Ruth Scurr

Wed, 22 November 2023

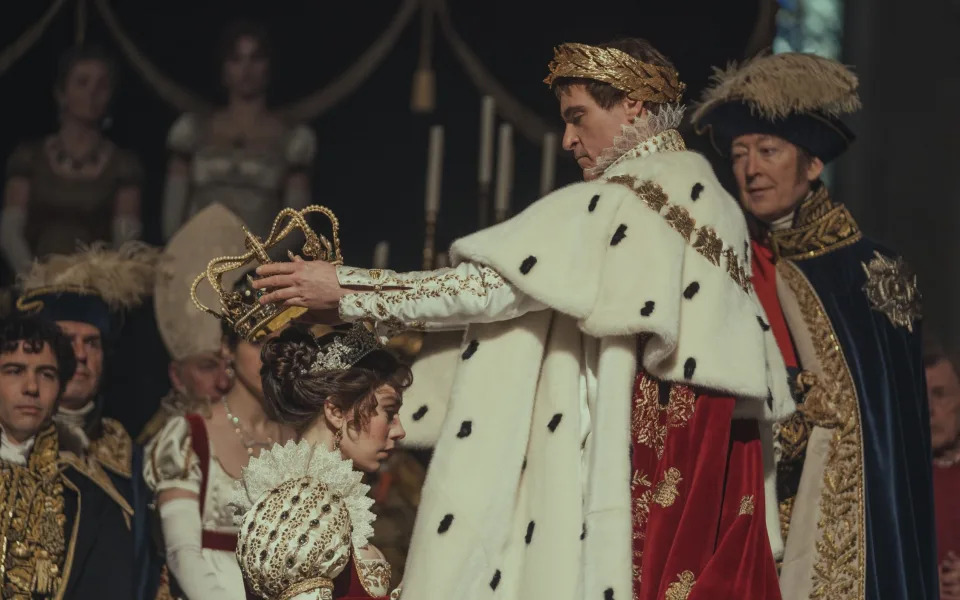

Joaquin Phoenix and Vanessa Kirby in Ridley Scott's Napoleon - Aidan Monaghan

“Everything concerned with the late Emperor Napoleon belongs to British history”, claimed the catalogue entry for Napoleon’s carriage when it was exhibited at Madame Tussaud and Sons in 1843. The carriage had been sent to London as a war trophy soon after the Battle of Waterloo and, after being displayed at Mr Bullock’s museum of natural curiosities in Piccadilly, it toured the country, on the orders of the Prince Regent, so more members of the public could enjoy climbing into it and sitting where Napoleon had sat before the Duke of Wellington defeated him.

The carriage was a mobile office, bedroom, dressing room, kitchen and dining room, fitted out with telescopes, an atlas and an inkwell. Hundreds and thousands of British citizens wanted to be close to the objects that had been close to Napoleon – even his travelling coffee pot seemed part of British history. There was a huge outpouring of anglophone newspapers, books and artworks about him during his career, exile and after his death.

Ridley Scott’s new film about Napoleon revives this long-standing British obsession with the Corsican soldier. “He came from nothing. He conquered everything”, the trailer asserts, though neither of these statements is strictly true. The film opens with a gruesomely glamourized version of the execution of Marie Antoinette, showing the French Revolution at its absolute worst: a mob of cabbage-and-tomato-throwing French citizens bray as their deposed and defiant queen’s head is cut off. Napoleon, magnificently played by Joaquin Phoenix, stands close to the guillotine, an unknown soldier in 1793, glowering with disapproval. The point here is not that Napoleon witnessed the death of Marie Antoinette (he did not) but that he disapproved of the chaos unleashed by the French Revolution (he did, but he owed his entire career to it).

Napoleon’s relationship to the French Revolution is too deep and complex a matter for any film. Abel Gance’s five-and-a-half-hour silent epic from 1927 is the closest anyone has ever, perhaps will ever, come to evoking Napoleon’s rise through the trauma of the Revolution on screen. Scott is more concerned with Napoleon’s relationship with Great Britain.

