The Farming Conundrum

Agriculture is a big contributor to climate change — is there a path to reinvention?

Closing the knowledge gap

Farming accounts for about a third of the world’s carbon emissions, and a 10th of America’s. But we still know shockingly little about how to reduce its toll on the climate and vulnerable ecosystems.

I spoke to a number of experts for this newsletter. Though some of them were generally supportive of investing in some climate-smart practices, they told me that even practices that are generally recognized as good for the climate still have unclear benefits.

Take cover crops, one of the most accepted climate-smart farming practices. These are legumes and other species that are planted after the harvest of cash crops, such as corn, to help nourish the soil and improve water quality.

Most people agree that implementing cover crops on a large scale could help reduce emissions. But those conclusions rely on a relatively small amount of data, Novick told me.

The Inflation Reduction Act and other funding streams are directing hundreds of millions of dollars to improve data and models. That, the U.S.D.A. spokesman said, will “ensure that future resources are directed to the most effective practices.”

Doria Gordon, a senior director at the Environmental Defense Fund, told me she is excited about “the unprecedented level of funding” the agriculture sector is getting to become more sustainable and that many practices the U.S.D.A. is supporting should have climate benefits if implemented at scale.

Still, she would like the agency to take its efforts to collect data further. There is also “an equally unprecedented opportunity” to close the knowledge gap, she said. “This really is a once in-a-lifetime chance to advance our understanding of these emerging solutions.”

Is the USDA’s spending on ‘climate-smart’ farming actually helping the climate?Agriculture is a big contributor to climate change — is there a path to reinvention?

A new report found that the United States is spending billions of dollars to try to slash greenhouse gas emissions from farms, but many of the new practices are unproven.

Credit...Tim Gruber for The New York Times

By Manuela Andreoni

Feb. 29, 2024

Two news stories this week — one that made headlines, and one that got less attention — point to the fiendish difficulty of reinventing agriculture to reduce its heavy toll on the climate.

The first development: The New York attorney general Letitia James, fresh off a $450 million civil verdict against Donald Trump, announced a lawsuit against JBS, the world’s biggest meatpacking company, for making misleading statements about its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

James’s lawsuit said that JBS has “used greenwashing and misleading statements to capitalize on consumers’ increasing desire to make environmentally friendly choices,” with statements such as: “Agriculture can be part of the climate solution. Bacon, chicken wings, and steak with net zero emissions. It’s possible.”

The lawsuit cited David Gelles’s interview with Gilberto Tomazoni, the chief executive of JBS, at our Climate Forward event in September in which he said: “We pledge to be net zero in 2040.”

James argues the company can’t possibly achieve net zero “because there are no proven agricultural practices to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions” at the company’s vast scale, at least without costly efforts to offset its emissions.

JBS is a gigantic company, but the issues raised in the lawsuit against its U.S. arm are even fundamental: Is there even a path to net zero agriculture, especially if people are determined to keep large quantities of meat in their diets?

Climate-smart agriculture

The second development this week speaks to that problem: A new report found that the United States is spending billions of dollars to try to slash greenhouse gas emissions from farms. Sounds great, but there’s a hitch: much of the money may go to projects that won’t necessarily serve that goal.

The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit group that conducted the research, said that the United States Department of Agriculture is poised to fund a number of unproven practices. Those include installing new irrigation systems, despite the harm they can cause to groundwater supplies, and building infrastructure to contain animal waste, which could in fact lead to more emissions of methane and other greenhouse gases.

Allan Rodriguez, a U.S.D.A. spokesman, said in a statement that the EWG report is “fundamentally flawed” because it “did not take into account the rigorous, science-based methodology used by USDA to determine eligible practices” or the level of specificity that is required for some practices to receive climate funding.

Anne Schechinger, the author of the EWG report, told me that she is still waiting for the U.S.D.A. to share its sources and data that would justify the climate-smart designation.

The Biden Administration’s Environmental AgendaNarrowing Two Big Climate Rules: President Biden’s climate ambitions are colliding with political and legal realities, forcing his administration to recalibrate two regulations aimed at cutting the emissions that are heating the planet: one requiring gas-burning power plants to cut their carbon dioxide emissions and one designed to sharply limit tailpipe emissions.

Chemical Facilities: The Biden administration issued new rules designed to prevent disasters at almost 12,000 chemical plants and other industrial sites nationwide that handle hazardous materials.

Fuel Ban: The Biden administration will permanently lift a ban on summertime sales of higher-ethanol gasoline blends in eight states starting in 2025, in response to a request from Midwestern governors.

Biden’s Climate Law: A year and a half after President Biden signed into law a sweeping bill to tackle climate change, an analysis of the legislation’s effects has found that electric vehicles are booming as expected but renewable power isn’t growing as quickly as hoped.

Even setting aside that particular dispute, one thing is clear: There is a huge knowledge gap in our efforts to transform agriculture. Measuring agricultural emissions is a lot more complex than monitoring power plants and tailpipes. That makes it hard for any government to measure how well such techniques are working — or if in some cases they’re actually doing more harm than good.

“The pace at which these strategies are being implemented is greatly outpacing the speed at which the science, knowledge necessary to understand their effectiveness is being generated,” said Kim Novick, an environmental scientist at Indiana University who studies carbon in agricultural systems. “Until we close that gap, it’s really a lot of putting the cart before the horse.”

By Manuela Andreoni

Feb. 29, 2024

Two news stories this week — one that made headlines, and one that got less attention — point to the fiendish difficulty of reinventing agriculture to reduce its heavy toll on the climate.

The first development: The New York attorney general Letitia James, fresh off a $450 million civil verdict against Donald Trump, announced a lawsuit against JBS, the world’s biggest meatpacking company, for making misleading statements about its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

James’s lawsuit said that JBS has “used greenwashing and misleading statements to capitalize on consumers’ increasing desire to make environmentally friendly choices,” with statements such as: “Agriculture can be part of the climate solution. Bacon, chicken wings, and steak with net zero emissions. It’s possible.”

The lawsuit cited David Gelles’s interview with Gilberto Tomazoni, the chief executive of JBS, at our Climate Forward event in September in which he said: “We pledge to be net zero in 2040.”

James argues the company can’t possibly achieve net zero “because there are no proven agricultural practices to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions” at the company’s vast scale, at least without costly efforts to offset its emissions.

JBS is a gigantic company, but the issues raised in the lawsuit against its U.S. arm are even fundamental: Is there even a path to net zero agriculture, especially if people are determined to keep large quantities of meat in their diets?

Climate-smart agriculture

The second development this week speaks to that problem: A new report found that the United States is spending billions of dollars to try to slash greenhouse gas emissions from farms. Sounds great, but there’s a hitch: much of the money may go to projects that won’t necessarily serve that goal.

The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit group that conducted the research, said that the United States Department of Agriculture is poised to fund a number of unproven practices. Those include installing new irrigation systems, despite the harm they can cause to groundwater supplies, and building infrastructure to contain animal waste, which could in fact lead to more emissions of methane and other greenhouse gases.

Allan Rodriguez, a U.S.D.A. spokesman, said in a statement that the EWG report is “fundamentally flawed” because it “did not take into account the rigorous, science-based methodology used by USDA to determine eligible practices” or the level of specificity that is required for some practices to receive climate funding.

