ARCHAEOLOGY

‘Semi-buried boulders’ near 3,000-year-old Italy village stumped experts — until nowMoira Ritter

Fri, January 5, 2024

About 50 years ago, archaeologists began exploring the ancient ruins of a 3,000-year-old island village in Italy. Initial investigations included aerial photographs, which showed peculiar “semi-buried boulders” on the outskirts of the settlement.

Experts have struggled to determine why the boulders were there — until now.

A new study found that the boulders were once part of a “complex” fortification system, serving as a first layer of defense for the already enclosed village, according to a study published in the January volume of the Journal of Applied Geophysics.

An aerial photo from 1968 showing the boulders outside of the village.

The remnants of the wall were discovered outside the village of Faraglioni, which was established on the volcanic island of Ustica around 1400 B.C., archaeologists said. The village was mysteriously abandoned around 1200 B.C.

Experts consider the site one of the best-preserved Mediterranean settlements of the Bronze Age, according to a Jan. 5 release from the Austria Press Agency. The village had a sophisticated urban layout, with dozens of huts lining narrow streets.

The village was positioned on the edge of a cliff, so one side was naturally protected by the cliffside and ocean. The inland edge of the village was guarded by a “massive fortified wall” that is still standing, archaeologists said.

The village’s inner “enclosing” wall spans about 820 feet, experts said.

Researchers said the “mighty curved” wall is about 820 feet long and 13 feet tall. It resembles a “fish hook” and connects to the huts through a passage.

The peculiar boulders were found about 20 feet from the standing inner wall, “discontinuously” following the same structure and shape of the inner wall, the study said. Archaeologists also discovered the remains of a tower between the standing wall and the boulders that appears to be connected to both structures.

A graphic shows the interior wall on the left and the remains of the exterior wall on the right.

A tower found between the ruins of the two walls.

Using photographs and various survey methods, it was determined that the boulders were actually remnants of an exterior wall that likely served as a first defense for the huge Bronze Age settlement, according to experts.

Archaeologists used non-invasive methods to study the boulders.

“The defensive system of the Faraglioni Middle Bronze Age village at Ustica consisted of two main elements: a large peripheral outwork, and an internal wall reinforced by buttresses, both having an arched design and mutually distant (19 to 22 feet),” archaeologists said. “Their construction was aimed at isolating the marine terrace and the village from the Tramontana plain.”

Archaeologists said the defense system’s purpose was likely two-fold: It defended the village while also establishing the settlement’s borders and creating a social structure.

Ustica is an island north of Sicily, which is in southern Italy.

Google Translate was used to translate a release from the Austria Press Agency.

Dig at ancient cemetery reveals colorful masks and artifacts. See the finds from Egypt

Aspen Pflughoeft

Thu, January 4, 2024

Forgotten by time and obscured by the desert, a collection of ancient burials — and their treasures — went unnoticed in Egypt. Not anymore.

A joint team of Egyptian and Japanese archaeologists excavated part of the Saqqara archaeological site and unearthed an ancient cemetery, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a Jan. 4 Facebook post.

The cemetery included several burials, a tomb and a poorly preserved coffin, archaeologists said. Several of the graves had colorful masks that represented the deceased person’s face.

One of the burials found at the Saqqara site.

Photos show several of these burial masks and one skeleton next to the mask of its face.

One of the burial masks found at the Saqqara site.

Archaeologists also found several other artifacts including religious pendants, or amulets, statues of goddesses, vases and pieces of pottery at the cemetery, the release said.

A burial masks found at the Saqqara site.

The graves and their contents spanned several ancient eras, archaeologists said.

The cemetery and its oldest finds dated to the Second Dynasty, a period that ended over 4,600 years ago, according to the World History Encyclopedia. The most recent finds dated to the Ptolemaic era, a period that ended about 2,000 years ago.

One of the burials found at Saqqara.

The Saqqara archaeological site is about 5 miles long and the cemetery of the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis, according to Britannica. The site includes the Step Pyramid of Djoser, the burial site of a king who ruled over 4,500 years ago.

One of the skeletons found at Saqqara.

Excavations are ongoing.

The Saqqara archaeological site is about 15 miles southwest of Cairo.

