Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—And Then Got Written Out of History

Howell Raines. Crown, $36 (576p) ISBN 978-0-593-13775-8

SILENT CAVALRY

HOW UNION SOLDIERS FROM ALABAMA HELPED SHERMAN BURN ATLANTA—AND THEN GOT WRITTEN OUT OF HISTORY

A much-needed addition to the demythologizing literature of the Civil War.

Afresh history of an unknown corner of the Civil War.

During the war, many southerners sided with the Union and joined the bluecoat army; whole counties seceded from their parent states and declared themselves to be part of the U.S. The First Alabama Cavalry was formed with men from hilly northern Alabama, and especially the “Free State of Winston.” They fought from the Battle of Shiloh to the end of the war, participating in Sherman’s March to the Sea and the siege of Atlanta and taking heavy losses. According to Pulitzer Prize winner Raines, the former executive editor of the New York Times, its obscurity is by design, a product of the Lost Cause myth. The champions of that myth, whose history Raines carefully traces, took great pains to erase any hint that the Civil War had anything to do with slavery and instead insisted that secession was a reaction to federal overreach. That commonly held revisionist view would have come as news in Winston County, which, not coincidentally, had the fewest enslaved residents in the entire state. “In general,” writes Raines, “these upland southerners shared the attitude of President Andrew Jackson that the Union was too important to be dissolved over slavery, and that no state had a right to withdraw unilaterally.” A network of Southern historians from Reconstruction onward erased such dissenters and their resistance from memory; Raines finds evidence in the very archives of the state, one of the central sites where “Alabama scholars expended thousands of hours in denial.” The book is rich in information and implication, if repetitive and overlong. Still, it’s a hoot to watch Raines dismantle Shelby Foote, “the wily Mississippian,” and shred one Confederate—and now neo-Confederate—lie after another.

A much-needed addition to the demythologizing literature of the Civil War.Pub Date: Dec. 5, 2023

ISBN: 9780593137758

Page Count: 576

Publisher: Crown

Review Posted Online: Sept. 15, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 1, 2023

Alabama Public Radio | By Andrea Tinker

Published December 13, 2023

Pixabay

A new book is uncovering history about Alabama’s involvement in the U.S. Civil War. SILENT CAVALRY: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—and Then Got Written Out of History is a historical detective nonfiction novel that tells the story of how yeoman farmers and former slaves aided the Union General named William Sherman during the U.S. Civil War.

Howell Raines Profile On Audible

Howell Raines, the author and retired executive editor for the New York Times, said he began this story many years ago.

“When I was 18, and a freshman at Birmingham Southern College, I was reading a book called Stars Fell on Alabama, and it told the story of Unionists from Winston County, Alabama, who were killed by federal recruiters for refusing to enlist in the Confederate Army,” he explained. “And in telling that story, the author, Carl Carmer, said they were led by a man called Sheats. So, I began systematically to try to put together a true biography of Chris Sheats.”

Raines said during the research process for Silent Calvary, he uncovered some surprising information.

“I found letters in the archives between Thomas McAdory Owen, the Alabamian, and Professor William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University, who was the most influential Civil War historian in the United States,” he said. “It seems odd that a New Jersey born Ivy League professor would be pro-Confederate, but he was. And so, between the two of them, they managed to point the Southern, or rather, the American Historical Association in a more Confederate direction.”

SILENT CAVALRY: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—and Then Got Written Out of History, out now.

According to Raines, there were 3,000 white Alabamians who voluntarily enlisted in the Union Army because they did not believe in secession. These Alabamians and the others who enlisted in the Union Army were removed from history by Thomas Macedon. He was the director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History during that time. Macedon said in 1901 that the Alabama Archives in Montgomery would collect only the records of Confederate soldiers.

Raines also said, in North Alabama specifically, there were 2,000 white Alabamians and 16 freed slaves who enlisted in what was called the “1st Alabama Calvary Regiment, U.S.A.”

Alabama Union Soldiers also aided General William Sherman. Sherman was a Union Army General and voluntarily enlisted in the United States Army in May 1861. He was a key figure in the Civil War leading the First Battle of Bull Run and ordering his army of 60,000 men to march through the state of Georgia, burning it in the process.

