Radical reform is needed to make European agriculture economically sustainable and environmentally resilient.Yet Europe’s biggest farming lobby, Copa-Cogeca, opposes any policy inimical to the interests of large landowners. In the run-up to the European elections and in the face of demonstrations by the sector across Europe, there is one constituency that conservative politicians are particularly keen to court: farmers.

Published on 13 February 2024

Thin Lei Win - Green European Journal (Brussels) - Eurozine (Vienna)

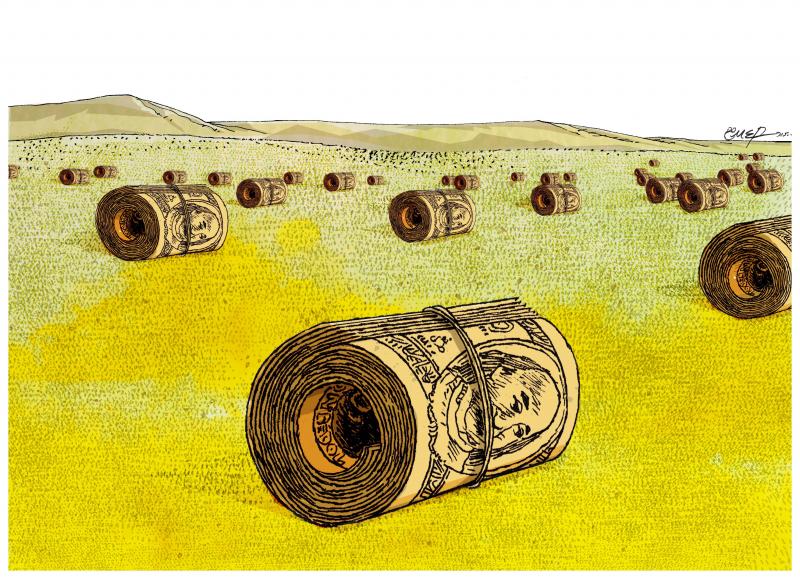

Ömer Çam | Cartoon movement

When the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), the largest group in the European Parliament, tried – and narrowly failed – to quash the Nature Restoration Law, it cited farmers and food security as reasons for its opposition. In her State of the Union speech in September, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen ‒ herself a member of the EPP ‒ made it a point to show her appreciation for farmers but avoided mentioning the Farm to Fork strategy (F2F), the Commission’s flagship effort to make agriculture fairer and more sustainable. The EPP is pitching itself as the farmers’ party and looks set to challenge and object to any attempts to rein in farming’s adverse impacts on ecosystems.

Of the more than 400 million eligible voters in the EU, only about nine million, or around 2%, work in agriculture. But politicians see their vote as crucial. This is partly because farmers are extremely vocal, but also because of a Europe-wide positive image of farmers as guardians of rural traditions and cultural heritage, and providers of our daily sustenance. This means a much wider part of the electorate sympathises and identifies with them, making them a powerful constituency.

More : Agro-industrial oligarchy and sustainable agriculture: the European farmer protests

There is no question that farmers need to be supported. Their existence is critical to Europe’s long-term food security and, ultimately, prosperity. But unfortunately, European farming is in dire straits. Despite agriculture being the EU’s largest budget item, disbursing tens of billions of public money a year, the bloc has lost three million farms over the past decade. That is a rate of 800 farmers leaving the profession every single day. Yet more concerning, they’re not being replaced: the average age of a European farmer is now 57.

These statistics date back to the decade from 2010 to 2020, before the war on Europe’s doorstep between two agricultural superpowers put further pressure on food producers, who have since struggled with rapidly rising prices of inputs such as feed, fertiliser, and pesticides. Over the past two years, European farmers have also been hit hard by multiple extreme weather events, from droughts and heatwaves to floods and wildfires, which have damaged farms and decimated harvests.

To make matters worse, scientists have warned unequivocally that extreme weather is likely to worsen and will threaten food production. It is imperative that farming not only mitigate its contribution to climate change, scientists warn, but also adapt and become resilient to these disasters, as well as to the more subtle shifts in cropping and rainfall patterns. Yet the farming lobby and the politicians who purport to care for the continued viability of European agriculture seem intent on resisting any reforms or changes to the status quo.

