Scars left by global prospectors are ‘a prescription for how to ruin a watershed,’ says former park chief.

Groundwater oozed from the edges of the roads, evaporating long before it could reach the river. Weeds flourished in the disturbed soil. Drill sites near the peak of the mountain, left by coal prospectors, were in disrepair. Industrial equipment was scattered haphazardly across the flat clearings near the switchbacks.

Van Tighem wasn’t surprised by the ramshackle state of the roads. He has led expeditions to the sites since 2020. Each year he finds the situation becomes “increasingly urgent, but also increasingly hopeless.”

He is the former superintendent of Banff National Park. Over the past three years, he has worked with locals in the Livingstone area, northwest of Pincher Creek, opposing mine development and exploratory roads.

“They are exposed to the elements and are eroding like crazy,” Van Tighem said.

“If you wanted to come up with a prescription for how to ruin a watershed, that is what Alberta has accomplished,” said Van Tighem, who ran in the last provincial election for the NDP and lost.

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the United Conservative Party gave a handful of Australian coal companies free rein over some parts of Alberta’s iconic Rockies and foothills. After a public outcry in which protest signs sprouted on front lawns across Alberta, the policy was hastily reinstated.

Deteriorating roads like these threaten a water supply that ‘supports the entire economy,’ says naturalist Kevin Van Tighem, one of many calling for remediation.

Photo via Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society.

The summer heat beat down on Kevin Van Tighem as he traced a steep dirt road up Cabin Ridge Mountain, deep in Alberta’s Rockies. This was no ordinary hike. Van Tighem was investigating the state of industrial coal roads, constructed years prior. As he neared the peak of Cabin Ridge, the signs of deterioration came into focus.

The summer heat beat down on Kevin Van Tighem as he traced a steep dirt road up Cabin Ridge Mountain, deep in Alberta’s Rockies. This was no ordinary hike. Van Tighem was investigating the state of industrial coal roads, constructed years prior. As he neared the peak of Cabin Ridge, the signs of deterioration came into focus.

Groundwater oozed from the edges of the roads, evaporating long before it could reach the river. Weeds flourished in the disturbed soil. Drill sites near the peak of the mountain, left by coal prospectors, were in disrepair. Industrial equipment was scattered haphazardly across the flat clearings near the switchbacks.

Van Tighem wasn’t surprised by the ramshackle state of the roads. He has led expeditions to the sites since 2020. Each year he finds the situation becomes “increasingly urgent, but also increasingly hopeless.”

He is the former superintendent of Banff National Park. Over the past three years, he has worked with locals in the Livingstone area, northwest of Pincher Creek, opposing mine development and exploratory roads.

“They are exposed to the elements and are eroding like crazy,” Van Tighem said.

“If you wanted to come up with a prescription for how to ruin a watershed, that is what Alberta has accomplished,” said Van Tighem, who ran in the last provincial election for the NDP and lost.

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the United Conservative Party gave a handful of Australian coal companies free rein over some parts of Alberta’s iconic Rockies and foothills. After a public outcry in which protest signs sprouted on front lawns across Alberta, the policy was hastily reinstated.

Kevin Van Tighem: Roads cut into mountain sides, then simply abandoned by investors, ‘are exposed to the elements and are eroding like crazy.’ Photo supplied.

Exploratory roads contain barriers for sediment control, but they have not been properly maintained.

