Story by Nora Eckert • The Wall Street Journal

LONG READ

In hard-nosed negotiations, the United Auto Workers in recent weeks shocked Detroit automakers with public swipes at CEO pay, a renewed focus on the rank-and-file and a bold plan for sudden strikes. The aggressive strategy was driven by a band of young outsiders—who have never clocked in a day of work at an auto factory.

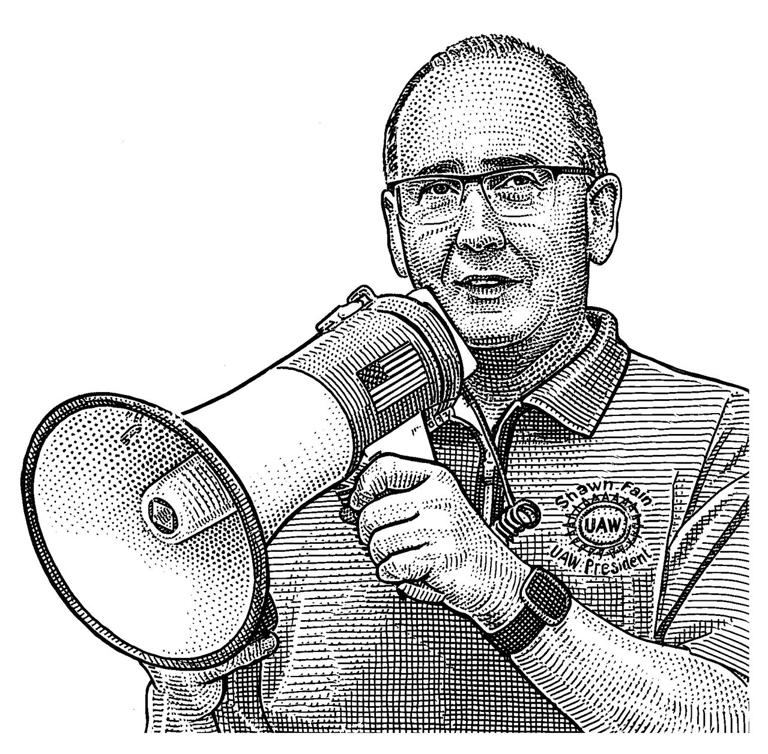

The three 30-something labor activists were brought in by new UAW President Shawn Fain to remake the union into a more independent, media savvy and creative challenger to car companies.

They included a communications specialist who helped craft campaigns for Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a New York labor attorney who once wrote on progressive labor issues and a former reporter who later would help win major concessions from the New York Times for the NewsGuild of New York.

At the UAW, one of the country’s largest unions, they were given a national platform during one of the most active years for strikes in nearly a generation. The result was a sharper and more bitter collective-bargaining battle with Detroit—and one of the biggest wins in decades.

