3 November 2023

LONG READ

Exactly 106 years ago, on November 2, 1917, the world witnessed the Balfour Declaration—an iconic, albeit concise, open letter. In this historic document, Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, de facto pledged Palestine to the Jewish people. What ensued was a century-old saga, where the Arab-Israeli conflict commenced as a territorial dispute between two nations vying for a small piece of the British Empire. However, the origins of this conflict delve far deeper, tracing their roots to ancient history and biblical narratives. Amidst this complex tapestry of events, even figures like the Bolsheviks, Joseph Goebbels, and Richard the Lionheart found their place, each playing a role in a conflict that remains unresolved to this very day.

CONTENT

The sacred city

How it all began

The redrawing of the world

Zion calling

The roots of terror

The war of independence

The sacred city

In December 1917, just eleven months before the conclusion of World War I, British forces made their entry into Jerusalem, a city deserted by the Ottomans. Within the city's walls, hunger and desolation reigned, and the soldiers bore the fatigue of a grueling, months-long Palestinian campaign. Although fresh battles loomed on the horizon, news of the capture of this hallowed city resonated in London as one of the most momentous triumphs in the entire war.

Prime Minister Lloyd George bestowed this victory with the title of a “Christmas gift to the British people.” Across the empire, the chimes of church bells reverberated, and newspapers, accustomed to offering mere glimpses of front-line updates, now featured inspiring illustrations. In these depictions, General Edmund Allenby, the commander of British forces in the Middle East, was portrayed receiving a divine blessing from none other than Richard the Lionheart, a medieval king whose life's mission was the conquest of the Holy Land, but who never succeeded in subduing Jerusalem.

The extraordinary significance attached to what might seem like an ordinary military victory can be ascribed to the fact that during the years of World War I, Britain was undergoing a spiritual renaissance. The unprecedented devastation had stirred a collective sense of anticipation about the impending end of the world, prompting people to seek solace in religion, particularly within the Protestant faith, which held official status in the empire. The return of Jerusalem to the dominion of a Christian monarch was embraced by the faithful as a testament to the inevitability of triumph and the righteousness of their cause.

British Artillery during the Battle for Jerusalem, 1917

It seemed that the sacred city, along with all of historical Palestine, would become yet another shining gem in the crown of the British Empire. However, there was a catch: the British had already promised to hand over Palestine to a completely different group of people, who also laid claim to it. What's more, they made this promise twice to different parties.

The first to whom the British agreed to grant the Holy Land was Sherif (ruler) of Mecca, Hussein, in 1916. At that time, Mecca was firmly under the Ottoman Empire's rule, and the Sherif remained subject to the Sultan's authority. However, Hussein held the belief that, as a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, he possessed a far stronger entitlement to governance over the Arab territories than the Turks. In exchange for his assistance in the war against the Ottoman Empire, the British were willing to acknowledge Hussein's sovereignty, as well as that of his dynasty—the Hashemites. This dynasty was named after their legendary founder, Hashim, who was the great-grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad. In a confidential correspondence with the Sherif, the British undertook to formally recognize him as the ruler of all Arab lands “from Egypt to Persia.” This recognition excluded territories that had already been under the dominion of the British Empire or its protectorates before the outbreak of World War I.

In a confidential correspondence with the Sherif, the British undertook to formally recognize him as the ruler of all Arab lands “from Egypt to Persia”

As His Majesty's officials engaged in correspondence with the Sherif of Mecca, striving to ignite an Arab uprising deep within the Ottoman Empire, another group within the British government pondered how to win the support of an increasingly influential community of religious Zionists. The Zionist movement, with its core goal of establishing an independent Jewish state, extended beyond the Jewish community. Notably, it drew fervent interest from a contingent of Christians, particularly those of a literalist Protestant persuasion who adhered to a strict interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. These Christian supporters found resonance in the notion that the Holy Land should be returned to the Jews, as the Bible itself ordained.

How it all began

The Jews had been dispossessed of their homeland at the advent of a new era, subsequent to a series of ill-fated uprisings against the Roman Empire. Since that time, they had been scattered across the globe, Israel had ceased to exist, and had been rechristened Palestine by the Romans. Over the centuries, various kingdoms and empires had taken their turns in ruling the Holy Land. In the 7th century, Arab conquerors arrived, introducing Islam to the region. Subsequently, crusaders attempted to seize control, with limited success. About four centuries prior to World War I, the Ottoman Empire came to hold sway over Palestine. Yet, their dominion, too, had its twilight.

Both European Jews and Christian Zionists regarded the onset of World War I with tempered enthusiasm, perceiving it as yet another episode in the imperial redrawing of boundaries. In London, however, there was a concerted effort to convince the Zionists of the necessity of supporting the British military with financial, intellectual, and human resources. To accomplish this, the Zionists had to be convinced that the war was aligned with their interests, that the empire's triumph would also signify a victory for their faith. It was crucial to instill in both Jews and Christians the belief that the war wasn't a pursuit of territorial gain, but rather a struggle for the future of humanity and the salvation of human souls. Hence, the second promise of ceding Palestine was conceived, this time not to the Arabs but to the Jews.

