Buenos Aires (AFP) – Argentina's new leader Javier Milei on Wednesday unveiled a series of measures to deregulate the country's struggling economy, eliminating or changing more than 300 rules via presidential decree, including on rent and labor practices.

Issued on: 21/12/2023

Argentine President Javier Milei (C) delivered his speech to the nation from the Casa Rosada presidential palace in Buenos Aires, flanked by his cabinet

© Handout / Argentina's Presidency Press Office/AFP

"The goal is to start along the path to rebuilding the country... and start to undo the huge number of regulations that have held back and prevented economic growth," Milei said in a televised speech from the presidential palace, flanked by his cabinet.

Latin America's third-biggest economy is on its knees after decades of debt and financial mismanagement, with inflation surpassing 160 percent year-on-year and 40 percent of Argentines living in poverty.

Milei, who was elected last month and took office 10 days ago, has pledged to curb inflation, but warned that economic "shock" treatment is the only solution, and that the situation will get worse before it improves.

Among the changes announced on Wednesday are the elimination of a law regulating rent, as well as rules preventing the privatization of state enterprises.

Milei also announced a "modernization of labor law to facilitate the process of creating real jobs" and a series of other deregulatory measures affecting tourism, satellite internet services, pharmaceuticals, wine production and foreign trade.

Following the speech, thousands of people converged on the streets near the Congress to voice their discontent.

The decree was published in the government gazette at midnight. It must now be assessed by a joint committee of lawmakers from both chambers of the legislature within 10 days.

Constitutional law expert Emiliano Vitaliani told AFP that the decree could only be overturned if rejected by both the lower House and the Senate.

"The goal is to start along the path to rebuilding the country... and start to undo the huge number of regulations that have held back and prevented economic growth," Milei said in a televised speech from the presidential palace, flanked by his cabinet.

Latin America's third-biggest economy is on its knees after decades of debt and financial mismanagement, with inflation surpassing 160 percent year-on-year and 40 percent of Argentines living in poverty.

Milei, who was elected last month and took office 10 days ago, has pledged to curb inflation, but warned that economic "shock" treatment is the only solution, and that the situation will get worse before it improves.

Among the changes announced on Wednesday are the elimination of a law regulating rent, as well as rules preventing the privatization of state enterprises.

Milei also announced a "modernization of labor law to facilitate the process of creating real jobs" and a series of other deregulatory measures affecting tourism, satellite internet services, pharmaceuticals, wine production and foreign trade.

Following the speech, thousands of people converged on the streets near the Congress to voice their discontent.

The decree was published in the government gazette at midnight. It must now be assessed by a joint committee of lawmakers from both chambers of the legislature within 10 days.

Constitutional law expert Emiliano Vitaliani told AFP that the decree could only be overturned if rejected by both the lower House and the Senate.

Argentine President Javier Milei has warned of spending cuts equivalent to five percent of gross domestic product in Latin America's third-biggest economy

© Luis ROBAYO / AFP/File

Milei's far-right Libertad Avanza party only has 40 seats in the 257-member lower house and seven senators out of 72. But Milei's margin improves if the members of the center-right Together for Change coalition are taken into account.

'Shock' therapy for economy

For political analyst Lara Goyburu, Milei's moves are not surprising, given how he campaigned for the presidency. But she told AFP that his use of an emergency decree was unusual.

The 53-year-old libertarian and self-described "anarcho-capitalist" has said spending cuts equivalent to five percent of gross domestic product are needed.

Milei's far-right Libertad Avanza party only has 40 seats in the 257-member lower house and seven senators out of 72. But Milei's margin improves if the members of the center-right Together for Change coalition are taken into account.

'Shock' therapy for economy

For political analyst Lara Goyburu, Milei's moves are not surprising, given how he campaigned for the presidency. But she told AFP that his use of an emergency decree was unusual.

The 53-year-old libertarian and self-described "anarcho-capitalist" has said spending cuts equivalent to five percent of gross domestic product are needed.