Raines said the 1st Alabama Calvary fighters were praised by Sherman for their work, but also said the regiment did not do anything much differently than other units.

“They didn't do it so much differently as they did it bravely and efficiently,” he explained. “In addition to being good field soldiers and cavalrymen horsemen, they were very expert at donning civilian clothes and slipping behind Union lines,” Raines continued. “Also, many of their relatives back home in Alabama sent them letters that were militarily useful to General Sherman and the Union army… They were used in very dangerous missions. For example, when the two armies were stalled at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, just north of Atlanta.”

Raines said many of the people who were apart of the 1st Alabama Calvary Regiment, were normal, everyday people.

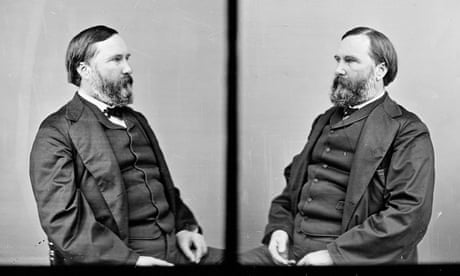

Photo Courtesy Of The Encyclopedia Of Alabama

“Most of them were obscure people. They returned home after the war, often to very hostile reception from neighbors who had been lower the Confederacy, and the Ku Klux Klan set out to punish them,” he explained. “There were hangings. There were burnings. They threatened the life of Chris Sheats, who after the war, went to Huntsville to organize Black voters for grants presidential election. He is falsely depicted in Civil War and Reconstruction [and] the most important history about the war in Alabama, as a coward who was silenced by the Klan. Far from that. he remained outspoken,” Raines continued. “He was so outspoken in service to the Union, President [Ulysses S.] Grant appointed him the U.S. Consult to Denmark. After the war, he then came home and was elected to Congress.”

Raines explained that war is more different from what people might think.

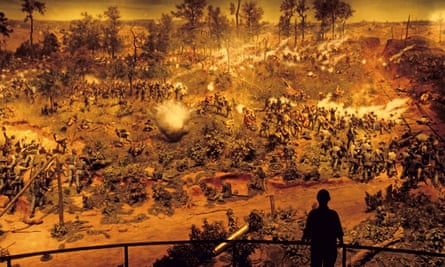

Courtesy Of Britannica

“We tend to think of [war] as big a kind of consistent action, but it actually is very sporadic. There were long days of boring marches, separated by moments of terror. And notably, outside Milledgeville, Georgia, the 1st Alabama Cavalry was sent out on a scouting mission, and they stumbled into a very strong Confederate force. They had a pitch battle,” he explained. “That led to one of the few historic markers that honors the 1st Alabama Cavalry placed there by Georgia officials. There are, so far as I can tell, two historic markers on obscure rural highways in Alabama that take note of the presence and activities of the 1st Alabama Cavalry.”

When the Civil War was finally over, Raines said the perspective of the story was different from other stories in history books.

“The Civil War was unusual in that it was the first conflict in that the losers, that is, the Southern side, got to write the history,” he explained. “The original history of the Civil War, by the first generation … was written from a pro-Confederate point of view. That seems odd by today's standards, but it is a fact that pro-Confederate point of view contributed what was called the myth of The Lost Cause,” Raines said.

Raines’ book SILENT CAVALRY: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta—and Then Got Written Out of History explores more on why the best-known Civil War historians have given no to passing attention to the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment of southerners who chose to fight for the North.

The publication is out now. More details can be found here.

Andrea Tinker is a student intern at Alabama Public Radio. She is majoring in News Media with a minor in African American Studies at The University of Alabama. In her free time, Andrea loves to listen to all types of music, spending time with family, and reading about anything pop culture related.

SHEILA KENNEDY

A jaundiced look at the world we live in.

December 26, 2023

A recent article from the Washington Post challenged my belief in the old adage that history is written by the victors. (It would also appear that Faux News didn’t invent propaganda. Who knew?) Apparently, successfully resisting Reconstruction wasn’t the only tactic employed by pro-slavery Southerners.