It was crucial to instill in both Jews and Christians the belief that the war wasn't a pursuit of territorial gain, but rather a struggle for the future of humanity and the salvation of human souls

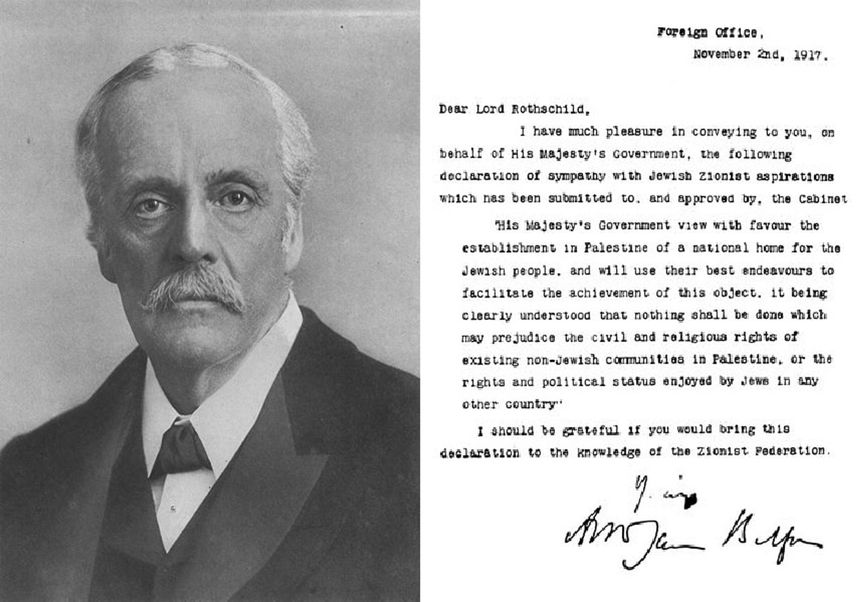

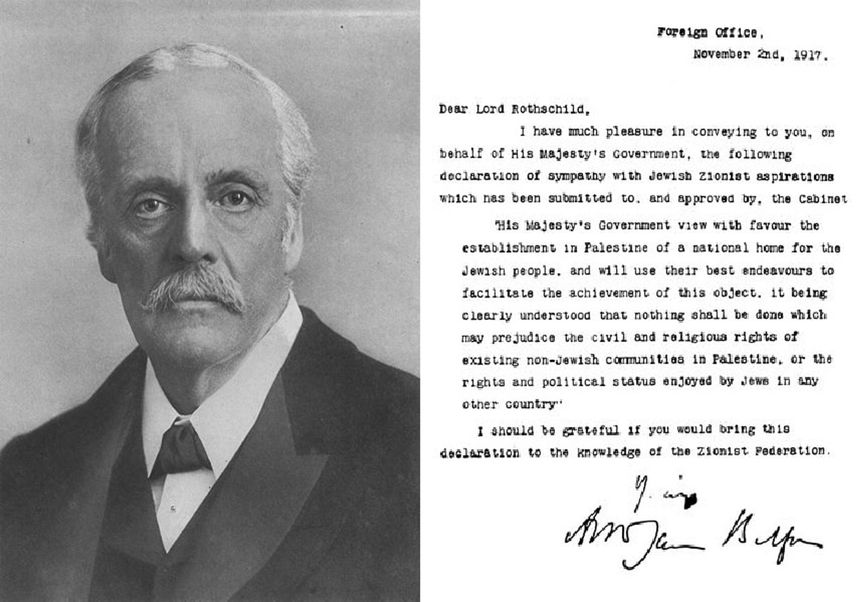

This promise was named the Balfour Declaration, essentially a short open letter addressed to one of the most influential British Jews, Lord Lionel Rothschild. In this letter, Arthur Balfour, who served as the British Foreign Secretary during World War I, conveyed the Empire's understanding of the Zionist movement and its readiness to facilitate the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

Most likely, through such promises, the British aimed not only to align themselves with British Zionists but also to enlist the support of Jews in the Middle East, persuade Americans of the religious legitimacy of their entry into the war, and send a signal to Russian Jews, including members of the new Bolshevik government, about the inopportuneness of withdrawing from the war on the eve of the long-awaited rebirth of the Jewish state.

It is worth acknowledging that World War I could have been won even without the support of Arab tribes and wavering Zionists. The funds allocated by London to the forces led by self-proclaimed Arab King Hussein, totaling more than 11 million pound Sterling (equivalent to roughly a billion dollars in today's prices), enabled them to gain control only over a small and strategically insignificant desert region of the Ottoman Empire. Bolshevik Russia did eventually exit the war, and by the time of the Declaration's publication, the Americans not only entered the war but were already engaged on the European Western Front.

Nonetheless, in 1916 and 1917, victory remained far from certain. In the heart of London, apprehensions loomed that their Muslim subjects might revolt and form an alliance with the Ottoman Sultan, who also bore the mantle of the Caliph, the esteemed religious leader of the Islamic world. The British watched with concern as the United States, typically reticent to abandon its isolationist stance, reluctantly embraced the idea of entering the war. Fearing that the Americans might never commit to the conflict, the British, in turn, found themselves making promises that verged on the unattainable.

“We have given so many conflicting pledges that I do not understand whether we shall ever get out of this chaos without breaking our word,” lamented General Henry Wilson, head of the Imperial General Staff, in 1919, after the war had ended.

The redrawing of the world

Sir Wilson's somber premonitions proved to be true; the British found themselves unable to extricate from the convolution they had created, despite their earnest efforts. For instance, they left Hussein without the promised Near Eastern kingdom on the pretext that he had only been promised Arab lands, and after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, it suddenly became apparent that the Middle East was inhabited not only by Arabs but also by representatives of other nations. Moreover, the originals of the secret correspondence, in which these promises were made, mysteriously disappeared—lost in the archives, destroyed, or perhaps, as some officials insinuated, they never existed, and the cunning Hussein had fabricated the entire story.

