Christopher Schaberg on the rapids of rhetoric, the sandbars of routine and the depths of experience.

By Liam Otten October 16, 2023

Christopher Schaberg and his son, Julien, at the Boat House in Forest Park. (Photo: Danny Reise/Washington University)

Christopher Schaberg and his son, Julien, at the Boat House in Forest Park. (Photo: Danny Reise/Washington University)“Don’t expect a straightforward narrative in this book. Adventure doesn’t work like that.”

— Christopher Schaberg

Shopping. Driving. Parenting. Eating out. Working out. Going online.

For the contemporary consumer, the sources of potential adventure are as limitless as a marketer’s imagination. No activity is too mundane, no product too crass, no invocation too preposterous.

“Working on this book, I told my kids, anytime you see the word ‘adventure,’ let me know,” Christopher Schaberg says. “That’s often the way I write. I’ll collect cultural artifacts and ask, what do these things mean?”

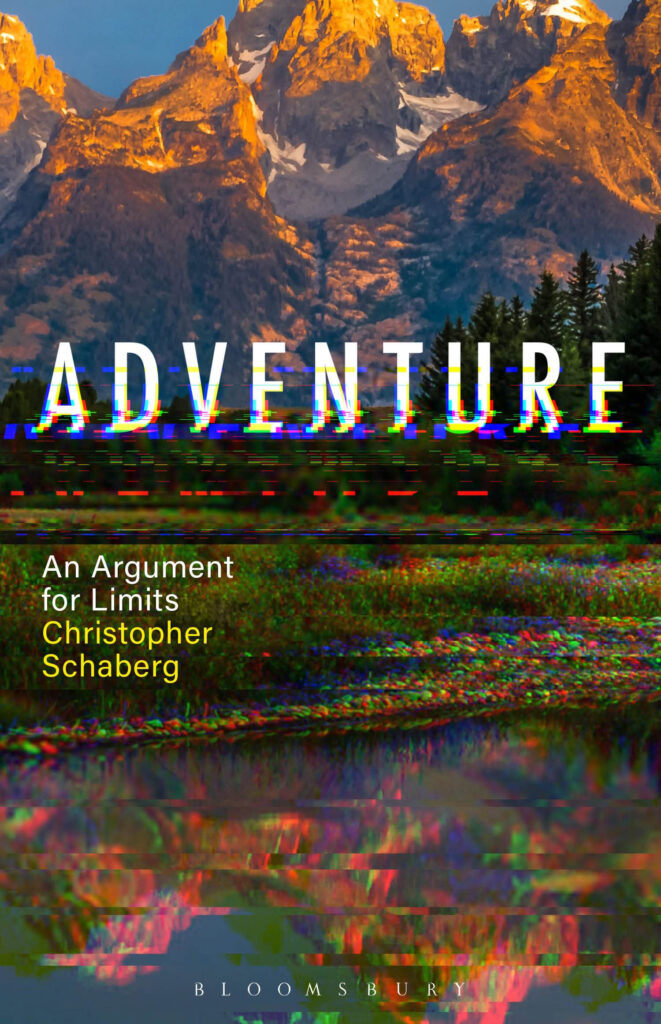

Schaberg, who recently came to Washington University in St. Louis as Arts & Sciences’ director of public scholarship, is discussing his latest collection, Adventure: An Argument for Limits. Released in August by Bloomsbury Academic, the book grapples with classical conceptions of adventure and their 21st-century simulacra while also asking, in all earnestness: What constitutes adventure today?

“Looking back, I realize that a lot of what I’ve written is really about adventure,” says Schaberg, whose previous publications include four volumes on air travel as well as books about fly-fishing, ecology, university life and the contemporary role of the humanities.

“Traditionally, we think about adventure as a solo pursuit or an individual achievement,” Schaberg says. “But today, culturally speaking, the real adventures are collective and planetary. They’re about confronting ecological disaster or systematic injustice.

“Adventure needs an updating.

”

Schaberg and Julien out on the water. (Photo: Danny Reise/Washington University)

‘A Little Adventure Everywhere’

As a college student, Schaberg worked a variety of outdoor jobs: river guide, ski-lift operator, airport “cross-utilized agent” (a title that still delights him). He describes reading Jack Kerouac’s novel Big Sur on a mountain during a power outage and piloting boats through Wyoming’s Grand Tetons.