Misleading claims

This may be partly explained by the dominance of Copa-Cogeca, Europe’s oldest, biggest, and most powerful farming lobby. The organisation was established in 1959 at the inception of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which was itself founded on the post-war ideal that Europe should never go hungry again. Starting out as separate movements representing farming (Copa) and cooperatives (Cogeca), the two merged in the early 1960s. Its members include many of the EU’s major national farm unions, and over the years Copa-Cogeca has proclaimed itself the voice of European farmers and agricultural cooperatives in Brussels.

Copa-Cogeca claims to represent more than 22 million farmers and their families which ‒ according to European Commission data ‒ would mean the entirety of Europe’s farm sector. Yet the claim appears more aspirational than realistic, as myself and other journalists revealed in our months-long investigation with Lighthouse Reports, a non-profit investigative news outlet.

Interviews with nearly 120 farmers, insiders, politicians, academics, and activists, as well as a survey of 50 Copa-Cogeca affiliates, cast serious doubt on the lobby’s membership claims and its legitimacy in the farming community.

‘Industrial farming is a big part of the problem for most of the ecological issues that we face. We need to change the way we farm‘ – Jean Mathieu Thevenot, French Farmer

In Romania, which has Europe’s largest number of agricultural holdings at almost 2.9 million, a total of 3,500 farmers are represented by an alliance of four unions that are members of Copa-Cogeca, according to their own press releases and interviews. In Poland, around 1.3 million farmers are nominally members of Copa-Cogeca’s affiliate KRIR, which receives considerable sums of taxpayer money, but does not keep track of who it represents. The country’s Supreme Audit Office concluded in 2021 that, “due to the lack of records, agricultural chambers had no knowledge of all the members whose interests they are supposed to represent”.

In Denmark, the sole member of Copa-Cogeca is the Danish Food and Agricultural Council (L&F in Danish). Its annual reports in 2016 and 2021 showed a surge in membership of 5,000 farmers, a curious development that seems to go against both European and national statistics. The union declined to provide a full explanation for its growing membership, but its latest annual report dropped this number entirely. Spain probably has the most comprehensive dataset among the countries that were investigated. Even there, the three farm unions that are members of Copa-Cogeca together represent only 40% of the country’s farmers.

Power without representation

The long-held perception of Copa-Cogeca as the arbiter of what European farmers need and want is based on data that is unreliable, unsubstantiated, and opaque. In addition, small farmers do not feel represented. “The decisions go through the big countries, big farmers, big unions… [There’s] no equality,” said Arūnas Svitojus, president of the Lithuanian Union and Copa member LR ZUR.

Other current and former members and insiders also said Copa-Cogeca represents mostly the interests of big, industrial farmers and cooperatives and not the small- and medium-sized farmers that make up the bulk of European agriculture. According to Eurostat, of the EU’s 9.1 million agricultural holdings in 2020, 63.8% had less than five hectares and at least 75% had less than 10 hectares. Despite this, Copa-Cogeca continues to enjoy a cosy relationship with the three EU institutions at the heart of agricultural policy-making: the Commission, the Parliament, and the Council. In a 2019 article on farm subsidies, the New York Times said European leaders have historically treated Copa-Cogeca “not as mere recipients of government money, but as partners in policymaking.”

Copa-Cogeca is the only group invited to meet and talk to the president of the Council before every meeting of EU agricultural ministers. Copa-Cogeca also had the largest number of seats on civil dialogue groups that assist and advise the Commission. The structure of these groups has recently been reformed, but sources say that Copa-Cogeca continues to dominate discussions. Commission insiders also spoke of “a mutual understanding” between DG AGRI, the branch of the Commission responsible for agricultural policy, and Copa-Cogeca.

In emails to members of the EU Parliament, Lighthouse Reports found, the lobby group gives detailed suggestions on how to vote on a certain piece of legislation and what kind of amendments should be made. One MEP has even felt Copa-Cogeca’s correspondence was a veiled threat.

This chummy, closed-loop relationship between the legislative, the executive, and interest groups in Brussels that have a tight grip on agricultural policy-making has been dubbed “The Iron Triangle”. Power without representation can lead to policies skewed to benefit the few that wander the corridors of power in Brussels, rather than the millions of farmers toiling away in the fields.

