UPDATED

Julian Assange appeals in ‘most important press freedom case in the world’

A court will decide if Julian Assange may appeal extradition to the US, where relatives say he could die in jail.

By John Psaropoulos

Published On 20 Feb 2024

London’s High Court has scheduled two days of hearings on Tuesday and Wednesday to decide whether WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange may appeal a United States request for extradition to stand trial on espionage charges.

Those charges carry maximum penalties of 175 years, but the real danger, says Assange’s wife Stella, is that he may suffer an inadvertent death penalty instead.

“His health is in decline, physically and mentally,” Stella Assange recently told reporters. “His life is at risk every single day he stays in prison, and if he’s extradited, he will die.”

If Wednesday’s decision goes against Assange, his legal team plans to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights – though a favourable ruling there may not come in time to stop an extradition.

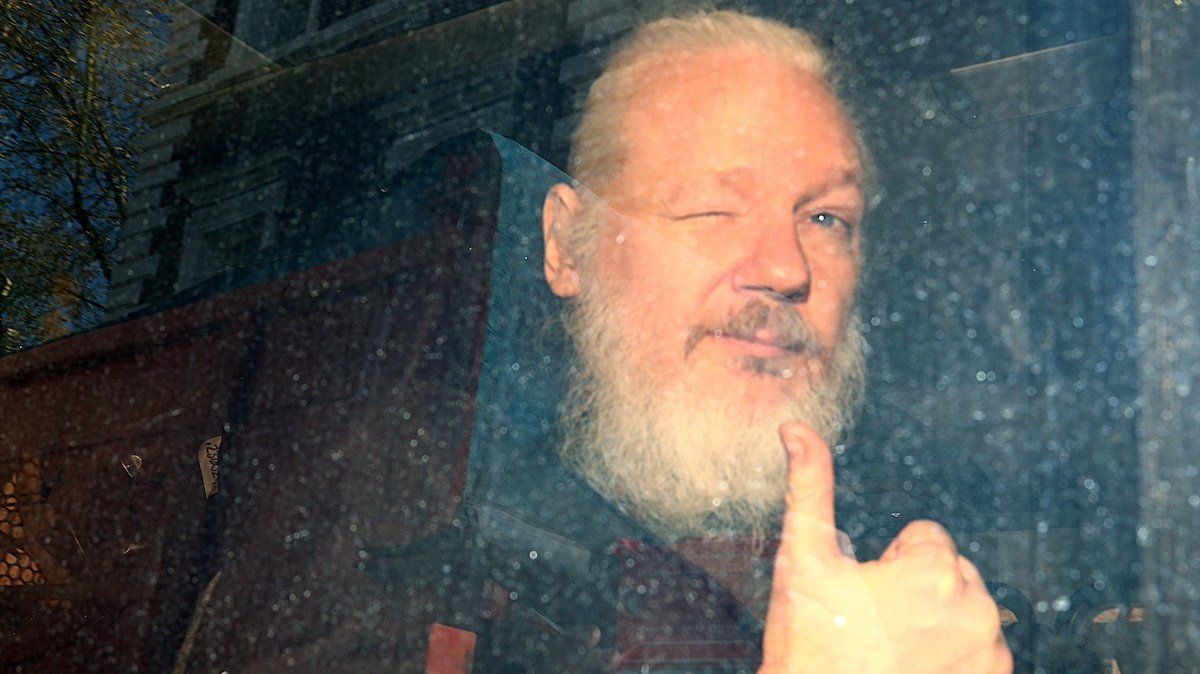

Assange will not attend court due to illness, his lawyers said on Tuesday.

A British judge agreed in January 2021, ruling he should not be extradited to the US because he was likely to commit suicide in near total isolation.

“I find that the mental condition of Mr. Assange is such that it would be oppressive to extradite him to the United States of America,” judge Vanessa Baraitser said.

But the US has continued to press for his extradition.

The 17 charges of espionage from a district court in East Virginia stem from Assange’s publication in 2010 of hundreds of thousands of pages of classified US military documents on his website, WikiLeaks.

US prosecutors say Assange conspired with US intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning to hack the Pentagon’s servers to retrieve the documents.

The files, widely reported in Western media, revealed evidence of what many consider to be war crimes committed by US forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. They include video of a 2007 Apache helicopter attack in Baghdad that killed 11 people, including two Reuters journalists.

‘The most important press freedom case in the world’

Since it came to prominence in 2010, Wikileaks has become a repository for documentary evidence uncovered by government or corporate whistleblowers.

In 2013, Edward Snowden, a contractor with the US National Security Agency, leaked documents to WikiLeaks revealing that the NSA had installed digital stovepipes in the servers of email providers, and was secretly filtering private correspondence.

Three years later, millions of documents were leaked from the Panamanian offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca, revealing that corporations and public officials had set up offshore companies to evade taxes and hide money that could be used for illicit purposes.

Snowden called Assange’s case “the most important press freedom case in the world” on X, formerly Twitter, and legal experts agree.

“This case is the first in which the US government has relied on the 1917 Espionage Act as the basis for the prosecution of a publisher,” Jameel Jaffer, a professor of law and journalism at Columbia University, told Al Jazeera.

“A successful prosecution of Assange on the basis of this indictment would criminalise a great deal of the investigative journalism that is absolutely crucial to democracy,” Jaffer said, including cultivating sources, communicating with them confidentially, soliciting information from them, protecting their identities from disclosure, and publishing classified information.

“I really can’t imagine why the Biden administration would want this dangerous, short-sighted prosecution to be part of its legacy. The Justice Department should drop the Espionage Act charges, which should never have been filed in the first place.”

Although the leak happened in 2010, Assange was not prosecuted by the administration of Barack Obama, then in power.

The prosecution came from the administration of Donald Trump eight years later, and US President Joe Biden seems to be doubling down on it.

Stella Assange argued that her husband acted as a publisher in posting information beneficial to the public, and publishers have customarily not been prosecuted for doing their job.

