Anna Conkling

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Getty

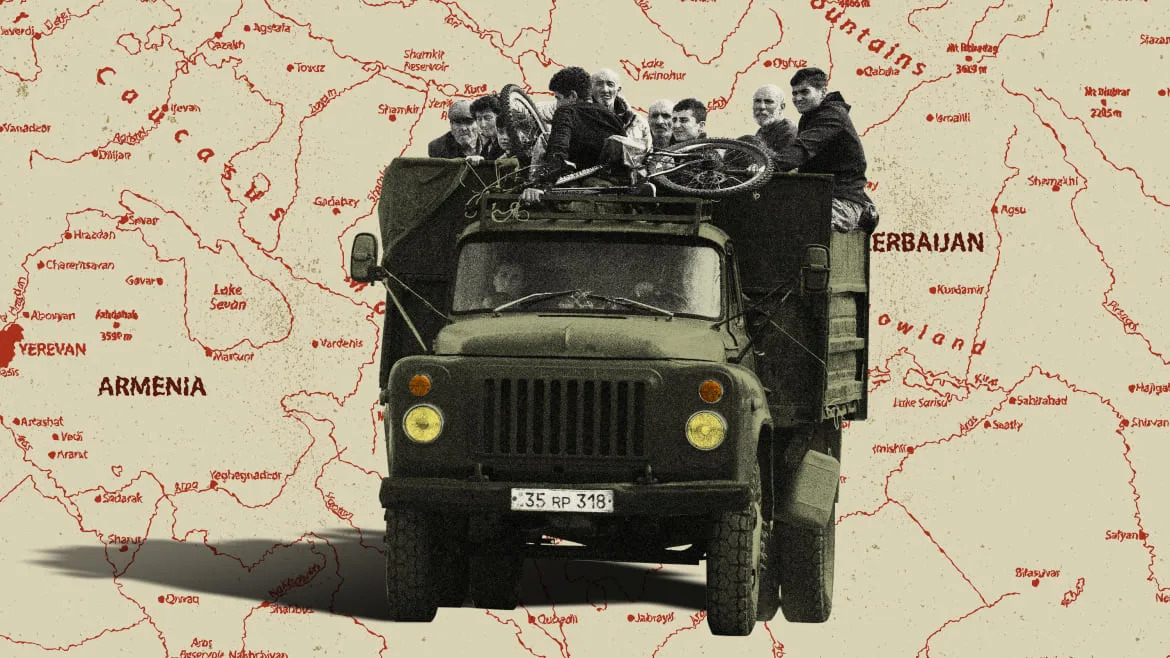

GORIS, Armenia—Two ethnic Armenian soldiers who survived the blitzkrieg onslaught against Nagorno-Karabakh told The Daily Beast they witnessed apparent war crimes committed against civilians who lived in the disputed enclave.

The assault on Nagorno-Karabakh last week was carried out by Azerbaijan despite the presence of Russian peacekeepers who had been defending the residents of the border region. It took only two days for Azerbaijan to successfully take control of the enclave after the assault began on Sept. 19. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has since accused its Russian ally of failing to intervene.

One civilian allegedly had his leg cut in two by a bullet from a sniper that struck him during the attack, according to the soldiers. They also told The Daily Beast that they had witnessed indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas, in contravention of the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statue on war crimes.

The University Network For Human Rights, a non-governmental organization documenting crimes against humanity are currently in Armenia collecting witness testimonies of war crimes allegations against Azerbaijani soldiers. Among them are forced deportation, attacks on civilian infrastructure, and forced deportation.

“People are fearful to say anything, because they still have relatives in Nagorno-Karabakh,” said Anoush Baghdassarin, a consultant attorney for The University Network For Human Rights, who has spoken to around 25 families in recent days about human rights violations during the war.

First Look Inside the Historic Mass Exodus Putin Failed to Prevent

“Every single person that we have been speaking to are a victim of forced displacement and ethnic cleansing. We have been documenting their departure, we’ve been documenting what happened since last Tuesday, Sept. 19,” Baghdassarin told The Daily Beast.

“People have been telling us that as fast as they could, they went into bunkers or they fled into forests, and they had to leave behind the people who were too sick or too elderly to leave with them. Telling us [that] many of them are still missing, they haven’t heard from them, haven’t had any contact with them, and they don’t know if they are dead, where they are,” said Baghdassarin.