They were also able to suppress “inconvenient” history.

As Howell Raines, the author of the essay, noted, “Until a few years ago, I was among the thousands of Southerners who never knew they had kin buried under Union Army headstones.” It appears that a regiment of 2,066 fighters and spies who came from the mountain South were chosen by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman as his personal escort on the March to the Sea. Raines wondered how their history got erased, and found that “the explanation reaches back to Columbia University, whose pro-Confederate Dunning School of Reconstruction History at the start of the 20th century spread a false narrative of Lost Cause heroism and suffering among aristocratic plantation owners.”

As a 10-year-old I stood in the presence of Marie Bankhead Owen, who showed me and my all-White elementary-school classmates the bullet holes in Confederate battle flags carried by “our boys.” She and her husband, Thomas McAdory Owen, reigned from 1901 to 1955 as directors of the archives in a monolithic alabaster building across from the Alabama State Capitol. They made the decision not to collect the service records of an estimated 3,000 White Alabamians who enlisted in the Union Army after it occupied Huntsville, Ala., in 1862. The early loss of this crucial Tennessee River town was a stab to the heart from which the Confederacy never recovered. Neither did the writing of accurate history in Alabama.

The Owens were not alone in what was a national academic movement to play down the sins of enslavers. In the files in Montgomery, I found the century-old correspondence between Thomas Owen and Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning about their mission to give a pro-Southern slant to the American Historical Association.

The essay documents the effort to sanitize the “War Between the States,” by claiming that Southerners had been solidly behind the Confederacy; that the war had been fought about “states’ rights,” not slavery; and–most pernicious of all–that African Americans were “scientifically proven to be a servile race” that brought down Reconstruction because they were incapable of governing.

The fact that few Americans have ever heard of the 1st Alabama Cavalry and the defiant anti-secession activist who led to its founding, Charles Christopher Sheats, documents how such historiographic trickery produced what the Mellon Foundation calls “a woefully incomplete story” of the American past. The foundation’s Monuments Program is spending $500 million to erect accurate memorials to political dissidents, women and minorities who are underrepresented in many best-selling history books.

Recent research has traced the ways in which an “alternate” Southern history became the predominant story of the Civil War.

Dunning was the son of a wealthy New Jersey industrialist who taught him that Southern plantation masters were unfairly punished during Reconstruction. The younger Dunning installed a white-supremacist curriculum at Columbia and, after 1900, started dispatching his doctoral students to set up pro-Confederate history departments at Southern universities. The most influential of these was Walter Lynwood Fleming, whose students at Vanderbilt University produced “I’ll Take My Stand,” a celebration of plantation culture written by 12 brilliant conservative “Agrarian” writers including Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate and Andrew Nelson Lytle…Fleming, who was born on an Alabama plantation, reigned as the director of graduate education at Vanderbilt and peopled Southern history departments with PhDs schooled in the pro-Confederate views he learned from Dunning at Columbia.

It turns out that there were some 100,000 Union volunteers from the South. They were, Howell tells us, “Jacksonian Democrats who hewed to Old Hickory’s 1830 dictum that the Union must be preserved.” Lost Cause historians who had been schooled by Dunning and Fleming glossed over the fact that “White volunteers from the Confederate states made up almost 5 percent of Lincoln’s army.”

Howell concludes by considering how this history was lost.

How then did the Civil War become the only conflict in which, as filmmaker Ken Burns told me, the losers got to write the history, erecting statues of Johnny Reb outside seemingly every courthouse in Alabama? Long story short, after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction, plantation oligarchs regained control of Southern legislatures and state universities started churning out history books that ignored Black people and poor Whites. When national historians set about writing widescreen histories of the war, they relied on these tainted histories.

The essay is lengthy, and filled with fascinating details documenting both accurate history and the dishonest machinations of those whose devotion to Confederate ideology suppressed it.