In the past year (2023), Copa-Cogeca has used its position to oppose environmental reforms proposed by the Green Deal and Farm to Fork Strategy, including successfully sabotaging a law to cut pesticide use, defeating efforts to require large-scale farm operations to reduce harmful emissions, and attempting to derail a law that would restore European ecosystems. Its lobbying also delayed crop rotation and fallow land requirements under the CAP. In addition, it is against linking farm subsidies to environmental outcomes. Crucially, it does not want to put a ceiling on the maximum amount of money a farm can get under the CAP, which has so far benefited large landowners at the expense of small- and medium-sized farmers.

Disenfranchised farmers

This has the effect of disenfranchising the kind of young and committed farmers that Europe desperately needs, and perpetuating the vicious cycle of more farmers abandoning agriculture than can be replaced. Like Tijs Boelens, a former activist and social worker who now grows organic vegetables and indigenous wheat and barley varieties in Flanders. “We are not at all seen. We don’t count because we don’t have money,” he told me over a Zoom call during an afternoon break. His anger at policies at regional, national, and European Union levels ‒ which he said are very much focused on large-scale, industrial, intensive farming ‒ is palpable.

Like Katja Temnik, a former basketball star-turned-herbalist and biodynamic farmer, who during the annual EU conference on the future of agriculture in Brussels warned the assembled parliamentarians, bureaucrats, lobbyists, and farmers that the increasing emphasis on technology-driven food production was wrong. Temnik said that decision makers “are completely isolated from reality or what people who actually live and work with land need and feel.”

Like David Peacock, founder of the lauded Erdhof Seewalde, a 111-hectare mixed livestock farm in northern Germany, who feels disconnected from big farm unions like Copa-Cogeca because “the way they farm and what they’re doing is destroying the planet.” He adds, “I know it is possible to work differently. So I’m quite critical of what they’re doing and of the structures behind the whole thing.”

More : Green populism: How the far-right embraces ecology

Like Jean Mathieu Thevenot and his friend, young engineers who have set up a farm in the French Basque country as “a political choice” to say “industrial farming is a big part of the problem for most of the ecological issues that we face. We need to change the way we farm.” “Most of the youth farmers I know and work with,” adds Thevenot, “are disconnected and in complete disagreement with the vision of Copa-Cogeca, which has a lot of power in the EU but advocates in favour of the status quo and industrial agriculture.”

Like Bogdan Suliman, a Romanian former utility worker who turned to farming to support his parents and is charting a very different path from his older neighbours who advised him to use as much fertilisers and pesticides as possible. He is trying to recreate a sustainable ecosystem that does not require chemicals to control pests or boost productivity. “We need a different mentality,” he says.

Although not all farmers are eager to change their practices, many are ‒ especially if it allows them to make a reasonable profit. Research shows this is a realistic perspective. If Farm to Fork is implemented carefully, many farmers stand to gain and only some will lose out. But this requires a bold set of measures and courageous, forward-looking representatives of European farmers.

This is why Copa-Cogeca’s lack of representation and the EPP positioning itself as a “farmers’ party” are so concerning. If these two largest and most powerful groups in Brussels continue to resist any reforms to how we produce, consume, and discard food, they will be doing a disservice both to the farmers who want to change and the consumers who need healthy and affordable food that does not wreck the planet. Ultimately, this will undermine European agriculture and the continent’s ability to feed its people.

When the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), the largest group in the European Parliament, tried – and narrowly failed – to quash the Nature Restoration Law, it cited farmers and food security as reasons for its opposition. In her State of the Union speech in September, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen ‒ herself a member of the EPP ‒ made it a point to show her appreciation for farmers but avoided mentioning the Farm to Fork strategy (F2F), the Commission’s flagship effort to make agriculture fairer and more sustainable. The EPP is pitching itself as the farmers’ party and looks set to challenge and object to any attempts to rein in farming’s adverse impacts on ecosystems.

Of the more than 400 million eligible voters in the EU, only about nine million, or around 2%, work in agriculture. But politicians see their vote as crucial. This is partly because farmers are extremely vocal, but also because of a Europe-wide positive image of farmers as guardians of rural traditions and cultural heritage, and providers of our daily sustenance. This means a much wider part of the electorate sympathises and identifies with them, making them a powerful constituency.

