James Cheng-Morris

·Freelance news writer, Yahoo UK

Updated Fri, 6 October 2023

Police remove a climate activist during a demonstration in The Hague, Netherlands, earlier this month. September this year was the hottest on record. (AFP via Getty Images)

In this era of climate change, we have become well accustomed to record-breaking temperatures.

It’s barely even a surprise when you see the Pope wading in, as he did earlier this week, to say the world is “collapsing” and “nearing breaking point” because of climate change.

But since his intervention, new figures have emerged which have really shocked scientists.

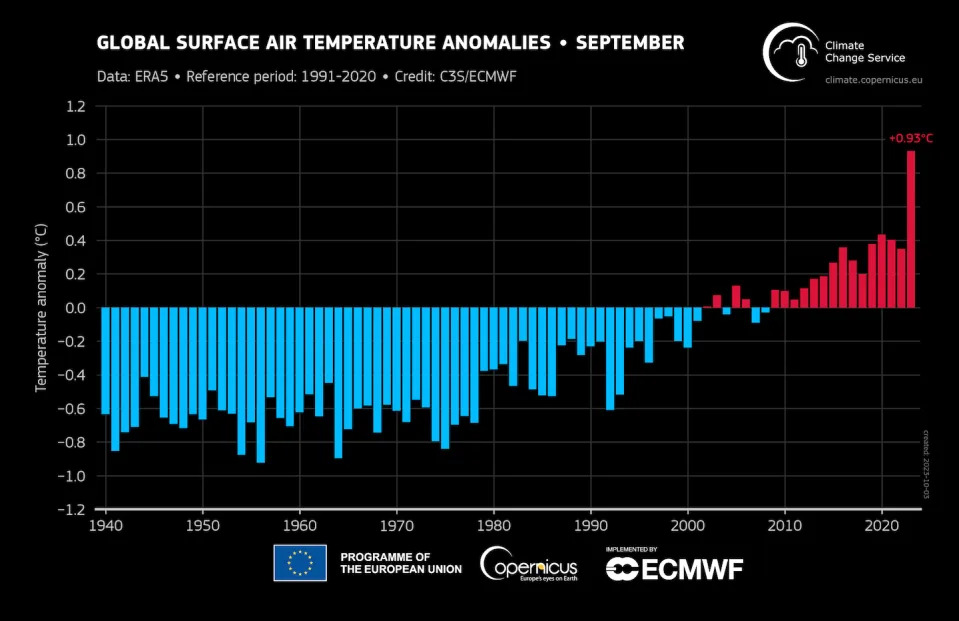

On Thursday, the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) released data showing last month was the hottest September, globally, since records began.

What has particularly stunned scientists, however, is that September’s temperatures were nearly 1C above the 1990 to 2020 average. A C3S chart demonstrating this, below, has gone viral on social media.

'The Age of Stupid’: Read more

Scientists shocked by September’s record-breaking heat (Evening Standard)

'The Age of Stupid': Stark warning from climate expert (Yahoo News UK)

What does the chart show?

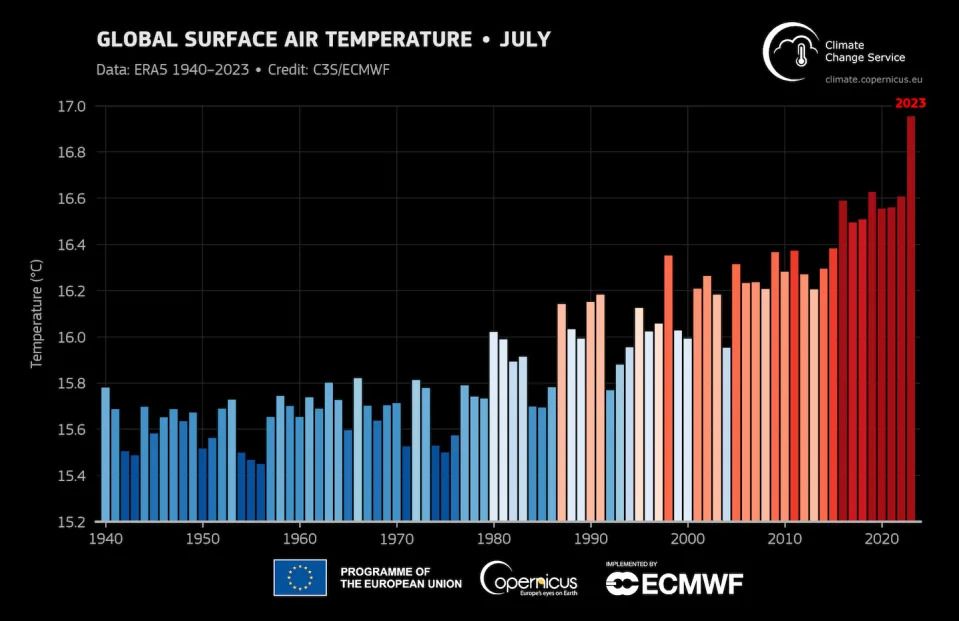

Surface air temperature rises between 1940 and 2023. (C3S)

In September, the average surface air temperature was 16.38C. This was 0.93C above the 1991 to 2020 average for the month of September.

It was also a massive 0.5C above the previous warmest September, in 2020, and 1.75C warmer than the pre-industrial average between 1850 and 1900.

Meanwhile, the global temperature for January to September this year was 0.52C higher than average, and 1.4C higher than the pre-industrial average.