Labor union members and other Argentines demonstrate in Buenos Aires against the new government of Javier Milei, who has ordered a series of controversial economic reforms

© JUAN MABROMATA / AFP

Before Wednesday's announcement, his administration had already devalued Argentina's peso by more than 50 percent, and announced huge cuts in generous state subsidies of fuel and transport from January.

Milei has also announced a halt to all new public construction projects and a year-long suspension of state advertising.

Last week's measures to tackle inflation were welcomed by the International Monetary Fund, to which Argentina owes $44 billion.

"Over the last century, politicians took pains to expand the power of the state, to the detriment of ordinary Argentines," Milei said Wednesday.

"Our nation, which in the 1920s was the world's top power, has been involved in a series of crises over the last 100 years that all stem from the same cause: budget deficits."

Milei won a resounding election victory in November surfing a wave of fury over decades of recurrent economic crises, marked by debt, rampant money printing, inflation and fiscal deficit.

Argentines remain haunted by hyperinflation of up to 3,000 percent in 1989-1990 and a dramatic economic implosion in 2001.

Before Milei's speech, thousands of people protested against his government in Buenos Aires, waving banners and chanting slogans near the Casa Rosada presidential palace.

Before Wednesday's announcement, his administration had already devalued Argentina's peso by more than 50 percent, and announced huge cuts in generous state subsidies of fuel and transport from January.

Milei has also announced a halt to all new public construction projects and a year-long suspension of state advertising.

Last week's measures to tackle inflation were welcomed by the International Monetary Fund, to which Argentina owes $44 billion.

"Over the last century, politicians took pains to expand the power of the state, to the detriment of ordinary Argentines," Milei said Wednesday.

"Our nation, which in the 1920s was the world's top power, has been involved in a series of crises over the last 100 years that all stem from the same cause: budget deficits."

Milei won a resounding election victory in November surfing a wave of fury over decades of recurrent economic crises, marked by debt, rampant money printing, inflation and fiscal deficit.

Argentines remain haunted by hyperinflation of up to 3,000 percent in 1989-1990 and a dramatic economic implosion in 2001.

Before Milei's speech, thousands of people protested against his government in Buenos Aires, waving banners and chanting slogans near the Casa Rosada presidential palace.

Argentine protesters congregate at Plaza de Mayo Square outside the presidential palace in Buenos Aires as part of the first demonstration against the new government of Javier Milei

© LUIS ROBAYO / AFP

Their route through the city center was lined by military police and other security personnel, including police in full riot gear, in a large show of force that protest organizers criticized as an attempt at provocation.

"This reminds me of the dictatorship" of 1976 to 1983, said Eduardo Belliboni, leader of leftist movement Polo Obrero.

© 2023 AFP

Their route through the city center was lined by military police and other security personnel, including police in full riot gear, in a large show of force that protest organizers criticized as an attempt at provocation.

"This reminds me of the dictatorship" of 1976 to 1983, said Eduardo Belliboni, leader of leftist movement Polo Obrero.

© 2023 AFP

Argentina’s Ruined Railways Will Force Milei to Confront Poverty

Patrick Gillespie

Wed, December 20, 2023

(Bloomberg) -- Patricios, Argentina, looks like a railroad version of the Titanic. Rotting rail ties and shattered glass litter the gutted train warehouse. The town’s economic engine is long abandoned except for the manager’s former office, now a makeshift home for a family of 11. The community doesn’t have a single employer and there’s no sewer, natural gas or paved roads.

Deep in Buenos Aires province, the forgotten town off a muddy road lays bare the root problem facing Javier Milei as he begins his presidency in Argentina vowing to end decades of overspending.

Home to 5,000 residents a few generations back, Patricios cast fewer than 600 votes in the November election. Its decline mirrors that of Argentina itself.