More : Agro-industrial oligarchy and sustainable agriculture: the European farmer protests

There is no question that farmers need to be supported. Their existence is critical to Europe’s long-term food security and, ultimately, prosperity. But unfortunately, European farming is in dire straits. Despite agriculture being the EU’s largest budget item, disbursing tens of billions of public money a year, the bloc has lost three million farms over the past decade. That is a rate of 800 farmers leaving the profession every single day. Yet more concerning, they’re not being replaced: the average age of a European farmer is now 57.

These statistics date back to the decade from 2010 to 2020, before the war on Europe’s doorstep between two agricultural superpowers put further pressure on food producers, who have since struggled with rapidly rising prices of inputs such as feed, fertiliser, and pesticides. Over the past two years, European farmers have also been hit hard by multiple extreme weather events, from droughts and heatwaves to floods and wildfires, which have damaged farms and decimated harvests.

To make matters worse, scientists have warned unequivocally that extreme weather is likely to worsen and will threaten food production. It is imperative that farming not only mitigate its contribution to climate change, scientists warn, but also adapt and become resilient to these disasters, as well as to the more subtle shifts in cropping and rainfall patterns. Yet the farming lobby and the politicians who purport to care for the continued viability of European agriculture seem intent on resisting any reforms or changes to the status quo.

Misleading claims

This may be partly explained by the dominance of Copa-Cogeca, Europe’s oldest, biggest, and most powerful farming lobby. The organisation was established in 1959 at the inception of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which was itself founded on the post-war ideal that Europe should never go hungry again. Starting out as separate movements representing farming (Copa) and cooperatives (Cogeca), the two merged in the early 1960s. Its members include many of the EU’s major national farm unions, and over the years Copa-Cogeca has proclaimed itself the voice of European farmers and agricultural cooperatives in Brussels.

Copa-Cogeca claims to represent more than 22 million farmers and their families which ‒ according to European Commission data ‒ would mean the entirety of Europe’s farm sector. Yet the claim appears more aspirational than realistic, as myself and other journalists revealed in our months-long investigation with Lighthouse Reports, a non-profit investigative news outlet.

Interviews with nearly 120 farmers, insiders, politicians, academics, and activists, as well as a survey of 50 Copa-Cogeca affiliates, cast serious doubt on the lobby’s membership claims and its legitimacy in the farming community.

‘Industrial farming is a big part of the problem for most of the ecological issues that we face. We need to change the way we farm‘ – Jean Mathieu Thevenot, French Farmer

In Romania, which has Europe’s largest number of agricultural holdings at almost 2.9 million, a total of 3,500 farmers are represented by an alliance of four unions that are members of Copa-Cogeca, according to their own press releases and interviews. In Poland, around 1.3 million farmers are nominally members of Copa-Cogeca’s affiliate KRIR, which receives considerable sums of taxpayer money, but does not keep track of who it represents. The country’s Supreme Audit Office concluded in 2021 that, “due to the lack of records, agricultural chambers had no knowledge of all the members whose interests they are supposed to represent”.

In Denmark, the sole member of Copa-Cogeca is the Danish Food and Agricultural Council (L&F in Danish). Its annual reports in 2016 and 2021 showed a surge in membership of 5,000 farmers, a curious development that seems to go against both European and national statistics. The union declined to provide a full explanation for its growing membership, but its latest annual report dropped this number entirely. Spain probably has the most comprehensive dataset among the countries that were investigated. Even there, the three farm unions that are members of Copa-Cogeca together represent only 40% of the country’s farmers.

Power without representation

The long-held perception of Copa-Cogeca as the arbiter of what European farmers need and want is based on data that is unreliable, unsubstantiated, and opaque. In addition, small farmers do not feel represented. “The decisions go through the big countries, big farmers, big unions… [There’s] no equality,” said Arūnas Svitojus, president of the Lithuanian Union and Copa member LR ZUR.

Other current and former members and insiders also said Copa-Cogeca represents mostly the interests of big, industrial farmers and cooperatives and not the small- and medium-sized farmers that make up the bulk of European agriculture. According to Eurostat, of the EU’s 9.1 million agricultural holdings in 2020, 63.8% had less than five hectares and at least 75% had less than 10 hectares. Despite this, Copa-Cogeca continues to enjoy a cosy relationship with the three EU institutions at the heart of agricultural policy-making: the Commission, the Parliament, and the Council. In a 2019 article on farm subsidies, the New York Times said European leaders have historically treated Copa-Cogeca “not as mere recipients of government money, but as partners in policymaking.”