It made me wonder how often losers have become victors by simply rewriting history…

In his new book, Silent Cavalry, the former New York Times editor tells of loyalties long suppressed in his native Alabama

Martin Pengelly in Washington

@MartinPengelly

“Norman Mailer said every writer has one book that’s a gift from God.” So says Howell Raines, former executive editor of the New York Times, now author of a revelatory book on the civil war, Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers From Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta – And Then Got Written Out of History.

Longstreet: the Confederate general who switched sides on race

“And agnostic as I am, I have to say this was such a gift, one way or another.”

Raines tells the story of the 1st Alabama Cavalry, loyalists who served under Gen William Tecumseh Sherman in campaigns that did much to end the war that ended slavery, only to be scorned by their own state and by historians as the “Lost Cause” myth, of a noble but traduced south, took hold.

For Raines, it is also a family story. As he wrote in the Washington Post, his name is a “version of the biblical middle name of James Hiel Abbott, who … help[ed] his son slip through rebel lines to enlist in the 1st Alabama … That son is buried in the national military cemetery at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Until a few years ago, I was among the thousands of southerners who never knew they had kin buried under Union army headstones.”

The 1st Alabama was organised in 1862 and fought to the end of the war, its duties including forming Sherman’s escort on his famous March to the Sea, its battles including Resaca, Atlanta and Kennesaw Mountain.

To the Guardian, Raines, 80, describes how the 1st Alabama and the “Free State of Winston”, the anti-secession county from which many recruits came, have featured through his life.

“My paternal grandmother gave me my first hint, when I was about five or six, that our family didn’t support the Confederacy. It was a very oblique reference but it stuck in my mind. And then, in 1961, I ran across a reference … in a wonderful book called Stars Fell on Alabama [by Carl Carmer, 1934], and it confirmed … that there were Unionists in my mother’s ancestral county, Winston county, up in the Appalachian foothills.

“So those were the seeds, and I just kept over the years saving string, to use a newspaper term. And I could never rid myself of curiosity about what the real story was. And then when I started reading enough Alabama history to see how these mountain unionists had been libeled in the Alabama history books, that, I suppose, fit my natural curiosity as a contrarian.

“… For years, I thought I would write it as a novel. I had done one novel set in that same county [Whiskey Man, 1977]. And it took me a long time to realise that the true story was better than anything I could make up.”

Raines has written history before: his first book, written in the 1970s when he was a reporter and editor in Georgia and Florida, was My Soul Is Rested, an oral history of the civil rights years. His new book is also inflected with autobiography and follows two memoirs, Fly Fishing Through the Midlife Crisis (1993) and The One That Got Away (2006), the latter published not long after his departure from the Times, in the aftermath of the Jayson Blair affair.

He had, he says, “a very unusual upbringing”, for Alabama in the 1940s and 50s.

“In no house of my extended family was there a single picture of Robert E Lee or any of the Confederate heroes. It didn’t strike me until I was much older that I lived in a different southern world than most other white kids my age in Alabama. Our families not venerating these Confederate icons was the very subtle downstream effect of having had a significant number of unionists and indeed some collateral kin and direct kin who were part of the Union army.

“It’s a curious thing about Alabama. After segregation became such an inflamed issue in the south with the 1954 school desegregation decision [Brown v Board of Education, by the US supreme court], families with unionist heritage quit telling those family stories on the front porch. The only way to find out about it was to dig them out. And it always struck me as the ultimate irony that many of the Klan members in north Alabama in the 1960s, and many of the supporters of George Wallace [the segregationist governor], were actually descendants of Union soldiers without knowing it.”

Reading Stars Fell on Alabama “was a seminal moment. [Carmer’s] observation that Alabama could best be understood as if it was a separate nation within the continental United States: suddenly the quotidian realities that a child accepts as normal or even a young college student accepted as normal, I began to see as odd behavior.

“For example, Alabamians were always complaining in the 1950s and 60s about being looked down upon. And suddenly … I said, ‘Well, there’s a reason for this. If you pick [the infamous Birmingham commissioner of public safety] Bull Connor and George Wallace to be your representatives before the nation on the premier legal and moral issue of the decade” – civil rights – “then they’re going to think you’re strange.”