Google Translate was used to translate the Facebook post from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Ancient Egyptian teenager died while giving birth to twins, mummy reveals

Sascha Pare

Thu, January 4, 2024

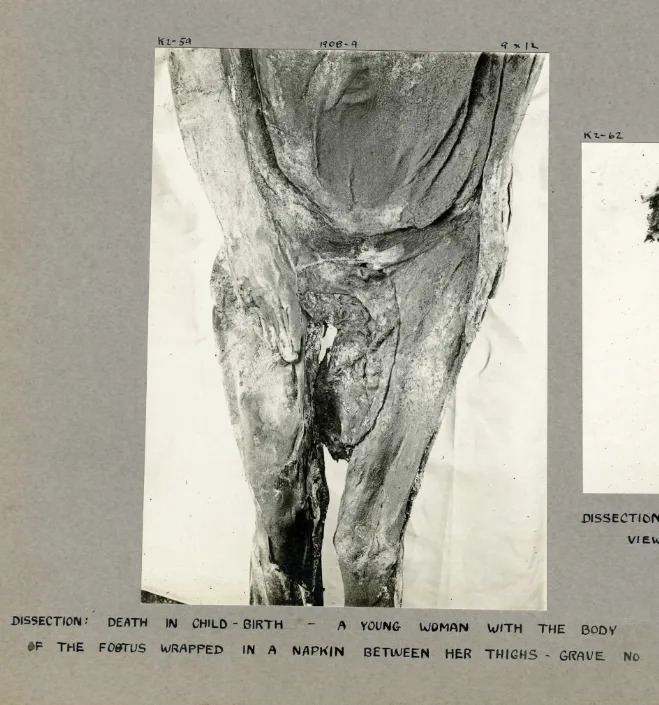

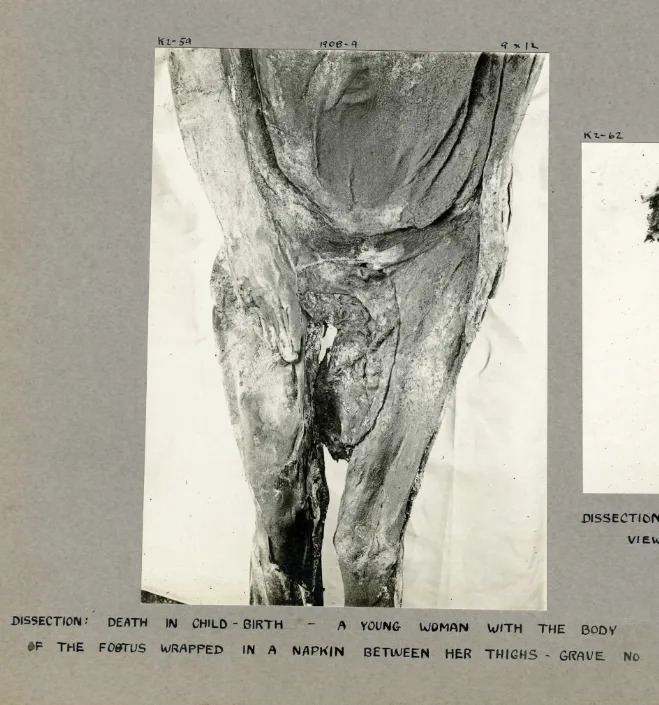

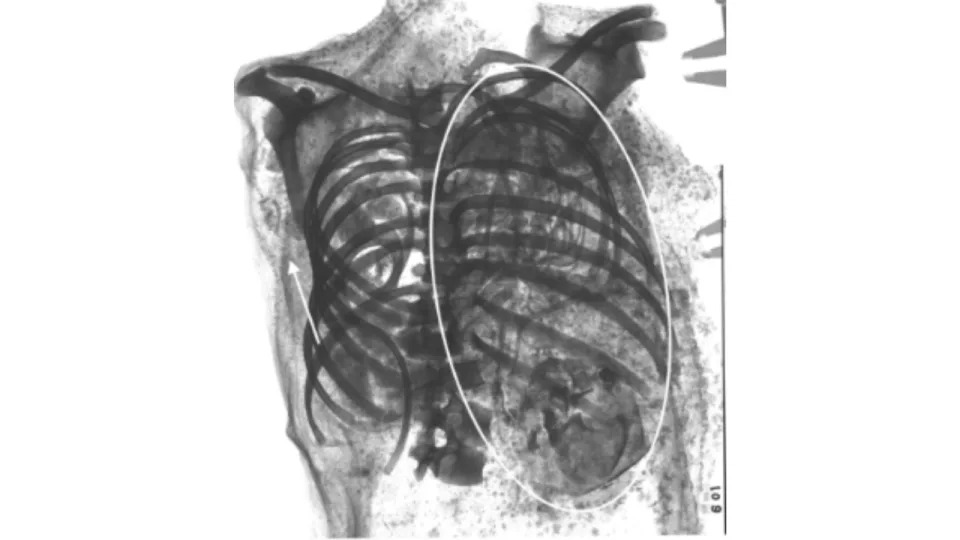

Two photographs show the mummy's incised abdomen and the fetus' head lodged in the pelvic cavity.