There were also alarming statistics in Europe, where last month was the hottest ever September at 2.51C higher than the 1991 to 2020 average… and 1.1C higher than September 2020, the previous hottest.

All this comes after C3S released an analysis last month showing summer 2023 was the hottest ever. It prompted Prof David Reay, executive director of the Edinburgh Climate Change Institute, to say even climate sceptics “must now be wondering why their butts are so very hot”.

Here Yahoo News breaks down some of the opinions climate scientists have shared since the data came out.

'Gobsmackingly bananas'

Prominent climate scientist Zeke Hausfather posted on X, formerly known as Twitter: "This month [September] was, in my professional opinion as a climate scientist - absolutely gobsmackingly bananas."

'COP28 will be critical'

Samantha Burgess, deputy director of C3S, said: "The unprecedented temperatures for the time of year observed in September, following a record summer, have broken records by an extraordinary amount. Two months out from COP28, the sense of urgency for ambitious climate action has never been more critical.”

The UAE is host of this year’s COP summit, something which has been called into question given its plans to increase fossil fuel production and consumption.

What is more, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company - one of the world's biggest oil companies - is leading the talks. The UAE has a stated aim to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Pedestrians in Westminster, London, during a heatwave last month. (AFP via Getty Images)

'Surprising. Astounding. Staggering'

Prof Ed Hawkins, professor of climate science at the University of Reading, posted on X: "Surprising. Astounding. Staggering. Unnerving. Bewildering. Flabbergasting. Disquieting. Gobsmacking. Shocking. Mind-boggling."

'Anomalies are enormous'

Prof Petteri Taalas, secretary-general of the World Meteorological Organisation, said: “Since June, the world has experienced unprecedented heat on land and sea. The temperature anomalies are enormous, far bigger than anything we have ever seen in the past. Antarctic winter sea ice extent was the lowest on record for the time of year.

"What is especially worrying is that the warming El Nino event is still developing, and so we can expect these record-breaking temperatures to continue for months, with cascading impacts on our environment and society.”

'A death sentence'

Dr Friederike Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change, told Euronews: "This is not a fancy weather statistic. It’s a death sentence for people and ecosystems. It destroys assets, infrastructure, harvest.”

Global temperatures are off the charts for a reason: 4 factors driving 2023's extreme heat and climate disasters