If Alabamians complained of being looked down upon, many Alabamians looked down on the unionists of Winston county – people too poor to own enslaved workers.

“Even though the story of unionism was suppressed, it survived enough in the political bloodstream of the state that the legislature continued to punish them for 100 plus years after the war. So much so that my cousins in the country went to school in wooden schoolhouses while the schools in the rest of the state were modern, even in the rural counties. And up until I was 10 years old, we had to travel to my grandparents’ farm, only 50 miles from Birmingham, via dirt roads. So this was a matter of punishing through the state budget, this apostasy that sort of otherwise washed out of the civic memory.”

As Raines writes in his introduction to Silent Cavalry, “History is not what happened. It is what gets written down in an imperfect, often underhanded process dominated by self-interested political, economic and cultural authorities.”

He “had to really dig deeply into historiography to understand how this odd thing came to be: that the losers of the civil war got to write the dominant history … [and how] that revisionist view … became nationalised.” That’s what happened in the Lost Cause crusade of the 1870s to 1890s that in turn produced William Archibald Dunning” (1857-1922), a historian at Columbia University in New York who did much to embed the Lost Cause in American culture.”

Raines discusses that process and its later manifestations, not least in relation to The Civil War, Ken Burns’ great 1990 documentary series now subject to revisionist thinking. Burns, his brother Ric and Geoffrey C Ward, a historian who co-wrote the script, are quoted on why the 1st Alabama is absent from their work. But Raines also discusses historians who have begun to tell the stories of the unionist south.

“Histories of the Confederacy were written by Dunning-trained scholars who delivered a warped version of Confederate history: very, very racist [and] very classist, in terms of their contempt for southern poor whites. And those became the fundamental references which national historians … were writing off. A tainted version of southern history.

‘The Lincoln shiver’: a visit to the Soldiers’ Home, a less-known Washington gem

“That obtained until the publication in 1992 of a book called Lincoln’s Loyalists. Richard Nelson Current went back and actually discovered that there were 100,000 citizens of the Confederate states who volunteered in the Union army – almost 5% that came from the south.

“The reviews at the time hailed Current’s book as opening up an entire new field of scholarship. But in fact it was not until about 2000 that a new generation of PhD students, hungry for unexplored topics, began to really dig into this new area of study. And it’s a thriving field now, with a lot of really interesting books.

Asked how his book has been received back home, Raines laughs.

“I don’t know about Alabama. I’m having a signing party in Birmingham in January but that’ll be like-minded southern progressives, for the most part. The defensiveness I referred to … will cause many readers down there to say, ‘Oh, this is just another chance to make Alabama look bad.’

“Alabamians take no responsibility for being on the wrong side of history since 1830, and they think anyone who points that out is is being unfair. So that won’t change.”

Silent Cavalry is published in the US by Crown

By Howell Raines

December 20, 2023

Howell Raines, a former executive editor of the New York Times, is the author of “Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta — and Then Got Written Out of History.”

A new generation of Civil War scholars is filling in what one commentator calls the “skipped history” of White Southerners who fought for the Union Army. For me, the emerging revisionist account of the conflict is personal. I have discovered the story of a great-great-grandfather who was threatened with hanging as a “damned old Lincolnite” by his neighbors in the Alabama mountains.

My given name is an Anglicized version of the biblical middle name of James Hiel Abbott, who died in 1877 after helping his son slip through rebel lines to enlist in the 1st Alabama Cavalry, a distinguished regiment of bluecoat fighters whose story was deliberately excluded from the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery. That son is buried in the national military cemetery at Chattanooga, Tenn. Until a few years ago, I was among the thousands of Southerners who never knew they had kin buried under Union Army headstones.

How did a regiment of 2,066 fighters and spies from the mountain South, chosen by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman as his personal escort on the March to the Sea, get erased? Oddly, the explanation reaches back to Columbia University, whose pro-Confederate Dunning School of Reconstruction history at the start of the 20th century spread a false narrative of Lost Cause heroism and suffering among aristocratic plantation owners.