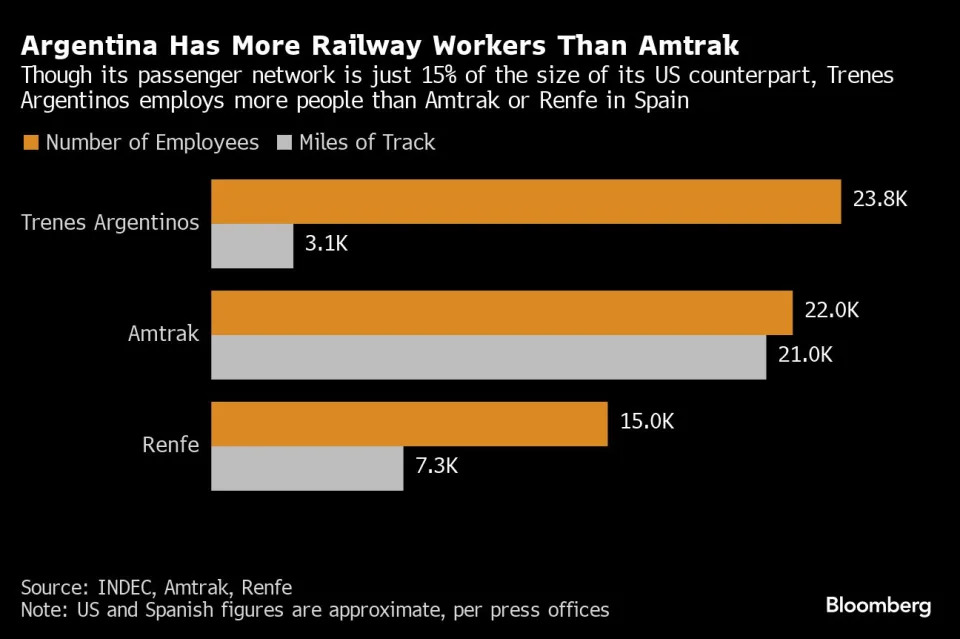

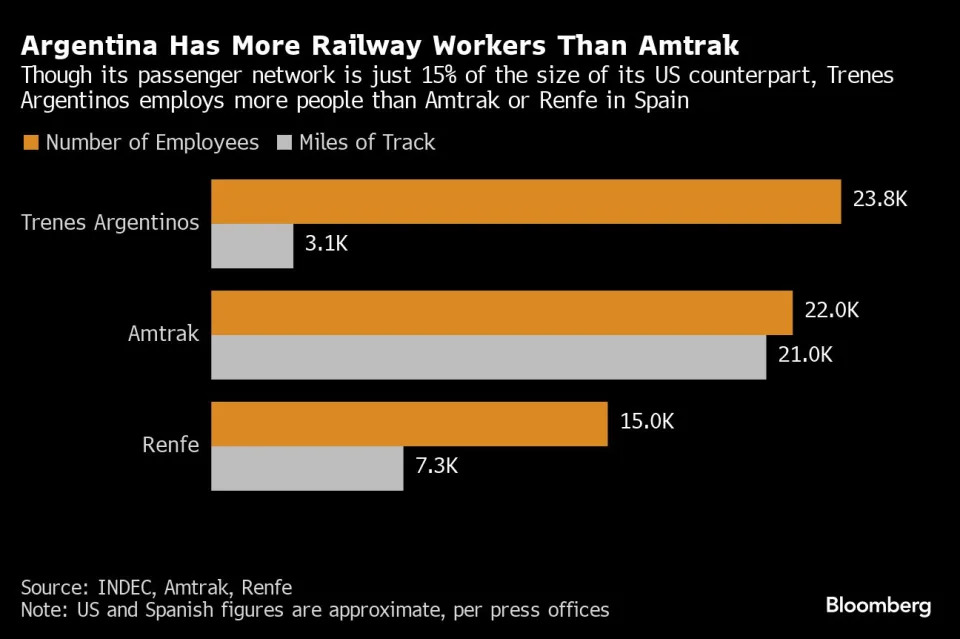

Once Latin America’s best, the nation’s rail system crumbled with its economy over the decades, leaving in its wake hundreds of ghost towns like Patricios. But even though Argentina’s passenger network has shrunk to a little more than 5,000 kilometers (3,105 miles) today from 46,000 kilometers in 1945, state-run Trenes Argentinos employs more people than Amtrak in the US or Spain’s high-speed rail network, Renfe.