“Julian has been indicted for receiving, possessing and communicating information to the public of evidence of war crimes committed by the US government,” Stella Assange said. “Reporting a crime is never a crime.”

But US prosecutors say he was not merely the receiver of information.

“Assange agreed to assist Manning in cracking a password stored on United States Department of Defence computers,” his indictment says. Helping to hack the Pentagon’s servers was a crime of commission that also put US intelligence sources at risk and “could be used to the injury of the United States”, said prosecutors.

‘He’s suffered enough’

In addition to upholding fundamental press freedoms, Assange’s friends and family have argued that he should be released from the charges on humanitarian grounds.

Assange has already spent seven years in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, where he sought asylum, and since 2019 has been in London’s high-security Belmarsh Prison.

Assange’s allies consider that his 11 years of imprisonment amount to punishment enough.

WikiLeaks editor Kristinn Hrafnsson called it “punishment through process”.

“It is obviously a deliberate attempt to wear him down to punish him by taking this long,” Hrafnsson recently told reporters.

Julian and Stella Assange have two sons conceived while he lived in the Ecuadorean embassy, who have only met their father behind bars.

The government of Assange’s native Australia has also asked for a rapid conclusion to the gruelling legal process.

On February 14, the federal parliament in Canberra passed a resolution supporting that Assange’s 2010 leak had “revealed shocking evidence of misconduct by the USA” and underlining “the importance of the UK and USA bringing the matter to a close so that Mr Assange can return home to his family in Australia”.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese pointed out that the resolution had the support of diverse political forces that “would have a range of views about the merits of Mr Julian Assange’s actions”.

Yet, he said, “they have come to the common view … that enough is enough and that it is time for this to be brought to a close”.

Australia “has sought to advance that position by making appropriate diplomatic representations,” Donald Rothwell, a professor of international law at the Australian National University, told Al Jazeera. “However, its ability to advance that is limited by the fact that legally and politically the matter really rests with the UK and US.”

The US also pursues Snowden under the 1917 Espionage Act, but “because he is currently a Russian citizen and living in Russia he is effectively protected from US prosecution because Russia will not extradite him,” said Rothwell.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

Julian Assange begins last-ditch battle to stop extradition to US

Sam Tobin and Michael Holden

Feb 20, 2024,

"Julian needs his freedom and we all need the truth," Julian Assange's wife Stella told protesters in London on Tuesday.

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is about to begin what could be his last chance to stop his extradition from Britain to the United States after more than 13 years battling the authorities in the English courts.

US prosecutors are seeking to put Assange, 52, on trial on 18 counts relating to WikiLeaks’ high-profile release of vast troves of confidential US military records and diplomatic cables.

They argue the leaks imperilled the lives of their agents and there is no excuse for his criminality.

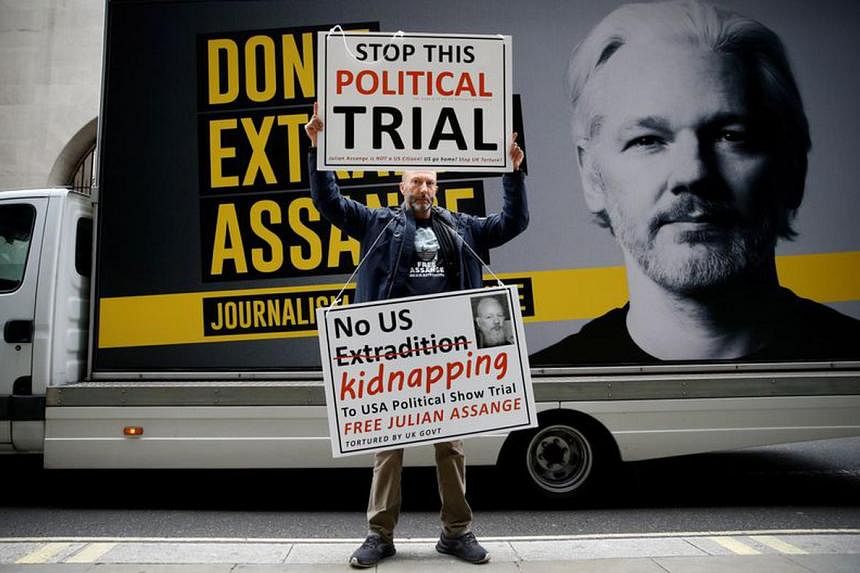

Assange’s supporters hail him as an anti-establishment hero and a journalist, who is being persecuted for exposing US wrongdoing.

Outside the High Court in London, a large, noisy crowd gathered, chanting “Only one decision, no extradition”.

“We have two big days ahead. We don’t know what to expect, but you are here because the world is watching,” Assange’s wife Stella told the crowd.

“They have to know they can’t get away with this. Julian needs his freedom and we all need the truth.”

Assange’s legal battles began in 2010, and he subsequently spent seven years holed up in Ecuador’s embassy in London before he was dragged out and jailed in 2019 for breaching bail conditions.

He has been held in a maximum-security jail in southeast London ever since, even getting married there.

Britain finally approved his extradition to the US in 2022 after a judge initially blocked it because concerns about his mental health meant he would be at risk of suicide if deported.

His lawyers will try to overturn that approval at a two-day hearing in front of two judges in what could be his last chance to stop his extradition in the English courts.

They will argue that Assange’s prosecution is politically motivated and marks an attack on free speech, as the first time a publisher has been charged under the US Espionage Act.

Assange’s supporters include Amnesty International, media groups that worked with WikiLeaks and politicians in his country of birth Australia, including Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who last week voted in favour of a motion calling for his return to Australia.

If Assange wins this case, a full appeal hearing will be held to again consider his challenge.

If he loses, his only remaining option would be at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) where he has an appeal lodged pending the London ruling.

Speaking last week, Stella Assange said the decision was a matter of life and death and his lawyers would apply to the ECHR for an emergency injunction if necessary.

“His health is in decline, physically and mentally,” she said. “His life is at risk every single day he stays in prison – and if he is extradited he will die.”

Assange’s brother Gabriel Shipton compared the WikiLeaks founder with Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition activist who died in prison on Friday while serving a three-decade sentence.