As a kind of “consolation prize,” the aging Sherif was granted control over the Hijaz, a territory in the Arabian Peninsula that housed the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina. He had already ruled the Hijaz as the Sherif and later as the self-proclaimed monarch of all Arabs. In 1924, Hussein abdicated the throne in favor of his son Ali, but Ali's reign lasted only a few months. He lost to his competitors from the House of Saud, was stripped of his kingdom, and died in exile. Another of Hussein's sons, Faisal, managed to become the king, first of Syria and then of Iraq, where he founded an unpopular ruling dynasty that came to an end in 1953 along with the overthrow of the first king, Faisal II, the grandson of the initial Faisal. Only Hussein's son Abdullah succeeded in establishing a dynasty that still governs Jordan.

In truth, initially, all these thrones were largely symbolic, as for a long time, real control over the Middle East was exercised by the victors of the First World War, primarily Britain and France.

Formally, the former Ottoman territories were not incorporated into European empires but were assigned to them in the 1920s as so-called “mandate” territories. The precursor to the modern United Nations, the League of Nations, delegated the right to govern the fragments of defeated empires—the mandate—to the victorious states. In the early 20th century, openly racist ideas about African and Asian peoples as incapable of effective self-governance still prevailed in global politics.

It was envisaged that established democracies would assist them in the process of nation-building, maintaining political and economic control over these populations, as well as maintaining military presence in the territories of the new states. League of Nations' mandates were so indefinite and nebulous, and the durations of their applicability so obscure—until such time as these nations were deemed ready to assume responsibility for their own states—that, de facto, they transformed the mandate territories into colonies of European states, although de jure, as already mentioned, they did not incorporate them into their empires.

League of Nations' mandates de facto transformed the mandate territories into colonies of European states

Zion calling

One of the mandate territories that fell into British hands was Palestine. This land was inhabited by local Arabs, both Muslims and Christians, and Jews, of whom very few were born there, but their numbers were growing daily, largely due to London's promise to hand over these lands to create a “national homeland.” Though the term “national homeland” does not equate to the concept of a “sovereign state,” and the Balfour Declaration did not delineate clear boundaries for the future Jewish Palestine, the European and American Jews who flocked to the Middle East aspired to build their state precisely on those lands mentioned in the Bible as belonging to the Israelites.

It didn't take long for conflicts to erupt between the Arabs and the new Jewish arrivals. Foreign Jews seemed strange and dangerous interlopers to the Arabs. They accused them of taking advantage of the post-war devastation and poverty by buying land from impoverished local farmers for a pittance. Furthermore, they were reluctant to employ Arabs, preferring to hire fellow immigrant co-religionists, which exacerbated Arab impoverishment and marginalization.

Jews received substantial support from abroad – religious organizations, including Christian ones, provided funds, lobbied for their interests in Europe and the United States. However, local Arabs had nowhere to turn for assistance. Their kinsmen and co-religionists were divided among several new states, each beset with its own problems, and they lacked the money and international influence to help those living in Palestine. In the late 1920s, anti-Jewish riots erupted in Jerusalem and some other cities where Arabs and Jews lived in close proximity. At that time, it was not yet a full-scale uprising, but rather a series of rather bloody scattered attacks on Jews. However, the onset of a full-fledged Arab revolt was imminent.

The roots of terror

The military wing of the Hamas organization is known as the “Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades.” The most common type of rocket launched by these brigades into Israel is also called the Qassam rocket. Several educational institutions in Gaza bear the name of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, a Syrian preacher who was one of the first to attempt to organize armed resistance against the European powers that divided the Middle East among themselves. After suffering defeat in his native Syria at the hands of the French, who controlled the region under a mandate from the League of Nations, in the early 1930s, he moved to neighboring Palestine and began organizing an armed underground.

His fighters, united under The Black Hand organization, attacked Jewish settlements and British patrols, burned orchards, and detonated administrative buildings, aiming to halt Jewish immigration to Palestine and end the British mandate. In response to the actions of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam's followers, the Jews established their underground fighting organization called the Irgun. Later, alongside other Jewish self-defense units that emerged in the early days of the British mandate, such as Haganah, the Irgun would become the foundation of the armed forces of the independent state of Israel. However, at that time, it was a genuine insurgent group.

Irgun poster calling for settlers to break through to Palestine

Arab and Jewish underground fighters clashed with each other and also opposed the British presence, which both Arabs and Jews viewed as a prolonged occupation.

In a 1935 skirmish with the British, Izz ad-Din al-Qassam was killed, but this didn't halt Arab uprisings; it actually triggered new revolts that eventually evolved into a pan-Arab uprising in Palestine. This uprising spanned from 1936 to 1939 and aimed to halt Jewish immigration and abandon plans to create a Jewish “national homeland” in Palestine. The British managed to suppress the revolt through a combination of force and concessions.

In the midst of military operations and intimidation campaigns, approximately five thousand Arabs lost their lives, and several thousand were imprisoned or forced to flee across the border. This represented the punitive measures faced by Palestinian Arabs. The positive side was the introduction of a series of restrictions on Jews known as the “White Paper.”

Under pressure from protestors, the British agreed to ban the sale of Arab land to Jews and pledged to establish both Arab and Jewish states in Palestine within ten years, by 1949. Additionally, they, for the first time during the mandate, limited Jewish immigration. The number of Jews who had the right to officially settle in Palestine was capped at 25,000 people in 1939 and 20,000 people in the following four years.

The British pledged to establish both Arab and Jewish states in Palestine

The Jews, many of whom had assisted the British in suppressing the Arab revolt, perceived the publication of the White Paper as a betrayal of the commitments made to them in the Balfour Declaration. Moreover, as Europe became increasingly dangerous for Jews due to the rise of the Nazis, the revocation of their legal opportunity to escape such peril was seen as a grave injustice. In retaliation for the White Paper, the Irgun carried out executions of several British officers, but the outbreak of the Second World War temporarily reconciled the empire with Jewish underground groups. Many Irgun and Haganah fighters joined the British or allied forces and fought in Syria and Lebanon against the Vichy French.