Anne Schechinger, the author of the EWG report, told me that she is still waiting for the U.S.D.A. to share its sources and data that would justify the climate-smart designation.

The Biden Administration’s Environmental AgendaNarrowing Two Big Climate Rules: President Biden’s climate ambitions are colliding with political and legal realities, forcing his administration to recalibrate two regulations aimed at cutting the emissions that are heating the planet: one requiring gas-burning power plants to cut their carbon dioxide emissions and one designed to sharply limit tailpipe emissions.

Chemical Facilities: The Biden administration issued new rules designed to prevent disasters at almost 12,000 chemical plants and other industrial sites nationwide that handle hazardous materials.

Fuel Ban: The Biden administration will permanently lift a ban on summertime sales of higher-ethanol gasoline blends in eight states starting in 2025, in response to a request from Midwestern governors.

Biden’s Climate Law: A year and a half after President Biden signed into law a sweeping bill to tackle climate change, an analysis of the legislation’s effects has found that electric vehicles are booming as expected but renewable power isn’t growing as quickly as hoped.

Even setting aside that particular dispute, one thing is clear: There is a huge knowledge gap in our efforts to transform agriculture. Measuring agricultural emissions is a lot more complex than monitoring power plants and tailpipes. That makes it hard for any government to measure how well such techniques are working — or if in some cases they’re actually doing more harm than good.

“The pace at which these strategies are being implemented is greatly outpacing the speed at which the science, knowledge necessary to understand their effectiveness is being generated,” said Kim Novick, an environmental scientist at Indiana University who studies carbon in agricultural systems. “Until we close that gap, it’s really a lot of putting the cart before the horse.”

Closing the knowledge gap

Farming accounts for about a third of the world’s carbon emissions, and a 10th of America’s. But we still know shockingly little about how to reduce its toll on the climate and vulnerable ecosystems.

I spoke to a number of experts for this newsletter. Though some of them were generally supportive of investing in some climate-smart practices, they told me that even practices that are generally recognized as good for the climate still have unclear benefits.

Take cover crops, one of the most accepted climate-smart farming practices. These are legumes and other species that are planted after the harvest of cash crops, such as corn, to help nourish the soil and improve water quality.

Most people agree that implementing cover crops on a large scale could help reduce emissions. But those conclusions rely on a relatively small amount of data, Novick told me.

The Inflation Reduction Act and other funding streams are directing hundreds of millions of dollars to improve data and models. That, the U.S.D.A. spokesman said, will “ensure that future resources are directed to the most effective practices.”

Doria Gordon, a senior director at the Environmental Defense Fund, told me she is excited about “the unprecedented level of funding” the agriculture sector is getting to become more sustainable and that many practices the U.S.D.A. is supporting should have climate benefits if implemented at scale.

Still, she would like the agency to take its efforts to collect data further. There is also “an equally unprecedented opportunity” to close the knowledge gap, she said. “This really is a once in-a-lifetime chance to advance our understanding of these emerging solutions.”

More climate news

Despite ongoing protests by farmers, the European Union approved a landmark bill to restore 20 percent of its land and sea ecosystems by 2030, The Guardian reports.

Cities across the world are stripping out concrete to make room for earth and plants, the BBC reports.

Exxon’s chief told Fortune magazine that “people generating the emissions” need to pay the price.

Manuela Andreoni is a Times climate and environmental reporter and a writer for the Climate Forward newsletter. More about Manuela Andreoni

Despite ongoing protests by farmers, the European Union approved a landmark bill to restore 20 percent of its land and sea ecosystems by 2030, The Guardian reports.

Cities across the world are stripping out concrete to make room for earth and plants, the BBC reports.

Exxon’s chief told Fortune magazine that “people generating the emissions” need to pay the price.

Manuela Andreoni is a Times climate and environmental reporter and a writer for the Climate Forward newsletter. More about Manuela Andreoni

A new report asks whether supposedly green livestock practices have proven benefits.

AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

Max Graham

Max Graham

Food and Agriculture Fellow

Mar 01, 2024

America’s farms don’t just run on corn and cattle. They also run on cash from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Every year, the USDA spends billions of dollars to keep farmers in business. It hands out money to balance fluctuations in crop prices; it provides loans for farmers who want to buy livestock or seeds; and it pays growers who lose crops to drought, floods, and other extreme weather.

The agency is also now giving money — including $20 billion that Congress earmarked two years ago in the Inflation Reduction Act — to farmers trying to curb their greenhouse gas emissions and store carbon in soil, a key part of the Biden administration’s goal to cut the 10 percent of the country’s emissions generated by agriculture. That windfall of climate-smart farm funding has been widely lauded by climate activists and researchers.

But exactly how the USDA spends that money is more complicated — and contentious — than it might appear, and not simply because Republicans in Congress have threatened to siphon the funds away. A new report from the Environmental Working Group says that more than a dozen of the farming practices that the USDA recently designated as “climate-smart”— including several of the highest-funded ones — don’t actually have proven climate benefits. That finding is especially important, according to the group, because the USDA is likely to spend more money on the same practices in the years to come: Much of the $20 billion authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act has yet to reach farmers’ pockets.

Supporting farming techniques with uncertain benefits “undermines potentially real reductions in emissions,” said Anne Schechinger, author of the report and Midwest director at the Environmental Working Group, an environmental research and advocacy organization. “If these unproven practices stay on the list, then a lot of money will go to these practices that likely aren’t going to reduce emissions.”

A USDA spokesperson said the agency uses a rigorous, scientific process to determine what it considers climate-smart. Still, the agency acknowledges that not everything on its list necessarily has quantifiable benefits. New additions to the list are provisional — that is, they’re added “under the premise that they may provide benefits” and will be removed later on if those benefits can’t be quantified.

Schechinger analyzed spending by the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program, called EQIP for short, the agency’s biggest conservation program. She found that, between 2017 and 2022, the program directed around $2 billion to techniques that were added provisionally to its climate-smart list for this fiscal year.

“It looks like a lot of money is going to climate-smart practices between 2017 and 2022 when, really, very little of the total EQIP money has actually gone to practices with proven climate benefits,” said Schechinger.

In particular, the group called into question eight of 15 methods that the Biden administration added provisionally, such as installing a waste facility cover or an irrigation pipeline. One of them — “waste storage facility,” a structure that holds manure and other agricultural waste — may even increase emissions, according to the report. The USDA spent about $250 million on them between 2017 and 2022.

The department specifies on its list that only a specific kind of waste storage facility, one that composts manure, counts as climate-smart. These composting structures can reduce methane emissions and improve water quality, the agency says.

“Unfortunately, EWG did not take into account the rigorous, science-based methodology used by USDA to determine eligible practices, nor the level of specificity required during the implementation process to ensure the practices’ climate-smart benefits are being maximized,” said Allan Rodriguez, a spokesperson for the USDA, in an emailed statement. “As a result, the findings of this report are fundamentally flawed, speculative, and rest on incorrect assumptions around USDA’s selection of climate-smart practices.”

Schechinger acknowledged that the USDA doesn’t define all waste storage facilities as climate-smart, but she said that the funding data she was able to obtain through a records request didn’t distinguish between specific facility types and that it “remains to be seen” whether the Inflation Reduction Act money will go only to the kind that composts manure.