The ancient remains of an unborn fetus found in the headless mummy of an Egyptian teenager shows she died while giving birth to twins, a new study confirms.

When archaeologists excavated and unwrapped the mummy in 1908, they discovered the bandaged body of a fetus and the remains of a placenta wedged between the girl's legs. Field notes from the time reveal the researchers concluded the fetus was related to the mummified female — a girl between 14 and 17 years old who lived in ancient Egypt sometime between the Late Dynastic (from around 712 to 332 B.C.) and Coptic period (between A.D 395 and 642). Researchers incised the mother's abdomen and found the fetus' skull stuck in the birth canal, indicating the girl had died from complications during childbirth.

But it wasn't until a century later that researchers discovered a second fetus, this time mysteriously lodged in the girl's chest.

"This is the first mummy of its kind discovered," said study lead author Francine Margolis, a U.S.-based independent archaeologist. While there are many known burials of women who died in childbirth in the archaeological record, "there has never been one found in Egypt," Margolis told Live Science in an email.

Related: Ancient Egyptian children were plagued with blood disorders, mummies reveal

In 2021, researchers announced the discovery of a pregnant Egyptian mummy, but other experts challenged the results and concluded the woman wasn't pregnant when she died in a 2022 study.

A picture of the mummy with a fetus lodged between its legs.

Margolis first studied the mummy excavated in 1908 while writing her master's thesis in anthropology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, D.C. on female pelvic morphology in 2019. "I CT scanned her to obtain her pelvic measurements," Margolis said. "That is when we discovered the second fetus."

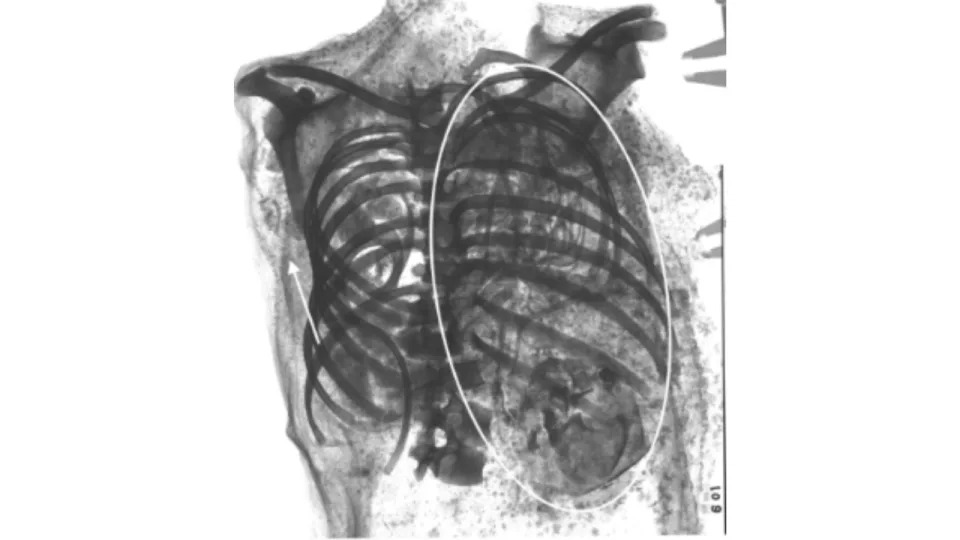

The 3D images showed that the remains of a fetus, which no previous records mentioned, had become lodged in the girl's chest. Margolis and David Hunt, co-author of the new study and an anthropologist at GWU, X-rayed the mummy to obtain a clearer picture of the fetal remains.

"When we saw the second fetus we knew we had a unique find and a first for ancient Egyptian archaeology," Margolis said.

An X-ray scan of the mummy's torso showing the remains of a fetus.

For the new study, published Dec. 21 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, the researchers re-examined the mummy's torso and the external fetus to confirm the teenager's cause of death. They also reviewed and compiled notes and photographs taken during the 1908 excavations.

Margolis and Hunt found that the girl died in labor after the head of the first fetus became trapped in the birth canal, she said. The head of a fetus exiting the womb during childbirth is usually tucked to its chest to enable passage through the pelvis, according to the study. The researchers think that in this case, the fetus' head was untucked in a position that was too broad to get through and became stuck.

Results from the 2019 analysis showed the mother stood around 5 feet tall (1.52 meters) and weighed between 100 and 120 pounds (45 to 55 kilograms). Her small size and young age may have contributed to her unsuccessful delivery of the twins, the researchers noted in the new study.