Michael Wysession, Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

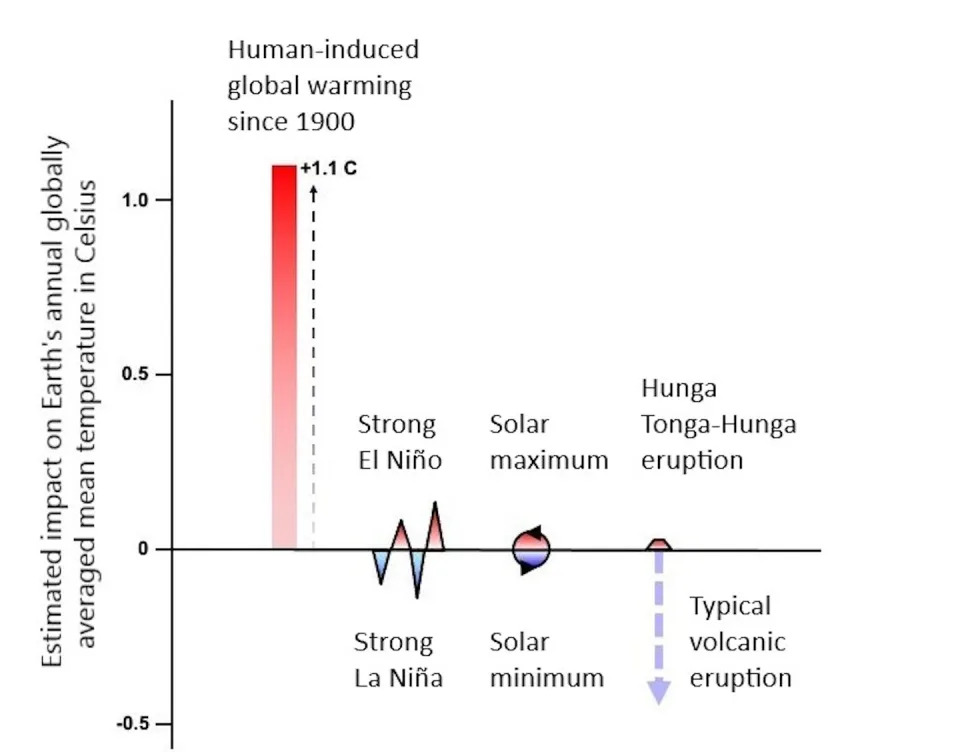

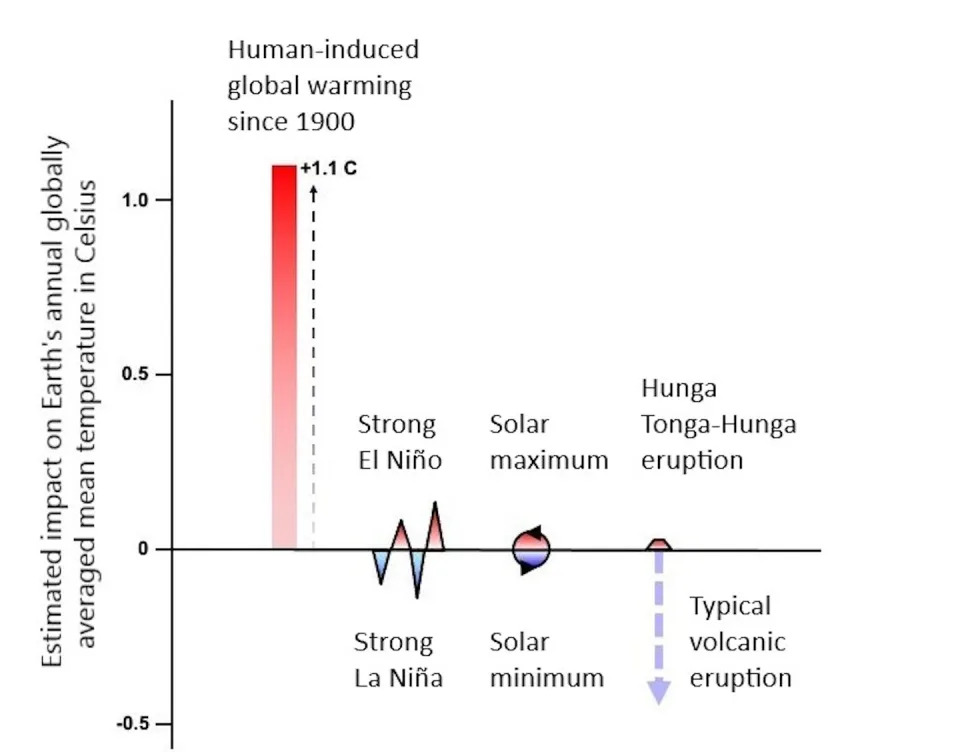

An illustration by the author shows the typical relative impact on temperature rise driven by human activities compared with natural forces. El Niño/La Niña and solar energy cycles fluctuate. The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano’s underwater eruption exacerbated global warming. Michael Wysession

How El Niño is involved

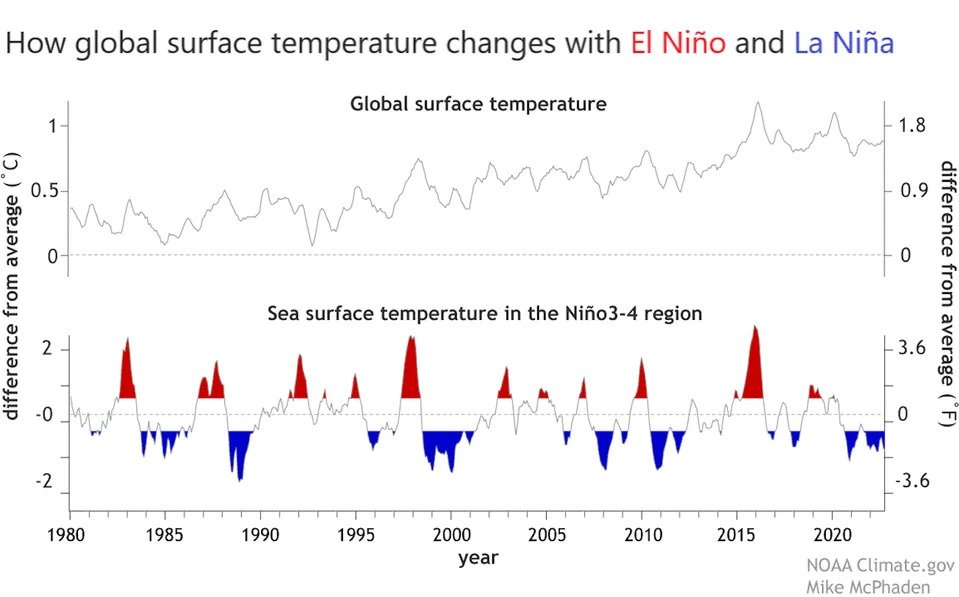

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that occurs every few years when surface water in the tropical Pacific reverses direction and heats up. That warms the atmosphere above, which influences temperatures and weather patterns around the globe.

Essentially, the atmosphere borrows heat out of the Pacific, and global temperatures increase slightly. This happened in 2016, the time of the last strong El Niño. Global temperatures increased by about 0.25 F (0.14 C) on average, making 2016 the warmest year on record. A weak El Niño also occurred in 2019-2020, contributing to 2020 becoming the world’s second-warmest year.

El Niño’s opposite, La Niña, involves cooler-than-usual Pacific currents flowing westward, absorbing heat out of the atmosphere, which cools the globe. The world just came out of three straight years of La Niña, meaning we’re experiencing an even greater temperature swing