Some researchers have argued that more studies need to be done on most “climate-smart” practices — even ones, such as planting cover crops, that the Environmental Working Group doesn’t question in its report — before anyone can say how much climate pollution they’re curbing or carbon they’re sequestering. “For most climate-smart management practices, we do not yet have the data and information we need to understand when and where they are most likely to succeed,” said Kim Novick, an environmental scientist at Indiana University.

Most scientists agree that more data needs to be collected and analyzed to understand, say, the nuances of storing carbon in the soil. But some argue that climate change is just too urgent to delay action.

That’s one reason Rachel Schattman, a professor of sustainable agriculture at the University of Maine, supports the USDA’s use of climate funding. She also has confidence in the agency’s commitment to science. A practice doesn’t get put on the agency’s conservation list “without having demonstrated environmental benefits or reduced environmental harm,” she said. “Whether those benefits or reduced harms are related to climate change is something [the USDA] is grappling with in a really meaningful way right now.”

Schattman also said it’s important not to paint climate-smart practices with a broad brush. “Everybody’s farm is different. Everybody’s soil is different. Everybody’s microclimate is different,” she said. An irrigation pipeline in the Arizona desert might have a different effect on water and energy use than one on a farm in Vermont. Even if a practice here or there doesn’t reduce emissions or store carbon in the soil exactly how the USDA intends, Schattman said the influx of funding still could move agriculture in the right direction.

The Inflation Reduction Act created “a once in a lifetime opportunity for a lot of farmers,” she said. “I think it is going to make a lot of things possible that people couldn’t do before.”

Grist is the only award-winning newsroom focused on exploring equitable solutions to climate change. It’s vital reporting made entirely possible by loyal readers like you. At Grist, we don’t believe in paywalls. Instead, we rely on our readers to pitch in what they can so that we can continue bringing you our solution-based climate news.

Mar 01, 2024

America’s farms don’t just run on corn and cattle. They also run on cash from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Every year, the USDA spends billions of dollars to keep farmers in business. It hands out money to balance fluctuations in crop prices; it provides loans for farmers who want to buy livestock or seeds; and it pays growers who lose crops to drought, floods, and other extreme weather.

The agency is also now giving money — including $20 billion that Congress earmarked two years ago in the Inflation Reduction Act — to farmers trying to curb their greenhouse gas emissions and store carbon in soil, a key part of the Biden administration’s goal to cut the 10 percent of the country’s emissions generated by agriculture. That windfall of climate-smart farm funding has been widely lauded by climate activists and researchers.

But exactly how the USDA spends that money is more complicated — and contentious — than it might appear, and not simply because Republicans in Congress have threatened to siphon the funds away. A new report from the Environmental Working Group says that more than a dozen of the farming practices that the USDA recently designated as “climate-smart”— including several of the highest-funded ones — don’t actually have proven climate benefits. That finding is especially important, according to the group, because the USDA is likely to spend more money on the same practices in the years to come: Much of the $20 billion authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act has yet to reach farmers’ pockets.

Supporting farming techniques with uncertain benefits “undermines potentially real reductions in emissions,” said Anne Schechinger, author of the report and Midwest director at the Environmental Working Group, an environmental research and advocacy organization. “If these unproven practices stay on the list, then a lot of money will go to these practices that likely aren’t going to reduce emissions.”

A USDA spokesperson said the agency uses a rigorous, scientific process to determine what it considers climate-smart. Still, the agency acknowledges that not everything on its list necessarily has quantifiable benefits. New additions to the list are provisional — that is, they’re added “under the premise that they may provide benefits” and will be removed later on if those benefits can’t be quantified.

Schechinger analyzed spending by the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program, called EQIP for short, the agency’s biggest conservation program. She found that, between 2017 and 2022, the program directed around $2 billion to techniques that were added provisionally to its climate-smart list for this fiscal year.

“It looks like a lot of money is going to climate-smart practices between 2017 and 2022 when, really, very little of the total EQIP money has actually gone to practices with proven climate benefits,” said Schechinger.

In particular, the group called into question eight of 15 methods that the Biden administration added provisionally, such as installing a waste facility cover or an irrigation pipeline. One of them — “waste storage facility,” a structure that holds manure and other agricultural waste — may even increase emissions, according to the report. The USDA spent about $250 million on them between 2017 and 2022.

The department specifies on its list that only a specific kind of waste storage facility, one that composts manure, counts as climate-smart. These composting structures can reduce methane emissions and improve water quality, the agency says.

“Unfortunately, EWG did not take into account the rigorous, science-based methodology used by USDA to determine eligible practices, nor the level of specificity required during the implementation process to ensure the practices’ climate-smart benefits are being maximized,” said Allan Rodriguez, a spokesperson for the USDA, in an emailed statement. “As a result, the findings of this report are fundamentally flawed, speculative, and rest on incorrect assumptions around USDA’s selection of climate-smart practices.”

Schechinger acknowledged that the USDA doesn’t define all waste storage facilities as climate-smart, but she said that the funding data she was able to obtain through a records request didn’t distinguish between specific facility types and that it “remains to be seen” whether the Inflation Reduction Act money will go only to the kind that composts manure.

Some researchers have argued that more studies need to be done on most “climate-smart” practices — even ones, such as planting cover crops, that the Environmental Working Group doesn’t question in its report — before anyone can say how much climate pollution they’re curbing or carbon they’re sequestering. “For most climate-smart management practices, we do not yet have the data and information we need to understand when and where they are most likely to succeed,” said Kim Novick, an environmental scientist at Indiana University.

Most scientists agree that more data needs to be collected and analyzed to understand, say, the nuances of storing carbon in the soil. But some argue that climate change is just too urgent to delay action.

That’s one reason Rachel Schattman, a professor of sustainable agriculture at the University of Maine, supports the USDA’s use of climate funding. She also has confidence in the agency’s commitment to science. A practice doesn’t get put on the agency’s conservation list “without having demonstrated environmental benefits or reduced environmental harm,” she said. “Whether those benefits or reduced harms are related to climate change is something [the USDA] is grappling with in a really meaningful way right now.”

Schattman also said it’s important not to paint climate-smart practices with a broad brush. “Everybody’s farm is different. Everybody’s soil is different. Everybody’s microclimate is different,” she said. An irrigation pipeline in the Arizona desert might have a different effect on water and energy use than one on a farm in Vermont. Even if a practice here or there doesn’t reduce emissions or store carbon in the soil exactly how the USDA intends, Schattman said the influx of funding still could move agriculture in the right direction.

The Inflation Reduction Act created “a once in a lifetime opportunity for a lot of farmers,” she said. “I think it is going to make a lot of things possible that people couldn’t do before.”

Grist is the only award-winning newsroom focused on exploring equitable solutions to climate change. It’s vital reporting made entirely possible by loyal readers like you. At Grist, we don’t believe in paywalls. Instead, we rely on our readers to pitch in what they can so that we can continue bringing you our solution-based climate news.

New USDA 'climate-friendly' farming and ranching practices have yet to be proven, report says

March 1, 2024

March 1, 2024

A cow grazes in a field outside of Walcott, Iowa.