“We’ve been hearing a lot of stories of flight, of fear, of missing people, and of loss. People have left their homes. 30 minutes before soldiers were coming to their village, they fled to the next village,” she added.

“When Armenians get to the border, Azerbaijan is scanning the car and going in and looking at the individuals in the car, and taking out the men. One woman told me she had read that a boy that they took out of the car’s ear was cut off at the border, but it’s not corroborated,” said Baghdassairn.

Refugees wait in their car to leave Karabakh for Armenia, at the in Lachin checkpoint, on September 26, 2023.

Emmanuel Dunand / AFP

Azerbaijan’s war on Nagorno-Karabakh was not something the breakaway region’s military expected. They were not prepared for the invasion and did not have enough bullets in their rifles to ward off the enemy force. In just a matter of hours, they would surrender to Azerbaijan’s military, leaving the fate of their homeland that residents refer to as “Artsakh” to become occupied by Baku.

In a series of interviews with The Daily Beast, the two soldiers—who agreed to speak on the condition of using their first names—recounted additional horrors they allege to have witnessed as a part of Nagorno-Karabakh’s military.

The fighting began around 1 p.m., said Amik, one of the soldiers who spoke to The Daily Beast outside of a humanitarian aid center in Goris, Armenia. He was at his military post in one of Nagorno-Karabakh’s villages that he declined to name at the time.

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh gather around a fire to warm themselves after getting stuck in a queue of vehicles on the road leading towards the Armenian border, in Nagorno-Karabakh, September 25, 2023.

David Ghahramanyan / Reuters

“We didn’t know it would start,” he said while sitting with his mother, father, and brother outside of a humanitarian aid center in Goris, Armenia. “We understood it won’t be a long war. There was no sense. We have limited people, we didn’t have weapons, we had one grenade launcher, but it didn’t shoot, there were no projectiles,” he added.

Azerbaijan quickly advanced on Nagorno-Karabakh, and Amik came face to face with the invading force. He said that first, his position was bombed by Azerbaijani soldiers. Then he saw in another area of the village that Russian peacekeepers, too, were under shelling. But shortly afterwards, Amik said, “We saw 50-60 guys started to go in our direction with weapons. We responded.”

Amik and his brigade fought for 24 hours before being forced to surrender to Azerbaijani soldiers. At that time, Amik said, “We saw killings of civilians; 13 kids died in Stepanakert. I saw how they bombed (civilians). They bombed with artillery, planes from Sushni,” a city in Nagorno-Karabakh that became occupied by Azerbaijan after the 2020 war in the region.

“I saw injuries from shells and from bombing. There was a man with no hand or leg. There were dead in my unit, three to four people in each post. We shot back. Stayed for almost the whole day. On September 20, [the war] ended at 1:30 p.m.,” Amik added.

On September 20, Amik’s brigade was told by his commanding officers that the war was over and that it was time to surrender their weapons. “We knew they would kill us, we knew we would die,” he said.

Amik managed to escape from his position through a forest that brought him to Stepanakert, where he met his family, who were already there waiting for him. “We felt like losers. We are here,” Amik said as he looked around at the humanitarian aid centers surrounding him.

The soldier believes that Azerbaijani citizens will move into homes in Nagorno-Karabakh that have been deserted in the aftermath of the war. Meanwhile, Amik and the 70,000 other refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh are left with “No home, nothing. We don’t know where to go.”

Thousands of refugees are now facing the same experience as Amik. They do not know where they should go next, and many are still grasping to understand how their lives could be destroyed in just one day.

Vehicles carrying refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh waiting to cross the Armenian border, in Nagorno-Karabakh, September 25, 2023.

David Ghahramanyan / Reuters

On the grounds of the same humanitarian aid center as Amik, a 22-year-old soldier named Robert was sitting with his grandmother, parents, and brother. He told The Daily Beast that he saw an Azerbaijani sniper “shoot the leg of a civilian,” which was sliced off by the bullet.

Robert was able to escape with his family while dressed in plain clothing. But he said he knew of other soldiers who were unable to get out of Nagorno-Karabakh.

“They [Azerbaijan] won’t let them leave. That’s what I have heard. I can’t explain this feeling. It’s very tough as my friends were fighting. The hardest is to lose friends,” said Robert

“There is no Artsakh anymore,” he added.

The Daily Beast.