In turn, influential Arab families placed their bets on the Germans as the main adversaries of the British. The Nazis, long before the war, portrayed themselves in their propaganda aimed at the Middle East as natural allies of the Arabs in the fight against “Jewish-British imperialism.” The German racial laws did not apply to Arabs, and the Bureau of Anti-Semitic Actions (Antisemitische Aktion) in Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda was renamed the Bureau of Anti-Jewish Actions (Antijüdische Aktion) to avoid angering Arab allies, who also belonged to Semitic peoples.

All of these actions shared similar objectives with the promises the British made to the Sharif of Mecca during World War I: to foment unrest and, ideally, provoke a full-scale uprising behind enemy lines. However, the German efforts proved to be even less effective. Even the most pro-German Arabs were unwilling to confront the still-powerful British Empire. There was no Arab uprising in the British rear. Nonetheless, a Jewish uprising did occur.

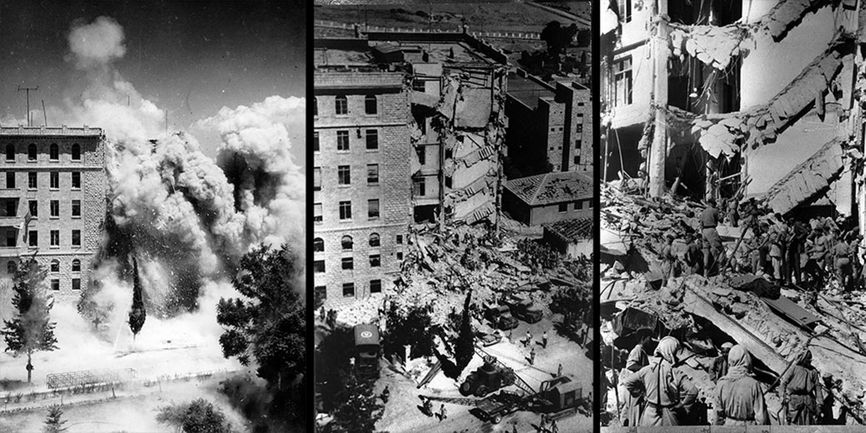

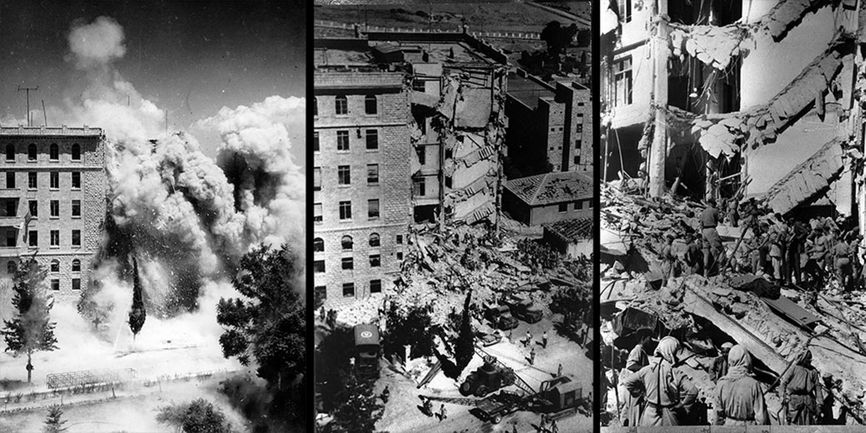

In 1944, Jewish underground fighters resumed their war against the British. This occurred after the true scale of the Holocaust in Europe became apparent, and after London, already aware of the fate of Jews in Nazi-occupied territories, had failed to abandon the White Paper. The Irgun did not hesitate to use terrorist tactics, with the climax being the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where British administrative offices were located. The attack resulted in 91 deaths.

The bombing of the King David on July 22, 1946

Simultaneously with the escalating military pressure, diplomatic efforts gained momentum. In 1945, U.S. President Harry Truman openly proclaimed his moral obligation to safeguard the Jewish people, who had endured significant suffering during World War II. This was a clear indication that the outdated mandate system needed to be brought to a close. Furthermore, within Britain itself, a growing number of people were questioning the necessity of maintaining distant overseas territories that were becoming increasingly complex and precarious.

The contours of the collapse of the once-mighty empire were already taking shape, with the Middle East serving as the most prominent stage for these developments. Before London departed from the Holy Land, in keeping with their promise, they formulated several plans for its division between Jews and Arabs. One of these proposals even suggested the relocation of all Palestinian Arabs to Jordan, which was also under British administration as per the League of Nations mandate.

One of the British proposals even suggested the relocation of all Palestinian Arabs to Jordan

None of these plans gained immediate support from either Arabs or Jews. Therefore, London deemed it best to transfer the task of planning the division of Palestine to the successor of the League of Nations – the United Nations. In 1947, the organization presented its plan, which allotted approximately 55% of the territory of the mandate Palestine to the Jewish state and 45% to the Arab state. Jerusalem was designated to come under the governance of an international administration accountable to the UN. The Arabs once again opposed this proposal.

Their representatives insisted that there was no need for the creation of a Jewish state, as the Jews who had immigrated to Palestine had their homelands – the countries from which they had emigrated – and they should return to them. The Arabs even threatened war against the Jews, which did not earn them sympathy, considering that World War II had ended not too long ago, and memories of the Holocaust were still fresh. Nevertheless, the war did eventually commence.

The war of independence

The path to this war unfolded gradually. In September 1947, the British administration made it known that they intended to withdraw from Palestine, leaving the fate of its inhabitants in their own hands. Just two months later, the United Nations endorsed a plan to partition the Holy Land into Arab and Jewish states. Following this decision, armed confrontations erupted in various regions of Palestine, as Arabs and Jews vied for control of cities, villages, and even individual farms. The British seldom intervened in these clashes, as they were hurriedly preparing for their departure, a task that had to be completed by May 14, 1948—a date chosen by London as the conclusion of their mandate.