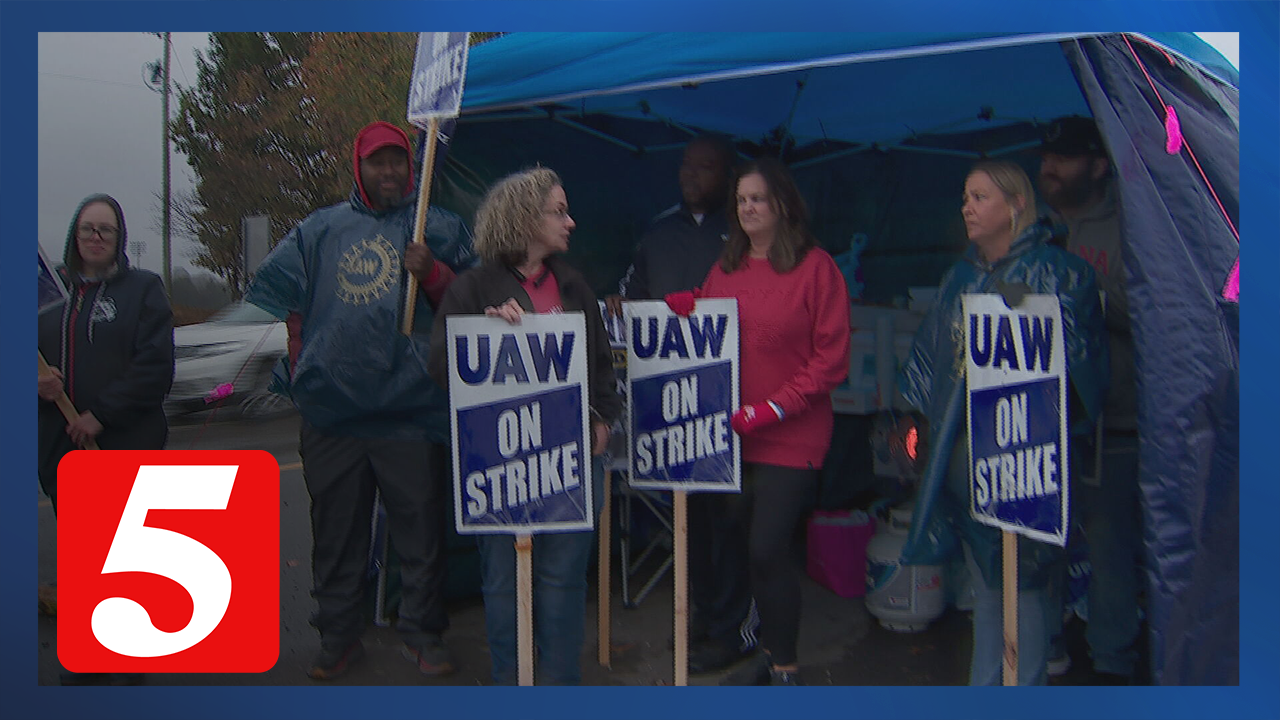

After a more than six-week strike that put 45,000 workers on the picket lines, the UAW came to tentative deals with Ford, Chrysler-parent Stellantis and General Motors that increase wages 25% over 4½ years—more than the total increase in the past 22 years—plus the return of cost-of-living adjustments. The contracts are the most lucrative since the 1960s, union leaders said.

In hard-nosed negotiations, the United Auto Workers in recent weeks shocked Detroit automakers with public swipes at CEO pay, a renewed focus on the rank-and-file and a bold plan for sudden strikes. The aggressive strategy was driven by a band of young outsiders—who have never clocked in a day of work at an auto factory.

The three 30-something labor activists were brought in by new UAW President Shawn Fain to remake the union into a more independent, media savvy and creative challenger to car companies.

They included a communications specialist who helped craft campaigns for Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a New York labor attorney who once wrote on progressive labor issues and a former reporter who later would help win major concessions from the New York Times for the NewsGuild of New York.

At the UAW, one of the country’s largest unions, they were given a national platform during one of the most active years for strikes in nearly a generation. The result was a sharper and more bitter collective-bargaining battle with Detroit—and one of the biggest wins in decades.

After a more than six-week strike that put 45,000 workers on the picket lines, the UAW came to tentative deals with Ford, Chrysler-parent Stellantis and General Motors that increase wages 25% over 4½ years—more than the total increase in the past 22 years—plus the return of cost-of-living adjustments. The contracts are the most lucrative since the 1960s, union leaders said.

Related video: GM, UAW reach tentative deal, sources say (FOX 2 Detroit)

Duration 5:04 View on Watch

Fain, a former electrician who made an unexpected ascent to the top role this spring, and his team deployed a pugnacious strategy that hit directly at criticism that the UAW has long been too chummy with carmakers.

“I thought it was important to bring in people that weren’t ingrained in the system,” Fain told The Wall Street Journal in August.

The group includes Chris Brooks, a 39-year-old labor activist recruited early this year to manage the new president’s transition team who then became a top aide. He helped overhaul the 88-year-old union, bringing a renewed militancy and empowering rank-and-file workers by pushing for frequent rallies and events where Fain heard them out.

Part of his strategy has also been to make sure nonunion workers at factories in the South were listening. Fain indicated on Sunday that the union would turn to organizing at automakers such as EV leader Tesla and foreign car companies.

New communications director Jonah Furman, 33, coordinated a publicity campaign to make Fain and coverage of the strike ubiquitous in the media. Fain shared details of the contract talks on weekly livestream updates, a tactic that stunned auto executives accustomed to behind-closed-doors discussions.

New York labor attorney Ben Dictor, 36, was heavily involved in the union’s biggest break from the past: holding talks with the three big automakers simultaneously. For decades, the UAW had picked one company to negotiate a new contract, and then used those terms as a template for the other two automakers. This time, the union combined talks to pit the companies against one another and accelerate deals with all three.

Longtime UAW members also worked closely with the new leader to shape its current strategy. Members must vote to approve the deals in coming weeks.

Adversarial talks

Contract talks with the three Detroit automakers, which happen every four years, are always contentious. But auto executives say these have been the most adversarial they can remember.

“The UAW’s leaders have called us the enemy in these negotiations,” Ford Executive Chair Bill Ford said in an October speech before the agreement with the union was solidified. “I will never consider our employees as enemies.”

He signaled that the union’s demands could hurt the company. “Ford’s ability to invest in the future is not just a talking point. It’s the absolute lifeblood of our company,” he said. “And if we lose it, we will lose to the competition. America loses. Many jobs will be lost.”