Copa-Cogeca is the only group invited to meet and talk to the president of the Council before every meeting of EU agricultural ministers. Copa-Cogeca also had the largest number of seats on civil dialogue groups that assist and advise the Commission. The structure of these groups has recently been reformed, but sources say that Copa-Cogeca continues to dominate discussions. Commission insiders also spoke of “a mutual understanding” between DG AGRI, the branch of the Commission responsible for agricultural policy, and Copa-Cogeca.

In emails to members of the EU Parliament, Lighthouse Reports found, the lobby group gives detailed suggestions on how to vote on a certain piece of legislation and what kind of amendments should be made. One MEP has even felt Copa-Cogeca’s correspondence was a veiled threat.

This chummy, closed-loop relationship between the legislative, the executive, and interest groups in Brussels that have a tight grip on agricultural policy-making has been dubbed “The Iron Triangle”. Power without representation can lead to policies skewed to benefit the few that wander the corridors of power in Brussels, rather than the millions of farmers toiling away in the fields.

In the past year (2023), Copa-Cogeca has used its position to oppose environmental reforms proposed by the Green Deal and Farm to Fork Strategy, including successfully sabotaging a law to cut pesticide use, defeating efforts to require large-scale farm operations to reduce harmful emissions, and attempting to derail a law that would restore European ecosystems. Its lobbying also delayed crop rotation and fallow land requirements under the CAP. In addition, it is against linking farm subsidies to environmental outcomes. Crucially, it does not want to put a ceiling on the maximum amount of money a farm can get under the CAP, which has so far benefited large landowners at the expense of small- and medium-sized farmers.

Disenfranchised farmers

This has the effect of disenfranchising the kind of young and committed farmers that Europe desperately needs, and perpetuating the vicious cycle of more farmers abandoning agriculture than can be replaced. Like Tijs Boelens, a former activist and social worker who now grows organic vegetables and indigenous wheat and barley varieties in Flanders. “We are not at all seen. We don’t count because we don’t have money,” he told me over a Zoom call during an afternoon break. His anger at policies at regional, national, and European Union levels ‒ which he said are very much focused on large-scale, industrial, intensive farming ‒ is palpable.

Like Katja Temnik, a former basketball star-turned-herbalist and biodynamic farmer, who during the annual EU conference on the future of agriculture in Brussels warned the assembled parliamentarians, bureaucrats, lobbyists, and farmers that the increasing emphasis on technology-driven food production was wrong. Temnik said that decision makers “are completely isolated from reality or what people who actually live and work with land need and feel.”

Like David Peacock, founder of the lauded Erdhof Seewalde, a 111-hectare mixed livestock farm in northern Germany, who feels disconnected from big farm unions like Copa-Cogeca because “the way they farm and what they’re doing is destroying the planet.” He adds, “I know it is possible to work differently. So I’m quite critical of what they’re doing and of the structures behind the whole thing.”

More : Green populism: How the far-right embraces ecology

Like Jean Mathieu Thevenot and his friend, young engineers who have set up a farm in the French Basque country as “a political choice” to say “industrial farming is a big part of the problem for most of the ecological issues that we face. We need to change the way we farm.” “Most of the youth farmers I know and work with,” adds Thevenot, “are disconnected and in complete disagreement with the vision of Copa-Cogeca, which has a lot of power in the EU but advocates in favour of the status quo and industrial agriculture.”

Like Bogdan Suliman, a Romanian former utility worker who turned to farming to support his parents and is charting a very different path from his older neighbours who advised him to use as much fertilisers and pesticides as possible. He is trying to recreate a sustainable ecosystem that does not require chemicals to control pests or boost productivity. “We need a different mentality,” he says.

Although not all farmers are eager to change their practices, many are ‒ especially if it allows them to make a reasonable profit. Research shows this is a realistic perspective. If Farm to Fork is implemented carefully, many farmers stand to gain and only some will lose out. But this requires a bold set of measures and courageous, forward-looking representatives of European farmers.