As the final British ships with their soldiers remained anchored in the ports of Palestinian cities, awaiting the order to sail away, the Jewish population declared the establishment of their state—the rebirth of Israel. In response, the Arab neighbors of this newly formed state dispatched their troops to Palestine. Arab leaders believed that this intervention would be swift and victorious. They expected the armies of Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon to simply take over from the departing British, prevent the formation of a Jewish state, disarm the Israelis, and transfer authority to local Arabs.

An Israeli officer raises the national flag for the first time on June 8, 1948

But everything didn't go as the Arab kings and generals had anticipated. Their armies fought without coordinating their actions, planning was practically absent, and supplying the troops became difficult because insufficient reserves of weapons, fuel, and provisions had been made by the command. Even the advantage of Arab armies in heavy equipment quickly evaporated. Jewish organizations in Europe and the United States managed to organize the purchase and delivery of artillery, armored vehicles, and even aircraft for the newly established Jewish state from Czechoslovakia, Italy, France, and several other countries.

The conflict drew to a close in July 1949 as Arab armies, one after the other, withdrew from Palestine, hampered by resource shortages and a waning desire to continue hostilities. Israel not only emerged victorious but as an unequivocal triumphant force. It extended its control over nearly 80% of the former Mandatory Palestine territory, including a portion of Jerusalem where international administration never came to fruition.

Israel not only emerged victorious but as an unequivocal triumphant force

What was a victory for the Israelis turned into a catastrophe for their Arab neighbors. This is officially referred to as “Nakba” in Arabic, signifying the war and its aftermath for Palestinians. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were forced to leave their homes. Some did so out of fear of perishing in the crossfire, while others were driven by concerns of retribution from the Israelis for assisting Arab armies. However, many were expelled by Israeli forces. The new state's army was not willing to leave disloyal people in their rear and resorted to forced relocations.

Jews also faced expulsion from their homes, but not in Israel; it was the Jews living in Arab countries who experienced this. Following their defeat by Israel in the Middle East, a wave of anti-Jewish violence and discriminatory laws spread across these Arab lands. There were cases of beatings and lynchings. This ultimately led to a mass exodus of Jews from Arab countries to Israel. They brought with them bitter memories of displacement, which they passed down to their children and grandchildren.

Palestinians also harbor bitter memories. Many of them have lived in refugee camps for generations and cannot forgive the Israelis for taking away their homes. These memories, this inherited distrust passed down from generation to generation, make it impossible for the two peoples to reconcile once and for all. Too many Palestinians are not ready to accept that the Jews will permanently remain on the land they claim as their own. And too many Israelis are unwilling to give those Palestinians who haven't accepted the status quo the opportunity to establish their own state, where anti-Jewish sentiments will always find popularity and support.

Exactly 106 years ago, on November 2, 1917, the world witnessed the Balfour Declaration—an iconic, albeit concise, open letter. In this historic document, Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, de facto pledged Palestine to the Jewish people. What ensued was a century-old saga, where the Arab-Israeli conflict commenced as a territorial dispute between two nations vying for a small piece of the British Empire. However, the origins of this conflict delve far deeper, tracing their roots to ancient history and biblical narratives. Amidst this complex tapestry of events, even figures like the Bolsheviks, Joseph Goebbels, and Richard the Lionheart found their place, each playing a role in a conflict that remains unresolved to this very day.

CONTENT

The sacred city

How it all began

The redrawing of the world

Zion calling

The roots of terror

The war of independence

The sacred city

In December 1917, just eleven months before the conclusion of World War I, British forces made their entry into Jerusalem, a city deserted by the Ottomans. Within the city's walls, hunger and desolation reigned, and the soldiers bore the fatigue of a grueling, months-long Palestinian campaign. Although fresh battles loomed on the horizon, news of the capture of this hallowed city resonated in London as one of the most momentous triumphs in the entire war.

Prime Minister Lloyd George bestowed this victory with the title of a “Christmas gift to the British people.” Across the empire, the chimes of church bells reverberated, and newspapers, accustomed to offering mere glimpses of front-line updates, now featured inspiring illustrations. In these depictions, General Edmund Allenby, the commander of British forces in the Middle East, was portrayed receiving a divine blessing from none other than Richard the Lionheart, a medieval king whose life's mission was the conquest of the Holy Land, but who never succeeded in subduing Jerusalem.

The extraordinary significance attached to what might seem like an ordinary military victory can be ascribed to the fact that during the years of World War I, Britain was undergoing a spiritual renaissance. The unprecedented devastation had stirred a collective sense of anticipation about the impending end of the world, prompting people to seek solace in religion, particularly within the Protestant faith, which held official status in the empire. The return of Jerusalem to the dominion of a Christian monarch was embraced by the faithful as a testament to the inevitability of triumph and the righteousness of their cause.

British Artillery during the Battle for Jerusalem, 1917

It seemed that the sacred city, along with all of historical Palestine, would become yet another shining gem in the crown of the British Empire. However, there was a catch: the British had already promised to hand over Palestine to a completely different group of people, who also laid claim to it. What's more, they made this promise twice to different parties.