WikiLeaks first came to prominence in 2010 when it published a US military video showing a 2007 attack by Apache helicopters in Baghdad that killed a dozen people, including two Reuters news staff.

It then released thousands of secret classified files and diplomatic cables that laid bare often highly critical US appraisals of world leaders from Russian President Vladimir Putin to members of the Saudi royal family.

-Reuters, with AP

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange's final bid

to contest extradition to US begins amid

protests

Should this legal recourse falter, Assange would exhaust all available avenues for appeal within UK legal system, consequently triggering extradition process

Aysu Bicer |20.02.2024

LONDON

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is facing what could potentially be his last chance to contest his extradition from the UK to the US as a two-day hearing commences Tuesday amid fervent protests outside the Royal Courts of Justice.

Assange, detained in a UK prison since 2019, faces extradition over allegations of leaking classified military documents between 2010 and 2011.

The UK High Court, in a pivotal ruling in 2021, decreed that Assange should be extradited, disregarding assertions regarding his fragile mental state and the potential risks he might face in a US correctional facility.

Following suit, the Supreme Court in 2022 upheld this decision, while then-Home Secretary Priti Patel affirmed the extradition order, intensifying the legal battle.

In his latest bid for reprieve, Assange is seeking authorization to scrutinize Patel's determination and challenge the initial 2021 court verdict.

Should this legal recourse falter, Assange would exhaust all available avenues for appeal within the UK legal system, consequently triggering the extradition process.

Meanwhile, outside the Royal Courts of Justice, supporters of Assange have gathered in solidarity, brandishing banners that read "Free Assange" and "Free journalism."

'America is war criminal'

Esla, one of the protesters who only gave her first name, said: "All of us we are here because we want Julian Assange free today. Julian Assange represents the truth of the press and our right to know. Release Julian Assange from prison to see sunlight for the first time."

"After so many years of psychological torture, to be with his wife, his little children, his friends, his family, and all of us, and Julian Assange can continually bring us the truth. We need truth more than ever," she added.

Another supporter, who did not want to be named, condemned actions of the US, stating: "America should be in the dark, America is a war criminal, the worst rogue terrorist state there is. They've been prosecuting wars for years."

"They are terrible the way about what they do. Helicopter gunships killing people all over the Middle East. Julian Assange has published this, which we all need to know because it's our taxes that go to support these wars, for oil for business contracts. And he's just he's just presented the truth through WikiLeaks. And now he's in prison. What's he done? He's done nothing. He's a publisher, a journalist, and this is journalism in prison," he added.

Assange steadfastly maintains that the accusations against him are politically motivated, a claim echoed by his legal team. They have hinted at a potential recourse to the European Court of Human Rights should the UK appeal fall short.

LONDON (AP) — WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been fighting for more than a decade to avoid extradition to the United States to face charges related to his organization’s publication of a huge trove of classified documents. He has been in custody in a high-security London prison since 2019, and previously spent seven years in self-exile in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London.

WATCH: Wikileaks founder Julian Assange makes last-ditch attempt to avoid U.S. extradition

As his lawyers begin a final round of legal challenge Tuesday to stop him from being sent from Britain to the U.S., here is a look at key events in the long-running legal saga:

2006

Assange founds WikiLeaks in Australia. The group begins publishing sensitive or classified documents.

2010

In a series of posts, WikiLeaks released almost half a million documents relating to the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

August

Swedish prosecutors issue an arrest warrant for Assange based on one woman’s allegation of rape and another’s allegation of molestation. The warrant is withdrawn shortly afterward, with prosecutors citing insufficient evidence for the rape allegation. Assange denies the allegations.

September

Sweden’s director of prosecutions reopens the rape investigation. Assange leaves Sweden for Britain.

November

Swedish police issue an international arrest warrant for Assange.

December

Assange surrenders to police in London and is detained pending an extradition hearing. High Court grants Assange bail.

2011

February

District court in Britain rules Assange should be extradited to Sweden.

2012

June

Assange enters Ecuadorian Embassy in central London, seeking asylum on June 19, after his bids to appeal the extradition ruling failed. Police set up round-the-clock guard to arrest him if he steps outside.

August

Assange is granted political asylum by Ecuador.

2014

July

Assange loses his bid to have an arrest warrant issued in Sweden against him canceled. A judge in Stockholm upholds the warrant alleging sexual offences against two women.

2015

March

Swedish prosecutors ask to question Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy.

August

Swedish prosecutors drop investigations into some allegations against Assange because of the statute of limitations; an investigation into a rape allegation remains active.

October

Metropolitan Police end their 24-hour guard outside the Ecuadorian embassy but say they’ll arrest Assange if he leaves, ending a three-year police operation estimated to have cost millions.

2016

February

Assange claims “total vindication” as the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention finds that he has been unlawfully detained and recommends he be immediately freed and given compensation. Britain calls the finding “frankly ridiculous.”

2018

September

Ecuador’s president says his country and Britain are working on a legal solution to allow Assange to leave the embassy.

October

Assange seeks a court injunction pressing Ecuador to provide him basic rights he said the country agreed to when it first granted him asylum.

November

A U.S. court filing that appears to inadvertently reveal the existence of a sealed criminal case against Assange is discovered by a researcher. No details are confirmed.

2019

April

Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno blames WikiLeaks for recent corruption allegations; Ecuador’s government withdraws Assange’s asylum status. London police arrest Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy for breaching bail conditions in 2012, as well as on behalf of U.S. authorities.

May

Assange is sentenced to 50 weeks in prison for jumping bail in 2012.

May

The U.S. government indicts Assange on 18 charges over WikiLeaks’ publication of classified documents. Prosecutors say he conspired with U.S. army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning to hack into a Pentagon computer and release secret diplomatic cables and military files on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

November

Swedish prosecutor drops rape investigation.

2020

May

An extradition hearing for Assange is delayed amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

June

The U.S. files new indictment against Assange that prosecutors say underscores Assange’s efforts to procure and release classified information.