Fri, September 29, 2023

By Andrew Osborn

(Reuters) - Early on September 19, Azerbaijan's president set in motion a lightning-fast military plan months in the making that would redraw the geopolitical map and avenge an ignominious defeat suffered by his father some 30 years before.

In power for two decades and with one successful war already under his belt, President Ilham Aliyev had often spoken of returning the mountainous Nagorno-Karabakh enclave to Azerbaijan's full control after its ethnic Armenian inhabitants broke from Baku's rule in the early 1990s.

Now, a confluence of factors had convinced Aliyev, 61, that the time was right, Elin Suleymanov, Azerbaijan's ambassador to Britain, told Reuters.

"History takes turns and zigzags," Suleymanov said. "We could not do this earlier and it would probably not be a good idea to do it later."

"The stars aligned for certain reasons and President Aliyev saw the alignment," said Suleymanov, who previously worked in Aliyev's office.

Prominent among these "stars" was the new inability or unwillingness of Russia, the West, or Armenia to intervene to protect Nagorno-Karabakh. The self-governed enclave had 10,000 fighters at its disposal according to Azerbaijan, whose own army - estimated at over 120,000-strong by Western experts - dwarfed it.

In conversations with Reuters, two senior officials and a source who has worked with Aliyev underscored that the decision to take back the breakaway region took shape over months as diplomatic realities shifted.

It was also deeply personal for the president, they said.

Speaking to the people of Azerbaijan the day after his troops had gone in, Aliyev said he had ordered his soldiers not to harm civilians. Baku would later say that 192 of its soldiers had been killed in the operation that followed; the Karabakh Armenians that they had lost over 200 people.

"President Aliyev is completing something that his father could not do because he ran out of time," said one of the sources, who requested anonymity because they were not authorised to give comments to the media.

Aliyev's actions have loosened Russia's decades-long grip on the strategically important South Caucasus region which is crisscrossed with oil and gas pipelines, lies between the Black and Caspian seas, and borders Iran, Turkey and Russia.

In three interviews, one before and two after the military operation, Aliyev's foreign policy adviser Hikmet Hajiyev said Baku's patience with the status quo had snapped.

Less than two weeks before Azerbaijani forces swept into Karabakh, Hajiyev told Reuters that Baku was not seeking any military objectives "at this stage" but remained vigilant. It could not accept what he called a "grey zone" with Karabakh's own armed security forces, which he likened to the mafia, on Azerbaijani territory, he said.

The Karabakh defence force has since disbanded under the terms of a new ceasefire deal, but they have rejected Azerbaijani criticism in the past, calling themselves a legitimate fighting force.

On the day of the military operation, after fighting abated, Hajiyev listed what he called "triggering elements" that prompted Baku to resort to military action, mentioning a landmine explosion that killed two Azerbaijani civilians earlier that day in part of Karabakh recaptured in a 2020 war.

"Enough is enough," Hajiyev said.

Aliyev also referred to the mine attack, and a similar incident which had killed four others. Karabakh Armenians called the assertions an "absolute lie." Reuters was unable to independently verify what had happened.

In the event, Russia, which has peacekeepers on the ground but is busy with its own war in Ukraine, stood to one side.

Hajiyev said Azerbaijan gave the Russians "minutes' notice" before the operation began.

Nikol Pashinyan, prime minister of neighbouring Armenia, which twice fought major wars over Karabakh, did not heed calls from opposition politicians to intervene and said his country needed to be "free of conflict" for the sake of its own independence.

The West - which had previously tried to mediate - merely urged Aliyev to halt his operation and was duly ignored.

Pashinyan went on to harshly criticise Russia for not doing enough to avert the crisis. On a conference call last week, the Kremlin denied its peacekeepers should have intervened.

Russia's foreign ministry added he was making "a massive mistake" and accused him of trying to destroy Armenia's centuries-old ties with Moscow.

WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

Trouble had been brewing for months.

With Russia distracted in Ukraine, Aliyev appeared to sense a window of opportunity.

In December last year, Azerbaijani citizens describing themselves as environmentalists unhappy about illegal mining began to block the Lachin corridor, the only road linking Karabakh to Armenia.

Karabakh officials at that time said the protesters were a front and included Azerbaijani officials. Baku denied the accusation.

Apparently reluctant to risk escalation, armed Russian peacekeepers did not act to remove the protesters by force.

In June, citing a shooting incident, Azerbaijan blocked the corridor, stopping transport including the passage of humanitarian aid. It only allowed medical evacuees out, a step that deepened Karabakh's food and medicine shortages.