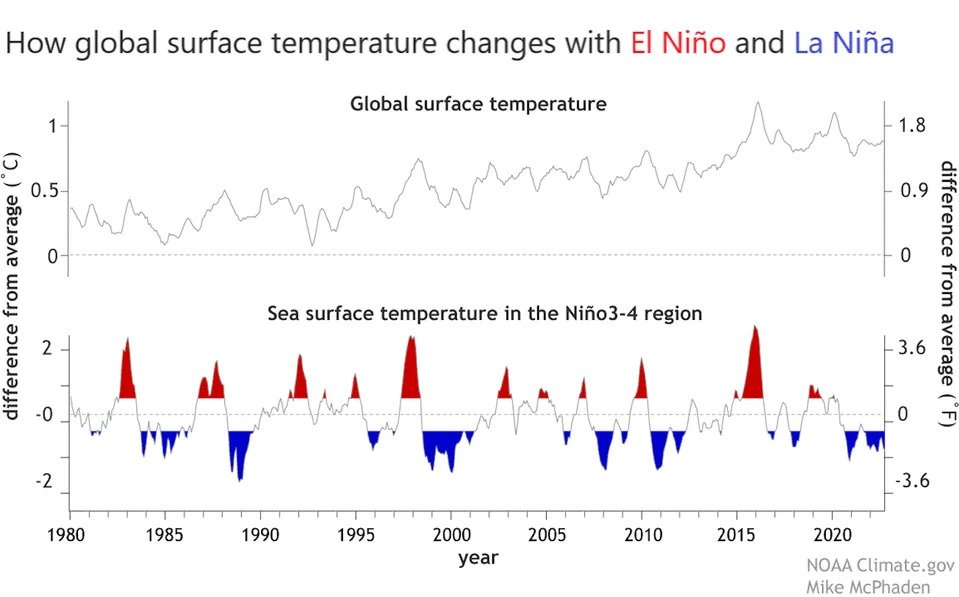

Comparing global temperatures (top chart) with El Niño and La Niña events. NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center

Based on increasing Pacific sea surface temperatures in mid-2023, climate modeling now suggests a 90% chance that Earth is headed toward its first strong El Niño since 2016.

Combined with the steady human-induced warming, Earth may soon again be breaking its annual temperature records. June 2023 was the hottest in modern record. July saw global records for the hottest days and a large number of regional records, including an incomprehensible heat index of 152 F (67 C) in Iran.

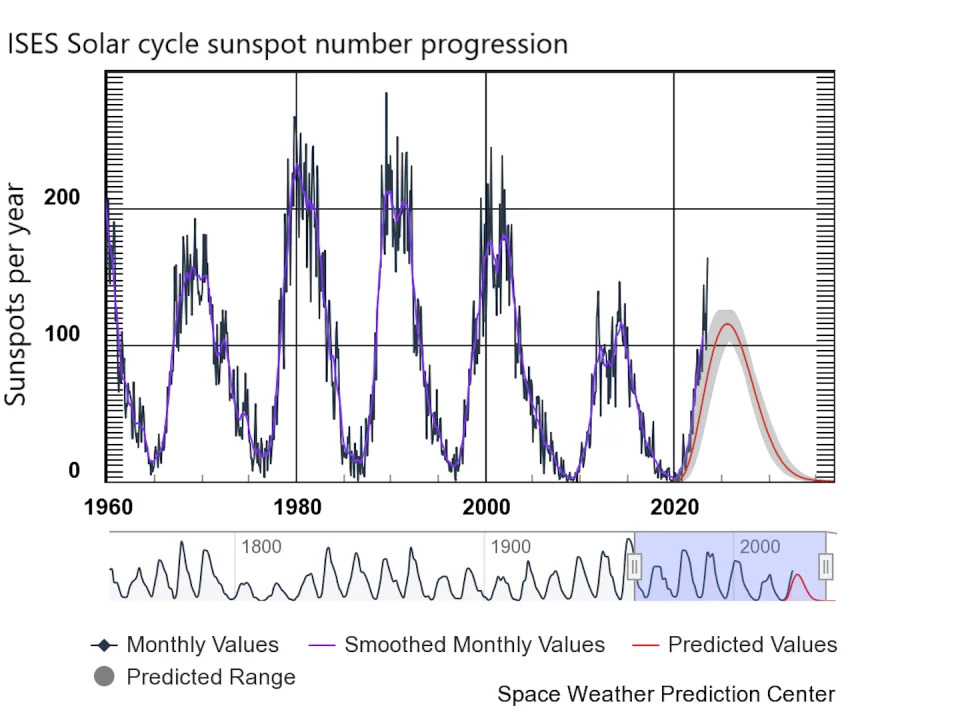

Solar fluctuations

The Sun may seem to shine at a constant rate, but it is a seething, churning ball of plasma whose radiating energy changes over many different time scales.

The Sun is slowly heating up and in half a billion years will boil away Earth’s oceans. On human time scales, however, the Sun’s energy output varies only slightly, about 1 part in 1,000, over a repeating 11-year cycle. The peaks of this cycle are too small for us to notice at a daily level, but they affect Earth’s climate systems.

Rapid convection within the Sun both generates a strong magnetic field aligned with its spin axis and causes this field to fully flip and reverse every 11 years. This is what causes the 11-year cycle in emitted solar radiation.