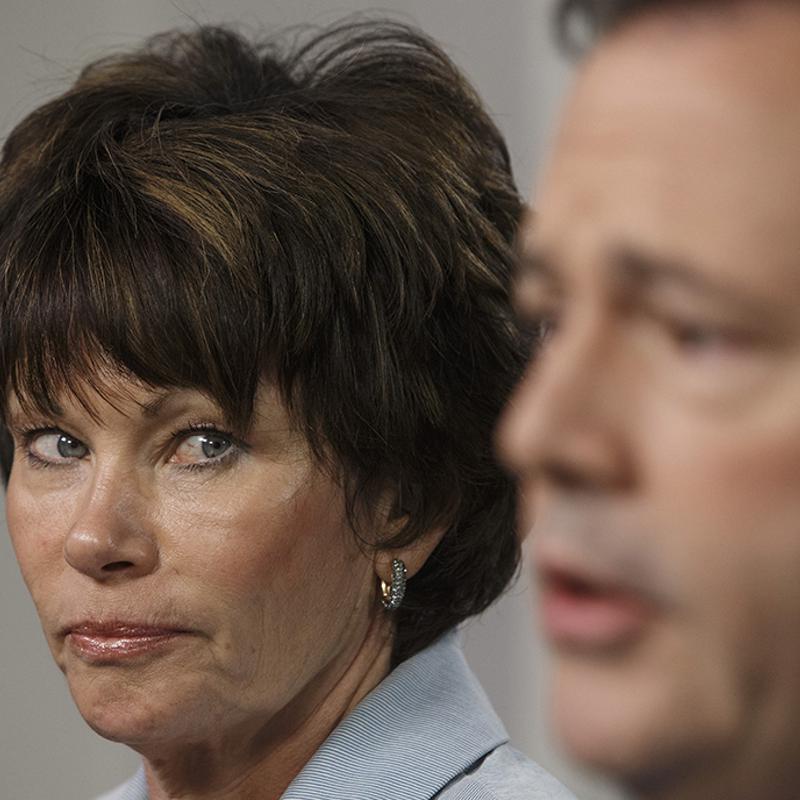

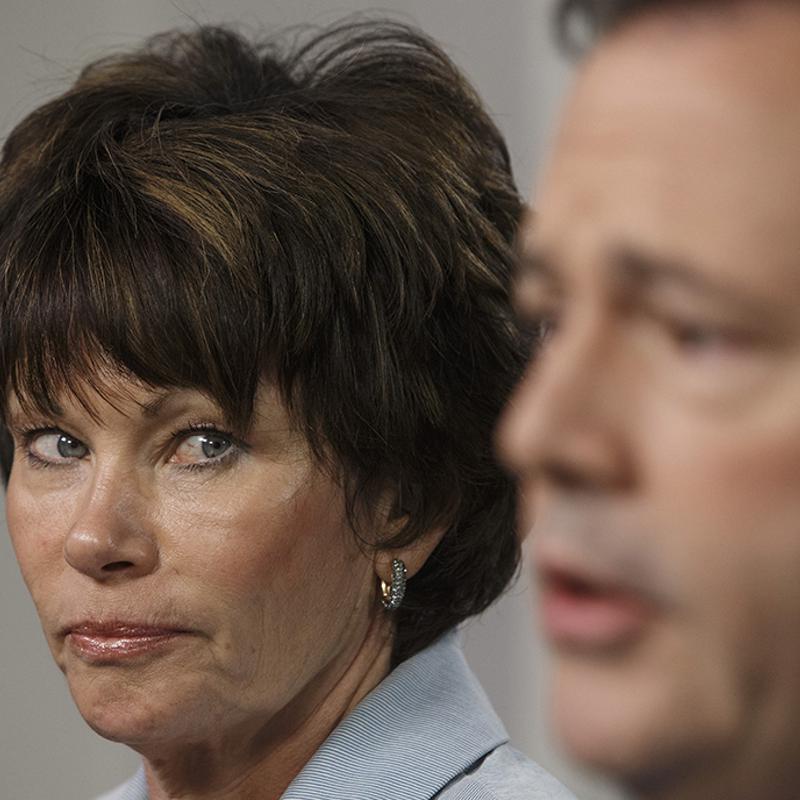

“They’re in disrepair,” Katie Morrison said. Morrison is president of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, or CPAWS, a conservation group.

“I don’t think the companies are out there actually upkeeping things like sediment control. It is very likely that in its absence we are seeing these sediment and stream diversion issues happening.”

Although no mines were built, the exploratory roads remain.

“Most of these companies are penny stock companies, they have no capital,” Van Tighem said.

“You can tell them to go back and clean it up and they will say, ‘With what? The investors walked away, the policy was brought in and we got no money.’”