2021

January

A British judge rules Assange cannot be extradited to the U.S. because he is likely to kill himself if held under harsh U.S. prison conditions.

July

The High Court grants the U.S. government permission to appeal the lower court’s ruling blocking Assange’s extradition.

December

The High Court rules that U.S. assurances about Assange’s detention are enough to guarantee he would be treated humanely.

2022

March

Britain’s top court refuses to grant Assange permission to appeal against his extradition.

June

Britain’s government orders the extradition of Assange to the United States. Assange appeals.

2024

Feb. 20

Assange’s lawyers launch a final legal bid to stop his extradition at the High Court.

RelatedWikiLeaks founder Assange begins final attempt to avoid extradition to U.S.

By Jill Lawless, Associated Press

Assange lawyer dismisses U.S. promises over extradition

By Sylvia Hui, Associated Press

WikiLeaks founder Assange denied bail in UK

Assange vs. America, again

FEB 20, 2024

LONDON - WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange begins what could be his last chance to stop his extradition from Britain to the United States on Tuesday after more than 13 years battling the authorities in the English courts.

U.S. prosecutors are seeking to put Assange, 52, on trial on 18 counts relating to WikiLeaks' high-profile release of vast troves of confidential U.S. military records and diplomatic cables.

They argue the leaks imperilled the lives of their agents and there is no excuse for his criminality. Assange's many supporters hail him as an anti-establishment hero and a journalist, who is being persecuted for exposing U.S. wrongdoing and committing alleged war crimes.

Assange's legal battles began in 2010, and he subsequently spent seven years holed up in Ecuador's embassy in London before he was dragged out and jailed in 2019 for breaching bail conditions. He has been held in a maximum-security jail in southeast London ever since, even getting married there.

Britain finally approved his extradition to the U.S. in 2022 after a judge initially blocked it because concerns about his mental health meant he would be at risk of suicide if deported.

His lawyers will try to overturn that approval at a two-day hearing in front of two judges at London's High Court in what could be his last chance to stop his extradition in the English courts. His wife Stella last week described it as a matter of life and death.

They will argue that Assange's prosecution is politically motivated and marks an impermissible attack on free speech, as the first time a publisher has been charged under the U.S. Espionage Act.

His supporters include Amnesty International, Reporters Without Borders, media organisations which worked with WikiLeaks and Australian politicians, including Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who last week voted in favour of a motion calling for his return to Australia.

Pope Francis even granted his wife an audience last year.

'HE WILL DIE'

If Assange wins permission in the latest case, a full appeal hearing will be held to again consider his challenge. If he loses, his only remaining option would be at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) where he has an appeal already lodged pending the London ruling.

Speaking last week, Stella Assange said they would apply to the ECHR for an emergency injunction if necessary. She said her husband would not survive if he was extradited.

"His health is in decline, physically and mentally," she said. "His life is at risk every single day he stays in prison – and if he is extradited he will die."

Assange's brother Gabriel Shipton compared the WikiLeaks founder with Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition activist who died in prison on Friday while serving a three-decade sentence.

"I know exactly what it feels like to have a loved one unjustly incarcerated with no hope," he told the BBC. "To have them pass away, that's what we live in fear of: that Julian will be lost to us, lost to the U.S. prison system or even die in jail in the UK."

WikiLeaks first came to prominence in 2010 when it published a U.S. military video showing a 2007 attack by Apache helicopters in Baghdad that killed a dozen people, including two Reuters news staff.

It then released thousands of secret classified files and diplomatic cables that laid bare often highly critical U.S. appraisals of world leaders from Russian President Vladimir Putin to members of the Saudi royal family.

REUTERS

'Belief in consent' could soon be gone

by The Canary

19 February 2024

On 21 February at the Royal Courts of Justice, London, on the application of the Attorney General, the Court of Appeal will consider whether to remove the last remaining legal defence for many activists: the belief that the owners of property would have consented to the damage caused if they fully understood the circumstances. It is commonly known as “belief in consent“.

Until recently, it was almost unheard of for the government to interfere with legally available defences in this way.

However, following the acquittal of the Colston Four – who toppled the statue of slave trader Edward Colston into Bristol harbour – Attorney General Victoria Prentis’ predecessor Suella Braverman made a similar intervention to prevent such a verdict being repeated in the future, which the Court of Appeal supported.

Pattern of acquittals based on belief in consent

Despite this, and other decisions of the higher courts, removing otherwise available defences (such as ‘necessity’), juries have continued to find ways to acquit people whose fundamental argument is that they are taking proportionate and necessary action to prevent a far greater harm.

In just the last few months of 2023, there were a number of high profile acquittals of activists based on belief in consent, including:A group who sprayed the Treasury with fake blood, to draw attention to the scale of UK Export Finance’s investments in fossil fuels around the world.

Nine women who broke windows at HSBC to shine a spotlight on HSBC’s £80bn financing of fossil fuel projects since the Paris Agreement.

Members of Palestine Action, who defaced the property of Elbit, the British-based arms company, profiteering from the bloodshed in Gaza.

Political interference in jury trials

On 20 December 2023, with public attention elsewhere, Prentice asked the Court of Appeal to consider removing this defence, citing high numbers of recent acquittals in criminal damage cases.

Just a few months previously, the Guardian reported:

Israeli embassy officials in London attempted to get the attorney general’s office to intervene in UK court cases relating to the prosecution of protesters, documents seen by the Guardian suggest.

Defendants prevented from explaining their actions in court

As a result, more and more people taking nonviolent direct action as a matter of conscience could find themselves in court with no legal defence and effectively banned from explaining their motivations to the jury.

Extinction Rebellion co-founder Dr Gail Bradbrook has already been denied the use of this defence and was therefore left without any legal defence in her trial last November for breaking a window at the Department for Transport. Others have been imprisoned just for using the words ‘climate change’ and ‘fuel poverty’ in court.

This situation, in which peaceful activists are left silenced and defenceless in court, has been described by UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders, Michel Forst as “extremely concerning”.