Towns like Patricios, where the majority depends on social security or welfare checks, illustrate Milei’s greatest challenge: managing a cratering economy that’s trying to prop up a bloated state. As the president himself warns, taming runaway spending will be painful, so town residents are bracing for the worst.

Argentina “is a train on an open track and there’s no station,” says Carlos Tomas Guiotto, the municipal representative, who calls Patricios a barometer for national trends. “We’ll either find the station or we’ll head out into the fields, fall into a ditch and end in disaster.”

Since 1950, Argentina has spent more time in recession than any other nation except the Democratic Republic of Congo. This year is no different, with the economy lurching into its sixth downturn in a decade.

The country’s $43 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund, its only remaining lifeline, is fraying because the previous government missed deficit targets, spending big before losing the election by a landslide. Trenes Argentinos is a microcosm of the bigger fiscal picture: The state set aside 338 billion pesos in aid for its railway services in this year’s budget, worth $2.2 billion at the time it was approved by congress.

Part of Milei’s chainsaw remedy is to privatize the train service, the biggest public employer, among an alphabet soup of other state-run enterprises. “The only possible solution is austerity — orderly austerity that falls with all its force on the state and not the private sector,” he said after his inauguration. “It's not going to be easy.”

But Argentina’s last attempt at railway privatization failed in the early 1990s as companies abandoned unprofitable lines constructed in the nation’s boom days a century ago. More stations shuttered, and service has improved only glacially in recent years.

The first batch of shock-therapy measures aim to reduce state spending by nearly 3% of gross domestic product. Milei is expected to unveil more detailed plans for belt-tightening and deregulation Wednesday in a midday televised address. And while Wall Street investors are cheering the cuts as long-overdue economic medicine — even if it means higher inflation initially as subsidies, government jobs and welfare are eliminated — those on the ground are increasingly anxious.

Maria Gastaminza breaks down as she describes her fears about Milei, partly fanned by the former government’s misinformation campaign. She’s endured a life of hardship, giving birth at 14 and single parenting most of the years since then. Now 42, Gastaminza inhabits the abandoned railway warehouse in Patricios, converting the old manager’s office and one bathroom into a home for nine of her 10 kids and her current partner, Carlos Rodriguez.

Several of her children receive a state subsidy to cover prescription medicine for celiac disease, thyroid problems and childhood arthritis. And her 12-year-old fears she won’t be able to go to school if Milei privatizes Argentina’s education system — a rumor spread by his opponents, which he denies.

“To be honest, I cried on election day when he won. I was hurting for my kids,” Gastaminza says. “Six of us take daily medications that costs 10,000 pesos for each one, and if I have to pay for everyone’s medication, we can’t keep taking it.”

Milei's spending cuts are coming at a particularly bad time for her town. After years of waiting for a gas pipeline to heat homes and service kitchens, the provincial government put up a billboard announcing it would be installed in a year's time. But Milei’s administration is halting all public works projects that haven't already begun.

Gastaminza, who herself receives a stipend for mothers with several children, says she’s ready to work. But in Patricios “there’s no jobs for women,” so she and the oldest children earn extra income by feeding calves that they sell when they’re ready for grazing. If need be, she says she’s willing to join Rodriguez on farms laying fence for cattle, a low-pay job in which her 14- and 18-year-old sons are already working in the biggest nearby town.

Fiscal austerity, however, spelled doom for Argentine leaders before Milei.

Mauricio Macri opted for gradual cuts during his presidency, which proved fatal for him in the 2019 election. And in 2022, President Alberto Fernandez’s economy minister abruptly resigned less than a year after being blasted by Vice President Cristina Kirchner as too austere. To cover its deficits, the former government printed more than 6 trillion pesos, which resulted in annual inflation that’s galloped past 160%.

Even by Latin American standards, Argentina is an outlier. Public spending is equivalent to 38% of GDP, more than the 35% regional average and well above the 24% seen in the country between 1993 and 2005, according to IMF data. Government jobs like the ones at Argentina’s train service have been the main driver of overspending since the mid 2000s, according to an analysis by economist Milagros Gismondi.