“It was exciting,” he says of the latter. “But after dozens and then hundreds of trips, it just became my job. I was supplying an experience. In a lot of ways, this book was about revisiting those years, and trying to locate the point where adventure becomes routine — or a consumer product.”

Schaberg is attentive to how language shapes perceptions. In the opening section, “A Little Adventure Everywhere,” he contrasts the excesses of adventure-themed advertising (the kids found some howlers) with the term’s still-potent motivational capacity — the way it “raises the stakes for the day and makes potentially anything a little more exciting.”

“For so many adventures, the action is in the interpretation,” he writes. “The discovery is textual.”

Schaberg also makes a case for embracing limits, both linguistic and logistical. Not every meal is a culinary adventure, and not every constraint is a barrier. Harkening back to Wyoming, “it strikes me that a river is a good definition of a limit case for adventure: currents, shifting banks and sand bars, water levels, and channels all determine the course of water and how one can — and can’t — travel down (or sometimes up) a river.

“A successful river trip is a respectful exercise in limits. As such, it’s an object lesson for adventure.”

As a college student, Schaberg worked a variety of outdoor jobs: river guide, ski-lift operator, airport “cross-utilized agent” (a title that still delights him). He describes reading Jack Kerouac’s novel Big Sur on a mountain during a power outage and piloting boats through Wyoming’s Grand Tetons.

“It was exciting,” he says of the latter. “But after dozens and then hundreds of trips, it just became my job. I was supplying an experience. In a lot of ways, this book was about revisiting those years, and trying to locate the point where adventure becomes routine — or a consumer product.”

Schaberg is attentive to how language shapes perceptions. In the opening section, “A Little Adventure Everywhere,” he contrasts the excesses of adventure-themed advertising (the kids found some howlers) with the term’s still-potent motivational capacity — the way it “raises the stakes for the day and makes potentially anything a little more exciting.”

“For so many adventures, the action is in the interpretation,” he writes. “The discovery is textual.”

Schaberg also makes a case for embracing limits, both linguistic and logistical. Not every meal is a culinary adventure, and not every constraint is a barrier. Harkening back to Wyoming, “it strikes me that a river is a good definition of a limit case for adventure: currents, shifting banks and sand bars, water levels, and channels all determine the course of water and how one can — and can’t — travel down (or sometimes up) a river.

“A successful river trip is a respectful exercise in limits. As such, it’s an object lesson for adventure.”

Exploring the shoreline. (Photo: Dannny Reise/Washington University)

‘The Ends of Adventure’

Schaberg moved frequently as a child, but prior to arriving at WashU, he spent more than a decade at Loyola University. In the section “Nowhere Else,” he recounts the adventures of everyday life in New Orleans, including buying a house, starting a family, bicycling with his daughter and, during COVID lockdowns, fly fishing in the canals.

“I look back over these years, trying to piece together this adventure in distended diary form,” he writes. “The limit on adventure here is the mundane, the living in a place through time.”

“Final Frontiers” tackles adventures of the techno-utopian variety. “Adventure is a word that can motivate or inspire, but it’s also a word that can be used to justify various enterprises — often really unjust and exploitative ones,” he writes. “Increasingly, these enterprises have to do with space travel and all the attendant and often contradictory fantasies therein.”

In the book’s final section, “The Ends of Adventure,” Schaberg confronts two questions: Where do we find adventure now? And how are desires for adventure linked to environmental awareness?

Jumping from philosophers Giorgio Agamben and Bruno Latour to poets Claudia Rankine and Ross Gay to a recent catalog from outdoor clothier Orvis, Schaberg unpacks how the will to adventure can elide social hierarchies, rationalize hidden labor — often by those who themselves cannot afford to participate — and excuse ecological entitlement.

“The ends, or purpose, of adventure now should be to work toward a more just society, on a planet that miraculously sustains us,” Schaberg concludes. “This means not abandoning Earth — sorry, Elon Musk — but recommitting to it.”

Post-Dispatch Lake (Photo: Danny Reise/Washington University)

No comments:

Post a Comment