“The resource will not be extracted, there will be no money made. All we have done is compromise another major resource which is our water supply. That water supply supports the entire economy,” Van Tighem said.

Alberta’s Coal Mining Reversal: These Tyee Pieces Tell the Tale

Exploratory roads contain barriers for sediment control, but they have not been properly maintained.

“They’re in disrepair,” Katie Morrison said. Morrison is president of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, or CPAWS, a conservation group.

“I don’t think the companies are out there actually upkeeping things like sediment control. It is very likely that in its absence we are seeing these sediment and stream diversion issues happening.”

Although no mines were built, the exploratory roads remain.

“Most of these companies are penny stock companies, they have no capital,” Van Tighem said.

“You can tell them to go back and clean it up and they will say, ‘With what? The investors walked away, the policy was brought in and we got no money.’”

“The resource will not be extracted, there will be no money made. All we have done is compromise another major resource which is our water supply. That water supply supports the entire economy,” Van Tighem said.

Alberta’s Coal Mining Reversal: These Tyee Pieces Tell the Tale

READ MORE

If left unattended, exploratory roads pose a number of potential negative environmental impacts. Soil layers are shallower in Alberta’s mountains and are easily disturbed. Natural plant life struggles to regrow, exposed sediment washes into rivers and reservoirs, and groundwater intersected by roads escapes early in the season and evaporates.

“We’re in a drought,” Van Tighem said. “Our rivers are shrunken down. Our reservoirs are empty. If it ever was obvious which is more important, water or coal, this is the year that we have the answer.”

Nestled in the mountains on Alberta’s border, the Oldman River headwaters — the location of a proposed mine — provide water to 45 per cent of Alberta. One fifth of Alberta’s agricultural production is irrigated agriculture, one reason it is critical to maintain a healthy watershed.

Coal exploratory roads quickly exceeded legal density limits. CPAWS found the government approved 448 kilometres of exploratory roads between 2018 and 2020.

“They certainly built extensive roads and drill site networks, but we don’t know exactly how many or where all of them are,” Morrison said.

If left unattended, exploratory roads pose a number of potential negative environmental impacts. Soil layers are shallower in Alberta’s mountains and are easily disturbed. Natural plant life struggles to regrow, exposed sediment washes into rivers and reservoirs, and groundwater intersected by roads escapes early in the season and evaporates.

“We’re in a drought,” Van Tighem said. “Our rivers are shrunken down. Our reservoirs are empty. If it ever was obvious which is more important, water or coal, this is the year that we have the answer.”

Nestled in the mountains on Alberta’s border, the Oldman River headwaters — the location of a proposed mine — provide water to 45 per cent of Alberta. One fifth of Alberta’s agricultural production is irrigated agriculture, one reason it is critical to maintain a healthy watershed.

Coal exploratory roads quickly exceeded legal density limits. CPAWS found the government approved 448 kilometres of exploratory roads between 2018 and 2020.

“They certainly built extensive roads and drill site networks, but we don’t know exactly how many or where all of them are,” Morrison said.

When the UCP government briefly opened sensitive areas of the Rocky Mountains to coal excavation, global firms swooped in. Public outcry made the government backtrack on mines, but the landscape is now riven with scenes like these of eroding roads and industrial remnants. Photos by Kevin Van Tighem.

The first time Morrison asked the government for detailed information about the density of road networks, the government said they hadn’t compiled the data. Morrison said the government now has completed the database, but won’t provide the data.

Native plant life uprooted by exploratory roads doesn’t regrow easily, as non-native plants and invasive species sprout in their place. Dedicated weed control is required to keep them in check. On a recent visit, Morrison found the sites “in disrepair.”

The Australian Invasion: Big Coal’s Plans for Alberta

The first time Morrison asked the government for detailed information about the density of road networks, the government said they hadn’t compiled the data. Morrison said the government now has completed the database, but won’t provide the data.

Native plant life uprooted by exploratory roads doesn’t regrow easily, as non-native plants and invasive species sprout in their place. Dedicated weed control is required to keep them in check. On a recent visit, Morrison found the sites “in disrepair.”