“There isn’t a real consciousness that you have to lower spending in Argentina,” says Gismondi, who was chief of staff at the economy ministry in 2019. “It’s not normal to operate with more train employees than in the United States,” she adds, and unless Argentines understand that’s not sustainable “we’ll continue from one crisis to another.”

Argentina’s state spending spree goes far beyond its railways, though. Governments have added nearly a million jobs to the public payroll since 2012, three times the gains seen in the private sector, labor ministry data show. Welfare has also ballooned. The number of social security recipients who haven’t contributed to the system spiked above 5 million in 2020 from just 172,000 in 2002, according to a report by Andres Schipani at CIAS, a university think tank.

Born out of excess more than a century ago, the train service was nationalized by President Juan Domingo Peron in 1948. The founder of the namesake pro-labor movement that dominated Argentine politics for decades branded the move “economic independence.” But in reality the companies operating the oversized network with a billowing payroll were on the brink of collapse, according to Jorge Waddell, a train historian and author of several books.

Whether democracies or dictatorships, Argentine governments of all stripes have proposed measures that never resolved the train system’s woes. Instead, many overhauls exacerbated spending, crushed service and saw the railway wither from a gluttonous operation to a skeleton of its former self.

Now it’s Milei’s turn and he’ll have to battle the same powerful labor groups that hobbled some of his predecessors. “The unions bring on much more personnel than before — trains today that carry 300 passengers have a staff of 15 or 16 employees,” Waddell said in an interview, noting trains carrying a thousand passengers in the 1980s were staffed by 10 workers or less. “No business can withstand this.”

Unsustainable spending on transit, however, may have already hit a dead end. Milei’s government plans to scrap subsidies in the Buenos Aires area that left the cost of commuter train rides at about 10 cents and subway fares at 6 cents.

Such artificially low prices sometimes provoke chaos. In November, Argentines camped out overnight, queuing for several blocks to buy the few tickets available from the capital to oceanside Mar Del Plata because service is so limited and fares start at less than $3 for the six-hour journey.

Other decisions defy logic. The government restarted service this year between Buenos Aires and the country’s wine capital, Mendoza, after a three-decade hiatus. A train fit for 400 passengers only had 60 people sign up for the grueling 29-hour journey.

In the town of Mechita, Argentina’s government was set to pay $864 million to Russia’s TMH International to build electric trains on a railway that wasn’t electrified. TMH sold its business this year, after global financial sanctions imposed on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine doomed the transaction.

Back in Patricios, Osvaldo Curti is the town’s only remaining railway mechanic. Long retired and widowed, he proudly flaunts the trade certification that led him to work on once-bustling railroads across the country, including the iconic “Train to Heaven” that snakes through the Andes.

The 88-year-old, who lives on his pension and late wife’s social security, worries Argentina is losing something much harder to fix than a budget deficit: a strong work ethic. He sees youth in Patricios opting for welfare checks because they can cobble together other handouts that are either equal to or worth more than the minimum $146 monthly wage.

“You’re better off snoozing belly up,” Curti complains.

He also sees society fraying at his doorstep. Nature is reclaiming the deserted home across from his, and one Saturday in November a drunk refusing to return to a geriatric facility stooped there for hours. Curti called the municipal rep, Guiotto, who couldn’t offer any help beyond talking to the man’s family, who wouldn’t take him back.

“There’s so much abandonment,” Curti says, peering from his front yard. “There’s no future.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Patrick Gillespie

Wed, December 20, 2023

(Bloomberg) -- Patricios, Argentina, looks like a railroad version of the Titanic. Rotting rail ties and shattered glass litter the gutted train warehouse. The town’s economic engine is long abandoned except for the manager’s former office, now a makeshift home for a family of 11. The community doesn’t have a single employer and there’s no sewer, natural gas or paved roads.

Deep in Buenos Aires province, the forgotten town off a muddy road lays bare the root problem facing Javier Milei as he begins his presidency in Argentina vowing to end decades of overspending.