Last month, in a report commissioned and released by the UN, he noted that:

It is very difficult to understand what could justify denying the jury the opportunity to hear the reason for the defendant’s action, and how a jury could reach a properly informed decision without hearing it, in particular at the time of environmental defenders’ peaceful but ever more urgent calls for the government to take pressing action for the climate.

When is a ruling expected?

Time and time again, when people have been to explain their motivations to a jury of their peers, and to communicate the evidence that direct action is effective in bringing about political change, juries find them not-guilty.

The Attorney General is attempting to end the pattern, even if it means compromise to fundamental legal principles, such as the right of a defendant to a serious criminal charge to explain their action to a jury of their peers.

The hearing of the Attorney General’s application will be completed on 21 February. Although the hearing may give a good indication of the Court’s position, it is common for the Court of Appeal to reserve judgement (ie to issue their ruling at a later date).

Crowds to gather for three momentous hearings

On the same day, two other momentous cases will also be heard at the Royal Courts of Justice.

The final appeal of Julian Assange against extradition to the US; and the legal challenge to the Government’s ‘net zero strategy’ brought by the Good Law Project and Friends of the Earth.

Crowds will gather at 9am on 21 February outside the court to hear from a number of expert witnesses concerning the implications of the Attorney General’s application, including a number of those who have been acquitted on the basis of the defence of consent.

Featured image via Defend Our Juries

Why even Julian Assange’s critics should defend him

Thomas Fazi

FEBRUARY 20, 2024

Britain’s political class rightly responded to the mysterious death of Alexei Navalny with an assortment of horror, outrage and indignation. The Kremlin critic’s treatment was an “appalling human rights outrage”, foreign secretary Lord Cameron said. Putin has to be “held to account”, Labour leader Keir Starmer added. So, when Julian Assange arrives at the High Court today for his final hearing, after being held without trial in Belmarsh maximum-security prison for almost five years, will the country’s political elite once again proclaim their commitment to human rights? I suspect not.

If the court rules out a further appeal, the Australian founder of WikiLeaks could be immediately extradited to the United States, where he will almost certainly be incarcerated for the rest of his life on charges of espionage — most likely in extremely punitive conditions. “If he’s extradited, he will die,” his wife Stella has said.

The British Government’s lack of concern for Assange’s fate is not surprising: they are the ones that put him in prison in the first place, after all. More worrying is the fact that much of the public also seems relatively unconcerned. This is probably the result of a campaign waged against Assange over the past decade and a half, aimed at destroying his reputation and depriving him of public support. Those not privy to the case’s details may even think that Assange is in jail because he’s been convicted for one of the many crimes he’s been accused of over the years — from rape to cyber-crime to espionage.

Yet this would be a gross misreading. Since 2019, Assange has been imprisoned in Belmarsh — and subjected to “prolonged psychological torture”, according to a UN report — despite being technically innocent before British law, since he’s never been convicted of any crime except violating his bail order when, 12 years ago, he sought political asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy, a crime that carries a maximum sentence of 12 months.

Assange’s ordeal began in August 2010, when he was investigated in Sweden for rape and sexual molestation. Four months later, the Swedish authorities ordered his arrest. Many viewed the timing as deeply suspicious: that year, WikiLeaks’ series of exposes had rattled Western governments and dominated front pages.

By releasing hundreds of thousands of confidential Pentagon, CIA and NSA files, the organisation had exposed civilian massacres in Iraq and Afghanistan, torture, illegal “renditions”, mass surveillance programmes, political scandals, pressure on foreign governments and widespread corruption. Assange took on the ultimate level of power — that which operates behind our societies’ official democratic façade, where state bureaucracies, military-security apparatuses and all-powerful financial-corporate enterprises collude in the shadows. The Italian investigative journalist Stefania Maurizi, who has collaborated with WikiLeaks for several years, coined the term “secret power” to describe this reality, over which citizens have no control, and often don’t even know exists.

Until WikiLeaks came along, this secret power had been largely shielded from public scrutiny, except for rare occasions, and thus allowed to operate with impunity. “For the first time in history, WikiLeaks ripped a gaping hole in this secret power,” Maurizi wrote. Today, many of us are aware of the way in which the national-security complex operates in lockstep with Big Tech and the media to censor dissenting voices. But Assange was warning us about it more than a decade ago. No wonder the system came down on him so hard.

Was there any basis to the accusations that kickstarted 14 years of “lawfare” against Assange? Several years after the Swedish authorities opened the investigation, it emerged that neither of the two alleged victims had wanted to press charges against Assange — let alone accuse him of rape. As Nils Melzer, former United National Special Rapporteur on Torture, wrote in a scathing report on the Assange case, there are “strong indications that the Swedish police and prosecution deliberately manipulated and pressured [at least one of the alleged victims], who had come to the police station for an entirely different purpose, into making a statement which could be used to arrest Mr Assange on the suspicion of rape”.

One of the many myths surrounding the case is that it never went to trial because Assange evaded justice. In reality, Assange, who was then in the UK, made himself available for questioning via several means, by telephone or video conference, or in person in the Australian embassy. But the Swedish authorities insisted on questioning him in Sweden. Assange’s legal team countered that extradition of a suspect simply to question him — not to send him to trial, as he had not been charged — was a disproportionate measure.

This was more than a technicality: Assange feared that if he were extradited to Sweden, the latter’s authorities would extradite him to the US, where he had good reason to believe he wouldn’t be given a fair trial. Sweden, after all, always refused to provide Assange a guarantee of non-extradition to the US — the reason why, when in 2012 the British Supreme Court ruled that he should be extradited to Sweden, Assange sought political asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy. From there, however, he continued to make known his availability to be interrogated by the Swedish authorities inside the embassy, but they never replied.

And thanks to a FOIA investigation by Maurizi, we now know the reason. During this period, the UK Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), then led by one Keir Starmer, played a crucial role in getting Sweden to pursue this highly unusual line of conduct. In early 2011, while Assange was still under house arrest, Paul Close, a British lawyer with the CPS, gave his Swedish counterparts his opinion on the case, apparently not for the first time. “My earlier advice remains, that in my view it would not be prudent for the Swedish authorities to try to interview the defendant in the UK,” he wrote. Why did the CPS advise the Swedes against the only legal strategy that could have brought the case to a rapid resolution, namely questioning Julian Assange in London, rather than insisting on his extradition?