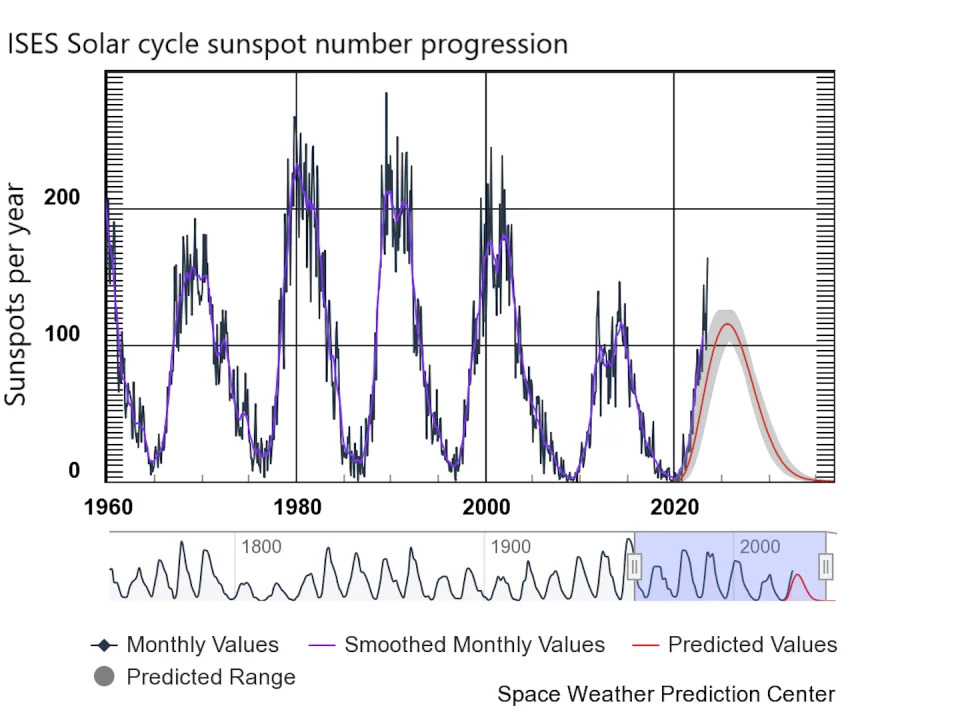

Sunspot activity is considered a proxy for the Sun’s energy output. The last 11-year solar cycle was unusually weak. The current cycle isn’t yet at its maximum. NOAA Space Weather Prediction CenterMore

Earth’s temperature increase during a solar maximum, compared with average solar output, is only about 0.09 F (0.05 C), roughly a third of a large El Niño. The opposite happens during a solar minimum. However, unlike the variable and unpredictable El Niño changes, the 11-year solar cycle is comparatively regular, consistent and predictable.

The last solar cycle hit its minimum in 2020, reducing the effect of the modest 2020 El Niño. The current solar cycle has already surpassed the peak of the relatively weak previous cycle (which was in 2014) and will peak in 2025, with the Sun’s energy output increasing until then.

A massive volcanic eruption

Volcanic eruptions can also significantly affect global climates. They usually do this by lowering global temperatures when erupted sulfate aerosols shield and block a portion of incoming sunlight – but not always.

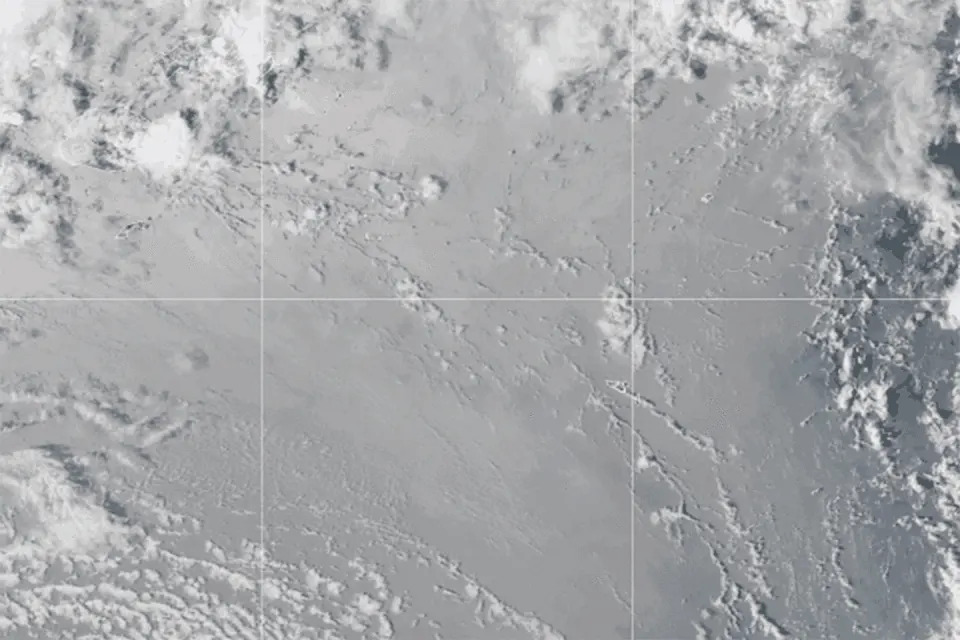

In an unusual twist, the largest volcanic eruption of the 21st century so far, the 2022 eruption of Tonga’s Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, is having a warming and not cooling effect.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano’s eruption was enormous, but underwater. It hurled large amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens using GOES imagery courtesy of NOAA and NESDISMore

The eruption released an unusually small amount of cooling sulfate aerosols but an enormous amount of water vapor. The molten magma exploded underwater, vaporizing a huge volume of ocean water that erupted like a geyser high into the atmosphere.

Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas, and the eruption may end up warming Earth’s surface by about 0.06 F (0.035 C), according to one estimate. Unlike the cooling sulfate aerosols, which are actually tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that fall out of the atmosphere within one to two years, water vapor is a gas that can stay in the atmosphere for many years. The warming impact of the Tonga volcano is expected to last for at least five years.

Underlying it all: Global warming

All of this comes on top of anthropogenic, or human-caused, global warming.

Humans have raised global average temperatures by about 2 F (1.1 C) since 1900 by releasing large volumes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is up 50%, primarily from the combustion of fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants. The warming from greenhouse gases is actually greater than 2 F (1.1 C), but it has been masked by other human factors that have a cooling effect, such as air pollution.