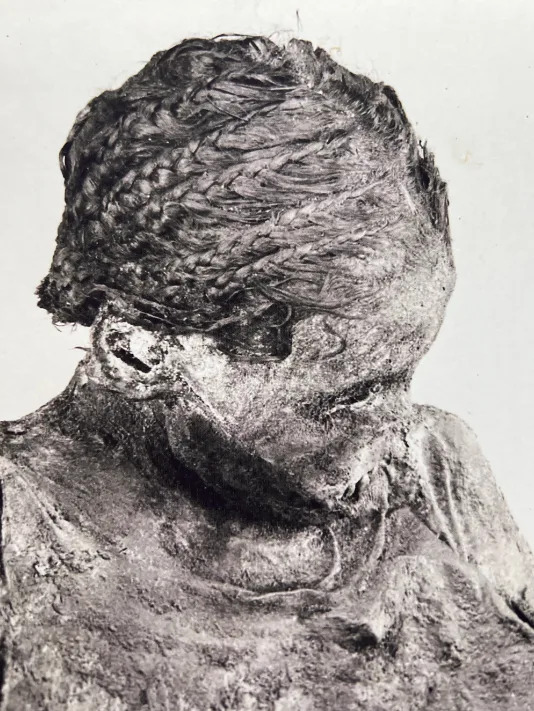

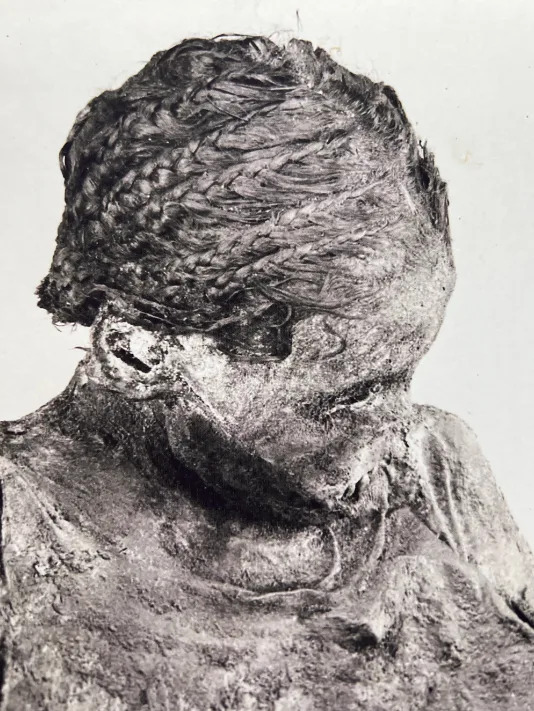

The missing head of the mummy, photographed in 1908.

The mother's mummified head is missing, which limits the researchers' knowledge of her health, Margolis said. "If we found her head and her teeth are present, destructive testing on teeth and hair could provide information on her diet and metabolic stress she was experiencing during her life," she said.

RELATED STORIES

—Ancient Egyptian cemetery holds rare 'Book of the Dead' papyrus and mummies

—Stunning CT scans of 'Golden Boy' mummy from ancient Egypt reveal 49 hidden amulets

—Egyptian mummies covered in gold are rare, and we may have just found the oldest

It's also unclear how the remains of the second fetus ended up in the girl's chest. The researchers suggested the diaphragm and other tissues likely dissolved during the mummification process, enabling the small body to migrate upward.

Childbirth in ancient Egypt is poorly documented, according to the study, but existing records suggest twins were undesirable. A papyrus from the third intermediate period (1070 to 713 B.C.), known as the Oracular Amuletic Decree, offered mothers a spell intended to prevent twin births.

Aspen Pflughoeft

Thu, January 4, 2024

Forgotten by time and obscured by the desert, a collection of ancient burials — and their treasures — went unnoticed in Egypt. Not anymore.

A joint team of Egyptian and Japanese archaeologists excavated part of the Saqqara archaeological site and unearthed an ancient cemetery, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a Jan. 4 Facebook post.

The cemetery included several burials, a tomb and a poorly preserved coffin, archaeologists said. Several of the graves had colorful masks that represented the deceased person’s face.

One of the burials found at the Saqqara site.

Photos show several of these burial masks and one skeleton next to the mask of its face.

One of the burial masks found at the Saqqara site.

Archaeologists also found several other artifacts including religious pendants, or amulets, statues of goddesses, vases and pieces of pottery at the cemetery, the release said.

A burial masks found at the Saqqara site.

The graves and their contents spanned several ancient eras, archaeologists said.