The Siege of Toulon in 1793, at which Napoleon, a scruffy artillery officer, still known as Bonaparte, first displayed his genius for military strategy, is thrillingly recreated. An English soldier shouts “sh-t bag” at the future emperor as he masterminds the destruction of the beautiful English tall ships in the harbour of Toulon. Sweating, frightened, wounded, courageous: Napoleon from this point on is in a personal conflict with Britain. Later he loses his temper with the English ambassador and yells, “You think you are so great because you have boats”. Two centuries on, the idea that the British got on Napoleon’s nerves is still funny.

The Siege of Toulon in 1793, at which Napoleon first displayed his genius for military strategy - Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images

There has always been fear and awe behind British jokes at Napoleon’s expense, as though Britain needed to create a suitably impressive antagonist. Napoleon inherited the wars of the French Revolution and by 1802 Britain was France’s only unvanquished enemy. After the brief Peace of Amiens, when Britain finally recognised the French Republic, war between the two countries broke out again. English children grew up terrified that Napoleon the bogeyman of nursery rhymes might eat them: “just as pussy tears a mouse”.

Popular prints and cartoons equating Napoleon with the devil tried to deflect into ridicule the very real fear that he might be about to invade. Firmly in the English tradition of thinking about Napoleon, Scott’s film portrays him as a warmonger who is by turns sinister, comic and ultimately unknowable.

Napoleon’s decision to crown himself Emperor of the French held a mirror up to Britain’s monarchy. Loyalist, anti-reform journals and pamphlets asserted affection for George III mixed with anxiety about the state of the nation. The Rival Gardeners, a print from 1803, showed Bonaparte and George III in their gardens on either side of the Channel, each growing a crown in a tub hooped with gold. Bonaparte’s weedy crown wilts on its stem, while George III’s thrives at the top of an oak sapling. “The Heart of Oak will flourish to the end of the World”, reads the hubristic caption. Meanwhile, radical, pro-reform commentators and statesmen such as the Whig Charles James Fox, celebrated Napoleon whilst still thinking him an upstart, intoxicated with his own success.

The Plumb-pudding in danger: William Pitt the Younger, British Prime Minister, left, and Napoleon I of France carve up the globe which 'is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetites' - Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Scott’s take on Napoleon’s coronation is brilliant. Although he had gone to enormous lengths to bring the Pope to Paris for the ceremony, on the day itself, 2 December 1804, Napoleon placed the crown on his own head, then crowned his wife Josephine. Scott shows Napoleon awkwardly balancing the crown on top of the gold laurel wreath he is already wearing, all very precarious and rapid, the crown no sooner on his head than off again. Vanessa Kirby as Josephine, kneels meekly before her husband to receive her crown, exuding a sexy aura of ambitious submission. Coronations, the ultimate set-pieces of monarchical constitutions, were gloriously sent-up by Napoleon: “I found the crown of France lying in the gutter. I picked it up and put it on my head.”

Sex is another long-standing British preoccupation projected onto Napoleon. Josephine was six years older than him, she had lost the father of her two children to the guillotine before they met and was lucky to have survived herself. No sooner were they married than they both had affairs, Napoleon whilst conducting a brutal invasion of Egypt, Josephine with another soldier in Paris. British satirists leapt immediately onto the idea Napoleon was a sexually inadequate cuckold.

A James Gillray cartoon, published soon after the coronation, looked back on the early days of Napoleon’s infatuation with Josephine, showing him peeking at her from behind a curtain as she dances naked before one of her previous lovers, who is twice his size. Over 200 years of smirking at the phrase “Not tonight Josephine”, listed in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations as originating in the early 19th century, is transcended by the compelling sexual chemistry between Scott’s Napoleon and Josephine. Their love story is the counterpoint to the film’s panoramic battle scenes.

In one controversial scene, which raised concerns about glorifying domestic violence before the film was released, Napoleon slaps Josephine as they are signing their divorce papers. For different reasons, both are conflicted about what they are doing: Josephine because she doesn’t want to lose her status, Napoleon because he still loves her but needs a wife who can give him a son. “Do it for your country!” Napoleon demands as he hits Josephine whose pen is faltering.

This vehement and contorted interpretation of patriotism – the idea that a self-made, self-crowned emperor must produce a legitimate male heir to secure the future stability of the state – is more British than French. Napoleon’s second wife, Marie-Louise of Austria, was Marie-Antoinette’s great-niece. Their son, known as the King of Rome, was born in 1811. A George Cruikshank cartoon from three years later shows Napoleon teaching his son to swear “eternal enmity to those islanders the English… swear by the flames of hell… swear to shovel their accursed country into the sea.”