Home to 5,000 residents a few generations back, Patricios cast fewer than 600 votes in the November election. Its decline mirrors that of Argentina itself.

Once Latin America’s best, the nation’s rail system crumbled with its economy over the decades, leaving in its wake hundreds of ghost towns like Patricios. But even though Argentina’s passenger network has shrunk to a little more than 5,000 kilometers (3,105 miles) today from 46,000 kilometers in 1945, state-run Trenes Argentinos employs more people than Amtrak in the US or Spain’s high-speed rail network, Renfe.

Towns like Patricios, where the majority depends on social security or welfare checks, illustrate Milei’s greatest challenge: managing a cratering economy that’s trying to prop up a bloated state. As the president himself warns, taming runaway spending will be painful, so town residents are bracing for the worst.

Argentina “is a train on an open track and there’s no station,” says Carlos Tomas Guiotto, the municipal representative, who calls Patricios a barometer for national trends. “We’ll either find the station or we’ll head out into the fields, fall into a ditch and end in disaster.”

Since 1950, Argentina has spent more time in recession than any other nation except the Democratic Republic of Congo. This year is no different, with the economy lurching into its sixth downturn in a decade.

The country’s $43 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund, its only remaining lifeline, is fraying because the previous government missed deficit targets, spending big before losing the election by a landslide. Trenes Argentinos is a microcosm of the bigger fiscal picture: The state set aside 338 billion pesos in aid for its railway services in this year’s budget, worth $2.2 billion at the time it was approved by congress.

Part of Milei’s chainsaw remedy is to privatize the train service, the biggest public employer, among an alphabet soup of other state-run enterprises. “The only possible solution is austerity — orderly austerity that falls with all its force on the state and not the private sector,” he said after his inauguration. “It's not going to be easy.”

But Argentina’s last attempt at railway privatization failed in the early 1990s as companies abandoned unprofitable lines constructed in the nation’s boom days a century ago. More stations shuttered, and service has improved only glacially in recent years.

The first batch of shock-therapy measures aim to reduce state spending by nearly 3% of gross domestic product. Milei is expected to unveil more detailed plans for belt-tightening and deregulation Wednesday in a midday televised address. And while Wall Street investors are cheering the cuts as long-overdue economic medicine — even if it means higher inflation initially as subsidies, government jobs and welfare are eliminated — those on the ground are increasingly anxious.

Maria Gastaminza breaks down as she describes her fears about Milei, partly fanned by the former government’s misinformation campaign. She’s endured a life of hardship, giving birth at 14 and single parenting most of the years since then. Now 42, Gastaminza inhabits the abandoned railway warehouse in Patricios, converting the old manager’s office and one bathroom into a home for nine of her 10 kids and her current partner, Carlos Rodriguez.

Several of her children receive a state subsidy to cover prescription medicine for celiac disease, thyroid problems and childhood arthritis. And her 12-year-old fears she won’t be able to go to school if Milei privatizes Argentina’s education system — a rumor spread by his opponents, which he denies.

“To be honest, I cried on election day when he won. I was hurting for my kids,” Gastaminza says. “Six of us take daily medications that costs 10,000 pesos for each one, and if I have to pay for everyone’s medication, we can’t keep taking it.”

Milei's spending cuts are coming at a particularly bad time for her town. After years of waiting for a gas pipeline to heat homes and service kitchens, the provincial government put up a billboard announcing it would be installed in a year's time. But Milei’s administration is halting all public works projects that haven't already begun.

Gastaminza, who herself receives a stipend for mothers with several children, says she’s ready to work. But in Patricios “there’s no jobs for women,” so she and the oldest children earn extra income by feeding calves that they sell when they’re ready for grazing. If need be, she says she’s willing to join Rodriguez on farms laying fence for cattle, a low-pay job in which her 14- and 18-year-old sons are already working in the biggest nearby town.

Fiscal austerity, however, spelled doom for Argentine leaders before Milei.