The Australian Invasion: Big Coal’s Plans for Alberta

READ MORE

“Until these are actually reclaimed, these roads are just going to sit there and we are going to continue having these water, wildlife and vegetation impacts on the landscape.”

Exploration permits granted to companies by the Alberta Energy Regulator have a five-year timeline. Companies are given two years to conduct exploration followed by three years reclaiming the sites. Unlike British Columbia, Alberta does not require a deposit from exploration companies before operations begin.

One of the Australian-based coal firms that built roads while prospecting in Alberta, Montem Resources, said they “intend to continue to reclaim and remediate areas on which it conducted exploratory activities in accordance with its coal exploration permits and other regulatory requirements.”

Minister of Energy and Minerals Brian Jean and the AER declined to respond to Tyee interview requests.

David Luff served in the government of former premier Peter Lougheed, and helped finalize the Coal Policy in 1976. He described the UCP’s revocation of the policy as “morally and ethically wrong.”

Critics Skeptical as Alberta Reverses Course on Open-pit Coal Mines

“Until these are actually reclaimed, these roads are just going to sit there and we are going to continue having these water, wildlife and vegetation impacts on the landscape.”

Exploration permits granted to companies by the Alberta Energy Regulator have a five-year timeline. Companies are given two years to conduct exploration followed by three years reclaiming the sites. Unlike British Columbia, Alberta does not require a deposit from exploration companies before operations begin.

One of the Australian-based coal firms that built roads while prospecting in Alberta, Montem Resources, said they “intend to continue to reclaim and remediate areas on which it conducted exploratory activities in accordance with its coal exploration permits and other regulatory requirements.”

Minister of Energy and Minerals Brian Jean and the AER declined to respond to Tyee interview requests.

David Luff served in the government of former premier Peter Lougheed, and helped finalize the Coal Policy in 1976. He described the UCP’s revocation of the policy as “morally and ethically wrong.”

Critics Skeptical as Alberta Reverses Course on Open-pit Coal Mines

READ MORE

“There was no consultation by the UCP with Indigenous communities whose treaty rights and Aboriginal rights are directly and adversely affected,” Luff said. “It was all done behind closed doors and the public was not aware of it.”

Former energy minister Sonya Savage reinstated the Coal Policy by ministerial order in February 2021. She created the Coal Policy Committee shortly after to consult the public on how coal development should proceed. The committee found 90 per cent of Albertans felt there were areas not appropriate for coal development, while 85 per cent were “not at all confident that coal development in Alberta is regulated to ensure it is environmentally sustainable.”

Luff said the fight over coal mining is far from over.

“Ministerial orders can be changed with the whim of the minister, or the direction of the premier. The next three to four months will be critical to understand exactly where this government is on coal,” Luff said.

“Danielle Smith was not the premier back then. She is now. We don’t know where she and her government will go. That uncertainty is over everything.”

“There was no consultation by the UCP with Indigenous communities whose treaty rights and Aboriginal rights are directly and adversely affected,” Luff said. “It was all done behind closed doors and the public was not aware of it.”

Former energy minister Sonya Savage reinstated the Coal Policy by ministerial order in February 2021. She created the Coal Policy Committee shortly after to consult the public on how coal development should proceed. The committee found 90 per cent of Albertans felt there were areas not appropriate for coal development, while 85 per cent were “not at all confident that coal development in Alberta is regulated to ensure it is environmentally sustainable.”

Luff said the fight over coal mining is far from over.

“Ministerial orders can be changed with the whim of the minister, or the direction of the premier. The next three to four months will be critical to understand exactly where this government is on coal,” Luff said.

“Danielle Smith was not the premier back then. She is now. We don’t know where she and her government will go. That uncertainty is over everything.”

Yesterday

The Tyee

Clayton Keim is a Calgary-based freelance journalist with an interest in the economy, social issues and Alberta politics. If you have any additional information on this story, contact them via email.

Clayton Keim is a Calgary-based freelance journalist with an interest in the economy, social issues and Alberta politics. If you have any additional information on this story, contact them via email.

No comments:

Post a Comment