Scott is right to lash out at historians who try to diminish his artistic achievement by pointing out factual inaccuracies. Imagination has always had a part to play in trying to understand a life as gigantic as Napoleon’s. “We must leave him to posterity” the British poet and novelist Helena Maria Williams wrote in 1815, “Time will place his figure in the point of view, and at the proper distance, to become a study for mankind.” One of the very best books about him is Simon Ley’s novel The Death of Napoleon, which ends with the softly spoken line: “Napoleon, you are my Napoleon.” The Napoleon in Scott’s film is his own: the result of a creative collaboration between himself and Phoenix. More British than French, but no less fascinating for that.

Napoleon's Ridley Scott on critics and cinema 'bum ache'

18th November 2023

Scott announced he was making Napoleon on the day he wrapped his previous film, The Last Duel, which starred Jodie Comer.

She was originally cast as his Josephine, but had to pull out after the dates were pushed back by the pandemic.

With Napoleon heading into cinemas, Scott is about to restart filming Gladiator 2, with Paul Mescal and Denzel Washington, a shoot interrupted by the actors' strike.

So why go back to Gladiator? "Why not, are you kidding?"

He also has another movie in the pipeline which is already written and cast, but what it is, "I'm not going to tell you."

And he will celebrate his 86th birthday later this month.

Many might be happy to slow down, but not Scott. He will make films for the rest of his days, he tells me.

"I go from here to Malta, I shoot in Malta, finish there and I've already recce'd what I'm doing next."

So would he have any advice for his younger self?

"No advice. I did pretty good. I got there," comes his characteristically direct reply.

18th November 2023

BBC

By Katie Razzall

Culture and media editor

Sir Ridley Scott is famously forthright.

The director of celebrated films including Gladiator, Alien, Thelma & Louise and Blade Runner certainly speaks his mind.

Does he seek out advice? Asking someone what they think is a "disaster", he tells me.

What about his lack of a best director Oscar - despite being at the helm of some of the most memorable films of the past four decades?

"I don't really care."

And as for the historians who have suggested his latest movie, Napoleon, is factually inaccurate: "You really want me to answer that?... it will have a bleep in it."

We meet in a plush hotel in central London.

Scott had recently arrived from Paris, where the movie - which stars Joaquin Phoenix as the French soldier turned emperor, and Vanessa Kirby as his wife (and obsession) Josephine - had its world premiere.

It's a visual spectacle that contrasts the intimacy of the couple's relationship with the actions of a man whose lust for power brought about the deaths of an estimated three million soldiers and civilians.

"He's so fascinating. Revered, hated, loved… more famous than any man or leader or politician in history. How could you not want to go there?"

The film is two hours and 38 minutes long. Scott says if a movie is longer than three hours, you get the "bum ache factor" around two hours in, which is something he constantly watches for when he's editing.

"When you start to go 'oh my God' and then you say 'Christ, we can't eat for another hour', it's too long."

In spite of the "bum ache" issue, it's been reported that he plans a longer, final director's cut for Apple TV+ when the movie hits the streamer, but "we're not allowed to talk about that".

Napoleon has been well reviewed in many parts of the UK media. Five stars in the Guardian for "an outrageously enjoyable cavalry charge of a movie". Four stars in The Times for this "spectacular historical epic" and in Empire for "Scott's entertaining and plausible interpretation of Napoleon".

The French critics have been less positive.

Le Figaro said the film could be renamed "Barbie and Ken under the Empire". French GQ said there was something "deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny" in seeing French soldiers in 1793 shouting "Vive La France" with American accents.

And a biographer of Napoleon, Patrice Gueniffey in Le Point magazine, attacked the film as a "very anti-French and very pro-British" rewrite of history.

"The French don't even like themselves" Scott retorts. "The audience that I showed it to in Paris, they loved it."

In his movie, Napoleon's empire-building land grabs are distilled into six vast battle scenes.

One of the emperor's greatest victories, at Austerlitz in 1805, sees the Russian army lured onto an icy lake (shot at "an airfield just outside London") before the cannons are turned on them.