Mauricio Macri opted for gradual cuts during his presidency, which proved fatal for him in the 2019 election. And in 2022, President Alberto Fernandez’s economy minister abruptly resigned less than a year after being blasted by Vice President Cristina Kirchner as too austere. To cover its deficits, the former government printed more than 6 trillion pesos, which resulted in annual inflation that’s galloped past 160%.

Even by Latin American standards, Argentina is an outlier. Public spending is equivalent to 38% of GDP, more than the 35% regional average and well above the 24% seen in the country between 1993 and 2005, according to IMF data. Government jobs like the ones at Argentina’s train service have been the main driver of overspending since the mid 2000s, according to an analysis by economist Milagros Gismondi.

“There isn’t a real consciousness that you have to lower spending in Argentina,” says Gismondi, who was chief of staff at the economy ministry in 2019. “It’s not normal to operate with more train employees than in the United States,” she adds, and unless Argentines understand that’s not sustainable “we’ll continue from one crisis to another.”

Argentina’s state spending spree goes far beyond its railways, though. Governments have added nearly a million jobs to the public payroll since 2012, three times the gains seen in the private sector, labor ministry data show. Welfare has also ballooned. The number of social security recipients who haven’t contributed to the system spiked above 5 million in 2020 from just 172,000 in 2002, according to a report by Andres Schipani at CIAS, a university think tank.

Born out of excess more than a century ago, the train service was nationalized by President Juan Domingo Peron in 1948. The founder of the namesake pro-labor movement that dominated Argentine politics for decades branded the move “economic independence.” But in reality the companies operating the oversized network with a billowing payroll were on the brink of collapse, according to Jorge Waddell, a train historian and author of several books.

Whether democracies or dictatorships, Argentine governments of all stripes have proposed measures that never resolved the train system’s woes. Instead, many overhauls exacerbated spending, crushed service and saw the railway wither from a gluttonous operation to a skeleton of its former self.

Now it’s Milei’s turn and he’ll have to battle the same powerful labor groups that hobbled some of his predecessors. “The unions bring on much more personnel than before — trains today that carry 300 passengers have a staff of 15 or 16 employees,” Waddell said in an interview, noting trains carrying a thousand passengers in the 1980s were staffed by 10 workers or less. “No business can withstand this.”

Unsustainable spending on transit, however, may have already hit a dead end. Milei’s government plans to scrap subsidies in the Buenos Aires area that left the cost of commuter train rides at about 10 cents and subway fares at 6 cents.

Such artificially low prices sometimes provoke chaos. In November, Argentines camped out overnight, queuing for several blocks to buy the few tickets available from the capital to oceanside Mar Del Plata because service is so limited and fares start at less than $3 for the six-hour journey.

Other decisions defy logic. The government restarted service this year between Buenos Aires and the country’s wine capital, Mendoza, after a three-decade hiatus. A train fit for 400 passengers only had 60 people sign up for the grueling 29-hour journey.

In the town of Mechita, Argentina’s government was set to pay $864 million to Russia’s TMH International to build electric trains on a railway that wasn’t electrified. TMH sold its business this year, after global financial sanctions imposed on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine doomed the transaction.

Back in Patricios, Osvaldo Curti is the town’s only remaining railway mechanic. Long retired and widowed, he proudly flaunts the trade certification that led him to work on once-bustling railroads across the country, including the iconic “Train to Heaven” that snakes through the Andes.

The 88-year-old, who lives on his pension and late wife’s social security, worries Argentina is losing something much harder to fix than a budget deficit: a strong work ethic. He sees youth in Patricios opting for welfare checks because they can cobble together other handouts that are either equal to or worth more than the minimum $146 monthly wage.

“You’re better off snoozing belly up,” Curti complains.

He also sees society fraying at his doorstep. Nature is reclaiming the deserted home across from his, and one Saturday in November a drunk refusing to return to a geriatric facility stooped there for hours. Curti called the municipal rep, Guiotto, who couldn’t offer any help beyond talking to the man’s family, who wouldn’t take him back.

“There’s so much abandonment,” Curti says, peering from his front yard. “There’s no future.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

No comments:

Post a Comment