An environmental activist group charges that many “climate smart” farming practices recently added to a list for U.S. Department of Agriculture funding are not yet proven.

The Environmental Working Group says funding from the Inflation Reduction Act should not be used to pay farmers for using the practices, until there is more evidence that they work.

The EWG made the charge in a new report issued Wednesday about the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP.

The program, run by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, was launched in the 1990s, but its current authorization comes from the 2018 Farm Bill. EQIP helps farmers with funding to implement conservation methods that have met the department’s approval. Since 2023, its funding sources have included money authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act to fund climate change mitigation efforts.

But the EWG report says many of the 15 practices earmarked for that funding “likely do little or nothing to help in the climate fight.”

“USDA says that they have literature showing that these practices have climate benefits,” said agricultural economist and EWG Midwest Director Anne Schechinger, who authored the report. “But they don't actually have any quantifiable data showing that these practices reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

She said eight of the 15 practices are for irrigation and livestock, management techniques “that likely don’t reduce emissions,” and in one case, may even increase emissions.

Funding from the Inflation Reduction Act specifically meant for addressing climate change should be reserved for practices proven to be effective, Schechinger said. While the USDA’s NRCS plans to study the possible benefits of the new farming practices this year, she said until the results of those studies are in, the practices should be removed from eligibility for IRA funding.

New Practices:

brush management

irrigation system, sprinkler

waste storage facility

irrigation pipeline

waste facility cover

irrigation system, micro

pumping plant

woody residue treatment

herbaceous weed control

prescribed burning

wildlife habitat–restore and management

fuel break

composting facility

feed management

soil carbon amendment

The USDA is defending the EQIP program’s climate-smart agriculture practices.

In a statement, spokesman Allan Rodriguez said the department used “rigorous, science-based methodology” to determine which practices are eligible — and that farmers who qualify for funding must use the practices under specific conditions to maximize their effectiveness.

Rodriguez said the Environmental Working Group’s findings were “fundamentally flawed, speculative, and rest on incorrect assumptions around USDA’s selection of climate-smart practices.”

Jonathan Coppess, who researches federal ag policy as an associate professor at the University of Illinois, said the EWG report does raise valid concerns. He said that while he can sympathize with the USDA’s position, he points out that Inflation Reduction Act funding is scheduled to end after the 2026 fiscal year.

“Once the funds are out, you can’t pull them back,” said Coppess. “And so, if they are misspent, it's a missed opportunity in a significant way to do what is an important effort for agriculture, for our food system, and for the climate.”

But according to Erik Lichtenberg, there are more benefits to the practices in question than the EWG report credits. The University of Maryland agricultural economist, who has studied the USDA’s approach to conservation and climate change, said paying farmers to implement practices that are not fully proven is a way to find out how they work under a wide range of conditions and climates.

“We're fairly new to managing agriculture to mitigate climate change impacts, and that means we really need to be experimenting to see what does work and what doesn't,” Lichtenberg said. “Farming practices that work in one place, don't work in another. So, we're really going to need to experiment a lot and adjust for local conditions a lot.”

The USDA has funded only about a third of the applications they received from farmers for the EQIP program between fiscal year 2018 and 2022.

The USDA’s Rodriguez said the additional funding from the Inflation Reduction Act is expanding the number of farmers EQIP can serve, and also financing efforts to monitor and verify the effectiveness of new practices.

He said those efforts will enable them to “quantify the impact of conservation practices on greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration and ensure that future resources are directed to the most effective practices.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.

An environmental activist group charges that many “climate smart” farming practices recently added to a list for U.S. Department of Agriculture funding are not yet proven.

The Environmental Working Group says funding from the Inflation Reduction Act should not be used to pay farmers for using the practices, until there is more evidence that they work.

The EWG made the charge in a new report issued Wednesday about the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP.

The program, run by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, was launched in the 1990s, but its current authorization comes from the 2018 Farm Bill. EQIP helps farmers with funding to implement conservation methods that have met the department’s approval. Since 2023, its funding sources have included money authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act to fund climate change mitigation efforts.

But the EWG report says many of the 15 practices earmarked for that funding “likely do little or nothing to help in the climate fight.”

“USDA says that they have literature showing that these practices have climate benefits,” said agricultural economist and EWG Midwest Director Anne Schechinger, who authored the report. “But they don't actually have any quantifiable data showing that these practices reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

She said eight of the 15 practices are for irrigation and livestock, management techniques “that likely don’t reduce emissions,” and in one case, may even increase emissions.

Funding from the Inflation Reduction Act specifically meant for addressing climate change should be reserved for practices proven to be effective, Schechinger said. While the USDA’s NRCS plans to study the possible benefits of the new farming practices this year, she said until the results of those studies are in, the practices should be removed from eligibility for IRA funding.

New Practices:

brush management

irrigation system, sprinkler

waste storage facility

irrigation pipeline

waste facility cover

irrigation system, micro

pumping plant

woody residue treatment

herbaceous weed control

prescribed burning

wildlife habitat–restore and management

fuel break

composting facility

feed management

soil carbon amendment

The USDA is defending the EQIP program’s climate-smart agriculture practices.

In a statement, spokesman Allan Rodriguez said the department used “rigorous, science-based methodology” to determine which practices are eligible — and that farmers who qualify for funding must use the practices under specific conditions to maximize their effectiveness.

Rodriguez said the Environmental Working Group’s findings were “fundamentally flawed, speculative, and rest on incorrect assumptions around USDA’s selection of climate-smart practices.”

Jonathan Coppess, who researches federal ag policy as an associate professor at the University of Illinois, said the EWG report does raise valid concerns. He said that while he can sympathize with the USDA’s position, he points out that Inflation Reduction Act funding is scheduled to end after the 2026 fiscal year.

“Once the funds are out, you can’t pull them back,” said Coppess. “And so, if they are misspent, it's a missed opportunity in a significant way to do what is an important effort for agriculture, for our food system, and for the climate.”

But according to Erik Lichtenberg, there are more benefits to the practices in question than the EWG report credits. The University of Maryland agricultural economist, who has studied the USDA’s approach to conservation and climate change, said paying farmers to implement practices that are not fully proven is a way to find out how they work under a wide range of conditions and climates.

“We're fairly new to managing agriculture to mitigate climate change impacts, and that means we really need to be experimenting to see what does work and what doesn't,” Lichtenberg said. “Farming practices that work in one place, don't work in another. So, we're really going to need to experiment a lot and adjust for local conditions a lot.”

The USDA has funded only about a third of the applications they received from farmers for the EQIP program between fiscal year 2018 and 2022.

The USDA’s Rodriguez said the additional funding from the Inflation Reduction Act is expanding the number of farmers EQIP can serve, and also financing efforts to monitor and verify the effectiveness of new practices.

He said those efforts will enable them to “quantify the impact of conservation practices on greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration and ensure that future resources are directed to the most effective practices.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.