This is why Copa-Cogeca’s lack of representation and the EPP positioning itself as a “farmers’ party” are so concerning. If these two largest and most powerful groups in Brussels continue to resist any reforms to how we produce, consume, and discard food, they will be doing a disservice both to the farmers who want to change and the consumers who need healthy and affordable food that does not wreck the planet. Ultimately, this will undermine European agriculture and the continent’s ability to feed its people.

👉 Original article on Green European Journal

This article is part of the series “Breaking Bread: Food and Water Systems Under Pressure”. The project is organised by the Green European Journal with the support of Eurozine, and thanks to the financial support of the European Parliament to the Green European Foundation. The EU Parliament is not responsible for the content of this project.

Agro-industrial oligarchy and sustainable agriculture: the European farmer protests

Who are they and why are they protesting? European agriculture, an industry that involves around nine million workers, is in deep crisis, bringing thousands to the streets across Europe, with similar demands but various motivations.

Published on 8 February 2024

More : Green populism: How the far-right embraces ecology

According to 2020 data from Eurostat, there are about 8.7 million farmers in Europe, only 11.9 percent of whom are under 40 years old. This figure represents a little over 2 percent of the electorate for the upcoming European elections. Since restructuring due to the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy), the number of farms in the EU has declined by more than a third since 2005, explains Jon Henley, Europe correspondent for The Guardian.

A Politico.eu map shows where protests have taken place and (briefly) for what reasons."In 11 EU countries, producer prices [base price farmers receive for their produce] fell by more than 10 percent from 2022 to 2023.Only Greece and Cyprus have seen a corresponding increase in farmers' sales revenues, thanks to increased demand for olive oil," writes Hanne Cokelaere and Bartosz Brzeziński.

Henley In The Guardian writes that "besides feeling persecuted by what they see as a Brussels bureaucracy that knows little about their business, many farmers complain they feel caught between apparently conflicting public demands for cheap food and climate-friendly processes." For many, it is not climate compliance that is causing the agricultural world to suffer, but "competition between farmers and the concentration of farms," as Véronique Marchesseau, farmer et secretary-general of the French leftist union Confédération paysanne, explains in Alternatives Economiques. At the same time, adds Nicolas Legendre, a journalist specializing in the topic, interviewed by Vert, there is also a "visceral anger from part of the agricultural world toward environmentalists (and environmentalism in general), fueled by certain agro-industrial players."

While the press has a tendency to report on a "movement," the agricultural world is not monolithic. The mobilisation of European farmers emerges from a sector that is diverse in not only the modes of production, but also in worldview, political orientation, income level and social class.

More : Lucas Chancel: ‘Those who are most affected are those who pollute the least’

In Reporterre, a site specialising in ecology and social struggles that we often feature in Voxeurop, we learn that in France the average area of a farm is 96 hectares. Arnaud Rousseau, leader of FNSEA, the majority union of French farmers, owns a 700-hectare farm. Why would I mention Rousseau? Because, to return to the question of movements - who they represent, and who is represented - it is important to mention when a leading voice of a protest movement is that of an agribusiness oligarch. A portrait/investigation by Amélie Poinssot for Mediapart clarifies the political dimension: "He is the head of a giant of the French economy: Avril-Sofiprotéol, a giant of so-called seed oil and protein crops, founded by the trade union. It is no less than the fourth largest agribusiness group in France."

As Ingwar Perowanowitsch explains in taz, "there are powerful agricultural holding companies that receive up to 5 million euro in subsidies per year. And there are small family farms that receive a few hundred euro. There is animal husbandry and cultivation. There are conventional and organic farmers. Some produce for the world market, others for the weekly market." The German newspaper quotes a farmer from Leipzig, who works for a cooperative farm, who decided not to demonstrate in January due to the infiltration of the far right, and because he did not feel represented: "the farmers' association defends the interests of large companies that produce for the world market and not those of small-scale agriculture."

Farmers and violence: double standards

For Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, "many of the farmers' concerns are legitimate", as Le Soir reports, in the wake of demonstrations that saw thousands of farmers in Brussels light fires and throw eggs at the European Parliament building on 1 February. In El Pais Marc Bassets writes that "power fears them. The majority of the population looks at them with distance and respect."

