The Palestinian issue has never lost its resonance beyond the Middle East, especially in the Global South.

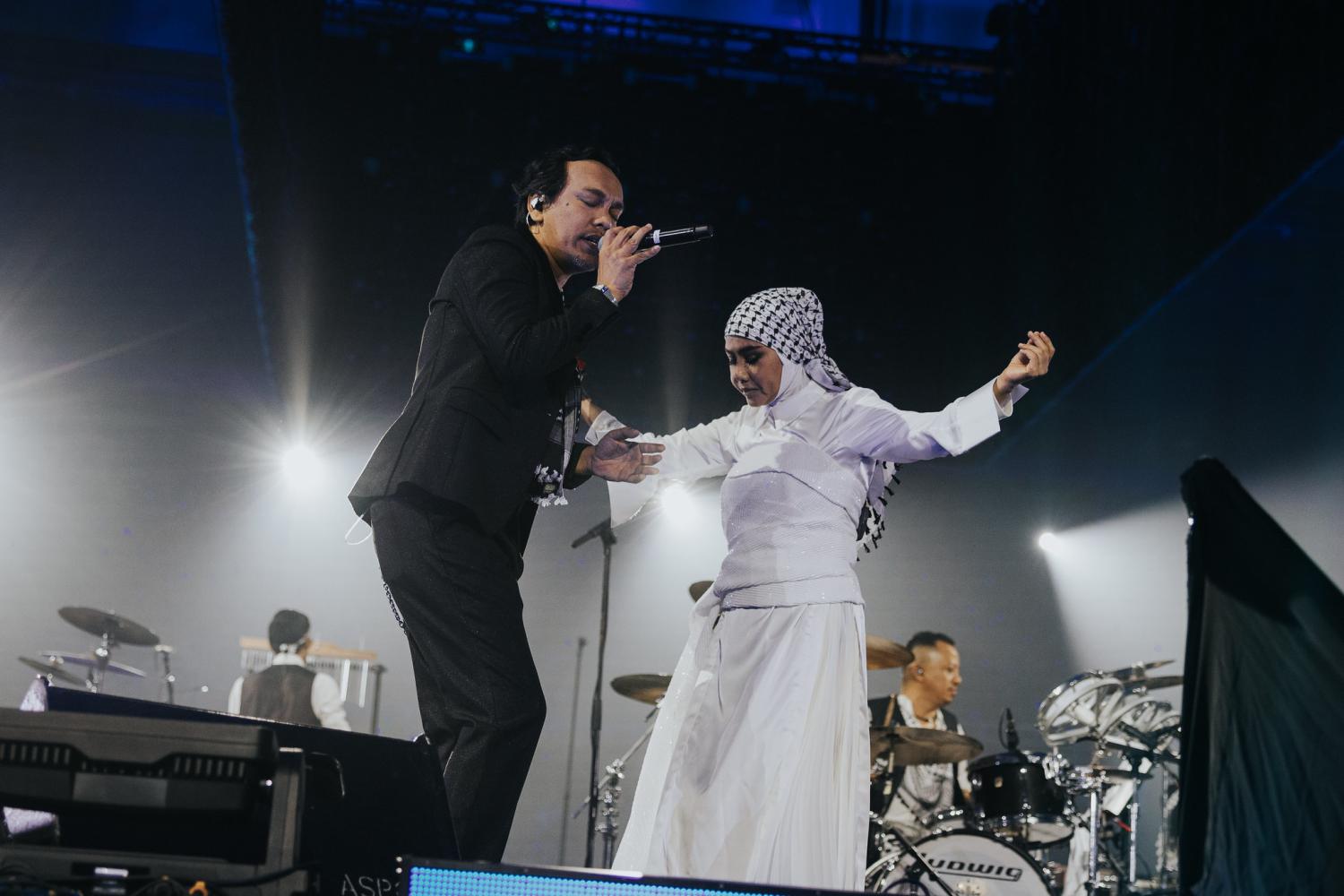

Malaysian rock star Ella, right, performs at a Gaza fundraising concert in Penang, October 2023 (Flickr/Budiey)

BEN SCOTT

Published 26 Feb 2024

The atrocities perpetrated by Hamas on 7 October 2023 and the war in Gaza that followed caught much of the world off guard. Most governments appeared surprised both by the reignition of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and its wider consequences, for regional stability and social cohesion. In a Foreign Affairs essay sent to print on 2 October, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan wrote that “although the Middle East remains beset with perennial challenges … the region is quieter than it has been for decades.”