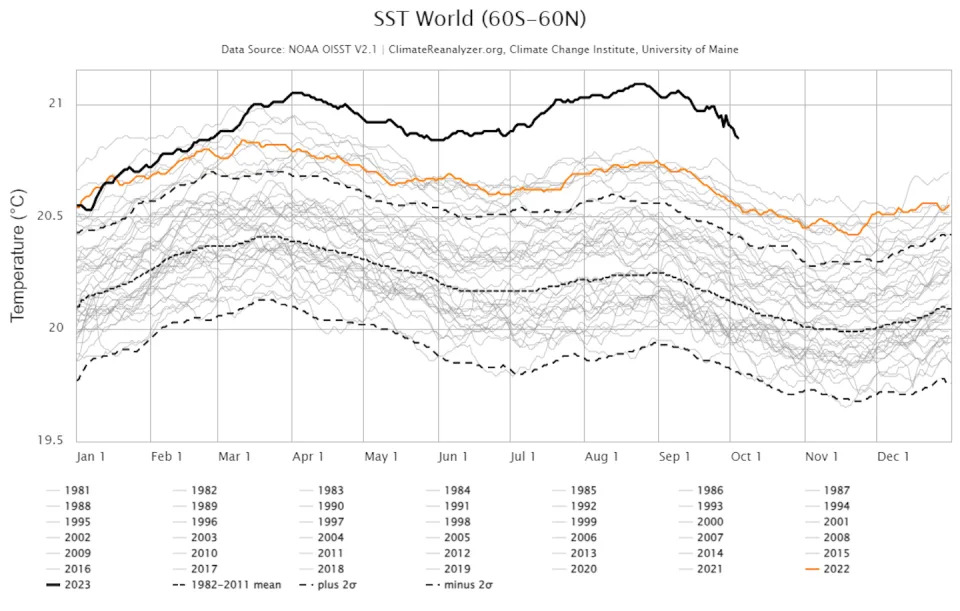

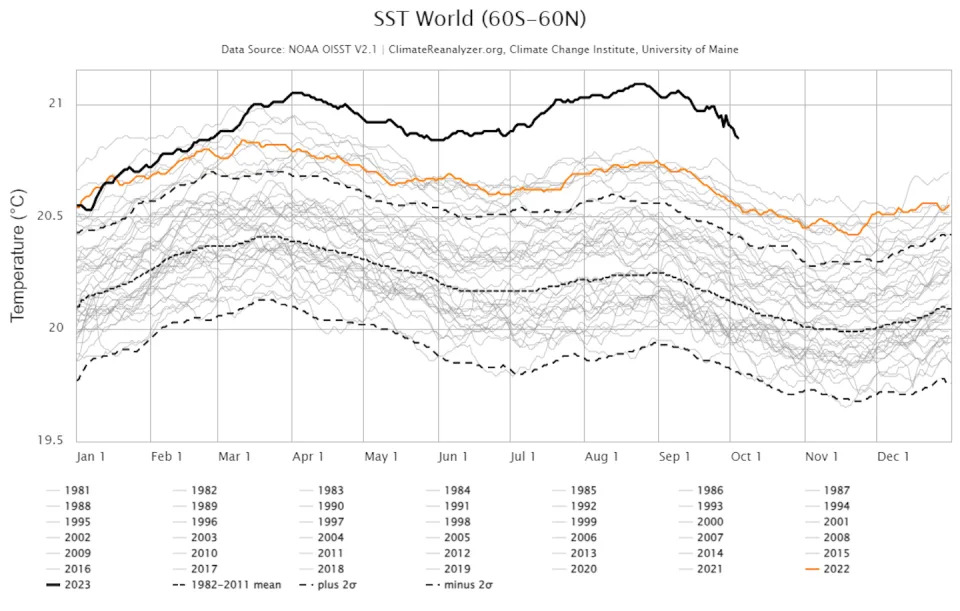

Sea surface temperatures in 2023 (bold black line) have been far above any temperature seen since satellite records began in the 1970s. University of Maine Climate Change Institute, CC BY-NDMore

If human impacts were the only factors, each successive year would set a new record as the hottest year ever, but that doesn’t happen. The year 2016 was the warmest in part because temperatures were boosted by the last large El Niño.

What does this mean for the future?

The next couple of years could be very rough.

If a strong El Niño develops over the coming months as forecasters expect, combined with the solar maximum and the effects of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption, Earth’s temperatures will likely continue to soar.

As temperatures continue to increase, weather events can get more extreme. The excess heat can mean more heat waves, forest fires, flash floods and other extreme weather events, climate models show.

A heavy downpour flooded streets across the New York City region, shutting down subways, schools and businesses on Sept. 29, 2023. AP Photo/Jake OffenhartzMore

In January 2023, scientists wrote that Earth’s temperature had a greater than 50% chance of reaching 2.7 F (1.5 C) above preindustrial era temperatures by the year 2028, at least temporarily, increasing the risk of triggering climate tipping points with even greater human impacts. Because of the unfortunate timing of several parts of the climate system, it seems the odds are not in our favor.