RESEARCH

Many newly labeled USDA climate-smart conservation practices lack climate benefits

JUMP TO:

What climate-smart practices should do

New practices probably don’t benefit climate

New list creates alternate reality of robust climate funding

Climate money will now go to different states

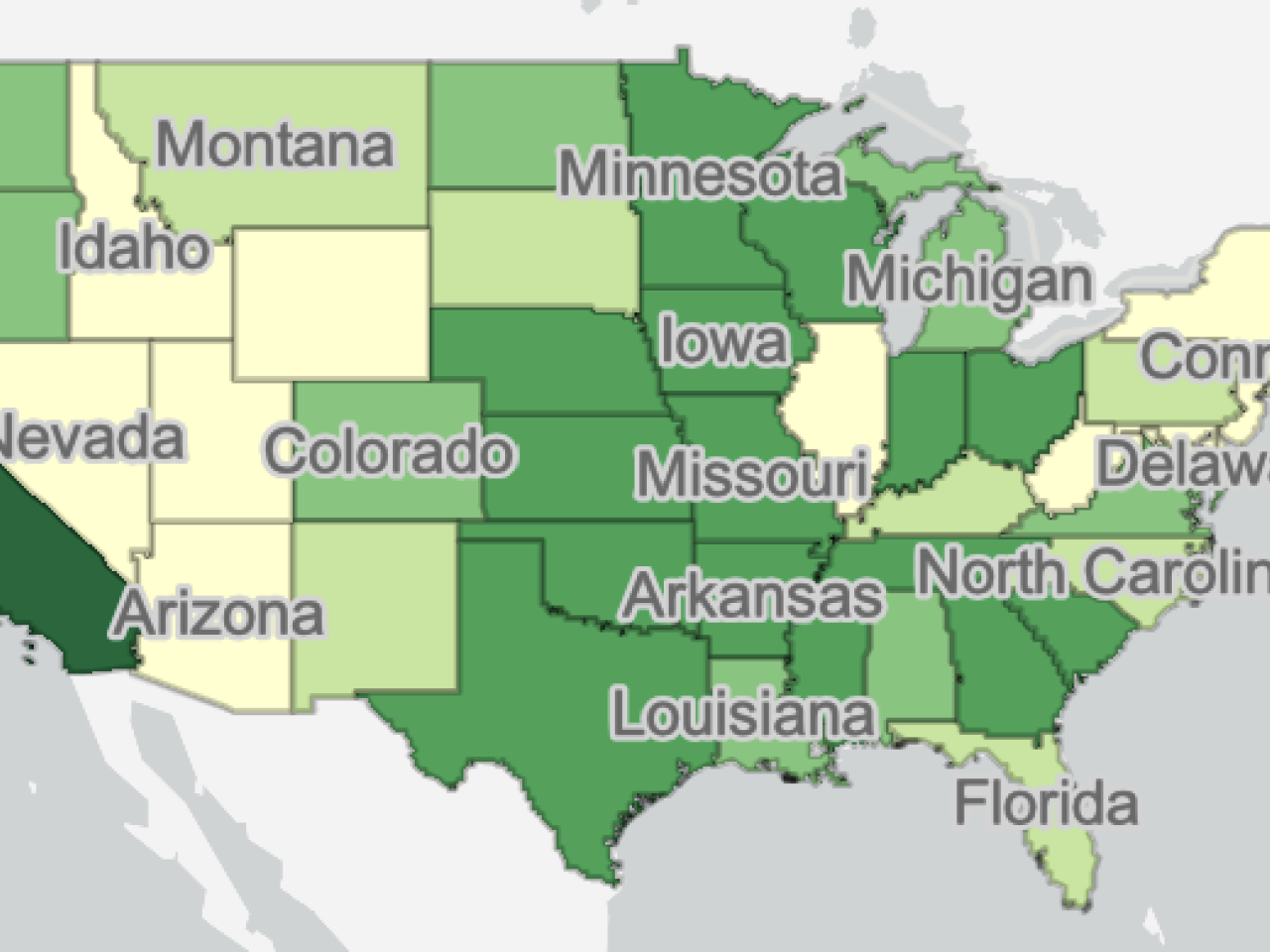

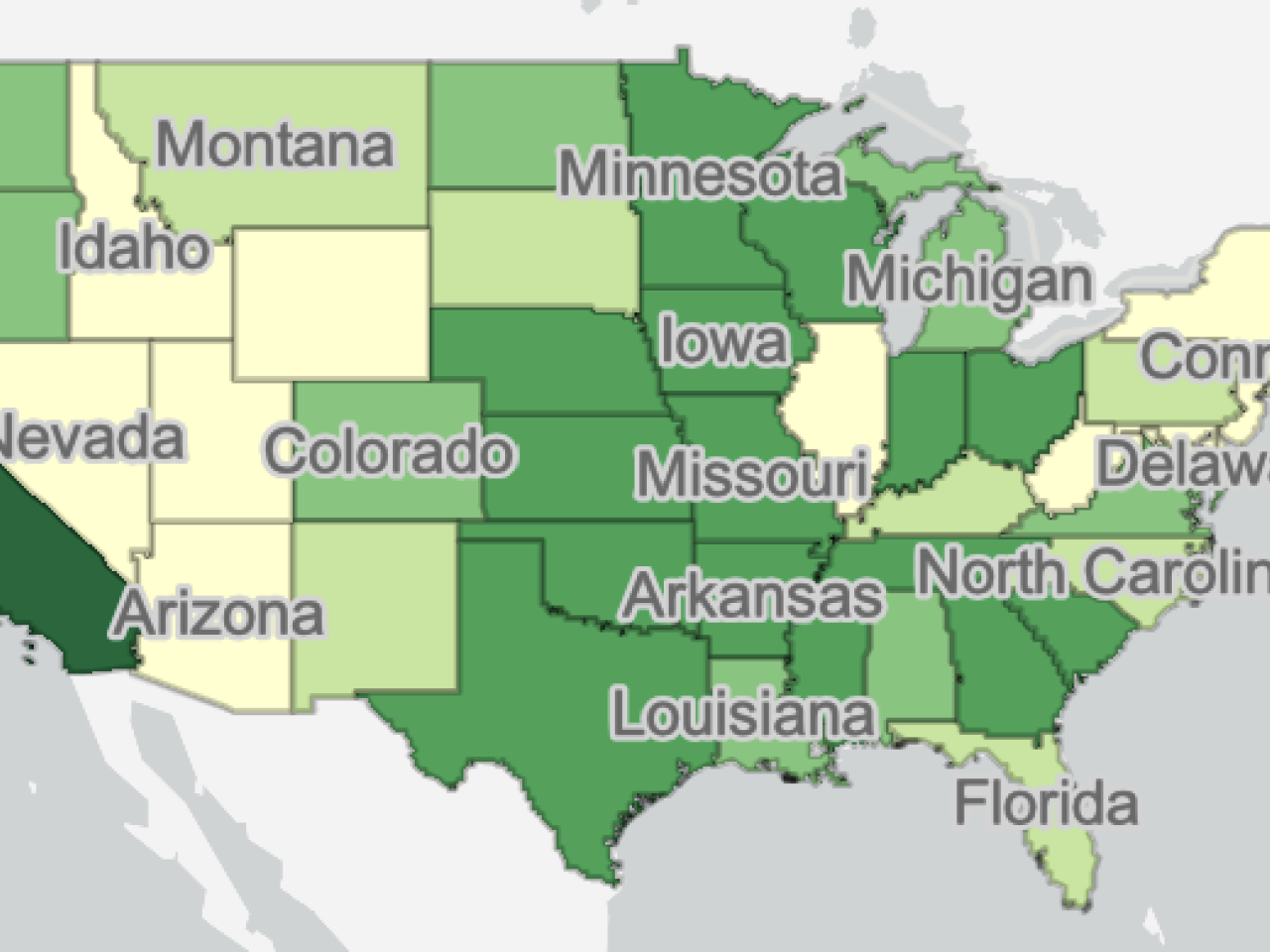

Map: Environmental Quality Incentives Program payments, 2017-2022

Analysis methodology

OverviewNewly designated USDA climate-smart conservation practices likely don’t reduce agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Only practices that reduce emissions are eligible for $19.5 billion in 2022 Inflation Reduction Act funds.