This is an attitude that finds its peak in France, where the difference in treatment of protesters at the hands of police is flagrant. Europe has denounced the excessive violence of the police, first and foremost toward the Gilets Jaunes, but also various demonstrations around the country (against pension reforms, or during the riots in the banlieues), and finally the use of 5,000 grenades against the "ecoterrorists" in Sainte-Soline.

In recent days farmers have not only blocked roads and highways, or poured straw and manure, but also detonated a bomb in one building, and set fire to another. But no one is talking about "agroterrorism," and the police have never intervened. Quite the contrary, in fact. As for the minister of the interior, Gérard Darmanin, he abandoned his usual martial tone by expressing on TF1 his "compassion" for the farmers and stating that "you don't respond to suffering by sending CRS [riot police], voilà."

"Since World War II, public authorities have tolerated from farmers what they would not tolerate from other social groups," historian Edouard Lynch, an expert in rural studies, tells Libération. Moreover, not all farmers are equal: "Even within farmer movements, the state targets minority groups, as shown by the repression of demonstrations against the mega-basins in Sainte-Soline," in Western France, Lynch continues. On Arrêt sur Images, Lynch adds, "One can see today [in the face of these demonstrations] how the violence we have witnessed in recent years is the result of the strategies of the forces of law and order. [...] The violence of social movements is provoked by the keepers of the peace: decisions are made to move toward confrontation in order to stigmatise the opponent." Behind this, he explains, is a kind of national mythology of the "good farmer who feeds the nation."

Lynch is echoed by Thin Lei Win in Green European Journal: there is "a positive European-wide image of farmers as custodians of rural traditions and cultural heritage, as well as providers of our livelihood. This means that a much larger part of the electorate sympathises and identifies with them."

In partnership with Display Europe, cofunded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Directorate‑General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Who are they and why are they protesting? European agriculture, an industry that involves around nine million workers, is in deep crisis, bringing thousands to the streets across Europe, with similar demands but various motivations.

Published on 8 February 2024

Olivier Ploux | Cartoon movement

The European agricultural sector is on the warpath. "Contagion or coincidence?" Lola García-Ajofrín asks in Spain's El Confidencial: "The images from Romania are very similar to those from Germany, where in early January tens of thousands of people blocked the highways with their tractors. In that case, the protests were against a series of cuts in farm vehicle and fuel subsidies. The protests also resemble those in Toulouse (France), and Ireland, where farmers marched with cows, or those in Poland, and Belgium [...]. Earlier, in the Netherlands, farmers went so far as to found a party and gain parliamentary representation. Since the Dutch tractor protests broke out just over a year ago, agricultural protests have occurred in more than 15 EU countries, according to monitoring by the think tank Farm Europe."

The European agricultural sector is on the warpath. "Contagion or coincidence?" Lola García-Ajofrín asks in Spain's El Confidencial: "The images from Romania are very similar to those from Germany, where in early January tens of thousands of people blocked the highways with their tractors. In that case, the protests were against a series of cuts in farm vehicle and fuel subsidies. The protests also resemble those in Toulouse (France), and Ireland, where farmers marched with cows, or those in Poland, and Belgium [...]. Earlier, in the Netherlands, farmers went so far as to found a party and gain parliamentary representation. Since the Dutch tractor protests broke out just over a year ago, agricultural protests have occurred in more than 15 EU countries, according to monitoring by the think tank Farm Europe."

More : Green populism: How the far-right embraces ecology

According to 2020 data from Eurostat, there are about 8.7 million farmers in Europe, only 11.9 percent of whom are under 40 years old. This figure represents a little over 2 percent of the electorate for the upcoming European elections. Since restructuring due to the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy), the number of farms in the EU has declined by more than a third since 2005, explains Jon Henley, Europe correspondent for The Guardian.

A Politico.eu map shows where protests have taken place and (briefly) for what reasons."In 11 EU countries, producer prices [base price farmers receive for their produce] fell by more than 10 percent from 2022 to 2023.Only Greece and Cyprus have seen a corresponding increase in farmers' sales revenues, thanks to increased demand for olive oil," writes Hanne Cokelaere and Bartosz Brzeziński.

