Guy Lodge

Variety

Sun, 31 December 2023

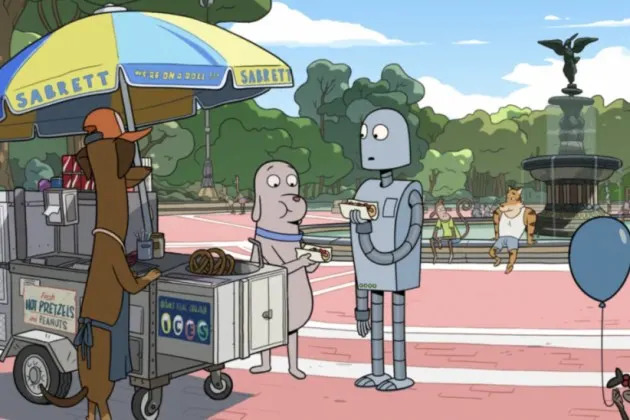

Android or artificial intelligence isn’t the enemy in “Robot Dreams,” Pablo Berger’s gently whimsical fantasy of a loner finding manufactured friendship in a scuzzy vision of 1980s New York City. Indeed, one takeaway from this portrait of a shabby-happy Big Apple populated solely with anthropomorphic animals and surprisingly sensitive automatons is that the world might be a better place without humans in it. Like “Blancanieves,” his silent, flamenco-styled spin on Snow White, Berger’s fourth feature dispenses with dialogue in favor of cheerfully expressive, faux-naive visual storytelling. In all other respects, however, “Robot Dreams” is a significant left turn for the Spanish writer-director, beginning with an entirely fresh medium for him: simple, sharp-lined 2D animation in the manner of a pastel-softened “BoJack Horseman.”

Both the film’s aesthetic and its wordless approach, however, are rooted in American author and illustrator Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel of the same name. Where Varon’s work was primarily targeted at young readers, the audience for Berger’s film — suffused with nostalgia for a Reagan-era New York of roller discos and boomboxes on the sidewalks — is a little harder to pin down. It’s certainly clean enough for kids, with little of the snark or cynicism that drives similarly hip-looking adult animation, though small fry might be perplexed by its drifting, low-incident narrative and overriding air of melancholy. Still, it’s in such odd, in-between niches that cult items can bloom; already well-received at such festivals at Cannes and Annecy, “Robot Dreams” should build a sufficient following to prove its own message to the lonely and forlorn: when it comes to love, quality trumps quantity.

More from Variety

Annecy Prizes: 'Chicken for Linda!,' 'Robot Dreams,' 'Pebble Hill' Take Top Honors

Top Titles from Spain at Cannes 2023

Neon Makes First Cannes Acquisition With Pablo Berger's Animated 'Robot Dreams'

What kind of love, exactly, is the most intriguing question in a tale that hints at a degree of queer companionship between its two seemingly (though not definitively) male-gendered principals, all while remaining wholesomely chaste. (Given they’re a dog and a mechanical robot, it’s hard to imagine how things could be otherwise.) Unnamed protagonist Dog is introduced living a solitary life in the East Village, following a fixed routine of work, walks and glumly microwaved TV dinners — paid no mind by anyone, save the pigeons crowding around his apartment window. He’s a stoic soul, but everyone has a limit: Late one night, inspired by an infomercial on his ever-blaring television set, he orders a flatpack build-your-own-robot-kit, promoted in much the same manner as a set of Ginsu steak knives.

Whatever it costs, it’s worth it. From the moment of assembly, the unnamed Robot improbably turns out to be a most affectionate and responsive compadre, forever fixated on his canine owner with a metallic grin and perma-wide eyes. He’s not much of a conversationalist, but then neither is Dog. Their summer days are spent sightseeing, sunbathing, hotdog-eating, rollerskating through Central Park — generally taking Manhattan in more or less the manner Cole Porter described decades before, though their special song is Earth, Wind and Fire’s “September.” That ever-elastic disco nugget soundtracks multiple buddy montages of varying mood and motion: Its ebullience matches the effervescent early stages of their friendship, only to gradually become an ironic counterpoint in a story of loss and subconscious yearning.

For September comes, and with it, separation: After a day’s gambolling at Coney Island, Robot’s sea-soaked joints swiftly rust, rendering him immobile. Unable to carry his pal home, and with the beach thereafter closed for the winter, Dog must endure the winter alone — all while the abandoned Robot withers and freezes in the cold, his parts plundered by piratical critters. Only in multiple dream sequences (thus part-answering Philip K. Dick’s burning question about androids, though no electric sheep are in evidence) can he attempt a reunion with Dog. Spring will come, as will some manner of closure, though it’s fair to say the uncompromised joys of the film’s opening acts are never regained. Counter to happily-ever-after endings of the Disney variety, “Robot Dreams” embraces the pleasingly mature philosophy that there can be more than one soulmate in an individual’s life, and that a finite relationship isn’t a failed one.