Higher labor costs in the past prodded carmakers to open factories in Mexico and elsewhere, part of the reason the UAW’s ranks are down more than 70% from their peak in the 1970s.

In the wake of GM and Chrysler’s government-led restructurings in 2009, priority was put on bringing their labor costs more in line with foreign rivals.

Wall Street and politicians, including President Biden and former President Donald Trump, closely monitored the UAW strike. Also paying attention were executives at foreign automakers in the U.S., who worried that the spillover effect from big contracts in Detroit could put upward pressure on their own wages.

Some company executives questioned whether Fain’s team would rather let a high-profile strike play out than work hard to get a deal.

“It is clear Shawn Fain wants to make history for himself, but it can’t be to the detriment of our represented team members and the industry,” GM Chief Executive Mary Barra said in a statement Sept. 29.

Fain, an Indiana native, emerged from a reform faction of the union for a surprise win in March, the first time in more than 70 years that a challenger defeated a presidential candidate from the UAW’s longtime ruling party. UAW leadership had long been regarded as insular, predictable and guarded, composed of union lifers who rose up from the auto-factory floor and spent years on negotiation teams before taking the lead.

Fain, 55, won after a change in rules let members, instead of chapter officials, vote directly for their leadership. The voting revision came after a corruption scandal that became public in 2017. A sprawling federal investigation led to convictions of more than a dozen UAW officials, and sent two former presidents to prison.

The new president and the reform slate, called Unite All Workers for Democracy, or UAWD, vowed to return the UAW to its powerhouse stature when it set the wages and benefits for the auto industry.

Brooks, a former labor journalist from Tennessee, has been described as the nucleus of Fain’s team. He previously led the contract campaign during the NewsGuild of New York’s two-year battle with the New York Times that ended in May with an at least 10.6% wage increase.

In the past, he had criticized the UAW as overly cooperative with the automakers and too quick to give concessions. In a 2016 op-ed in Dollars & Sense magazine, he lamented the UAW’s “top-down brand of business unionism, which has led to its deeply concessionary approach to collective bargaining and new organizing.”

Brooks was central to Fain’s chaos-inducing strike strategy, in which select facilities at each of the Detroit automakers were taken down with little notice. Fain said the approach, which he escalated during the strike by adding more and more facilities, allowed the union to be nimble and apply pressure at key profit centers that hurt the automakers. It was a change from the all-company walkouts that were previously typical—and had never been tried before by the UAW at all three companies.

Brooks also encouraged pop-up events across the country where Fain met with members and spoke alongside Sanders and union leaders. The rallies were new for many longtime UAW workers.

Often at Brooks’s side was Dictor, who has worked with the NewsGuild and local chapters of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

Dictor, who graduated from the University of Florida and got his law degree in New York, received national attention for being the first attorney to question Trump under oath after he left the White House, in a lawsuit brought by protesters in 2015 who said they were attacked by Trump tower security guards.

As the union’s top attorney on the labor negotiations, he advised about working under an expired contract, a byproduct of the union’s strike strategy that had some workers on strike while others at the same company remained on the job. “You are the union’s eyes and ears in your facility. We are asking you to be on alert for any changes the company may be making now that the contract has expired,” Dictor advised members in a September video.

Furman, who had worked for Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez and was the lead singer and bassist in a Boston indie-rock band named Krill, spearheaded the union’s bare-knuckle social-media strategy, where it updated members on negotiations and frequently posted videos taunting company executives about their pay.

“Jim Farley took in $21 million last year,” said Fain in a livestream, referring to Ford’s chief executive. “We need him to do two things right now: Look in the mirror and look in Ford’s bank account.”

Fain said GM factory workers would have to log years on the job to make what CEO Barra earns in one week. He chided Stellantis Chief Executive Carlos Tavares for the “pathetic irony” of him not showing up at the negotiating table after the executive said the company was struggling with absenteeism.

The executives at times responded with sharply worded written statements and comments in interviews but overall kept a lower profile than Fain.

In September, automakers seized on leaked messages purported to be from Furman’s account on X, formerly Twitter, where he referenced keeping the companies “wounded for months” and damaging their reputations. His remarks incensed company executives and fed their view that union leaders were more interested in spotlighting their ideology than reaching agreements.

Election mandate

For more than 70 years, the UAW had been ruled by one dominant caucus, started by former president Walter Reuther, who in the 1950s and ’60s built the union into one of the nation’s most powerful labor groups.

In the past few decades, though, the UAW has lost membership and influence. Its active membership has fallen to around 400,000 workers, from 1.5 million during the 1970s. The Detroit automakers began losing market share to Toyota and other foreign competitors, and closed dozens of factories and other facilities since the early 2000s.