Henley In The Guardian writes that "besides feeling persecuted by what they see as a Brussels bureaucracy that knows little about their business, many farmers complain they feel caught between apparently conflicting public demands for cheap food and climate-friendly processes." For many, it is not climate compliance that is causing the agricultural world to suffer, but "competition between farmers and the concentration of farms," as Véronique Marchesseau, farmer et secretary-general of the French leftist union Confédération paysanne, explains in Alternatives Economiques. At the same time, adds Nicolas Legendre, a journalist specializing in the topic, interviewed by Vert, there is also a "visceral anger from part of the agricultural world toward environmentalists (and environmentalism in general), fueled by certain agro-industrial players."

While the press has a tendency to report on a "movement," the agricultural world is not monolithic. The mobilisation of European farmers emerges from a sector that is diverse in not only the modes of production, but also in worldview, political orientation, income level and social class.

More : Lucas Chancel: ‘Those who are most affected are those who pollute the least’

In Reporterre, a site specialising in ecology and social struggles that we often feature in Voxeurop, we learn that in France the average area of a farm is 96 hectares. Arnaud Rousseau, leader of FNSEA, the majority union of French farmers, owns a 700-hectare farm. Why would I mention Rousseau? Because, to return to the question of movements - who they represent, and who is represented - it is important to mention when a leading voice of a protest movement is that of an agribusiness oligarch. A portrait/investigation by Amélie Poinssot for Mediapart clarifies the political dimension: "He is the head of a giant of the French economy: Avril-Sofiprotéol, a giant of so-called seed oil and protein crops, founded by the trade union. It is no less than the fourth largest agribusiness group in France."

As Ingwar Perowanowitsch explains in taz, "there are powerful agricultural holding companies that receive up to 5 million euro in subsidies per year. And there are small family farms that receive a few hundred euro. There is animal husbandry and cultivation. There are conventional and organic farmers. Some produce for the world market, others for the weekly market." The German newspaper quotes a farmer from Leipzig, who works for a cooperative farm, who decided not to demonstrate in January due to the infiltration of the far right, and because he did not feel represented: "the farmers' association defends the interests of large companies that produce for the world market and not those of small-scale agriculture."

Farmers and violence: double standards

For Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, "many of the farmers' concerns are legitimate", as Le Soir reports, in the wake of demonstrations that saw thousands of farmers in Brussels light fires and throw eggs at the European Parliament building on 1 February. In El Pais Marc Bassets writes that "power fears them. The majority of the population looks at them with distance and respect."

This is an attitude that finds its peak in France, where the difference in treatment of protesters at the hands of police is flagrant. Europe has denounced the excessive violence of the police, first and foremost toward the Gilets Jaunes, but also various demonstrations around the country (against pension reforms, or during the riots in the banlieues), and finally the use of 5,000 grenades against the "ecoterrorists" in Sainte-Soline.

In recent days farmers have not only blocked roads and highways, or poured straw and manure, but also detonated a bomb in one building, and set fire to another. But no one is talking about "agroterrorism," and the police have never intervened. Quite the contrary, in fact. As for the minister of the interior, Gérard Darmanin, he abandoned his usual martial tone by expressing on TF1 his "compassion" for the farmers and stating that "you don't respond to suffering by sending CRS [riot police], voilà."

"Since World War II, public authorities have tolerated from farmers what they would not tolerate from other social groups," historian Edouard Lynch, an expert in rural studies, tells Libération. Moreover, not all farmers are equal: "Even within farmer movements, the state targets minority groups, as shown by the repression of demonstrations against the mega-basins in Sainte-Soline," in Western France, Lynch continues. On Arrêt sur Images, Lynch adds, "One can see today [in the face of these demonstrations] how the violence we have witnessed in recent years is the result of the strategies of the forces of law and order. [...] The violence of social movements is provoked by the keepers of the peace: decisions are made to move toward confrontation in order to stigmatise the opponent." Behind this, he explains, is a kind of national mythology of the "good farmer who feeds the nation."

Lynch is echoed by Thin Lei Win in Green European Journal: there is "a positive European-wide image of farmers as custodians of rural traditions and cultural heritage, as well as providers of our livelihood. This means that a much larger part of the electorate sympathises and identifies with them."

In partnership with Display Europe, cofunded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Directorate‑General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

No comments:

Post a Comment