In hindsight, the motivation behind this was more than murky: it appears to have been a matter of keeping the case in legal limbo, and Assange trapped in Britain for as long as possible. A year after Assange sought refuge in the embassy, the Swedish prosecutor was considering dropping the extradition proceedings, but was deterred from doing so by the CPS. She was concerned, among other things, about the mounting costs of the British police force guarding the embassy day and night. But for the British authorities this was not a problem; they replied that they “do not consider costs are a relevant factor in this matter”.

Meanwhile, it took the Swedish prosecutor five years to finally agree to question Assange in London — but only because the statute of limitations for two of the allegations was about to expire. However, deliberately or out of sheer incompetence, the request was sent too late for the Ecuadorian authorities to process it in time. The case relating to the two allegations thus expired.

The case regarding the third allegation, minor rape, was also closed two years later — thus ensuring that the two alleged victims would never receive any closure, and the accusations would stick to Julian forever. At this point, there was no arrest warrant hanging over Assange’s head anymore, but he remained in the embassy because if he had stepped off the premises, he would have been immediately arrested by the British police for violating his bail order (and, he feared, extradited to the US).

As a result of the Swedish authorities’ highly unusual behaviour, Assange had by then been arbitrarily and illegitimately forced into detention for seven years, as was concluded even by the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. Melzer, the former UN Rapporteur, would later list 50 perceived due-process violations by the Swedish authorities, including “proactive manipulation of evidence”, such as replacing the content of the women’s statement unbeknown to the latter. “[T]he Swedish authorities did everything to prevent a proper investigation and judicial resolution of their rape allegations against Assange,” Melzer concluded.

It seems, then, that the Swedish “investigation” was never about bringing justice to the alleged victims or establishing the truth; it was a way of destroying Assange by setting in motion the legal machinery that has been crushing him ever since — and of course sullying his reputation by associating his name, in the public sphere, with rape.

“The Swedish “investigation” was never about bringing justice to the alleged victims.”

What role, if any, did Starmer play in all this? During the period when the CPS was overseeing Assange’s extradition to Sweden, Starmer made several trips to Washington as Director of Public Prosecutions. US records show Starmer met with Attorney General Eric Holder and a host of American and British national security officials. Using the FOIA, the British media organisation Declassified requested the itinerary for each of Starmer’s four trips to Washington with details of his official meetings, including any briefing notes. CPS replied that all the documents relative to Starmer’s trips to Washington had been destroyed. Asked for clarification, and whether the destruction of documents was routine, the CPS did not respond.

Similarly, when Maurizi submitted a FOIA request to the CPS to shed light on the correspondence between Close and the Swedish authorities, she was also told that all the data associated with Close’s account had been deleted when he retired and could not be recovered. The CPS added that the Close’s email account had been deleted “in accordance with standard procedure”, though Maurizi would later discover that this procedure was by no means standard. Since then, Maurizi has been waging a years-long legal fight to access documents related to the CPS and Assange case, but she has been systematically stonewalled by CPS — even though a judge ordered the CPS to come clean about the destruction of key documents on Assange.

Assange’s worst fears came true when, in 2019, the British authorities finally arrested him, after reaching a deal with the new pro-US Ecuadorian government. Following his arrest, the US immediately announced that it was charging Assange for computer fraud — to which they added 17 much more serious counts of alleged violations of the Espionage Act — and requested his extradition. This was the first time, in the 102 years since the draconian law’s enactment, that a journalist was charged under the Espionage Act, which makes no distinction between a spy working for a foreign government and a journalist like Assange.

The WikiLeaks founder has been fighting his extradition to the US ever since, against a British judiciary system apparently intent on punishing Assange, even disregarding fundamental principles of due process. Melzer has described the proceedings as “a show trial more redolent of an authoritarian regime than a mature democracy… whose sole purpose is to silence Assange and to intimidate journalists and the broader public worldwide”.

Paradoxically, however, this simply confirms what WikiLeaks’ had already exposed: that nominally democratic states are willing to bend and even break the law to silence those who threaten the status quo, including journalists.

This is why, even if you disagree with Assange’s methods or political ideas, this case should matter. For it is about so much more than one man: it is about whether you want to live in a society where journalists can expose the crimes of the powerful without the fear of being persecuted and imprisoned. If the British state allows Assange to be extradited to the US, it won’t just be dealing a potentially deadly blow just to one man, but to the rule of law itself.

Thomas Fazi is an UnHerd columnist and translator. His latest book is THE COVID CONSENSUS, co-authored with Toby Green.

Julian Assange’s Final Appeal

Julian Assange will make his final appeal this week to the British courts to avoid extradition. If he is extradited it is the death of investigations into the inner workings of power by the press.

Image by Duncan Cumming via Flickr

If Julian Assange is denied permission to appeal his extradition to the United States before a panel of two judges at the High Court in London this week, he will have no recourse left within the British legal system. His lawyers can ask the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for a stay of execution under Rule 39, which is given in “exceptional circumstances” and “only where there is an imminent risk of irreparable harm.” But it is far from certain that the British court will agree. It may order Julian’s immediate extradition prior to a Rule 39 instruction or may decide to ignore a request from the ECtHR to allow Julian to have his case heard by the court.

The nearly 15-year-long persecution of Julian, which has taken a heavy toll on his physical and psychological health, is done in the name of extradition to the U.S. where he would stand trial for allegedly violating 17 counts of the 1917 Espionage Act, with a potential sentence of 170 years.

Julian’s “crime” is that he published classified documents, internal messages, reports and videos from the U.S. government and U.S. military in 2010, which were provided by U.S. army whistleblower Chelsea Manning. This vast trove of material revealed massacres of civilians, torture, assassinations, the list of detainees held at Guantanamo Bay and the conditions they were subjected to, as well as the Rules of Engagement in Iraq. Those who perpetrated these crimes — including the U.S. helicopter pilots who gunned down two Reuters journalists and 10 other civilians and severely injured two children, all captured in the Collateral Murder video — have never been prosecuted.