The new designations make it look, erroneously, like a lot of money is going to climate-smart agriculture.

Against the backdrop of the deepening climate crisis, the Department of Agriculture recently added 15 Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, practices to its climate-smart conservation list – but many likely do little or nothing to help in the climate fight, a new EWG analysis of USDA data finds.

The new data is compiled in EWG’s just-updated Conservation Database. EQIP is one of the USDA’s largest conservation programs, helping farmers implement environmentally beneficial practices.

Some of the newly designated climate-smart practices already receive, by far, the most dollars from EQIP. So the revision of the list conveniently makes it look as though a large share of federal conservation funding will now go to climate-smart farming, providing a misleading picture of agriculture and climate in the U.S.

In 2022, EWG found that only a small portion of EQIP funding went to farmers’ implementation of climate-smart methods. The USDA's new list changes the equation significantly, effectively doubling climate-smart funding: Instead of 31 percent of EQIP funds subsidizing climate-smart farming between 2017 and 2022, it now appears that 63 percent did.

And the new climate-smart practices are about to get even more money, because they’re eligible to receive additional funds through the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA. This money totals about $19.5 billion, $8.45 billion of which is meant specifically for EQIP practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon in soil between fiscal years 2023 and 2026.

But many of the newly labeled practices likely do not have climate benefits. Eight of them are methods for irrigation and livestock management that likely don’t reduce emissions. One even increases emissions, according to USDA’s own data.

The USDA’s conservation agency, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS, says that in 2024 it will study the possible climate benefits of the newly added practices.

Until then, the USDA should remove them from its climate-smart list. No IRA funds should underwrite them without proof they actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate-smart conservation is intended to provide real climate benefits

For the past few years, the NRCS has made a list of practices funded through EQIP and the Conservation Stewardship Program, one of its other tentpole conservation programs, that it considers climate-smart. The practices on this list are intended to cause “quantifiable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and/or increases in carbon sequestration.”

In fiscal year 2023, the NRCS climate-smart list included 45 EQIP practices for which farmers received payments at some point between 2017 and 2022. (Other practices on the list didn’t get funding.) The funded practices included those with proven climate benefits, such as “cover crops,” “nutrient management” and “grassed waterways.”

In October 2023, the NRCS updated its list of climate-smart practices for fiscal year 2024. The roster now has 57 EQIP practices that received funding between 2017 and 2022, including 15 new additions (not including two practices that were removed). (See Table 1.) Only 14 of the 15 newly added practices got any funding between 2017 and 2022. “Soil carbon amendment” was added to the list for 2024 but didn’t receive any funds.

Table 1. 2024 climate-smart EQIP practices.*

EQIP practices added to USDA's 2024 climate-smart conservation list

EQIP practices removed from USDA's climate-smart conservation list for 2024

Brush Management

Wildlife Upland Habitat Management

Irrigation System, Sprinkler

Waste Storage Facility

Irrigation Pipeline

Waste Facility Cover

Irrigation System, Micro

Pumping Plant

Woody Residue Treatment

Windbreak/Shelterbelt Renovation

Herbaceous Weed Control

Prescribed Burning

Wildlife Habitat- Restore and Management

Fuel Break

Composting Facility

Feed Management

*List only includes 14 practices that received money between 2017 and 2023. It does not include “Soil carbon amendment,” which did not.

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

Many practices newly labeled climate-smart likely don’t benefit the climate

Of the 14 newly added (and funded) practices, more than half – eight – are irrigation or livestock practices, such as “waste storage facility” and “irrigation pipeline.”

The NRCS is calling all of these practices “provisionally” climate-smart – it cannot yet show whether they reduce emissions, so they have no proven climate benefits.

And “waste storage facility,” a structure that contains animal waste, increases greenhouse gas emissions, according to the data USDA does have.

These livestock practices are almost certainly not climate-smart. Agriculture contributes more than 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, with livestock a major source – particularly beef and dairy cattle, which emit vast quantities of methane.

EQIP funding to manage large amounts of livestock in concentrated facilities encourages farmers to keep relying on this model instead of raising animals on pasture, which could help to lower emissions.

Irrigation practices are also not clearly climate-smart. Although EQIP irrigation practices seem to enable more efficient water use, they do not always reduce total water use, especially in the West, where many farmers’ water rights follow “use it or lose it” policies.

In these cases, if a water rights holder does not use all their water allocation, they forfeit the rest, so they have an incentive to use the most they can. So installing more efficient irrigation wouldn’t necessarily save any water.

The IRA text says $8.45 billion of its funding should go only to EQIP practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon in soil – in other words, to the practices on the NRCS climate-smart list.

So calling the livestock and irrigation practices climate-smart, provisionally or not, is problematic, since the IRA states that its agricultural funding should go to conservation practices that reduce emissions or sequester carbon.

The NRCS has said it will study provisional practices in 2024 to measure their greenhouse gas emission reductions, if any. It has also said if it does not find benefits, it may remove the provisional practices from the climate-smart list for the following year.

But history would show that these practices may not be studied in 2024: All eight provisional practices on the 2023 list remain on the list for 2024 – and all are still listed as provisional.

New list creates alternate reality where lots of money has gone to climate-smart farming

Some of the practices just added to the 2024 climate-smart list received the most EQIP funding between 2017 and 2022 – painting an inaccurate picture of a lot of money going to practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But because many of these new provisional practices likely do not reduce emissions, only a small share of EQIP spending is actually going to practices with proven climate benefits.

EQIP sent $5.5 billion to farmers across all practices between 2017 and 2022. Only $1.7 billion of this, or 31 percent, went to practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, most of which have been proven to reduce emissions or sequester carbon in soil.

But with the addition of the 14 funded provisional practices for 2024, that amount more than doubled to $3.47 billion – or 63 percent of all EQIP spending.

That’s because many of the practices added to the 2024 list are the most-funded practices in the whole program. The 10 practices with the most total EQIP payments made up $2.65 billion between 2017 and 2022 – almost half of all EQIP spending. Only two of these, “cover crops” and “forest stand improvement,” were on the 2023 climate-smart list.

But when the list was revised for 2024, eight of the 10 practices with the most program funding appeared on it. In addition to the two from 2023, these included “brush management”; “irrigation system – sprinkler”; “waste storage facility”; “irrigation pipeline”; “waste facility cover”; and “irrigation system – micro irrigation.” (See Table 2.) Five of these six practices are livestock or irrigation practices.

Of the 10 practices with the most EQIP payments, the only two not on the 2024 climate-smart list were “fence” and “pipeline,” which brings water to livestock or wildlife.