Armed border guards manned a checkpoint close to a base for the Russian peacekeepers, who again did not intervene. Baku ignored calls from Washington and Moscow to unblock the road, citing a weapons-smuggling risk.

In May, in an attempt to advance peace negotiations, Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan made what looked like a breakthrough offer: Armenia was ready to recognise Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, if Baku guaranteed the security of its ethnic Armenian population.

Aliyev appears to have seized on what he saw a long overdue admission of reality as a sign of weakness. The source who has worked with Aliyev called the shift "very important."

"After Armenia recognised Karabakh as an integral part of Azerbaijan, what status can the criminal regime that has been calling the shots in Karabakh for 30 years have?," Aliyev told Azerbaijanis in his victory speech last week.

On the same day, the Russian foreign ministry accused Pashinyan of sowing the seeds of Karabakh's demise as an ethnic Armenian enclave by recognising it was part of Azerbaijan. That, it said, had changed "the situation" for Russia's own peacekeeping contingent.

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Karabakh slipped from Azerbaijan's grasp in the chaos that followed the Soviet Union's breakup. In a 1988-1994 war, around 30,000 people were killed and over 1 million displaced, over half of them Azerbaijanis.

Aliyev's father, then President Heydar Aliyev, was forced to agree to a ceasefire that cemented Armenia's victory.

Ilham, who had succeeded Heydar on his death in 2003, signed an oil deal with a BP-led consortium a year later that gave Azerbaijan funds to start building a modern army.

More recently, Azerbaijan benefited financially from the West's decision to cut energy purchases from Russia. The European Commission last year agreed to double imports of Azerbaijani natural gas by 2027.

For years, Moscow's alliance and defence pact with Armenia - where it has military facilities - deterred Baku from using force even as Russia sold weapons to both sides.

But Moscow's ties with Armenia began to sour in 2018 when Pashinyan, a former journalist, led street protests that brought him to power at the expense of a long line of pro-Russian Armenian leaders.

And as Azerbaijan's army overhaul and modernisation drive intensified, Armenia limped from crisis to crisis.

Seeing there was no love lost between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Pashinyan, who had spoken in favour of ties with the West, Aliyev tested the waters. In 2020, he launched a 44-day war that his army won - with the help of advanced Turkish drones, clawing back a chunk of Karabakh.

Russia brokered a ceasefire that appeared to be a win for Moscow, allowing it to deploy nearly 2,000 Russian peacekeepers to Karabakh. The step gave it a military footprint in Azerbaijan, an apparent buffer against further Azerbaijani military action.

Then Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed the equation again, drawing Moscow into a war of attrition with Kyiv.

FOG IN THE AIR

On the morning of Tuesday, Sept. 19, residents of Stepanakert, Karabakh's capital and known as Khankendi by Azerbaijan, heard loud and repeated artillery fire as fog hung in the air.

What Aliyev called an anti-terrorism operation had begun, with ground forces backed by drones and artillery sweeping in to overwhelm Karabakh's defensive lines.

At least five Russians were killed in the violence that followed, in an apparent accident which Aliyev apologised to Putin for.

Within 24 hours, Baku declared victory and the Karabakh Armenian fighters agreed to a ceasefire that obliged them to disarm.

Karabakh Armenians said they felt betrayed on all sides.

"Karabakh has been left on its own: Russian peacekeepers practically don't fulfil their obligations, the democratic West turned away from us, and Armenia also turned away," David Babayan, an adviser to the leader of the Karabakh administration, complained to Reuters a day after the rout.

Babayan has since given himself up to the Azerbaijani authorities, he announced on Telegram. The administration he advised has announced its own disbandment.

"Azerbaijan regained its sovereignty at around 1:00 p.m. yesterday," Aliyev told the nation.

Four days after the operation, some of Karabakh's 120,000 Armenians began what became a mass exodus by car towards Armenia, saying they feared persecution and ethnic cleansing despite Azerbaijani promises of safety. Ten days after Azerbaijan struck, 98,000 people had fled into Armenia, the authorities there said.

The return of Karabakh paves the way for hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis who once fled it to return, a promise Aliyev's father gave repeatedly.

"President Aliyev has delivered the testament of his father," said Suleymanov, the ambassador to Britain.

(Reporting by Andrew Osborn; Editing by Frank Jack Daniel)

No comments:

Post a Comment