"The reverse angle in the trees was where I made Gladiator… I managed to blend them digitally so you get the scale and the scope".

As the cannonballs hurtle into the ice, bloodied soldiers and horses are sucked into the freezing waters, desperately trying to escape.

It's dramatic. It's terrifying. It is also beautiful.

"I'm blessed with a good eye, that's my strongest asset," says South Shields-born Sir Ridley, who went to art school first in Hartlepool and then London.

In the 1970s he was one of the UK's most renowned commercial directors, making, he tells me, two adverts a week in his heyday.

He always wanted to direct films but "I was too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone", and "I didn't know how to get in."

Once he did, he rose fast.

Scott's visual artistry makes him a consummate creator of worlds, whether that's outer space in Alien and The Martian, civil war Somalia in Black Hawk Down, medieval England in Robin Hood or the Roman Empire in Gladiator.

An accomplished artist, he does his own storyboarding.

"You could publish them as comic strips," he says. "A lot of people can't translate what's on paper to what it's going to be and that's my job."

His Napoleon, Joaquin Phoenix, tells me Scott also "draws pictures, as he's coming to work, of what the scene is."

He finds Scott an open and receptive director. "He's figured everything out and yet he's also able to spontaneously pivot" when new ideas are suggested, on this occasion even when there were 500 extras, a huge crew and multiple cannons.

Phoenix was "excited" to work with Scott again, 23 years after he was cast as the emperor Commodus in Gladiator.

"The studio did not want me for Gladiator. In fact, Ridley was given an ultimatum and he fought for me and it was just this extraordinary experience."

Scott has called Phoenix "probably the most special, thoughtful actor" he has ever worked with.

The leading actors had freedom to develop the relationship between Napoleon and Josephine, a woman six years older than him, who he divorced because she was unable to provide him with an heir, but whose name was on his lips when he died in exile on St Helena. "France, the Army, the Head of the Army, Josephine" were the Emperor's last words.

Vanessa Kirby says of her experience being directed by Scott that "none of it was prescriptive from the start and I thought that was really freeing."

But she adds that she had to adjust to the pace at which he works.

"He moves really fast. You might have five big scenes in one day, which means you're on the fly."

They shot Napoleon in just 61 days. "If you know anything about movies, that should have been 120," Scott tells me.

In the early days, he used to operate the camera on his films as well as direct - think The Duellists, Alien, Thelma & Louise, though it wasn't allowed on Blade Runner.

He says he realised where the real power lay - with the camera operator and the first AD - and didn't want to relinquish it.

On Napoleon he worked with up to 11 cameras at the same time and directed them from an air conditioned trailer, saying: "It's 180 degrees outside and I'm sitting inside shouting 'faster!'."

Using all those cameras shooting from different angles "frees the actor to come off-piste and improvise" because you don't need to repeat endless takes (which is "disastrous").

Immortalising Napoleon on film was something Scott's hero Stanley Kubrick tried and failed to do. "He couldn't get it going, surprisingly, because I thought he could get anything going." That was down to money, says Scott.

His Napoleon watches Marie Antoinette die at the guillotine and fires a cannonball at the Sphinx. The artistic licence in this impressionistic film has put up the backs of some historians.

Scott says 10,400 books have been written about Napoleon, "that's one every week since he died."

His question, he tells me, to the critics who say the film isn't historically accurate is: "Were you there? Oh you weren't there. Then how do you know?"

The director of celebrated films including Gladiator, Alien, Thelma & Louise and Blade Runner certainly speaks his mind.

Does he seek out advice? Asking someone what they think is a "disaster", he tells me.

What about his lack of a best director Oscar - despite being at the helm of some of the most memorable films of the past four decades?

"I don't really care."

And as for the historians who have suggested his latest movie, Napoleon, is factually inaccurate: "You really want me to answer that?... it will have a bleep in it."

We meet in a plush hotel in central London.

Scott had recently arrived from Paris, where the movie - which stars Joaquin Phoenix as the French soldier turned emperor, and Vanessa Kirby as his wife (and obsession) Josephine - had its world premiere.

It's a visual spectacle that contrasts the intimacy of the couple's relationship with the actions of a man whose lust for power brought about the deaths of an estimated three million soldiers and civilians.