The first to whom the British agreed to grant the Holy Land was Sherif (ruler) of Mecca, Hussein, in 1916. At that time, Mecca was firmly under the Ottoman Empire's rule, and the Sherif remained subject to the Sultan's authority. However, Hussein held the belief that, as a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, he possessed a far stronger entitlement to governance over the Arab territories than the Turks. In exchange for his assistance in the war against the Ottoman Empire, the British were willing to acknowledge Hussein's sovereignty, as well as that of his dynasty—the Hashemites. This dynasty was named after their legendary founder, Hashim, who was the great-grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad. In a confidential correspondence with the Sherif, the British undertook to formally recognize him as the ruler of all Arab lands “from Egypt to Persia.” This recognition excluded territories that had already been under the dominion of the British Empire or its protectorates before the outbreak of World War I.

In a confidential correspondence with the Sherif, the British undertook to formally recognize him as the ruler of all Arab lands “from Egypt to Persia”

As His Majesty's officials engaged in correspondence with the Sherif of Mecca, striving to ignite an Arab uprising deep within the Ottoman Empire, another group within the British government pondered how to win the support of an increasingly influential community of religious Zionists. The Zionist movement, with its core goal of establishing an independent Jewish state, extended beyond the Jewish community. Notably, it drew fervent interest from a contingent of Christians, particularly those of a literalist Protestant persuasion who adhered to a strict interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. These Christian supporters found resonance in the notion that the Holy Land should be returned to the Jews, as the Bible itself ordained.

How it all began

The Jews had been dispossessed of their homeland at the advent of a new era, subsequent to a series of ill-fated uprisings against the Roman Empire. Since that time, they had been scattered across the globe, Israel had ceased to exist, and had been rechristened Palestine by the Romans. Over the centuries, various kingdoms and empires had taken their turns in ruling the Holy Land. In the 7th century, Arab conquerors arrived, introducing Islam to the region. Subsequently, crusaders attempted to seize control, with limited success. About four centuries prior to World War I, the Ottoman Empire came to hold sway over Palestine. Yet, their dominion, too, had its twilight.

Both European Jews and Christian Zionists regarded the onset of World War I with tempered enthusiasm, perceiving it as yet another episode in the imperial redrawing of boundaries. In London, however, there was a concerted effort to convince the Zionists of the necessity of supporting the British military with financial, intellectual, and human resources. To accomplish this, the Zionists had to be convinced that the war was aligned with their interests, that the empire's triumph would also signify a victory for their faith. It was crucial to instill in both Jews and Christians the belief that the war wasn't a pursuit of territorial gain, but rather a struggle for the future of humanity and the salvation of human souls. Hence, the second promise of ceding Palestine was conceived, this time not to the Arabs but to the Jews.

It was crucial to instill in both Jews and Christians the belief that the war wasn't a pursuit of territorial gain, but rather a struggle for the future of humanity and the salvation of human souls

This promise was named the Balfour Declaration, essentially a short open letter addressed to one of the most influential British Jews, Lord Lionel Rothschild. In this letter, Arthur Balfour, who served as the British Foreign Secretary during World War I, conveyed the Empire's understanding of the Zionist movement and its readiness to facilitate the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

Most likely, through such promises, the British aimed not only to align themselves with British Zionists but also to enlist the support of Jews in the Middle East, persuade Americans of the religious legitimacy of their entry into the war, and send a signal to Russian Jews, including members of the new Bolshevik government, about the inopportuneness of withdrawing from the war on the eve of the long-awaited rebirth of the Jewish state.

It is worth acknowledging that World War I could have been won even without the support of Arab tribes and wavering Zionists. The funds allocated by London to the forces led by self-proclaimed Arab King Hussein, totaling more than 11 million pound Sterling (equivalent to roughly a billion dollars in today's prices), enabled them to gain control only over a small and strategically insignificant desert region of the Ottoman Empire. Bolshevik Russia did eventually exit the war, and by the time of the Declaration's publication, the Americans not only entered the war but were already engaged on the European Western Front.

Nonetheless, in 1916 and 1917, victory remained far from certain. In the heart of London, apprehensions loomed that their Muslim subjects might revolt and form an alliance with the Ottoman Sultan, who also bore the mantle of the Caliph, the esteemed religious leader of the Islamic world. The British watched with concern as the United States, typically reticent to abandon its isolationist stance, reluctantly embraced the idea of entering the war. Fearing that the Americans might never commit to the conflict, the British, in turn, found themselves making promises that verged on the unattainable.

“We have given so many conflicting pledges that I do not understand whether we shall ever get out of this chaos without breaking our word,” lamented General Henry Wilson, head of the Imperial General Staff, in 1919, after the war had ended.

The redrawing of the world

Sir Wilson's somber premonitions proved to be true; the British found themselves unable to extricate from the convolution they had created, despite their earnest efforts. For instance, they left Hussein without the promised Near Eastern kingdom on the pretext that he had only been promised Arab lands, and after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, it suddenly became apparent that the Middle East was inhabited not only by Arabs but also by representatives of other nations. Moreover, the originals of the secret correspondence, in which these promises were made, mysteriously disappeared—lost in the archives, destroyed, or perhaps, as some officials insinuated, they never existed, and the cunning Hussein had fabricated the entire story.

As a kind of “consolation prize,” the aging Sherif was granted control over the Hijaz, a territory in the Arabian Peninsula that housed the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina. He had already ruled the Hijaz as the Sherif and later as the self-proclaimed monarch of all Arabs. In 1924, Hussein abdicated the throne in favor of his son Ali, but Ali's reign lasted only a few months. He lost to his competitors from the House of Saud, was stripped of his kingdom, and died in exile. Another of Hussein's sons, Faisal, managed to become the king, first of Syria and then of Iraq, where he founded an unpopular ruling dynasty that came to an end in 1953 along with the overthrow of the first king, Faisal II, the grandson of the initial Faisal. Only Hussein's son Abdullah succeeded in establishing a dynasty that still governs Jordan.

In truth, initially, all these thrones were largely symbolic, as for a long time, real control over the Middle East was exercised by the victors of the First World War, primarily Britain and France.