The union has added members from other sectors, including higher-education and legal services, but hasn’t been able to meaningfully expand its automotive ranks. Organizing campaigns at southern factories owned by foreign automakers such as Volkswagen and Nissan Motor in recent years have failed.

Today, the UAW’s 146,000 automotive members at the Detroit Three account for a fraction of the nation’s more than one million auto-factory jobs.

The recent corruption scandal further eroded the UAW’s standing. Officials were found to have used union funds to pay for private villas, high-end liquor, golf outings and other luxuries.

The reform-minded UAWD caucus grew from a cross-section of sectors the union represents and vowed to root out corruption.

When Fain sought the UAWD’s endorsement, the reformers weren’t sold on him as a change agent. Some were concerned he might be too connected to the establishment way of bargaining.

“We were skeptical,” said Scott Houldieson, who works at Ford’s Chicago Assembly factory and is chair of the reform group’s steering committee. “‘Is this guy a plant?’” he recalled wondering.

Fain convinced committee members he was serious about moving the union past its corruption-scarred past to elevate the voices of rank-and-file workers—who had made concessions in past negotiations as a result of what Fain called weak leadership.

In March, he edged out incumbent Ray Curry by less than 500 votes in a runoff election. Curry had taken over in 2021 after serving as the union’s secretary-treasurer, the No. 2 position. During the campaign, Curry’s team said Fain lacked experience and pointed out that some of his supporters weren’t union members.

All seven candidates for union leadership posts endorsed by the reform caucus won, a sign members were ready for change.

Brooks was top of mind for many leaders within UAWD, some of whom he worked with previously. He had helped workers at Volkswagen’s Chattanooga, Tenn., plant who tried unsuccessfully to unionize in 2014.

Five years later, he covered a UAW organizing drive at the VW factory as a reporter for Labor Notes, an online publication that describes itself as a voice for union activists. He also closely covered the UAW’s corruption scandal for the publication.

At the NewsGuild of New York, Brooks led the union’s contract campaign and had a knack for channeling the sentiment of the rank-and-file workers, said Jon Schleuss, president of the main NewsGuild-CWA union. Brooks works with a regimented intensity—at the NewsGuild he kept detailed online spreadsheets for workers to plan activities, including a rare one-day strike in December of more than 1,100 New York Times journalists and other union members.

Some early members of the Fain team left in part due to concerns Brooks was too inexperienced and was espousing strategies that were too aggressive, people familiar with the matter said.

Other newcomers joined the staff, including a contingent in the legal and communications department who had worked with the Service Employees International Union, a big healthcare union.

The newly assembled group prioritized swift decision-making and responses to the companies, which required cutting through bureaucracy that had impeded previous bargaining rounds, people familiar with the union’s inner workings said. The UAW pumped out pamphlets and videos to communicate with members—key to ensuring buy-in amid a strike that affected workers unevenly.

“What has moved the needle is our willingness to take action, to be flexible, to be aggressive when we have to,” Fain said in an early October livestream to members.

Fain also recruited union longtimers to join his team, including people in research and organizing who were knowledgeable about the group’s history and had relationships with local chapters. They were key to identifying strike targets that would both cause pain to companies and be supported by workers.

Bold opening

The union began contract negotiations this summer with leverage from a tight labor market, inflationary pressures and an especially profitable recent run for the companies. It made clear things were different by opening with demands that included a 40% wage increase over the four-year contract.

The union further stunned the automakers a few weeks later when Fain appeared on a livestream address to outline a detailed list of the union’s demands, a rare public airing of the state of play from the bargaining table.

On another livestream in August, Fain threw Stellantis’ first contract offer in a trash can.

In September, the union made one of its most visible departures from its past practices by walking out on all three companies at once for the first time. Leaders didn’t call a full strike but instead implemented a start-small strategy by hitting select facilities, and expanded walkouts when they perceived little movement at the bargaining table.

On social media, Fain’s team seemed to relish the disarray the pop-up strikes have caused the car companies. One meme posted in advance of a Fain video to declare fresh walkouts used a GIF from the movie “The Hitman’s Bodyguard,” with a well-known line from actor Samuel L. Jackson: “Tick tock motherf—.” Another post referenced reality TV show “The Bachelorette,” saying stay tuned to find out which company would get the rose.

Not all UAW members have liked the tactics, indicating the stances were too extreme or flippant—some union leaders got complaints from workers after Fain wore an “Eat the Rich” shirt on a livestream.

“We want the public to understand our fight, and to side with us,” Fain said in an early October livestream. “It’s not about theatrics. It’s about power.”

Write to Nora Eckert at nora.eckert@wsj.com and Mike Colias at mike.colias@wsj.com

No comments:

Post a Comment