"He's so fascinating. Revered, hated, loved… more famous than any man or leader or politician in history. How could you not want to go there?"

The film is two hours and 38 minutes long. Scott says if a movie is longer than three hours, you get the "bum ache factor" around two hours in, which is something he constantly watches for when he's editing.

"When you start to go 'oh my God' and then you say 'Christ, we can't eat for another hour', it's too long."

In spite of the "bum ache" issue, it's been reported that he plans a longer, final director's cut for Apple TV+ when the movie hits the streamer, but "we're not allowed to talk about that".

Napoleon has been well reviewed in many parts of the UK media. Five stars in the Guardian for "an outrageously enjoyable cavalry charge of a movie". Four stars in The Times for this "spectacular historical epic" and in Empire for "Scott's entertaining and plausible interpretation of Napoleon".

The French critics have been less positive.

Le Figaro said the film could be renamed "Barbie and Ken under the Empire". French GQ said there was something "deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny" in seeing French soldiers in 1793 shouting "Vive La France" with American accents.

And a biographer of Napoleon, Patrice Gueniffey in Le Point magazine, attacked the film as a "very anti-French and very pro-British" rewrite of history.

"The French don't even like themselves" Scott retorts. "The audience that I showed it to in Paris, they loved it."

In his movie, Napoleon's empire-building land grabs are distilled into six vast battle scenes.

One of the emperor's greatest victories, at Austerlitz in 1805, sees the Russian army lured onto an icy lake (shot at "an airfield just outside London") before the cannons are turned on them.

"The reverse angle in the trees was where I made Gladiator… I managed to blend them digitally so you get the scale and the scope".

As the cannonballs hurtle into the ice, bloodied soldiers and horses are sucked into the freezing waters, desperately trying to escape.

It's dramatic. It's terrifying. It is also beautiful.

"I'm blessed with a good eye, that's my strongest asset," says South Shields-born Sir Ridley, who went to art school first in Hartlepool and then London.

In the 1970s he was one of the UK's most renowned commercial directors, making, he tells me, two adverts a week in his heyday.

He always wanted to direct films but "I was too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone", and "I didn't know how to get in."

Once he did, he rose fast.

Scott's visual artistry makes him a consummate creator of worlds, whether that's outer space in Alien and The Martian, civil war Somalia in Black Hawk Down, medieval England in Robin Hood or the Roman Empire in Gladiator.

An accomplished artist, he does his own storyboarding.

"You could publish them as comic strips," he says. "A lot of people can't translate what's on paper to what it's going to be and that's my job."

His Napoleon, Joaquin Phoenix, tells me Scott also "draws pictures, as he's coming to work, of what the scene is."

He finds Scott an open and receptive director. "He's figured everything out and yet he's also able to spontaneously pivot" when new ideas are suggested, on this occasion even when there were 500 extras, a huge crew and multiple cannons.

Phoenix was "excited" to work with Scott again, 23 years after he was cast as the emperor Commodus in Gladiator.

"The studio did not want me for Gladiator. In fact, Ridley was given an ultimatum and he fought for me and it was just this extraordinary experience."

Scott has called Phoenix "probably the most special, thoughtful actor" he has ever worked with.

The leading actors had freedom to develop the relationship between Napoleon and Josephine, a woman six years older than him, who he divorced because she was unable to provide him with an heir, but whose name was on his lips when he died in exile on St Helena. "France, the Army, the Head of the Army, Josephine" were the Emperor's last words.

Vanessa Kirby says of her experience being directed by Scott that "none of it was prescriptive from the start and I thought that was really freeing."

But she adds that she had to adjust to the pace at which he works.

"He moves really fast. You might have five big scenes in one day, which means you're on the fly."

They shot Napoleon in just 61 days. "If you know anything about movies, that should have been 120," Scott tells me.

In the early days, he used to operate the camera on his films as well as direct - think The Duellists, Alien, Thelma & Louise, though it wasn't allowed on Blade Runner.

He says he realised where the real power lay - with the camera operator and the first AD - and didn't want to relinquish it.

On Napoleon he worked with up to 11 cameras at the same time and directed them from an air conditioned trailer, saying: "It's 180 degrees outside and I'm sitting inside shouting 'faster!'."