As a 10-year-old I stood in the presence of Marie Bankhead Owen, who showed me and my all-White elementary-school classmates the bullet holes in Confederate battle flags carried by “our boys.” She and her husband, Thomas McAdory Owen, reigned from 1901 to 1955 as directors of the archives in a monolithic alabaster building across from the Alabama State Capitol. They made the decision not to collect the service records of an estimated 3,000 White Alabamians who enlisted in the Union Army after it occupied Huntsville, Ala., in 1862. The early loss of this crucial Tennessee River town was a stab to the heart from which the Confederacy never recovered. Neither did the writing of accurate history in Alabama.

The Owens were not alone in what was a national academic movement to play down the sins of enslavers. In the files in Montgomery, I found the century-old correspondence between Thomas Owen and Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning about their mission to give a pro-Southern slant to the American Historical Association. They cooperated in Dunning’s plan to hold the first AHA convention in a Southern city, New Orleans. In 1903, Dunning chartered a train to bring Northern professors to Montgomery, where Owen led them on a dramatic nighttime tour of the “Cradle of the Confederacy.” It was a public relations coup for both men, cementing Dunning’s hold on the historical profession and establishing Owen as a national leader in Civil War preservation.

Later, at the 1909 AHA convention in New York, Dunning scored another political triumph by inviting W.E.B. Du Bois to be the first Black PhD holder to address the group, then organizing a scholarly boycott of Du Bois’s challenge to the Dunning School’s white-supremacist theory of Reconstruction, effectively blocking divergent points of view for several decades. All these events contributed to establishing what scholars call the “Myth of the Lost Cause” as a main theme of Civil War scholarship for the first half of the 20th century. The chief tenets of the myth were these: Southerners were solidly behind the Confederacy; the war was about states’ rights, not slavery; African Americans were scientifically proven to be a “servile race”; Reconstruction was a failure because they were incapable of governing.

Dunning died in 1922, but his scheme to put a Confederate spin on Civil War history worked all the way up to the 1960s civil rights movement, when Du Bois’s non-racist theory about the positive accomplishments of Reconstruction gained traction. The fact that few Americans have ever heard of the 1st Alabama Cavalry and the defiant anti-secession activist who led to its founding, Charles Christopher Sheats, documents how such historiographic trickery produced what the Mellon Foundation calls “a woefully incomplete story” of the American past. The foundation’s Monuments Program is spending $500 million to erect accurate memorials to political dissidents, women and minorities who are underrepresented in many best-selling history books.

A place to start could be a statue of Sheats in the Alabama forest where his Free State of Winston speech urged Alabama Unionists to secede from the Confederacy and sparked the surge of enlistments that led to the founding of the 1st Alabama Cavalry. His estimated audience of 2,000 to 3,000 mountain farmers was perhaps the largest antiwar rally held by patriotic Southerners.

As a student, I heard tidbits about Sheats because he was born in 1839 in my mother’s ancestral county, the Free State of Winston. The county was one of 22 in central and northern Alabama that elected anti-Secession delegates to the enslaver-dominated convention that took Alabama out of the Union on Jan. 11, 1861, by the unexpectedly close vote of 61 to 39.

It has taken six decades of historical detective work to rescue an accurate biography of Sheats from the malicious lies in the few Alabama histories that mention him. At 21, he burst from political obscurity to defeat his county’s most powerful plantation owner by a 5-to-1 margin for one of the 100 seats in the Montgomery convention. There the famous secessionist “Fire Eater,” William Lowndes Yancey, threatened to hang Sheats and the bloc of 24 hill-country delegates who refused to sign the Ordinance of Secession to protest their nonslaveholding constituents being forced into a new nation they did not support. Sheats spent much of the war in prison but escaped periodically to begin the clandestine recruitment campaign that led to the founding in 1862 of the 1st Alabama Union Cavalry.

