Canadian provinces to borrow 22% more this year as deficits rise

, Bloomberg News

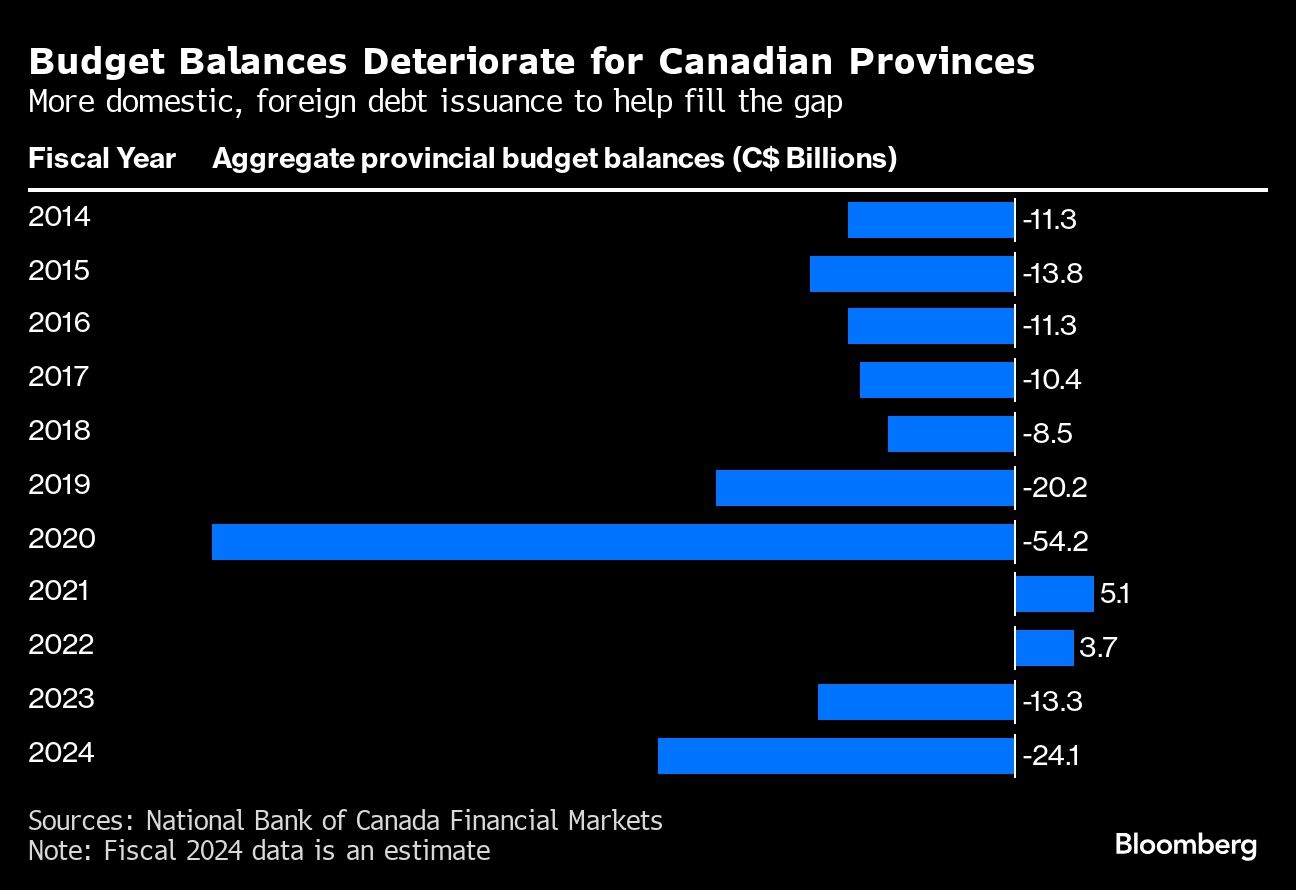

Canadian provinces are set to issue more debt than they did last year as they look to plug budget shortfalls, according to National Bank of Canada’s financial markets unit.

Borrowing needs from provinces facing growing deficits and maturing debt are estimated to be $130 billion for the fiscal year starting April 1, the highest in four years, data compiled by the division showed. That’s a 21.5 per cent jump from $107 billion for the prior fiscal year.

The growing financing requirements come as borrowing costs have stayed elevated because of persistent inflation. While that doesn’t bode well for issuers, it could be a boon for investors looking to lock in higher yields before central banks in Canada and across the world cut interest rates. On Tuesday, traders upped their bets on a June rate cut by the Bank of Canada as inflation slowed in February.

“A fairly sizable aggregate borrowing requirement and a still uncertain economic and financial backdrop means the provinces are going to be motivated to get funding in the door when they have an opportunity to do so,” said Warren Lovely, chief rates and public sector strategist at the National Bank of Canada Financial Markets.

There has been already been flurry of issuance from Canadian provinces. Quebec, Canada’s second-largest province, borrowed €2.25 billion of bonds due in 10 years, on top of issuing three Canada dollar-bonds totaling $1.95 billion. It expects a budget shortfall of $11 billion in the fiscal year that begins April 1 — $8 billion more than it previously forecast — and anticipates issuing $36.5 billion in new debt in the 2024-2025 fiscal year.

Among other provinces, British Columbia tapped the Canadian bond Tuesday and Manitoba borrowed $300 million last week.

The heightened borrowing needs across provinces won’t necessarily flood Canada’s bond market as international markets will also be utilized, said Lovely. Provinces also tend to issue more longer-dated debt than the federal government, which limits certain risks, said Marc Desormeaux, principal economist, Canadian Economics at Desjardins Group.

That said, bigger-than-anticipated deficits make the road ahead more challenging for prospective issuers.

“Governments running bigger deficits will be under more pressure to demonstrate fiscal responsibility to their creditors, leaving less room to support the economy in the event of a downturn,” said Desormeaux.

No comments:

Post a Comment