The cemetery and its oldest finds dated to the Second Dynasty, a period that ended over 4,600 years ago, according to the World History Encyclopedia. The most recent finds dated to the Ptolemaic era, a period that ended about 2,000 years ago.

One of the burials found at Saqqara.

The Saqqara archaeological site is about 5 miles long and the cemetery of the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis, according to Britannica. The site includes the Step Pyramid of Djoser, the burial site of a king who ruled over 4,500 years ago.

One of the skeletons found at Saqqara.

Excavations are ongoing.

The Saqqara archaeological site is about 15 miles southwest of Cairo.

Google Translate was used to translate the Facebook post from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Ancient Egyptian teenager died while giving birth to twins, mummy reveals

Sascha Pare

Thu, January 4, 2024

Two photographs show the mummy's incised abdomen and the fetus' head lodged in the pelvic cavity.

The ancient remains of an unborn fetus found in the headless mummy of an Egyptian teenager shows she died while giving birth to twins, a new study confirms.

When archaeologists excavated and unwrapped the mummy in 1908, they discovered the bandaged body of a fetus and the remains of a placenta wedged between the girl's legs. Field notes from the time reveal the researchers concluded the fetus was related to the mummified female — a girl between 14 and 17 years old who lived in ancient Egypt sometime between the Late Dynastic (from around 712 to 332 B.C.) and Coptic period (between A.D 395 and 642). Researchers incised the mother's abdomen and found the fetus' skull stuck in the birth canal, indicating the girl had died from complications during childbirth.

But it wasn't until a century later that researchers discovered a second fetus, this time mysteriously lodged in the girl's chest.

"This is the first mummy of its kind discovered," said study lead author Francine Margolis, a U.S.-based independent archaeologist. While there are many known burials of women who died in childbirth in the archaeological record, "there has never been one found in Egypt," Margolis told Live Science in an email.

Related: Ancient Egyptian children were plagued with blood disorders, mummies reveal

In 2021, researchers announced the discovery of a pregnant Egyptian mummy, but other experts challenged the results and concluded the woman wasn't pregnant when she died in a 2022 study.

A picture of the mummy with a fetus lodged between its legs.

Margolis first studied the mummy excavated in 1908 while writing her master's thesis in anthropology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, D.C. on female pelvic morphology in 2019. "I CT scanned her to obtain her pelvic measurements," Margolis said. "That is when we discovered the second fetus."

The 3D images showed that the remains of a fetus, which no previous records mentioned, had become lodged in the girl's chest. Margolis and David Hunt, co-author of the new study and an anthropologist at GWU, X-rayed the mummy to obtain a clearer picture of the fetal remains.

"When we saw the second fetus we knew we had a unique find and a first for ancient Egyptian archaeology," Margolis said.

An X-ray scan of the mummy's torso showing the remains of a fetus.

For the new study, published Dec. 21 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, the researchers re-examined the mummy's torso and the external fetus to confirm the teenager's cause of death. They also reviewed and compiled notes and photographs taken during the 1908 excavations.

Margolis and Hunt found that the girl died in labor after the head of the first fetus became trapped in the birth canal, she said. The head of a fetus exiting the womb during childbirth is usually tucked to its chest to enable passage through the pelvis, according to the study. The researchers think that in this case, the fetus' head was untucked in a position that was too broad to get through and became stuck.

Results from the 2019 analysis showed the mother stood around 5 feet tall (1.52 meters) and weighed between 100 and 120 pounds (45 to 55 kilograms). Her small size and young age may have contributed to her unsuccessful delivery of the twins, the researchers noted in the new study.

The missing head of the mummy, photographed in 1908.

The mother's mummified head is missing, which limits the researchers' knowledge of her health, Margolis said. "If we found her head and her teeth are present, destructive testing on teeth and hair could provide information on her diet and metabolic stress she was experiencing during her life," she said.

RELATED STORIES

—Ancient Egyptian cemetery holds rare 'Book of the Dead' papyrus and mummies

—Stunning CT scans of 'Golden Boy' mummy from ancient Egypt reveal 49 hidden amulets

—Egyptian mummies covered in gold are rare, and we may have just found the oldest

It's also unclear how the remains of the second fetus ended up in the girl's chest. The researchers suggested the diaphragm and other tissues likely dissolved during the mummification process, enabling the small body to migrate upward.

Childbirth in ancient Egypt is poorly documented, according to the study, but existing records suggest twins were undesirable. A papyrus from the third intermediate period (1070 to 713 B.C.), known as the Oracular Amuletic Decree, offered mothers a spell intended to prevent twin births.

No comments:

Post a Comment