The campaign to erase Sheats and the 1st Alabama from the Civil War narrative was effective enough that I never knew that my great-great-grandfather Abbott ferried farm boys from Walker County, which adjoins Winston, across the Sipsey River so they could sneak north to enlist with Union forces that occupied Huntsville in 1862. Federal archives recount how Abbott kept a canoe on the fast-flowing Sipsey to send potential recruits on their dangerous journeys through the Confederate lines to 1st Alabama enlistment stations in Huntsville and Corinth, Miss. They fled rebel recruitment squads singly or in groups up to 100. So great was the influx that in 1862, Gen. Carlos Buell got Abraham Lincoln’s permission to organize the “Alabama volunteers” into their own regiment.

The fact that their story is missing from the best-known Civil War histories provides dramatic proof of why modern doctoral students are only now establishing a new pantheon of loyal individuals and groups.

The backstory of how Confederate history was written to glorify the defeated side is complicated, and requires a dip into academic historiography and plantation economics. It is also full of odd twists. Dunning was the son of a wealthy New Jersey industrialist who taught him that Southern plantation masters were unfairly punished during Reconstruction. The younger Dunning installed a white-supremacist curriculum at Columbia and, after 1900, started dispatching his doctoral students to set up pro-Confederate history departments at Southern universities. The most influential of these was Walter Lynwood Fleming, whose students at Vanderbilt University produced “I’ll Take My Stand,” a celebration of plantation culture written by 12 brilliant conservative “Agrarian” writers including Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate and Andrew Nelson Lytle.

My research showed that Lytle knew about the Free State of Winston, but chose instead in his popular book “Nathan Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company” to lionize the sociopathic cavalry general who executed an integrated federal force of freed Black slaves and White Unionists as they tried to surrender at Fort Pillow, Tenn., in 1864. Lytle’s mentor, Fleming, who was born on an Alabama plantation, reigned as the director of graduate education at Vanderbilt and peopled Southern history departments with PhDs schooled in the pro-Confederate views he learned from Dunning at Columbia.

The other background factor was King Cotton economics as it developed in the Black Belt lands of the frontier South. After 1830, the best farm acreage was bought up by the wealthy owners of Atlantic seaboard plantations, who brought slavery and their own aristocratic pretensions into new states such as Alabama. Poorer farmers had to settle for small farms in the Appalachian foothills. They could not afford enslaved people, and their Unionism had deep historical roots. The original highland homesteaders revered the “Old Flag” that their forefathers fought for in the Revolution and the War of 1812. Most of the some 100,000 future Union volunteers from the South were Jacksonian Democrats who hewed to Old Hickory’s 1830 dictum that the Union “must be preserved.” Lost Cause historians schooled by Dunning and Fleming simply glossed over the fact that White volunteers from the Confederate states made up almost 5 percent of Lincoln’s army.

The great achievement of Dunning and the Lost Cause historians of his “Dunning School” was to create the impression that the vast majority of White Southerners supported the Confederacy, even though two-thirds of Alabama families did not own enslaved people. White support for the war peaked after the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861 but declined steadily after the Union victory at Shiloh in the spring of 1862. How then did the Civil War become the only conflict in which, as filmmaker Ken Burns told me, the losers got to write the history, erecting statues of Johnny Reb outside seemingly every courthouse in Alabama? Long story short, after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction, plantation oligarchs regained control of Southern legislatures and state universities started churning out history books that ignored Black people and poor Whites. When national historians set about writing widescreen histories of the war, they relied on these tainted histories.

In the case of Alabama, this meant that the two most misleading books on Alabama history were footnoted hundreds of times in scholarly writings. One was Fleming’s pro-Klan “Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama,” published in 1905. Dunning boasted that his star student from Alabama was “none-too reconstructed,” and supervised the dissertation in which Fleming cast Sheats as a coward silenced by Klan threats even though congressional testimony showed that he spoke throughout Alabama urging former enslaved people to vote for Grant. The other book, “Alabama Tories: The 1st Alabama Cavalry, U.S.A., 1862 to 1865,” was published in 1960 as a celebration of the “Confederate Centennial” by William Stanley Hoole, the librarian at the University of Alabama. As chief of the Lost Cause caucus on the Tuscaloosa faculty, Hoole carried on the work of exclusion started by the Owens at the Alabama archives. While they simply sought to bury the 1st Alabama Cavalry, he denigrated it as a lawless band of “hillbilly” war criminals who played no significant military role in the Civil War. In a skimpy sentence, he admitted that the Alabama cavalrymen were selected by Sherman as his personal escort on the March to the Sea, but he ignored official reports of their value to the Union Army.