Table 2. Almost all the 10 EQIP practices with the most payments between 2017 and 2022 were added to the 2024 climate-smart practice list.

Practice rank

Practice name

EQIP payments 2017-2022

Percent of all EQIP payments

On 2023 climate-smart list?

On 2024 climate-smart list?

1

Cover Crop

$504,812,892

2

Brush Management

$314,991,152

3

Irrigation System, Sprinkler

$313,561,007

4

Fence

$311,036,533

5

Waste Storage Facility

$252,142,865

6

Irrigation Pipeline

$230,101,825

7

Waste Facility Cover

$228,568,531

8

Irrigation System, Micro

$175,194,972

9

Pipeline

$162,365,526

10

Forest Stand Improvement

$159,735,684

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

Addition of provisional practices to climate-smart list changes states receiving IRA funds

Expanding the climate-smart list will also change where the IRA money goes.

Across EQIP, payments are concentrated in just a few places – 44 percent of the money spent between 2017 and 2022 went to just 10 states. Similarly, 45 percent of payments to practices on the 2023 climate-smart list went to farmers in just 10 states, and 46 percent of payments to practices on the 2024 list went to farmers in the 10 states with the most payments.

When the list changed, so did the states that got the most climate-smart money. California and Texas were the top two on both lists, but the others changed drastically.

Seven of the top 10 states on the 2023 list were located in the Mississippi River Critical Conservation Area, a region of the country with important agricultural, industry, wildlife and ecological resources. But only four of the top 10 states on the 2024 climate-smart list were located in the conservation area (Table 3). Now Southern and Western states like Colorado, Georgia and Oregon will receive more so-called climate-smart funding.

Table 3. The 10 states that received the most payments between 2017 and 2022 for practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, compared to those on the 2024 list.

State rank States with the most payments for 2023 list Payments 2017-2022 for practices on 2023 list States with the most payments for 2024 list Payments 2017-2022 for practices on 2024 list

1 California $167,970,025 Texas $371,894,245

2 Texas $99,642,015 California $359,871,676

3 Missouri $69,273,408 Georgia $137,069,838

4 Indiana $65,270,184 Colorado $118,425,439

5 Tennessee $64,641,082 Arkansas $110,504,198

6 Wisconsin $57,753,631 Mississippi $100,305,742

7 Iowa $55,750,215 Oregon $93,274,547

8 Ohio $55,410,931 Oklahoma $91,351,469

9 Oklahoma $55,025,391 Indiana $91,034,785

10 Mississippi $54,055,521 Ohio $90,089,372

Total 10 states $744,792,403 Total top 10 states $1,563,821,311

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

The map below shows which states received the most money for practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, compared to those that got the most money for practices on the 2024 list.

INTERACTIVE MAP

Environmental Quality Incentives Program payments

This application provides details about payments from the EQIP between 2017 and 2022 for practices on the USDA's 2023 climate-smart list compared to the practices on its 2024 climate-smart list.

VIEW THE MAP

METHODOLOGY

EWG analyzed payment data from the USDA for fiscal years 2017 through 2022. We received the state- and county-level data from the USDA through public records requests and the national practice-level payment data via an email from a USDA employee, not as a response to our official request. The sums provided here represent payments made to farmers for each EQIP practice, not the amount committed to farmers for the practices, also known as obligations.

The state- and county-level EQIP data include only practices with more than four contracts in a state or county for a particular year. In response to EWG’s Freedom of Information Act requests, the USDA did not provide data for EQIP practices with four or fewer contracts in the state or county in a specific year, citing a privacy exemption. Because of this, the payments by county do not equal the total payments by practice for the state or nationally, and the payments by state will not equal the total payments nationally.

Many newly labeled USDA climate-smart conservation practices lack climate benefits

JUMP TO:

What climate-smart practices should do

New practices probably don’t benefit climate

New list creates alternate reality of robust climate funding

Climate money will now go to different states

Map: Environmental Quality Incentives Program payments, 2017-2022

Analysis methodology

OverviewNewly designated USDA climate-smart conservation practices likely don’t reduce agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Only practices that reduce emissions are eligible for $19.5 billion in 2022 Inflation Reduction Act funds.

The new designations make it look, erroneously, like a lot of money is going to climate-smart agriculture.

Against the backdrop of the deepening climate crisis, the Department of Agriculture recently added 15 Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, practices to its climate-smart conservation list – but many likely do little or nothing to help in the climate fight, a new EWG analysis of USDA data finds.

The new data is compiled in EWG’s just-updated Conservation Database. EQIP is one of the USDA’s largest conservation programs, helping farmers implement environmentally beneficial practices.

Some of the newly designated climate-smart practices already receive, by far, the most dollars from EQIP. So the revision of the list conveniently makes it look as though a large share of federal conservation funding will now go to climate-smart farming, providing a misleading picture of agriculture and climate in the U.S.

In 2022, EWG found that only a small portion of EQIP funding went to farmers’ implementation of climate-smart methods. The USDA's new list changes the equation significantly, effectively doubling climate-smart funding: Instead of 31 percent of EQIP funds subsidizing climate-smart farming between 2017 and 2022, it now appears that 63 percent did.

And the new climate-smart practices are about to get even more money, because they’re eligible to receive additional funds through the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA. This money totals about $19.5 billion, $8.45 billion of which is meant specifically for EQIP practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon in soil between fiscal years 2023 and 2026.

But many of the newly labeled practices likely do not have climate benefits. Eight of them are methods for irrigation and livestock management that likely don’t reduce emissions. One even increases emissions, according to USDA’s own data.

The USDA’s conservation agency, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS, says that in 2024 it will study the possible climate benefits of the newly added practices.

Until then, the USDA should remove them from its climate-smart list. No IRA funds should underwrite them without proof they actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate-smart conservation is intended to provide real climate benefits

For the past few years, the NRCS has made a list of practices funded through EQIP and the Conservation Stewardship Program, one of its other tentpole conservation programs, that it considers climate-smart. The practices on this list are intended to cause “quantifiable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and/or increases in carbon sequestration.”

In fiscal year 2023, the NRCS climate-smart list included 45 EQIP practices for which farmers received payments at some point between 2017 and 2022. (Other practices on the list didn’t get funding.) The funded practices included those with proven climate benefits, such as “cover crops,” “nutrient management” and “grassed waterways.”

In October 2023, the NRCS updated its list of climate-smart practices for fiscal year 2024. The roster now has 57 EQIP practices that received funding between 2017 and 2022, including 15 new additions (not including two practices that were removed). (See Table 1.) Only 14 of the 15 newly added practices got any funding between 2017 and 2022. “Soil carbon amendment” was added to the list for 2024 but didn’t receive any funds.

Table 1. 2024 climate-smart EQIP practices.*

EQIP practices added to USDA's 2024 climate-smart conservation list

EQIP practices removed from USDA's climate-smart conservation list for 2024

Brush Management

Wildlife Upland Habitat Management

Irrigation System, Sprinkler

Waste Storage Facility

Irrigation Pipeline

Waste Facility Cover

Irrigation System, Micro

Pumping Plant

Woody Residue Treatment

Windbreak/Shelterbelt Renovation

Herbaceous Weed Control

Prescribed Burning

Wildlife Habitat- Restore and Management

Fuel Break

Composting Facility

Feed Management

*List only includes 14 practices that received money between 2017 and 2023. It does not include “Soil carbon amendment,” which did not.