Using all those cameras shooting from different angles "frees the actor to come off-piste and improvise" because you don't need to repeat endless takes (which is "disastrous").

Immortalising Napoleon on film was something Scott's hero Stanley Kubrick tried and failed to do. "He couldn't get it going, surprisingly, because I thought he could get anything going." That was down to money, says Scott.

His Napoleon watches Marie Antoinette die at the guillotine and fires a cannonball at the Sphinx. The artistic licence in this impressionistic film has put up the backs of some historians.

Scott says 10,400 books have been written about Napoleon, "that's one every week since he died."

His question, he tells me, to the critics who say the film isn't historically accurate is: "Were you there? Oh you weren't there. Then how do you know?"

Scott announced he was making Napoleon on the day he wrapped his previous film, The Last Duel, which starred Jodie Comer.

She was originally cast as his Josephine, but had to pull out after the dates were pushed back by the pandemic.

With Napoleon heading into cinemas, Scott is about to restart filming Gladiator 2, with Paul Mescal and Denzel Washington, a shoot interrupted by the actors' strike.

So why go back to Gladiator? "Why not, are you kidding?"

He also has another movie in the pipeline which is already written and cast, but what it is, "I'm not going to tell you."

And he will celebrate his 86th birthday later this month.

Many might be happy to slow down, but not Scott. He will make films for the rest of his days, he tells me.

"I go from here to Malta, I shoot in Malta, finish there and I've already recce'd what I'm doing next."

So would he have any advice for his younger self?

"No advice. I did pretty good. I got there," comes his characteristically direct reply.

‘Napoleon’ Director Ridley Scott Tells Historians to ‘Shut the F— Up’

Published 11/19/23

Director Ridley Scott and Joaquin Phoenix behind-the-scenes

of “Napoleon.”Apple TV+

Did Napoleon really fire a cannon at the pyramids in Egypt? Napoleon director Ridley Scott doesn't care.

In a recent interview with The Sunday Times, the 85-year-old filmmaker behind classics like Alien, Blade Runner and Gladiator dismissed critics who quibble with historical inaccuracies in his movies.

"Like all history, it's been reported. Napoleon dies, then, 10 years later, someone writes a book. Then someone takes that book and writes another book and so, 400 years later there's a lot of imagination [in history books]," Scott said. "When I have issues with historians, I ask: 'Excuse me, mate, were you there? No? Well, shut the f--- up then.'"

Napoleon, a historical epic starring Joaquin Phoenix as the famed French leader and Vanessa Kirby as his wife Joséphine, premiered in Paris last week and hits American theaters on Nov. 22.

While the response has mostly been positive, French critics weren't all so kind. Le Figaro brushed the film off as "Barbie and Ken under the empire," GQ France called it "deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny" and biographer Patrice Gueniffey told Le Point it was "very anti-French and pro-British."

Of course, Scott had a retort for that too. "The French don't even like themselves," he told the BBC. "The audience that I showed it to in Paris, they loved it."

Did Napoleon really fire a cannon at the pyramids in Egypt? Napoleon director Ridley Scott doesn't care.

In a recent interview with The Sunday Times, the 85-year-old filmmaker behind classics like Alien, Blade Runner and Gladiator dismissed critics who quibble with historical inaccuracies in his movies.

"Like all history, it's been reported. Napoleon dies, then, 10 years later, someone writes a book. Then someone takes that book and writes another book and so, 400 years later there's a lot of imagination [in history books]," Scott said. "When I have issues with historians, I ask: 'Excuse me, mate, were you there? No? Well, shut the f--- up then.'"

Napoleon, a historical epic starring Joaquin Phoenix as the famed French leader and Vanessa Kirby as his wife Joséphine, premiered in Paris last week and hits American theaters on Nov. 22.

While the response has mostly been positive, French critics weren't all so kind. Le Figaro brushed the film off as "Barbie and Ken under the empire," GQ France called it "deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny" and biographer Patrice Gueniffey told Le Point it was "very anti-French and pro-British."

Of course, Scott had a retort for that too. "The French don't even like themselves," he told the BBC. "The audience that I showed it to in Paris, they loved it."

No comments:

Post a Comment