Those omissions point up another feature of history twisted to fit parochial politics and racial prejudice. For one thing, the 1st Alabama was one of the few integrated units in the Union Army: the regiment of 2,066 recruits included 16 freed enslaved people. The shortchanging of its accomplishments also cast a shadow over important events and colorful characters who deserved attention in mainstream histories. My most surprising discovery was that the 1st Alabama led the Union charge that could have prevented the burning of Atlanta. At Snake Creek Gap in North Georgia on May 9, 1864, they had a chance to rout Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnson’s entire army by charging into its rear. Their attack was called off when one of Sherman’s favorite generals arrived on the scene. In his “Memoirs,” Sherman admitted that his subordinate had cost the Union Army an opportunity that “does not occur twice in a lifetime.”

The 1st Alabama Cavalry’s shining moments came on the march from Chattanooga to Savannah. I never saw an Alabama history that noted the startling fact that the 1st Alabama Cavalry is listed in the “Order of Battle” for the Atlanta campaign. How they came to be picked as the point of the spear that would be driven through the heart of the Confederacy is a story told in the 2020 University of Virginia dissertation of Clayton J. Butler, which was published last year as “True Blue: White Unionists in the Deep South During the Civil War and Reconstruction.” Its author is one of a number of rising historians who have published in the past 25 years the research that enabled me to complete my six-decade quest for the full story of Alabama Unionism.

At the pivotal Battle of Fort McAllister on Dec. 13, 1864, Alabamians were on both sides of the battle lines, as the 1st Alabama faced Confederate neighbors from back home under rebel Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler. Later, the 1st Alabama figured in one of Sherman’s most famous demonstrations of the “hard war” tactics designed to break the will of Confederate soldiers and civilians. Rebel land mines blew off the leg of a 1st Alabama company commander, Lt. Francis Tupper. Sherman rushed to his side and, in a fit of anger, ordered Confederate prisoners of war onto the road, telling them to find the mines by digging them up or stepping on them.

By way of reward for 1st Alabama’s performance on the March to the Sea, Gen. Francis Blair Jr., gave them the place of honor at the right front of Sherman’s 17th Corps in the victory parade through captured Savannah on Dec. 27, 1864. The presence of Alabama soldiers at Savannah and the burning of Atlanta is the kind of belated news that can cause some Civil War buffs to gulp in surprise. Another of the new generation of Civil War students, attorney W. Steven Harrell of Perry, Ga., has found pension records showing that Sheats himself, having been freed from prison, rushed to the front to visit his old friends in the 1st Alabama as Atlanta lay in ashes.

Removing some of the lugubrious monuments beloved by conservative Southerners will allow an appreciation of the internal diversity of a war that claimed about 620,000 American lives. And there’s more to be learned, especially now that the Black Lives Matter movement inspired Alabama Department of Archives and History’s modernizing director, Steven Murray, to correct the mistakes of the Owen legacy. Even he doesn’t know what surprises lurk as cataloguers work through the vast files left by the Owens’ team of Lost Cause manipulators.

Last year, in aiding my research at the archives, my grandson Jasper Raines found the muslin-wrapped rosters of the first three Alabama companies sworn into the Union Army in 1862. For more than 100 years, they lay misfiled in the records of the adjutant general’s office of Alabama’s Confederate government. Murray speculated that the young Thomas McAdory Owen might have gotten them from the Library of Congress director who befriended Owen when he was a post office clerk in D.C. in the 1890s. The question remains, of course, as to whether they were purposely hidden under a false label by Owen himself. Based on what I’ve learned since 1961, when I first ran across Sheats’s name in Alabama folklore, I have to guess yes. When it comes to the history of Alabama’s mountain Unionists, disappearance is the name of the game.

No comments:

Post a Comment