This article, originally published July 27, 2023, has been updated with September’s record heat.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

It was written by: Michael Wysession, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Read more:

Extreme heat is particularly hard on older adults – an aging population and climate change put ever more people at risk

How well-managed dams and smart forecasting can limit flooding as extreme storms become more common in a warming world

Dangerous urban heat exposure has tripled since the 1980s, with the poor most at risk

Michael Wysession, Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

THE CONVERSATION

Fri, October 6, 2023

2023's weather has been extreme in many ways. AP Photo/Michael Probst

Between the record-breaking global heat and extreme downpours, it’s hard to ignore that something unusual is going on with the weather in 2023.

People have been quick to blame climate change – and they’re right: Human-caused global warming does play the biggest role. For example, a study determined that the weekslong heat wave in Texas, the U.S. Southwest and Mexico that started in June 2023 would have been virtually impossible without it.

However, the extremes this year are sharper than anthropogenic global warming alone would be expected to cause. September temperatures were far above any previous September, and around 3.1 degrees Fahrenheit (1.75 degrees Celsius) above the preindustrial average, according to the European Union’s earth observation program.

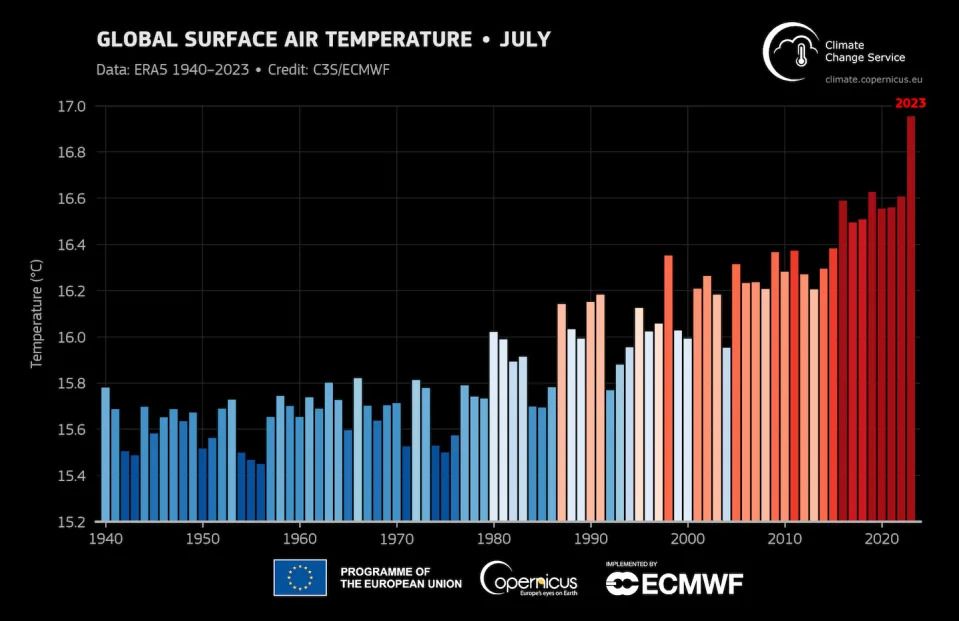

July was Earth’s hottest month on record, also by a large margin, with average global temperatures more than half a degree Fahrenheit (a third of a degree Celsius) above the previous record, set just a few years earlier in 2019.

September 2023’s temperatures were far above past Septembers. Copernicus

July 2023 was the hottest month on record and well above past Julys. Copernicus Climate Change Service

Human activities have been increasing temperatures at an average of about 0.2 F (0.1 C) per decade. But this year, three additional natural factors are also helping drive up global temperatures and fuel disasters: El Niño, solar fluctuations and a massive underwater volcanic eruption.

Unfortunately, these factors are combining in a way that is exacerbating global warming. Still worse, we can expect unusually high temperatures to continue, which means even more extreme weather in the near future

Fri, October 6, 2023

2023's weather has been extreme in many ways. AP Photo/Michael Probst

Between the record-breaking global heat and extreme downpours, it’s hard to ignore that something unusual is going on with the weather in 2023.

People have been quick to blame climate change – and they’re right: Human-caused global warming does play the biggest role. For example, a study determined that the weekslong heat wave in Texas, the U.S. Southwest and Mexico that started in June 2023 would have been virtually impossible without it.

However, the extremes this year are sharper than anthropogenic global warming alone would be expected to cause. September temperatures were far above any previous September, and around 3.1 degrees Fahrenheit (1.75 degrees Celsius) above the preindustrial average, according to the European Union’s earth observation program.

July was Earth’s hottest month on record, also by a large margin, with average global temperatures more than half a degree Fahrenheit (a third of a degree Celsius) above the previous record, set just a few years earlier in 2019.

September 2023’s temperatures were far above past Septembers. Copernicus

July 2023 was the hottest month on record and well above past Julys. Copernicus Climate Change Service

Human activities have been increasing temperatures at an average of about 0.2 F (0.1 C) per decade. But this year, three additional natural factors are also helping drive up global temperatures and fuel disasters: El Niño, solar fluctuations and a massive underwater volcanic eruption.

Unfortunately, these factors are combining in a way that is exacerbating global warming. Still worse, we can expect unusually high temperatures to continue, which means even more extreme weather in the near future

An illustration by the author shows the typical relative impact on temperature rise driven by human activities compared with natural forces. El Niño/La Niña and solar energy cycles fluctuate. The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano’s underwater eruption exacerbated global warming. Michael Wysession

How El Niño is involved

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that occurs every few years when surface water in the tropical Pacific reverses direction and heats up. That warms the atmosphere above, which influences temperatures and weather patterns around the globe.