The failure of Western capitals to appreciate the continuing global resonance of the Palestinian issue is reminiscent of earlier failures to anticipate the rise of populist politics.

Sullivan was far from alone in misjudging the region. At the root of a long list of Israeli intelligence failures in the lead-up to 7 October was an assumption that Hamas had essentially abandoned “resistance” in favour of improving conditions in, and its hold on, the Gaza Strip. To be sure, Hamas encouraged this mistake. But there were wider reasons to believe Palestinians were losing their “will to fight.”

For many decades the Palestinians were a cause célèbre for the region and the global anti-imperialist left. But when the Arab uprisings took off in early 2011, suddenly empowered Arab publics did not focus on the Palestinian cause. They devoted more attention to regional power struggles – from Libya to Yemen to Syria – than on the Palestinians, who were anyway split between the Fatah-ruled West Bank and Hamas-ruled Gaza.

As authoritarian Arab rulers reasserted themselves, they found that public animus to Israel was no longer the constraint it had once been. Regimes that had long sought covert cooperation with Israel discovered they could do so more openly and even enter formal diplomatic relations with the Jewish state. As part of the Abraham Accords, the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco did so in 2020, while paying only lip service to Palestinian interests. Until 7 October Saudi Arabia appeared set to follow suit.

But while the Palestinian issue seemed to be losing traction in the region, there was no evidence it had lost its global resonance, especially among the progressive and populist left and in the Global South. That was clear enough from the United Nations’ continued preoccupation with the issue but also evident in the boycott, divestment, sanctions movement and the strength of pro-Palestinian sentiment in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia.

At the root of a long list of Israeli intelligence failures in the lead-up to 7 October was an assumption that Hamas had essentially abandoned “resistance” in favour of improving conditions in – and its hold on – the Gaza Strip.

The failure of Western capitals to appreciate the continuing global resonance of the Palestinian issue is reminiscent of earlier failures to anticipate the rise of populist politics. In their ground-breaking book Six Faces of Globalisation, Anthea Roberts and Nicholas Lamp show how this failure flowed from inattention to the many competing narratives of globalisation, including populist narratives from the left and right. Roberts and Lamp are deliberately agnostic about the narratives they outline. They don’t want to preclude any of them. Instead, they urge policy makers to develop what Philip Tetlock terms “dragonfly eyes”:

Dragonflies have compound eyes made up of thousands of lenses that give them a range of vision of nearly 360 degrees. Dragonfly thinking involves synthesizing a multitude of points…people who integrate insights from multiple perspectives are likely to develop a more accurate understanding of complex problems than those who rely on a single perspective.

Simply insisting on the establishment narrative of globalisation (“everybody wins”) has done nothing to blunt anti-globalisation. Rather, it has blinded policy-makers to the genuine insights and animating power of alternative narratives.

It is hard to imagine a more direct assault on economic globalisation than the Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea. The Houthis purport to be fighting for the Palestinians but most experts agree they are doing it to boost their own domestic and international standing. To counter them, the US and its allies have sought to impose an “establishment narrative”: framing the issue in terms of freedom of navigation, the rules-based order and military deterrence.

Whether or not the Western framing is accurate, it has been ineffective. International support for US-led efforts to counter the Houthis has been minimal. UN voting indicates that most countries view Israel’s assault on Gaza as a more serious breach of the rules-based order than the Houthi attacks on shipping. Although China has an enormous stake in global maritime security, Beijing has found it more advantageous to blame Washington for failing to restrain Israel.

Meanwhile, the Houthis are continuing their attacks and enjoying international notoriety on a par with Hamas and Hezbollah. Palestinian supporters are willing to overlook the Houthis’ brutal and exclusionary rule in Yemen. Egypt has refused to criticise the Houthis even though the attacks are depriving Cairo of desperately needed Suez Canal revenue. Throughout the region, Sunni Arabs are downplaying sectarian divisions as they back Iran’s predominantly Shia “axis of resistance”.

Viewing the Houthi threat through dragonfly eyes would yield a better understanding of why the Houthis have sought – and apparently benefitted from – confrontation with the US. It would take account of the struggle for power within Yemen, the Houthi's role in Iran’s axis of resistance, and their use of the Palestinian narrative.

The Israel-Hamas conflict reverberates globally more than any comparable conflict, largely because both the Israelis and Palestinians have powerful and polarising narratives of righteous victimhood. Reconciling those narratives is almost certainly impossible. But, using dragonfly thinking, it should be possible to produce a wider international consensus on the outlines of a two-state solution.

No comments:

Post a Comment