Julian exposed what the U.S. empire seeks to airbrush out of history.

Julian’s persecution is an ominous message to the rest of us. Defy the U.S. imperium, expose its crimes, and no matter who you are, no matter what country you come from, no matter where you live, you will be hunted down and brought to the U.S. to spend the rest of your life in one of the harshest prison systems on earth. If Julian is found guilty it will mean the death of investigative journalism into the inner workings of state power. To possess, much less publish, classified material — as I did when I was a reporter for The New York Times — will be criminalized. And that is the point, one understood by The New York Times, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, El País and The Guardian, who issued a joint letter calling on the U.S. to drop the charges against him.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and other federal lawmakers voted on Thursday for the United States and Britain to end Julian’s incarceration, noting that it stemmed from him “doing his job as a journalist” to reveal “evidence of misconduct by the U.S.”

The legal case against Julian, which I have covered from the beginning and will cover again in London this week, has a bizarre Alice-in-Wonderland quality, where judges and lawyers speak in solemn tones about law and justice while making a mockery of the most basic tenants of civil liberties and jurisprudence.

How can hearings go forward when the Spanish security firm at the Ecuadorian Embassy, UC Global, where Julian sought refuge for seven years, provided videotaped surveillance of meetings between Julian and his lawyers to the CIA, eviscerating attorney-client privilege? This alone should have seen the case thrown out of court.

How can the Ecuadorian government led by Lenin Moreno violate international law by rescinding Julian’s asylum status and permit London Metropolitan Police into the Ecuadorian Embassy — sovereign territory of Ecuador — to carry Julian to a waiting police van?

Why did the courts accept the prosecution’s charge that Julian is not a legitimate journalist?

Why did the United States and Britain ignore Article 4 of their Extradition Treaty that prohibits extradition for political offenses?

How is the case against Julian allowed to go ahead after the key witness for the United States, Sigurdur Thordarson – a convicted fraudster and pedophile – admitted to fabricating the accusations he made against Julian?

How can Julian, an Australian citizen, be charged under the U.S. Espionage Act when he did not engage in espionage and wasn’t based in the U.S when he received the leaked documents?

Why are the British courts permitting Julian to be extradited to the U.S. when the CIA — in addition to putting Julian under 24-hour video and digital surveillance while in the Ecuadorian Embassy — considered kidnapping and assassinating him, plans that included a potential shoot-out on the streets of London with involvement by the Metropolitan Police?

How can Julian be condemned as a publisher when he did not, as Daniel Ellsberg did, obtain and leak the classified documents he published?

Why is the U.S. government not charging the publisher of The New York Times or The Guardian with espionage for publishing the same leaked material in partnership with WikiLeaks?

Why is Julian being held in isolation in a high-security prison without trial for nearly five years when his only technical violation of the law is breaching bail conditions when he sought asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy? Normally this would entail a fine.

Why was he denied bail after he was sent to HM Prison Belmarsh?

If Julian is extradited, his judicial lynching will get worse. His defense will be stymied by U.S. anti-terrorism laws, including the Espionage Act and Special Administrative Measures (SAMs). He will continue being blocked from speaking to the public — except on a rare occasion — and being released on bail. He will be tried in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia where most espionage cases have been won by the U.S. government. That the jury pool is largely drawn from those who work for or have friends and relatives who work for the CIA, and other national security agencies that are headquartered not far from the court, no doubt contributes to this string of court decisions.

The British courts, from the inception, have made the case notoriously difficult to cover, severely limiting seats in the courtroom, providing video links that have been faulty, and in the case of the hearing this week, prohibiting anyone outside of England and Wales, including journalists who had previously covered the hearings, from accessing a link to what are supposed to be public proceedings.

As usual, we are not informed about schedules or timetables. Will the court render a decision at the end of the two-day hearing on Feb. 20 and Feb. 21? Or will it wait weeks, even months, to render a ruling as it has previously? Will it permit the ECtHR to hear the case or immediately railroad Julian to the U.S.? I have my doubts about the High Court passing the case to the ECtHR, given that the parliamentary arm of the Council of Europe, which created the ECtHR, along with their Commissioner for Human Rights, oppose Julian’s “detention, extradition and prosecution” because it represents “a dangerous precedent for journalists.” Will the court honor Julian’s request to be present in the hearing, or will he be forced to remain in the high-security HM Prison Belmarsh in Thamesmead, south east London, as has also happened before? No one is able to tell us.

Julian was saved from extradition in January 2021 when District Judge Vanessa Baraitser at Westminster Magistrates’ Court refused to authorize the extradition request. In her 132-page ruling, she found that there was a “substantial risk” Julian would commit suicide due to the severity of the conditions he would endure in the U.S. prison system. But this was a slim thread. The judge accepted all the charges leveled by the U.S. against Julian as being filed in good faith. She rejected the arguments that his case was politically motivated, that he would not get a fair trial in the U.S. and that his prosecution is an assault on the freedom of the press.

Baraitser’s decision was overturned after the U.S. government appealed to the High Court in London. Although the High Court accepted Baraitser’s conclusions about Julian’s “substantial risk” of suicide if he was subjected to certain conditions within a U.S. prison, it also accepted four assurances in U.S. Diplomatic Note no. 74, given to the court in February 2021, which promised Julian would be treated well.

The U.S. government claimed in the diplomatic note that its assurances “entirely answer the concerns which caused the judge [in the lower court] to discharge Mr. Assange.” The “assurances” state that Julian will not be subject to SAMs. They promise that Julian, an Australian citizen, can serve his sentence in Australia if the Australian government requests his extradition. They promise he will receive adequate clinical and psychological care. They promise that, pre-trial and post-trial, Julian will not be held in the Administrative Maximum Facility (ADX) in Florence, Colorado.