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

Many practices newly labeled climate-smart likely don’t benefit the climate

Of the 14 newly added (and funded) practices, more than half – eight – are irrigation or livestock practices, such as “waste storage facility” and “irrigation pipeline.”

The NRCS is calling all of these practices “provisionally” climate-smart – it cannot yet show whether they reduce emissions, so they have no proven climate benefits.

And “waste storage facility,” a structure that contains animal waste, increases greenhouse gas emissions, according to the data USDA does have.

These livestock practices are almost certainly not climate-smart. Agriculture contributes more than 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, with livestock a major source – particularly beef and dairy cattle, which emit vast quantities of methane.

EQIP funding to manage large amounts of livestock in concentrated facilities encourages farmers to keep relying on this model instead of raising animals on pasture, which could help to lower emissions.

Irrigation practices are also not clearly climate-smart. Although EQIP irrigation practices seem to enable more efficient water use, they do not always reduce total water use, especially in the West, where many farmers’ water rights follow “use it or lose it” policies.

In these cases, if a water rights holder does not use all their water allocation, they forfeit the rest, so they have an incentive to use the most they can. So installing more efficient irrigation wouldn’t necessarily save any water.

The IRA text says $8.45 billion of its funding should go only to EQIP practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon in soil – in other words, to the practices on the NRCS climate-smart list.

So calling the livestock and irrigation practices climate-smart, provisionally or not, is problematic, since the IRA states that its agricultural funding should go to conservation practices that reduce emissions or sequester carbon.

The NRCS has said it will study provisional practices in 2024 to measure their greenhouse gas emission reductions, if any. It has also said if it does not find benefits, it may remove the provisional practices from the climate-smart list for the following year.

But history would show that these practices may not be studied in 2024: All eight provisional practices on the 2023 list remain on the list for 2024 – and all are still listed as provisional.

New list creates alternate reality where lots of money has gone to climate-smart farming

Some of the practices just added to the 2024 climate-smart list received the most EQIP funding between 2017 and 2022 – painting an inaccurate picture of a lot of money going to practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But because many of these new provisional practices likely do not reduce emissions, only a small share of EQIP spending is actually going to practices with proven climate benefits.

EQIP sent $5.5 billion to farmers across all practices between 2017 and 2022. Only $1.7 billion of this, or 31 percent, went to practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, most of which have been proven to reduce emissions or sequester carbon in soil.

But with the addition of the 14 funded provisional practices for 2024, that amount more than doubled to $3.47 billion – or 63 percent of all EQIP spending.

That’s because many of the practices added to the 2024 list are the most-funded practices in the whole program. The 10 practices with the most total EQIP payments made up $2.65 billion between 2017 and 2022 – almost half of all EQIP spending. Only two of these, “cover crops” and “forest stand improvement,” were on the 2023 climate-smart list.

But when the list was revised for 2024, eight of the 10 practices with the most program funding appeared on it. In addition to the two from 2023, these included “brush management”; “irrigation system – sprinkler”; “waste storage facility”; “irrigation pipeline”; “waste facility cover”; and “irrigation system – micro irrigation.” (See Table 2.) Five of these six practices are livestock or irrigation practices.

Of the 10 practices with the most EQIP payments, the only two not on the 2024 climate-smart list were “fence” and “pipeline,” which brings water to livestock or wildlife.

Table 2. Almost all the 10 EQIP practices with the most payments between 2017 and 2022 were added to the 2024 climate-smart practice list.

Practice rank

Practice name

EQIP payments 2017-2022

Percent of all EQIP payments

On 2023 climate-smart list?

On 2024 climate-smart list?

1

Cover Crop

$504,812,892

2

Brush Management

$314,991,152

3

Irrigation System, Sprinkler

$313,561,007

4

Fence

$311,036,533

5

Waste Storage Facility

$252,142,865

6

Irrigation Pipeline

$230,101,825

7

Waste Facility Cover

$228,568,531

8

Irrigation System, Micro

$175,194,972

9

Pipeline

$162,365,526

10

Forest Stand Improvement

$159,735,684

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

Addition of provisional practices to climate-smart list changes states receiving IRA funds

Expanding the climate-smart list will also change where the IRA money goes.

Across EQIP, payments are concentrated in just a few places – 44 percent of the money spent between 2017 and 2022 went to just 10 states. Similarly, 45 percent of payments to practices on the 2023 climate-smart list went to farmers in just 10 states, and 46 percent of payments to practices on the 2024 list went to farmers in the 10 states with the most payments.

When the list changed, so did the states that got the most climate-smart money. California and Texas were the top two on both lists, but the others changed drastically.

Seven of the top 10 states on the 2023 list were located in the Mississippi River Critical Conservation Area, a region of the country with important agricultural, industry, wildlife and ecological resources. But only four of the top 10 states on the 2024 climate-smart list were located in the conservation area (Table 3). Now Southern and Western states like Colorado, Georgia and Oregon will receive more so-called climate-smart funding.

Table 3. The 10 states that received the most payments between 2017 and 2022 for practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, compared to those on the 2024 list.

State rank States with the most payments for 2023 list Payments 2017-2022 for practices on 2023 list States with the most payments for 2024 list Payments 2017-2022 for practices on 2024 list

1 California $167,970,025 Texas $371,894,245

2 Texas $99,642,015 California $359,871,676

3 Missouri $69,273,408 Georgia $137,069,838

4 Indiana $65,270,184 Colorado $118,425,439

5 Tennessee $64,641,082 Arkansas $110,504,198

6 Wisconsin $57,753,631 Mississippi $100,305,742

7 Iowa $55,750,215 Oregon $93,274,547

8 Ohio $55,410,931 Oklahoma $91,351,469

9 Oklahoma $55,025,391 Indiana $91,034,785

10 Mississippi $54,055,521 Ohio $90,089,372

Total 10 states $744,792,403 Total top 10 states $1,563,821,311

Source: EWG, from public records requests for USDA-NRCS program data.

The map below shows which states received the most money for practices on the 2023 climate-smart list, compared to those that got the most money for practices on the 2024 list.

INTERACTIVE MAP

Environmental Quality Incentives Program payments

This application provides details about payments from the EQIP between 2017 and 2022 for practices on the USDA's 2023 climate-smart list compared to the practices on its 2024 climate-smart list.

VIEW THE MAP

METHODOLOGY

EWG analyzed payment data from the USDA for fiscal years 2017 through 2022. We received the state- and county-level data from the USDA through public records requests and the national practice-level payment data via an email from a USDA employee, not as a response to our official request. The sums provided here represent payments made to farmers for each EQIP practice, not the amount committed to farmers for the practices, also known as obligations.

The state- and county-level EQIP data include only practices with more than four contracts in a state or county for a particular year. In response to EWG’s Freedom of Information Act requests, the USDA did not provide data for EQIP practices with four or fewer contracts in the state or county in a specific year, citing a privacy exemption. Because of this, the payments by county do not equal the total payments by practice for the state or nationally, and the payments by state will not equal the total payments nationally.

No comments:

Post a Comment