Formally, the former Ottoman territories were not incorporated into European empires but were assigned to them in the 1920s as so-called “mandate” territories. The precursor to the modern United Nations, the League of Nations, delegated the right to govern the fragments of defeated empires—the mandate—to the victorious states. In the early 20th century, openly racist ideas about African and Asian peoples as incapable of effective self-governance still prevailed in global politics.

It was envisaged that established democracies would assist them in the process of nation-building, maintaining political and economic control over these populations, as well as maintaining military presence in the territories of the new states. League of Nations' mandates were so indefinite and nebulous, and the durations of their applicability so obscure—until such time as these nations were deemed ready to assume responsibility for their own states—that, de facto, they transformed the mandate territories into colonies of European states, although de jure, as already mentioned, they did not incorporate them into their empires.

League of Nations' mandates de facto transformed the mandate territories into colonies of European states

Zion calling

One of the mandate territories that fell into British hands was Palestine. This land was inhabited by local Arabs, both Muslims and Christians, and Jews, of whom very few were born there, but their numbers were growing daily, largely due to London's promise to hand over these lands to create a “national homeland.” Though the term “national homeland” does not equate to the concept of a “sovereign state,” and the Balfour Declaration did not delineate clear boundaries for the future Jewish Palestine, the European and American Jews who flocked to the Middle East aspired to build their state precisely on those lands mentioned in the Bible as belonging to the Israelites.

It didn't take long for conflicts to erupt between the Arabs and the new Jewish arrivals. Foreign Jews seemed strange and dangerous interlopers to the Arabs. They accused them of taking advantage of the post-war devastation and poverty by buying land from impoverished local farmers for a pittance. Furthermore, they were reluctant to employ Arabs, preferring to hire fellow immigrant co-religionists, which exacerbated Arab impoverishment and marginalization.

Jews received substantial support from abroad – religious organizations, including Christian ones, provided funds, lobbied for their interests in Europe and the United States. However, local Arabs had nowhere to turn for assistance. Their kinsmen and co-religionists were divided among several new states, each beset with its own problems, and they lacked the money and international influence to help those living in Palestine. In the late 1920s, anti-Jewish riots erupted in Jerusalem and some other cities where Arabs and Jews lived in close proximity. At that time, it was not yet a full-scale uprising, but rather a series of rather bloody scattered attacks on Jews. However, the onset of a full-fledged Arab revolt was imminent.

The roots of terror

The military wing of the Hamas organization is known as the “Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades.” The most common type of rocket launched by these brigades into Israel is also called the Qassam rocket. Several educational institutions in Gaza bear the name of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, a Syrian preacher who was one of the first to attempt to organize armed resistance against the European powers that divided the Middle East among themselves. After suffering defeat in his native Syria at the hands of the French, who controlled the region under a mandate from the League of Nations, in the early 1930s, he moved to neighboring Palestine and began organizing an armed underground.

His fighters, united under The Black Hand organization, attacked Jewish settlements and British patrols, burned orchards, and detonated administrative buildings, aiming to halt Jewish immigration to Palestine and end the British mandate. In response to the actions of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam's followers, the Jews established their underground fighting organization called the Irgun. Later, alongside other Jewish self-defense units that emerged in the early days of the British mandate, such as Haganah, the Irgun would become the foundation of the armed forces of the independent state of Israel. However, at that time, it was a genuine insurgent group.

Irgun poster calling for settlers to break through to Palestine

Arab and Jewish underground fighters clashed with each other and also opposed the British presence, which both Arabs and Jews viewed as a prolonged occupation.

In a 1935 skirmish with the British, Izz ad-Din al-Qassam was killed, but this didn't halt Arab uprisings; it actually triggered new revolts that eventually evolved into a pan-Arab uprising in Palestine. This uprising spanned from 1936 to 1939 and aimed to halt Jewish immigration and abandon plans to create a Jewish “national homeland” in Palestine. The British managed to suppress the revolt through a combination of force and concessions.

In the midst of military operations and intimidation campaigns, approximately five thousand Arabs lost their lives, and several thousand were imprisoned or forced to flee across the border. This represented the punitive measures faced by Palestinian Arabs. The positive side was the introduction of a series of restrictions on Jews known as the “White Paper.”

Under pressure from protestors, the British agreed to ban the sale of Arab land to Jews and pledged to establish both Arab and Jewish states in Palestine within ten years, by 1949. Additionally, they, for the first time during the mandate, limited Jewish immigration. The number of Jews who had the right to officially settle in Palestine was capped at 25,000 people in 1939 and 20,000 people in the following four years.

The British pledged to establish both Arab and Jewish states in Palestine

The Jews, many of whom had assisted the British in suppressing the Arab revolt, perceived the publication of the White Paper as a betrayal of the commitments made to them in the Balfour Declaration. Moreover, as Europe became increasingly dangerous for Jews due to the rise of the Nazis, the revocation of their legal opportunity to escape such peril was seen as a grave injustice. In retaliation for the White Paper, the Irgun carried out executions of several British officers, but the outbreak of the Second World War temporarily reconciled the empire with Jewish underground groups. Many Irgun and Haganah fighters joined the British or allied forces and fought in Syria and Lebanon against the Vichy French.

In turn, influential Arab families placed their bets on the Germans as the main adversaries of the British. The Nazis, long before the war, portrayed themselves in their propaganda aimed at the Middle East as natural allies of the Arabs in the fight against “Jewish-British imperialism.” The German racial laws did not apply to Arabs, and the Bureau of Anti-Semitic Actions (Antisemitische Aktion) in Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda was renamed the Bureau of Anti-Jewish Actions (Antijüdische Aktion) to avoid angering Arab allies, who also belonged to Semitic peoples.