It sounds reassuring. But it is part of the cynical judicial pantomime that characterizes Julian’s persecution.

No one is held pre-trial in ADX Florence. ADX Florence is also not the only supermax prison in the U.S. where Julian can be imprisoned. He could be placed in one of our other Guantanamo-like facilities in a Communications Management Unit (CMU). CMUs are highly restrictive units that replicate the near total isolation imposed by SAMs. The “assurances” are not legally binding. All come with escape clauses.

Should Julian do “something subsequent to the offering of these assurances that meets the tests for the imposition of SAMs or designation to ADX” he will, the court conceded, be subject to these harsher forms of control. If Australia does not request a transfer it “cannot be a cause for criticism of the USA, or a reason for regarding the assurances as inadequate to meet the judge’s concerns,” the ruling reads. And even if that were not the case, it would take Julian 10 to 15 years to appeal his sentence up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which would be more than enough time to destroy him psychologically and physically. Amnesty International said the “assurances are not worth the paper they are written on.”

Julian’s lawyers will attempt to convince two High Court judges to grant him permission to appeal a number of the arguments against extradition which Judge Baraitser dismissed in January 2021. His lawyers, if the appeal is granted, will argue that prosecuting Julian for his journalistic activity represents a “grave violation” of his right to free speech; that Julian is being prosecuted for his political opinions, something which the U.K.-U.S. extradition treaty does not allow; that Julian is charged with “pure political offenses” and the U.K.-U.S. extradition treaty prohibits extradition under such circumstances; that Julian should not be extradited to face prosecution where the Espionage Act “is being extended in an unprecedented and unforeseeable way”; that the charges could be amended resulting in Julian facing the death penalty; and that Julian will not receive a fair trial in the U.S. They are also asking for the right to introduce new evidence about CIA plans to kidnap and assassinate Julian.

If the High Court grants Julian permission to appeal, a further hearing will be scheduled during which time he will argue his appeal grounds. If the High Court refuses to grant Julian permission to appeal, the only option left is to appeal to the ECtHR. If he is unable to take his case to the ECtHR he will be extradiated to the U.S.

The decision to seek Julian’s extradition, contemplated by Barack Obama’s administration, was pursued by Donald Trump’s administration following WikiLeaks’ publication of the documents known as Vault 7, which exposed the CIA’s cyberwarfare programs, including those designed to monitor and take control of cars, smart TVs, web browsers and the operating systems of most smart phones.

The Democratic Party leadership became as bloodthirsty as the Republicans following WikiLeaks’ publishing of tens of thousands of emails belonging to the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and senior Democratic officials, including those of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman during the 2016 presidential election.

The Podesta emails exposed that Clinton and other members of Obama’s administration knew that Saudi Arabia and Qatar — which had both donated millions of dollars to the Clinton Foundation — were major funders of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. They revealed transcripts of three private talks Clinton gave to Goldman Sachs — for which she was paid $675,000 — a sum so large it can only be considered a bribe. Clinton was seen in the emails telling the financial elites that she wanted “open trade and open borders” and believed Wall Street executives were best positioned to manage the economy, a statement that contradicted her campaign promises of financial reform. They exposed the Clinton campaign’s self-described “Pied Piper” strategy which used their press contacts to influence Republican primaries by “elevating” what they called “more extreme candidates,” to ensure Trump or Ted Cruz won their party’s nomination. They exposed Clinton’s advance knowledge of questions in a primary debate. The emails also exposed Clinton as one of the architects of the war and destruction of Libya, a war she believed would burnish her credentials as a presidential candidate.

Journalists can argue that this information, like the war logs, should have remained secret. But if they do, they can’t call themselves journalists.

The Democratic leadership, which attempted to blame Russia for its election loss to Trump — in what became known as Russiagate — charged that the Podesta emails and the DNC leaks were obtained by Russian government hackers, although an investigation headed by Robert Mueller, the former FBI director, “did not develop sufficient admissible evidence that WikiLeaks knew of — or even was willfully blind to” any alleged hacking by the Russian state.

Julian is persecuted because he provided the public with the most important information about U.S. government crimes and mendacity since the release of the Pentagon Papers. Like all great journalists, he was nonpartisan. His target was power.

He made public the killing of nearly 700 civilians who had approached too closely to U.S. convoys and checkpoints, including pregnant women, the blind and deaf, and at least 30 children.

He made public the more than 15,000 unreported deaths of Iraqi civilians and the torture and abuse of some 800 men and boys, aged between 14 to 89, at Guantánamo Bay detention camp.

He showed us that Hillary Clinton in 2009 ordered U.S. diplomats to spy on U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and other U.N. representatives from China, France, Russia, and the U.K., spying that included obtaining DNA, iris scans, fingerprints, and personal passwords.

He exposed that Obama, Hillary Clinton and the CIA backed the June 2009 military coup in Honduras that overthrew the democratically-elected president Manuel Zelaya, replacing him with a murderous and corrupt military regime.

He revealed that the United States secretly launched missile, bomb and drone attacks on Yemen, killing scores of civilians.

No other contemporary journalist has come close to matching his revelations.

Julian is the first. We are next.

Related Posts

Stella Assange -- September 14, 2023

Free Julian Assange: Noam Chomsky, Dan Ellsberg & Jeremy Corbyn Lead Call at Belmarsh Tribunal

Noam Chomsky -- May 29, 2023

The Imminent Extradition of Julian Assange and the Death of Journalism

Chris Hedges -- June 19, 2023

“Free the Truth”: The Belmarsh Tribunal on Julian Assange & Defending Press Freedom

Amy Goodman -- January 01, 2024

Assange: An Unholy Masquerade of Tyranny Disguised as Justice

Craig Murray -- June 16, 2023

Chris Hedges who graduated from seminary at Harvard Divinity School, worked for nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times, National Public Radio and other news organizations in Latin America, the Middle East and the Balkans. He was part of the team of reporters at The New York Times who won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of global terrorism. Hedges is a fellow at the Nation Institute and the author of numerous books, including War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.

No comments:

Post a Comment