It’s a poignant arc that perhaps isn’t quite robust enough to power a 100-minute feature given to rhythmic and narrative repetition. “Robot Dreams” would have been no less effective or affecting as a short subject, though that format would have admittedly kerbed the gleeful volume of nifty visual gags that Berger packs around his sweet, slender story — many of them wittily attuned to the period (frozen food and advertising trends of the era come in for a good ribbing) and the anything-goes street life of New York itself. Above all else, Berger’s film delights in the kind of eccentric, incidental sights and sounds from which dreams — human, animal or android — can spring.

Sun, 31 December 2023

Android or artificial intelligence isn’t the enemy in “Robot Dreams,” Pablo Berger’s gently whimsical fantasy of a loner finding manufactured friendship in a scuzzy vision of 1980s New York City. Indeed, one takeaway from this portrait of a shabby-happy Big Apple populated solely with anthropomorphic animals and surprisingly sensitive automatons is that the world might be a better place without humans in it. Like “Blancanieves,” his silent, flamenco-styled spin on Snow White, Berger’s fourth feature dispenses with dialogue in favor of cheerfully expressive, faux-naive visual storytelling. In all other respects, however, “Robot Dreams” is a significant left turn for the Spanish writer-director, beginning with an entirely fresh medium for him: simple, sharp-lined 2D animation in the manner of a pastel-softened “BoJack Horseman.”

Both the film’s aesthetic and its wordless approach, however, are rooted in American author and illustrator Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel of the same name. Where Varon’s work was primarily targeted at young readers, the audience for Berger’s film — suffused with nostalgia for a Reagan-era New York of roller discos and boomboxes on the sidewalks — is a little harder to pin down. It’s certainly clean enough for kids, with little of the snark or cynicism that drives similarly hip-looking adult animation, though small fry might be perplexed by its drifting, low-incident narrative and overriding air of melancholy. Still, it’s in such odd, in-between niches that cult items can bloom; already well-received at such festivals at Cannes and Annecy, “Robot Dreams” should build a sufficient following to prove its own message to the lonely and forlorn: when it comes to love, quality trumps quantity.

More from Variety

Annecy Prizes: 'Chicken for Linda!,' 'Robot Dreams,' 'Pebble Hill' Take Top Honors

Top Titles from Spain at Cannes 2023

Neon Makes First Cannes Acquisition With Pablo Berger's Animated 'Robot Dreams'

What kind of love, exactly, is the most intriguing question in a tale that hints at a degree of queer companionship between its two seemingly (though not definitively) male-gendered principals, all while remaining wholesomely chaste. (Given they’re a dog and a mechanical robot, it’s hard to imagine how things could be otherwise.) Unnamed protagonist Dog is introduced living a solitary life in the East Village, following a fixed routine of work, walks and glumly microwaved TV dinners — paid no mind by anyone, save the pigeons crowding around his apartment window. He’s a stoic soul, but everyone has a limit: Late one night, inspired by an infomercial on his ever-blaring television set, he orders a flatpack build-your-own-robot-kit, promoted in much the same manner as a set of Ginsu steak knives.

Whatever it costs, it’s worth it. From the moment of assembly, the unnamed Robot improbably turns out to be a most affectionate and responsive compadre, forever fixated on his canine owner with a metallic grin and perma-wide eyes. He’s not much of a conversationalist, but then neither is Dog. Their summer days are spent sightseeing, sunbathing, hotdog-eating, rollerskating through Central Park — generally taking Manhattan in more or less the manner Cole Porter described decades before, though their special song is Earth, Wind and Fire’s “September.” That ever-elastic disco nugget soundtracks multiple buddy montages of varying mood and motion: Its ebullience matches the effervescent early stages of their friendship, only to gradually become an ironic counterpoint in a story of loss and subconscious yearning.

For September comes, and with it, separation: After a day’s gambolling at Coney Island, Robot’s sea-soaked joints swiftly rust, rendering him immobile. Unable to carry his pal home, and with the beach thereafter closed for the winter, Dog must endure the winter alone — all while the abandoned Robot withers and freezes in the cold, his parts plundered by piratical critters. Only in multiple dream sequences (thus part-answering Philip K. Dick’s burning question about androids, though no electric sheep are in evidence) can he attempt a reunion with Dog. Spring will come, as will some manner of closure, though it’s fair to say the uncompromised joys of the film’s opening acts are never regained. Counter to happily-ever-after endings of the Disney variety, “Robot Dreams” embraces the pleasingly mature philosophy that there can be more than one soulmate in an individual’s life, and that a finite relationship isn’t a failed one.

It’s a poignant arc that perhaps isn’t quite robust enough to power a 100-minute feature given to rhythmic and narrative repetition. “Robot Dreams” would have been no less effective or affecting as a short subject, though that format would have admittedly kerbed the gleeful volume of nifty visual gags that Berger packs around his sweet, slender story — many of them wittily attuned to the period (frozen food and advertising trends of the era come in for a good ribbing) and the anything-goes street life of New York itself. Above all else, Berger’s film delights in the kind of eccentric, incidental sights and sounds from which dreams — human, animal or android — can spring.

No comments:

Post a Comment