All of these actions shared similar objectives with the promises the British made to the Sharif of Mecca during World War I: to foment unrest and, ideally, provoke a full-scale uprising behind enemy lines. However, the German efforts proved to be even less effective. Even the most pro-German Arabs were unwilling to confront the still-powerful British Empire. There was no Arab uprising in the British rear. Nonetheless, a Jewish uprising did occur.

In 1944, Jewish underground fighters resumed their war against the British. This occurred after the true scale of the Holocaust in Europe became apparent, and after London, already aware of the fate of Jews in Nazi-occupied territories, had failed to abandon the White Paper. The Irgun did not hesitate to use terrorist tactics, with the climax being the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where British administrative offices were located. The attack resulted in 91 deaths.

The bombing of the King David on July 22, 1946

Simultaneously with the escalating military pressure, diplomatic efforts gained momentum. In 1945, U.S. President Harry Truman openly proclaimed his moral obligation to safeguard the Jewish people, who had endured significant suffering during World War II. This was a clear indication that the outdated mandate system needed to be brought to a close. Furthermore, within Britain itself, a growing number of people were questioning the necessity of maintaining distant overseas territories that were becoming increasingly complex and precarious.

The contours of the collapse of the once-mighty empire were already taking shape, with the Middle East serving as the most prominent stage for these developments. Before London departed from the Holy Land, in keeping with their promise, they formulated several plans for its division between Jews and Arabs. One of these proposals even suggested the relocation of all Palestinian Arabs to Jordan, which was also under British administration as per the League of Nations mandate.

One of the British proposals even suggested the relocation of all Palestinian Arabs to Jordan

None of these plans gained immediate support from either Arabs or Jews. Therefore, London deemed it best to transfer the task of planning the division of Palestine to the successor of the League of Nations – the United Nations. In 1947, the organization presented its plan, which allotted approximately 55% of the territory of the mandate Palestine to the Jewish state and 45% to the Arab state. Jerusalem was designated to come under the governance of an international administration accountable to the UN. The Arabs once again opposed this proposal.

Their representatives insisted that there was no need for the creation of a Jewish state, as the Jews who had immigrated to Palestine had their homelands – the countries from which they had emigrated – and they should return to them. The Arabs even threatened war against the Jews, which did not earn them sympathy, considering that World War II had ended not too long ago, and memories of the Holocaust were still fresh. Nevertheless, the war did eventually commence.

The war of independence

The path to this war unfolded gradually. In September 1947, the British administration made it known that they intended to withdraw from Palestine, leaving the fate of its inhabitants in their own hands. Just two months later, the United Nations endorsed a plan to partition the Holy Land into Arab and Jewish states. Following this decision, armed confrontations erupted in various regions of Palestine, as Arabs and Jews vied for control of cities, villages, and even individual farms. The British seldom intervened in these clashes, as they were hurriedly preparing for their departure, a task that had to be completed by May 14, 1948—a date chosen by London as the conclusion of their mandate.

As the final British ships with their soldiers remained anchored in the ports of Palestinian cities, awaiting the order to sail away, the Jewish population declared the establishment of their state—the rebirth of Israel. In response, the Arab neighbors of this newly formed state dispatched their troops to Palestine. Arab leaders believed that this intervention would be swift and victorious. They expected the armies of Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon to simply take over from the departing British, prevent the formation of a Jewish state, disarm the Israelis, and transfer authority to local Arabs.

An Israeli officer raises the national flag for the first time on June 8, 1948

But everything didn't go as the Arab kings and generals had anticipated. Their armies fought without coordinating their actions, planning was practically absent, and supplying the troops became difficult because insufficient reserves of weapons, fuel, and provisions had been made by the command. Even the advantage of Arab armies in heavy equipment quickly evaporated. Jewish organizations in Europe and the United States managed to organize the purchase and delivery of artillery, armored vehicles, and even aircraft for the newly established Jewish state from Czechoslovakia, Italy, France, and several other countries.

The conflict drew to a close in July 1949 as Arab armies, one after the other, withdrew from Palestine, hampered by resource shortages and a waning desire to continue hostilities. Israel not only emerged victorious but as an unequivocal triumphant force. It extended its control over nearly 80% of the former Mandatory Palestine territory, including a portion of Jerusalem where international administration never came to fruition.

Israel not only emerged victorious but as an unequivocal triumphant force

What was a victory for the Israelis turned into a catastrophe for their Arab neighbors. This is officially referred to as “Nakba” in Arabic, signifying the war and its aftermath for Palestinians. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were forced to leave their homes. Some did so out of fear of perishing in the crossfire, while others were driven by concerns of retribution from the Israelis for assisting Arab armies. However, many were expelled by Israeli forces. The new state's army was not willing to leave disloyal people in their rear and resorted to forced relocations.

Jews also faced expulsion from their homes, but not in Israel; it was the Jews living in Arab countries who experienced this. Following their defeat by Israel in the Middle East, a wave of anti-Jewish violence and discriminatory laws spread across these Arab lands. There were cases of beatings and lynchings. This ultimately led to a mass exodus of Jews from Arab countries to Israel. They brought with them bitter memories of displacement, which they passed down to their children and grandchildren.

Palestinians also harbor bitter memories. Many of them have lived in refugee camps for generations and cannot forgive the Israelis for taking away their homes. These memories, this inherited distrust passed down from generation to generation, make it impossible for the two peoples to reconcile once and for all. Too many Palestinians are not ready to accept that the Jews will permanently remain on the land they claim as their own. And too many Israelis are unwilling to give those Palestinians who haven't accepted the status quo the opportunity to establish their own state, where anti-Jewish sentiments will always find popularity and support.

No comments:

Post a Comment