Essentially, the atmosphere borrows heat out of the Pacific, and global temperatures increase slightly. This happened in 2016, the time of the last strong El Niño. Global temperatures increased by about 0.25 F (0.14 C) on average, making 2016 the warmest year on record. A weak El Niño also occurred in 2019-2020, contributing to 2020 becoming the world’s second-warmest year.

El Niño’s opposite, La Niña, involves cooler-than-usual Pacific currents flowing westward, absorbing heat out of the atmosphere, which cools the globe. The world just came out of three straight years of La Niña, meaning we’re experiencing an even greater temperature swing

Comparing global temperatures (top chart) with El Niño and La Niña events. NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center

Based on increasing Pacific sea surface temperatures in mid-2023, climate modeling now suggests a 90% chance that Earth is headed toward its first strong El Niño since 2016.

Combined with the steady human-induced warming, Earth may soon again be breaking its annual temperature records. June 2023 was the hottest in modern record. July saw global records for the hottest days and a large number of regional records, including an incomprehensible heat index of 152 F (67 C) in Iran.

Solar fluctuations

The Sun may seem to shine at a constant rate, but it is a seething, churning ball of plasma whose radiating energy changes over many different time scales.

The Sun is slowly heating up and in half a billion years will boil away Earth’s oceans. On human time scales, however, the Sun’s energy output varies only slightly, about 1 part in 1,000, over a repeating 11-year cycle. The peaks of this cycle are too small for us to notice at a daily level, but they affect Earth’s climate systems.

Rapid convection within the Sun both generates a strong magnetic field aligned with its spin axis and causes this field to fully flip and reverse every 11 years. This is what causes the 11-year cycle in emitted solar radiation.

Sunspot activity is considered a proxy for the Sun’s energy output. The last 11-year solar cycle was unusually weak. The current cycle isn’t yet at its maximum. NOAA Space Weather Prediction CenterMore

Earth’s temperature increase during a solar maximum, compared with average solar output, is only about 0.09 F (0.05 C), roughly a third of a large El Niño. The opposite happens during a solar minimum. However, unlike the variable and unpredictable El Niño changes, the 11-year solar cycle is comparatively regular, consistent and predictable.

The last solar cycle hit its minimum in 2020, reducing the effect of the modest 2020 El Niño. The current solar cycle has already surpassed the peak of the relatively weak previous cycle (which was in 2014) and will peak in 2025, with the Sun’s energy output increasing until then.

A massive volcanic eruption

Volcanic eruptions can also significantly affect global climates. They usually do this by lowering global temperatures when erupted sulfate aerosols shield and block a portion of incoming sunlight – but not always.

In an unusual twist, the largest volcanic eruption of the 21st century so far, the 2022 eruption of Tonga’s Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, is having a warming and not cooling effect.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano’s eruption was enormous, but underwater. It hurled large amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens using GOES imagery courtesy of NOAA and NESDISMore

The eruption released an unusually small amount of cooling sulfate aerosols but an enormous amount of water vapor. The molten magma exploded underwater, vaporizing a huge volume of ocean water that erupted like a geyser high into the atmosphere.

Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas, and the eruption may end up warming Earth’s surface by about 0.06 F (0.035 C), according to one estimate. Unlike the cooling sulfate aerosols, which are actually tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that fall out of the atmosphere within one to two years, water vapor is a gas that can stay in the atmosphere for many years. The warming impact of the Tonga volcano is expected to last for at least five years.

Underlying it all: Global warming

All of this comes on top of anthropogenic, or human-caused, global warming.

Humans have raised global average temperatures by about 2 F (1.1 C) since 1900 by releasing large volumes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is up 50%, primarily from the combustion of fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants. The warming from greenhouse gases is actually greater than 2 F (1.1 C), but it has been masked by other human factors that have a cooling effect, such as air pollution.

Sea surface temperatures in 2023 (bold black line) have been far above any temperature seen since satellite records began in the 1970s. University of Maine Climate Change Institute, CC BY-NDMore

If human impacts were the only factors, each successive year would set a new record as the hottest year ever, but that doesn’t happen. The year 2016 was the warmest in part because temperatures were boosted by the last large El Niño.

What does this mean for the future?

The next couple of years could be very rough.

If a strong El Niño develops over the coming months as forecasters expect, combined with the solar maximum and the effects of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption, Earth’s temperatures will likely continue to soar.

As temperatures continue to increase, weather events can get more extreme. The excess heat can mean more heat waves, forest fires, flash floods and other extreme weather events, climate models show.

A heavy downpour flooded streets across the New York City region, shutting down subways, schools and businesses on Sept. 29, 2023. AP Photo/Jake OffenhartzMore

In January 2023, scientists wrote that Earth’s temperature had a greater than 50% chance of reaching 2.7 F (1.5 C) above preindustrial era temperatures by the year 2028, at least temporarily, increasing the risk of triggering climate tipping points with even greater human impacts. Because of the unfortunate timing of several parts of the climate system, it seems the odds are not in our favor.

This article, originally published July 27, 2023, has been updated with September’s record heat.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

It was written by: Michael Wysession, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Read more:

Extreme heat is particularly hard on older adults – an aging population and climate change put ever more people at risk

How well-managed dams and smart forecasting can limit flooding as extreme storms become more common in a warming world

Dangerous urban heat exposure has tripled since the 1980s, with the poor most at risk

No comments:

Post a Comment