic example of a leader, apparently deluded about nuclear realities, offering a fantasy that his countrymen yearned to embrace.

The day after the president spoke, I had a chance conversation with Britain’s chief of defense staff, General Sir Edwin Bramall. He said despairingly: “Our scientists say it’s time for the funny farm” — for Reagan, the general meant. Only a small faction of mavericks on either side of the Atlantic believed that it might be feasible to create a national missile-defense system such as Reagan proposed. And had the Americans done so, it would have inflicted a deadly blow on Cold War stability — the balance of terror. As it was, billions of dollars were wasted chasing an illusion.

When I was three days old, in December 1945, my father, a journalist like myself and who had spent the previous six years as a war correspondent, composed a letter about the circumstances of himself and Western society as he then saw it, which he gave me on my 21st birthday. He wrote: “You’ve come into the world at one of the strangest and most dangerous hours in human history. Europe … is back in the Dark Ages. The development of the atom bomb has introduced a new and haunting fear. As I write, nothing is easier than to believe that Russia and America will be at war in the Far East before you read these words.”

Robert Oppenheimer wrote in 1953: “It is possible that in the large light of history, if indeed there is to be history, the atomic bomb will appear not very different than [it did] in the bright light of the first atomic explosion. Partly because of the mood of the time, partly because of a very clear prevision of what the technical developments would be, we had the impression that this might mark, not merely the end of a great and terrible war, but the end of such wars for mankind.”

Oppenheimer was half right: Though there have been many wars in the world since 1953, none of them has been an existential contest between great powers, such as was World War II, and many of us believe this to be, in large measure, a consequence of the balance of nuclear terror. Moreover, contrary to my father’s fears, my own life and that of most of my generation has been amazingly unclouded by the monstrous new reality created by Robert Oppenheimer.

Stanley Kubrick aimed to be ironic when he subtitled his classic nuclear horror story Dr. Strangelove: “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” Few of us have got quite that far. But, on this tragic anniversary of Hiroshima, we should surely seek to offer a message of hope to our children and grandchildren, such as every generation must pass to the next: “Look at us — we made it, against the odds and Oppenheimer’s fears. So can you.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Max Hastings at mhastings32@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

Max Hastings is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former editor in chief of the Daily Telegraph and the London Evening Standard

No comments:

Post a Comment